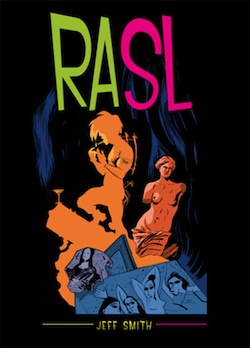

RASL, released by Cartoon Books in late September, is the complete one-volume collection of Jeff Smith’s most recent project, which initially ran in single issue comics from 2008 to 2012. Smith is renowned for the long-running series Bone, winner of several Eisner Awards, which ended in 2004—but this is a rather different sort of story. RASL is best described as a scifi noir, and it follows a parallel-universe hopping art thief/ex-military engineer (whose tag is the titular anagram, “RASL”) through his trials and tribulations.

RASL presents an obvious shift in tone and subject matter for Smith, whose books are generally kid-friendly. The protagonist, Rasl, has a violent streak, drinks far too much in order to deal with the side effects of universe-hopping in the Drift, and has several “on-screen” sexual relationships with different women; the plot is concerned with physics, the military-industrial complex, and a general theme of personal responsibility for complex problems. So, not the usual fare.

I’d like to start with the positives: namely, the science fictional plot premised around Nikola Tesla’s “lost” journals and the related story of Rasl’s initial research and its consequences. The most powerful moments in the text, I would argue, are the reveal of the Navy ship that lost correct energy phasing during a WWII-era test of Tesla’s energy technology—and the reveal, at the climax, of what the new St. George Array had done to a small town outside of the project’s airspace. The narrative tension Smith cranks up as we move closer and closer to finding out the nature of the grand awful truth is great; the intimate and personal view of it that Rasl—who is partially responsible—gives the reader is even better.

At its strongest, RASL provides tense emotional moments and a sense of great danger in the multiple-universe that we inhabit, a danger that comes primarily from other people. Additionally, the prose is tight, the art is handsome and often the right kind of jarring, and the story comes together cohesively. I found myself quite caught up in the slow reveal of the technological dangers of the array. Also, the characterization of Tesla throughout is a delight—he’s complex, a bit sad, that sort of thing. But the really clever bit is that all that we’re told here about him is colored by the brush of a man who once idolized him, the protagonist; that’s an intriguing dimension of shading on the history.

Unfortunately, RASL also has distinct problems in the form of its cast of woman characters and the roles they’re given to play—one that I couldn’t ignore despite a fun plot and beautiful art. Smith is certainly a big talent and this isn’t a “bad” graphic novel by any stretch of the imagination. But, in the end, I was disappointed, and probably moreso because of how good the rest of the book was. I expected better, and I assure you, I did my best to read generously and with an eye to the fact that maybe these seemingly sexist, problematic characters were supposed to be—ironic? Commentary?—but couldn’t come down positively in the end.

We have two primary women: Annie and Maya. Annie is a sex worker with whom Rasl has relations; she’s murdered early on, and he starts finding different versions of her in the multiverse to sleep with, trying to rescue one (from also being murdered to punish him). The other, Maya, was the wife of his best friend and also a scientist—though we only see her romantically, never as much of a scientist—who turns out to be a stone-cold killer/seductress/liar of the type so familiar to noir. To recap: two women. One is a sex worker who exists in the story to be murdered as motivation; the other ends up being a walking monument to the “evil bitch” trope, who is killed by Rasl in the end after he outsmarts her.

There are also other women, like the government suit—who is killed pretty nastily, in a way that seems almost entirely designed to undermine the sense of authority we might have gotten from her previously. And there are some unnamed strippers, one of whom comes onto Rasl and who he has to let down gently with a handful of money, because he’s that kind of guy. The only remotely non-sexualized “woman” character is the silent, deformed child-ghost-thing that tries to give Rasl clues throughout. She’s entirely voiceless, and is also shot a few times in the head, though she just keeps rematerializing.

So, that. That’s a problem—and a thoroughly avoidable one. The text even gestures briefly toward a deeper understanding of the problems in how Rasl relates to Annie, how he uses her without seeing her, but never quite goes there and ends up still using her as a stock type (and a particularly fucked up stock type, at that). I understand the idea of writing a noir. I also understand that it is possible to have a woman who’s the antagonist, who’s evil, without going the whole “no characterization, really, beyond her being a probably-sociopathic sexpot manipulator” route. It’s that these tropes are used without depth, in a text that certainly had the room and opportunity to develop them outside of the problematic boxes that they are.

So, in some measure, I did enjoy RASL. I was left, however, with a bad taste in my mouth. The gender politics of the text are true to the noir roots, perhaps, but that doesn’t make them pleasant to wade through. While I suspect that many readers will breeze through without a pause, I also expect that others will find themselves as distracted from the plot as I was by the tropes that seem to structure each woman character in the story—tropes that stand in place of personalities or character development, for the most part. Rasl himself shares some of the generic backgrounding of the text—the drinking, the deep emotional pain, the disaffection—but he is also allowed a unique backstory and driving action in the narrative.

The women, not so. They are primarily their tropes. And that, despite how good the rest of the book might be, was a disappointment.

RASL is available now from Cartoon Books

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.