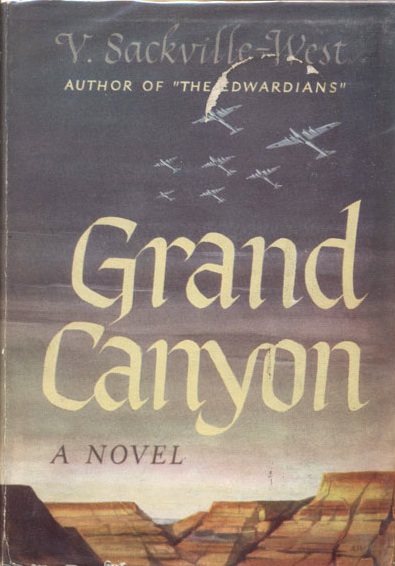

A curious alternate future (written during WWII), take a look at Vita Sackville-West’s Grand Canyon, out now in ebook format:

The Second World War has been won. Germany has conquered Britain and all of Europe, and now only America stands, protected for now by the Pacific Charter – a precarious promise of peace from the Reich.

Lester Dale and Helen Temple, two strangers united by their memories of a lost England, are staying in the Grand Canyon Hotel in Arizona amongst a variety of displaced Europeans and naive American youths. When the fragile peace eventually shatters, only Lester and Helen can take charge, and lead their fellow guests into an uncertain future.

Filled with extraordinary characters and strange twists, Grand Canyon, written during World War Two, is Vita Sackville-West’s unflinching exploration of what might be, and a warning of the dangers of compromise when world peace is at stake.

[Read more]

The dining-saloon filled up with people and chatter as the hour for feeding approached. The animals must be fed. Animals in the Grand Canyon Zoo couldn’t be allowed to go hungry. The hotel was doing well; never since its inception had it enjoyed such a season as this, when the published announcement of the manœuvres attracted holiday-makers from all parts of the continent as well as the faithful habitués and the unusual come-and-go of soldiers old and young who, bored with living in tents in the constant company of their mess-mates, sought distraction by straying into the hotel for cocktails and then remaining for dinner. The hotel, in fact, scarcely knew how to cope with all the people wanting to use it. Its resources were strained; the employés had never anticipated such a demand; they got flustered, ran about unnecessarily, lost their heads when visitors strolled up to the reception bureau asking questions, tried to remain polite and helpful according to the tradition in which they had been trained. (“Never let a guest see that you think him a nuisance; that you are at a loss for a reply; that you cannot furnish the information required; that you are tired, irritable, overworked; that there are other guests who need attention and who are waiting their turn; remember that guests are always impatient, never patient; that they all think they pay enough for their money to buy politeness and immediate competent service; keep your head, satisfy everyone, be amiable, helpful, sympathetic; never show that you have any human feelings or failings at all.”) Hard demands were now made on them; demands which had never been made on their first engagement. On their first engagement they had merely been told that they should serve in the Grand Canyon hotel, an ordinary hotel service in an extraordinary place; but the extraordinary place didn’t affect them, since one hotel was very much the same as another hotel wherever it was, and they didn’t take much notice of the canyon outside. Taking service in an hotel meant taking service in an hotel, and that was that. It meant the usual routine and the usual things one had been trained to do. Just an hotel, a tiny world sporadically invaded and inhabited by strangers, come to-day and gone to-morrow, strangers who had to be treated with deference, however much one liked or disliked them. Cooks must cook; waitresses wait; managers manage; porters be portative; the reception bureau be receptive. All must be amiable, welcoming, helpful. Merciful Mother of God, what a task.

The only person who seemed completely unshaken was the Manager. He seemed to be enjoying himself, a happy cork bobbing on the waves of this sudden excessive business. He was here, he was there, he popped up everywhere he was wanted. He bobbed and popped. He was at the bureau, at the cocktail bar, in the lounge, in the kitchen. A deft touch, leaving everyone soothed and satisfied. A man of genius in his own way. He had the required touch of tact. He soothed the guests, he soothed the staff, he soothed the central management from New York whenever they got hold of him over the telephone. He always knew the right word to say. Whenever his central management got him on a long-distance call, he was able to convince them quietly that he was quite able to deal with the rush of business due to people arriving at that lone outpost the Grand Canyon Hotel in Arizona where the forces of the United States were concentrating for their manœuvres.

The central management was a nuisance to him with their long-distance calls. Why could they not trust him to manage things locally for them, without bothering a man perpetually, interrupting him even while he was eating his dinner? He was working hard enough for them from morning to night, and working sideways for his own purposes too, a full-time job for any man; it was not fair to interrupt a man sitting down to snatch a mouthful of mutton at the very moment he expected to have a moment to himself and to be able to think about a man’s personal life. It was hard to be perpetually on tap; never to be able to shut himself into his little office behind the bureau and give orders that he was not to be disturbed. Not even half an hour to himself for a nap. Always ready to emerge smiling, when the discreet tap came on his door from his clerk and a whisper informed him that Mister or Missis or Miss Blank was waiting to speak to him. Inwardly hurling the mister, missis, or miss to the bottom of the canyon, he must emerge bland, urbane. “Now just what can I do for you, sir, madame?” Be of service; always be of service. You had a toothache, had you? Pooh. Managers don’t have toothaches.

So he smiled. As he had a squashed-up face, triangular, rather Mongolian, rather like a cat, he could smile effectively. His face broadened out sideways as he smiled. It was not a pleasant smile, for those who could notice; it suggested that he would knife you in the back for a buck or even for the sheer pleasure of doing it; but fortunately for his flock of guests few people did notice. To most of them he was just a smile poised above a black morning-coat, with pin-stripe trousers. The Manager was very particular about the correctness of his clothes. His predecessor had sloped round in corduroy slacks and a khaki shirt open at the neck; the new manager had altered all that. He believed in local colour and exploited it freely, but he also believed in the metropolitan touch for himself and his reception clerk. They were the only black-coats in the hotel and he had contrived to persuade the central management that it paid. Let everybody else be as picturesque as you like; let them go about in fancy dress, those dude-ranch boys; encourage them, indeed, to do so; but let the reception bureau suggest the Waldorf-Astoria. He believed in the value of contrast. He was an artist after his own fashion.

That was why he called his clients sir or madame, instead of by their names in the friendly familiar American way. It gave a touch of old London; a touch of old Paris; it startled them, made them notice him. It was deliberate. Everything he did was deliberate.

This time it was Mrs. Temple waiting to speak to him. He did not like Mrs. Temple, knowing that he failed to impress her. He noted, however, that she wore one of his poinsettias pinned against her shoulder. It had been clever of him to arrange for those poinsettias to come up from Mexico; little surprises like that amused the guests, and he usually managed to provide at least one surprise a day. Besides he had been glad of the opportunity to exchange a few quiet words with the man from Mexico. The poinsettias had given him a good excuse.

Mrs. Temple wanted to know if a note awaited her.

The Manager, swirling neatly on his heel, whisked it out of her pigeon-hole and flicked it down on the desk before her with the air of one who deals out the fourth ace. The trim little typed envelope caught his attention, and although Mrs. Temple was not a person at whom one winked he permitted himself a slight raising of the eyebrows accompanied by a slight jerk of the thumb over his shoulder in the direction of the Painted Desert. It all indicated very subtly and respectfully that he and Mrs. Temple might be sharing an innocent secret. Mrs. Temple did not respond. Too much of the English lady, he thought, stung to vexation; too much of the English lady to share a joke however innocent with an American manager. He put down another mark against Mrs. Temple’s name. She had snubbed him again.

Still he could not stop himself from admiring what he called her poise as she crossed the lounge on her way towards the dining-saloon. She had a manner about her, that woman; a grand manner. She was different from the other tourists whom he despised.

A cheerful noise was coming from the dining-saloon. In a few moments he must make his appearance there, stopping at each table, bending down to enquire whether everyone was perfectly satisfied. Nothing would have induced him to neglect this piece of routine. But that could wait for a little, until the diners were further under way. He had found by experience that a man is better disposed half way through his dinner than at the beginning of it, and although he was always prepared to rectify complaints he preferred to avoid receiving them. Meanwhile, very well contented with himself, he remained standing behind his bureau, delicately propping himself by the tips of his fingers on the polished surface, swaying slightly on his toes, and permitted himself the luxury of surveying the empty lounge. Quite soon, he knew, his two bell-hops would come running in to their evening task of putting everything tidy, shaking up the cushions, pulling the chairs into position, emptying the ash-trays, taking away the cocktail glasses (and, he suspected, finishing off the dregs as soon as they got out of the room. He must see to that). Their arrival would be the signal for his own progress into the dining-saloon, but such was the precision and severity of his organization that they would not arrive an instant before the appointed hour. He could count on having the lounge to himself for another five minutes. He was pleased with the lounge. It was his creation, a very different affair from the ramshackle hall he had taken over from his predecessor. He had persuaded a sum of money out of the central management and had expended it in the furnishings and decorations he judged best suited to the expectation of his guests. Very full of local colour it was. Navajo blankets lay on the floor, Mexican serapes were flung carelessly over the armchairs. (He had hesitated for some time between these and some very modernistic Fifth Avenue chintzes.) The effect, he thought, was colourful. Shelves ranged with Hopi pottery ran round the walls. The waste-paper baskets were of the plaited Papago make. The mats under the cocktail glasses were Pima make. Similar objects were purchasable by the souvenir-minded tourist at the Indian shop opposite, but the tourist was advised to come to the Manager’s office first to be told exactly how to proceed. He would be invited into the office as a special favour and in a locked-door condition of secrecy would be told how very difficult it was to get the Indians to sell their wares at any price; Indians were queer people; nobody could understand them unless they had lived amongst them for years and then not even then; the queerest things happened amongst Indians; they twirled sticks to make a noise like falling rain; they used the yucca fibre to make their baskets; they used the agave leaves and the reed and a rush which grows by the Gila River; for their pottery, they used vessels of clay mixed with cedar bark or corn-husks; they danced seasonal dances which no white man or woman might see.

The Manager knew nothing about any of these things, but he contrived to put up quite a good show of pretence when his tourists came into his room behind the scenes. Above all, he knew how to stimulate custom for the shop opposite. He had become quite glib about the Indians, and their legends. In the very first week of his appointment he had recognized them as Local Colour. After two years of his job at the canyon he had learnt how to exploit the material he had at hand. He exploited it perfectly. He had mugged up all the necessary information and could now put it across without making a single blunder.

He had taped his clientele.

Leaning his finger-tips on the bureau he wondered whether he might not now ask the central management for a rise of salary.

On the whole he was pleased with life.

The only thing that bothered him, the seed in his tooth, was the uncertainty of the moment when his instructions would arrive. Every time the telephone shrilled, he lifted the receiver in a cold anticipation of hearing the prearranged code phrase: “We hope you are finding the new bathroom installation satisfactory,” the distant voice would say. “Perfectly satisfactory, O.K.” he would have to reply, and then he would replace the receiver and hurry off to set the hotel on fire. His dear hotel, his pet, his creation, his pride, his triumph. He would have to sacrifice it all to the Cause; he would have to see his Local Colour going up into flames. The Manager was a man torn in half. One half of him wanted to advance the Nazi cause; the supreme domination of Germany over the world; the other half wanted to keep his creation intact since he had made it and felt about it as a mother feels about her child; it was his child, and he felt a savage sense of possession; but, committed as he was to the Nazi bribery, he had to destroy the very thing he loved, a hard thing for any man to do, so no wonder that he struck harshly at Sadie when he saw her coming out from the dining-saloon. He vented on her the worry that was in his heart, an oblique relief of ill-temper such as we all indulge in when something else goes wrong.

He did not like Sadie from any point of view; he found her physically repellent with her meagre body unsatisfying to a man of his tastes; he deplored her ill-health, and was irritated by the solicitude she evoked in Mrs. Temple. Sadie was over-worked; Mrs. Temple thought so and said so. The Manager of course agreed and would see what could be done about it; then as soon as Mrs. Temple’s back was turned he would invent some unnecessary extra job for the girl to perform. And now …

“Sadie! What you doing here at this time of day?”

She withdrew her handkerchief an inch from her lips to answer in a whisper, “I’ll be down again in a moment.”

“Can’t hear what you say. Speak up, can’t you?”

“You heard me. D’you want to make me cough?”

“Oh, if that’s it.… Not shamming, are you?”

She silently showed him the handkerchief, stained with blood.

“Ugh, take it away. And take yourself away, disgracing the hotel; visitors don’t like squalors like you. Come back as soon as you get yourself presentable again. There’ll be a lot of folk in to-night and plenty to do for all. Be off with you,” he added sharply, hearing voices and laughter just outside.

Grand Canyon © Vita Sackville-West 2012