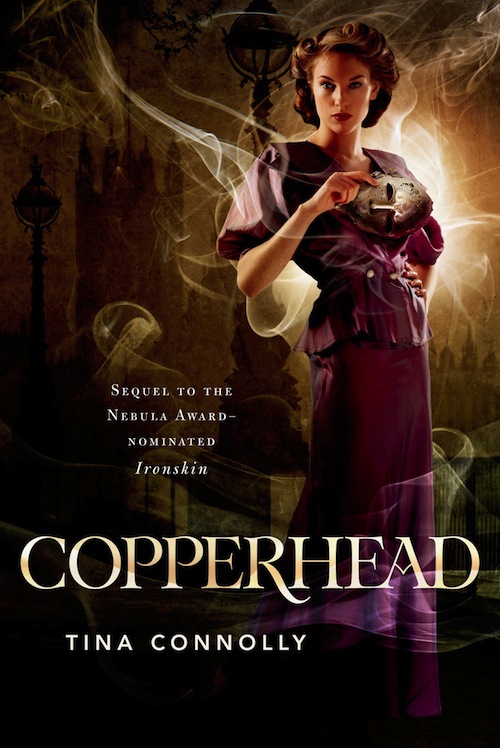

Check our Copperhead, the second novel in Tina Connolly’s historical fantasy series, Ironskin. Copperhead is available October 15th from Tor Books!

Six months ago, Helen Huntingdon’s sister Jane uncovered a fey plot to take over the city. Too late for Helen, who opted for fey beauty—and now has to cover her face with iron so she won’t be taken over, her personality erased by the bodiless fey.

Not that Helen would mind that some days. Stuck in a marriage with the wealthy and controlling Alistair, she lives at the edges of her life, secretly helping Jane remove the dangerous fey beauty from the wealthy society women who paid for it. But when the chancy procedure turns deadly, Jane goes missing—and is implicated in a murder…

It was pitch dark now, except for the faint glow of the eerie blue mist. Helen strode down the cold empty street, intensely aware of her bare face. She started every time she thought she saw a quiver from the mist.

Where was Jane living now?

Jane had lived with them for a couple months earlier in the year, helping Helen to convalesce from the fey attack. Jane had often taken the train down to the country to see her fiancé Edward Rochart and his daughter Dorie. But as the grey summer continued, the blue bits of fey started appearing— little by little, settling over the city. Alistair’s gang turned from horses and dice to secret meetings where they plotted to rid the world of anything inhuman—dwarvven and fey.

Helen had not paid it much attention at first, assuming there was more drinking than politicking going on. But Jane did, and Jane was becoming more and more visible, agitating to fix the faces of the beautiful women. Beautiful women who refused to give up their dangerous beauty. Husbands who, though supposedly anti-fey, were not quite as quick to sign off on their wives returning to their old faces. It sometimes reminded Helen of that old fey story about the knight told to choose whether his wife should be beautiful at day and ugly at night, or vice versa. It was clear what these men were choosing.

To be fair, it wasn’t just the men. Helen had actually heard that fake masks were popping up at dances around the city. Not at the very best houses, mind you, but down a rung or two. For the price of some iron, you could pretend that you were a dazzling beauty underneath. Tempt some bachelor with the promise of what he might find, safe inside his home, once he carried you over that iron threshold…

Oh, Jane would never believe that one. Helen could just imagine her vitriol now. She sighed. Stubborn Jane did not see that you simply had to let these men, men like Alistair and Grimsby, have their own way. There was no arguing with obstinate fools. Not to mention that Jane’s temper (never good in the old days) had gotten on edge after her fiancé had gone into the woods with his fey-touched daughter—Helen didn’t know exactly why, as Jane called the decision foolish and pig-headed and refused to discuss it. Jane stopped returning to the country, and therefore spent more and more time at Helen and Alistair’s house. Which resulted in a violent quarrel between Jane and Alistair that ended with Jane stalking out to find some terrible shack to live in and Alistair threatening to hurl her ironskin self from the door if she came through it again.

Helen realized she was paused on the street corner close to the trolley stop, staring at a shop completely covered in blue. Early on, the city had tried paying poor folks to scrape blue off of walls and streets. But the fey had seemed to organize and retaliate—targeting only the cleaners, until at last the mounting number of deaths had caused the city to abandon that plan. Her fingers clenched around the handles of Jane’s carpetbag as she stood there in the biting cold. There had been a bakery there, before. But the bits of fey kept coming and coming, like ivy climbing the walls, choking the windows and doors. The owners had tried everything. Finally they moved out. She thought she had heard they decamped to some relatives in the country—ironic, when all the fey once came from there.

After the owners left, the mists of fey just got worse and worse, till no one would walk up to that shop for love or money. The mist thickened. Bulged.

But she had never realized that it sort of thrummed before.

Or that the tendrils coming off the house came so close to the sidewalk.

Helen’s heart jolted, beat a wild rhythm, flooded her body with the command to run.

No, the house had not been like that before.

The mists were moving. Toward her.

The interwoven bits of fey flowed from the store, creeping toward her across the front walk, all of that thick deadly blue coming at her like a slow-building wave.

Helen ran.

She pelted down the street, breath white in the cold, eyes watering from the November wind. The carpetbag beat a lumpy rhythm against her side and still she ran, not looking back, down and around the corner until she got to the trolley station where, wonder of wonders, a trolley was just preparing to depart. She flung herself through the closing doors and it pulled away.

She moved to the window, looked out between the pasted-up notices and garish advertisements to see if she saw a blue wave tearing down the street after them. But she saw nothing more than the familiar thin scarves of blue that dotted the houses and shops and streets.

Her breath fogged the glass and her face came back into focus, white and strained, mouth dark and breathing fast.

Good night, she looked a mess.

Helen sat down in an empty seat with the carpetbag firmly on her knees, still breathing hard, and attempted to smooth her hair. Slowly she adjusted her skirts, straightened the silk jacket of her dress where it had twisted around her waist, felt her heartbeat slow. A weary ticket-taker moved down the aisle, stuck a hand out for her pence without inquiring into her distress.

She had only rarely been on the trolley, and never this late at night before. It had been down for most of the war—all the fey trade had ceased at the beginning of the war, and everyone had quickly run out of those fey bluepacks that used to power everything so cleanly. Tech had come lurching back in a number of different directions at once, as humans tried to make up for the missing energy. The electric trolley had been one of the big civic pushes to get going again—but that did not mean that everyone rode it equally. Men outnumbered women, but a few women did ride it. The working poor, in old-fashioned layers of skirts, headed home to the factory slums from some slightly better position elsewhere. Reformers like Jane, in trim suits or even slacks, working for their pet causes: women’s votes or dwarvven accessibility or some equally tedious thing. Women in silk dresses, no matter how civic-minded they were, did not ride the trolley. Helen wrapped her dark coat more tightly around the plum silk, as if that would help her blend in.

The passengers were the one thing Helen liked about the trolley. Despite the fact that they made it cramped and smelly, they were also interesting, because people were interesting. She had always liked people—but now with the fey mask her interest in people seemed even more pronounced.

People…

Helen realized with a jolt that all the men in the trolley were staring at her, whether openly or surreptitiously.

She had no iron mask.

She suddenly felt naked. The iron mask was not just protection from the fey. It was protection from herself. It was protection from her own fey charm affecting everyone around her. She had gotten used to the mask turning it off, but now it was on in full force.

Now she was vulnerable.

“Do you have the time, miss?” It was a young man, fishing for an opportunity to speak to her. You should never engage any of them, she knew, but she always felt a sort of kinship for the young ones. She knew what it was to want.

“I’m sorry, no,” said Helen. In the old days it had taken more than a smile to make a man blush, but now with the fey glamour every moment of charisma was magnified, and he went bright red to the ears, though he pretended not to.

“Does she look like she’d carry a watch?” said another man, rougher. “No place to keep it in that getup.”

Her coat was hardly revealing, unless he meant her legs. She was not going to inquire what he meant.

With effort she pulled the carpetbag onto her lap and started to go through it for something to do, some way to pointedly ignore the riders around her.

Surely among everything else the ever-alert Jane had some iron in here, something Helen could use to defend herself from fey. She opened the clasp and peered into the bag’s dark contents.

The trolley was dim and the inside of the carpetbag greyblack. Helen poked around the rough interior, trying to feel things out without exposing them to the gaze of the other passengers. That tied-up roll of felt, there—those were the tools Jane used for the facelift. Helen did not remember putting them in the bag, but she must have done it in her shock.

In a pocket compartment was a sloshy bag of clay in water. A larger compartment held a rough wooden box, secured in place. She would have to pull it out to discover what was inside. She rummaged around the main compartment, found a scarf and hairpins. A small leather-bound book. Train-ticket stubs.

Apparently not everything in here pertained to Jane’s secret work.

At the very bottom Helen found some of that ironcloth that Jane used to help her focus the fey power. Helen had tried it, but so far she had not gotten the hang of it. Jane used the combination of the iron plus the fey to direct the bit of fey she still wore on her face—give her the power to put Millicent into the fey trance, for example. Late one night Jane had confided to Helen that she had actually used the fey power to make someone do her bidding once—but that it had scared her enough that she never intended to do it again.

Perhaps the cloth would substitute for the iron mask that Alistair had taken; perhaps Helen could use it as protection. She pulled the cloth out to examine it, and her hand knocked against a small glass jar. Tam’s bugs. She must have put them in the carpetbag as she left the house.

Helen did not particularly like bugs, but her hand closed on the jar and she smiled wistfully, remembering Tam. The poor boy—mother gone, now stepmamma, left alone with that horrible man and his horrible friends. Should she have tried to take him with her? But how could she, when his father was right there? She did not know what you could do for a case like that.

Just then the trolley came to a jerking stop, throwing folks who were standing off balance. A very short elderly woman stumbled near Helen, her bag tumbling to the ground. Helen jumped to retrieve it and helped the woman to sit on the bench next to her, half-listening to the litany of complaints rising from all sides.

“How can I keep my night shift when—”

“Boss makes me punch in—”

“Docked pay—”

“Fey on the tracks,” one said knowledgeably, though that didn’t seem likely. The blue mist shied away from iron.

“Are you all right?” said Helen. The old woman had not quite let go of her arm, though it was likely she was finding the bench difficult as her feet did not touch the floor.

The woman’s fingers tightened and Helen looked up to find the bored ticket-taker staring down at them, his face now purple with indignation.

“Your kind isn’t to be here,” he spat at the old woman. “Back of the trolley.”

Helen looked to the very back of the trolley. She saw a cluster of very short men and women there, bracing themselves against the wall for balance. The trolley straps dangled high over their heads.

The dwarvven.

The woman’s wrinkled chin jutted out. No one from the back was running to her aid—though the dwarvven were said to be stubborn, fighting folk, these men and women looked tired and worn-out. Ready to be home.

“C’mon, dwarf,” the ticket-taker said. Dwarf had not been a slur once, but it was quickly becoming one under Copperhead’s influence. It was the way they said it. The way they refused to attempt the word the dwarvven themselves used.

Helen placed her hand on top of the woman’s wrinkled one. “This is my grandmother,” she said pleasantly to the ticket-taker. Confidentially, leaning forward, “Poor nutrition in her youth, poor thing, combined with a bad case of scoliosis. Oh, I expect by the time I’m her age I’ll be no higher than my knees are now.” She ran her fingers up her stockings to her knees, pushing aside the plum silk, and gave him a nice view of her legs in their bronze heels. “Can’t you just imagine?”

The ticket-taker looked a little glazed by the flow of words and by the legs.

Helen dropped her skirt and said, “Thank you so kindly for checking up on us. I feel so much safer now. We won’t take up any more of your time.”

With a lurch the trolley started again. Dazed, the ticket-taker stumbled on, and the dwarvven woman’s fingers relaxed on Helen’s arm. She pulled her knitting from her bag and began to focus on the flying needles. But under her breath the woman said softly, “I owe you,” to Helen.

Helen patted the woman’s arm, watching the wicked points of the needles fly. “Don’t be silly, Grandmother.”

Helen turned back to Jane’s carpetbag, grinning inwardly. She rather thought the dwarvven woman would be just fine on her own, now that she had those weapons in her hand again.

But the flash of legs had attracted the attention she’d been trying to avoid.

The boor nudged the young man who had asked about the time. “Ask her to the dance hall with ya. Pretty silky thing like that, even if she is stuck up.”

Helen flicked a glance over at the two men, assessing the need to be wary. She had encountered rough characters at the ten-pence dance hall back in the day. But she had always had a knack for finding protectors. Their loose, dark button-shirts and slacks said working men—the young man, at least, was well-groomed and nicely buttoned, which spoke better for his intentions. She smiled kindly at the young man and had the satisfaction of watching him scoot away from the drunkard, trying to stay in her good graces.

“Too good for us, she thinks,” said the boor. “I could tell her a thing or two about that.”

Several seats down she caught an amused expression. A man had carved out a spot for himself on the crowded trolley by crouching lightly on the back of one of the seats, hovering over rougher, sturdier looking fellows. A fresh notice pasted behind him read: Your eyes are our eyes! Alert the conductor to suspicious persons. His face looked familiar, but she could not think why at first. He had a lean, graceful look, like the dancers she and Alistair had seen at the theatre last spring, before he started spending all his evenings with those terrible friends of his. Helen thought she had seen this man recently, exchanged a smile with him—that was it, wasn’t it? He looked like—or was—the man from the meeting tonight, who had perched on the windowsill during the demonstration. Everything prior to the disaster seemed to have vanished from her head. She looked more closely. The man was on the slight side, but all slim muscle and amused mouth. Amused at her expense—watching her try to cope with the boor. Helen was perfectly capable of defending herself through wit at a party—but what good would it do you with a sloshed village idiot like this?

Well, she’d have to say something, or be on edge for the rest of the trip. Helen turned to face the boor, who was still making comments under his breath. Her mind raced through what she could say to tactfully make him stop. Was there anything?

“Like the story a sweet Moll Abalone,” said the boor, “who thought she was a lady fine, but when she found she could make her way by not being a lady… whoo boy! Just think on that, girlie. Oh cockles and mussels alive, alive-o…”

The lithe man raised amused eyebrows at Helen and Helen’s temper lit like a match touched to dry kindling. She unscrewed the bug jar she held and dumped the entire contents on the drunken boor’s head. Bugs and grass rained down around him, and his jaw fell slack in shock.

So did Helen’s, for she had not entirely meant to do that. What on earth came over her sometimes? It was as if she had no willpower at all.

The young man opposite laughed delightedly. “You show him, miss,” he said. “More than a pretty face, aren’t you?” and several others clapped.

Helen’s grin faded as quickly as it had come, as the drunken boor lurched from his seat, more quickly than she would have guessed. Crickets fell from his shoulders and suddenly the hot blast of whiskey was in her face, the rough red-pored face close and hot. In his hand was a knife.

She had no time to do more than register the danger and suddenly the man was gone, shoved away. The lithe man stood between them, his back to her. He was wearing some sort of dark leather jacket over slim trousers, made from a tough woven material. It was all very close-fitting, and free of loops and pockets and things that would catch. It was an outfit made for getting away from something. “Here now,” he said softly, dangerously, and then his voice dropped even lower, and despite the absolute stillness of the fascinated trolley car Helen could not hear what he said into the man’s ear. It was something, though, for Helen could see one of the boor’s outstretched hands, and it shook, and then he drunkenly backed up a pace, then another, then another, then turned and pushed his way through protesting bodies toward the other end of the trolley.

Despite her relief, she had had experience with rescuers. Rescuing a woman was helpful, kind—but generally also an excuse on the rescuer’s part to talk to her. She appreciated his audacity, but that sort of fellow was always harder to tactfully get rid of. Telling them you were married didn’t always stop them.

And she worried that this one had followed her. How could they have coincidentally ended up on the same trolley? Was he interested in her, or did he have another, more dangerous motive for turning up twice in her life to night?

Helen turned back from watching the boor go, pasting a pleasant smile of thanks on her face, ready to parse the man’s motives, feel him out.

But he was gone. The folks around her were watching the drunkard leave. The dwarvven grandmother had her knitting needles thrust outward, watching the boor leave with a fierce expression on her face. The mysterious man must have taken the opportunity to vanish in the other direction, into the crush of bodies. Helen felt oddly put out.