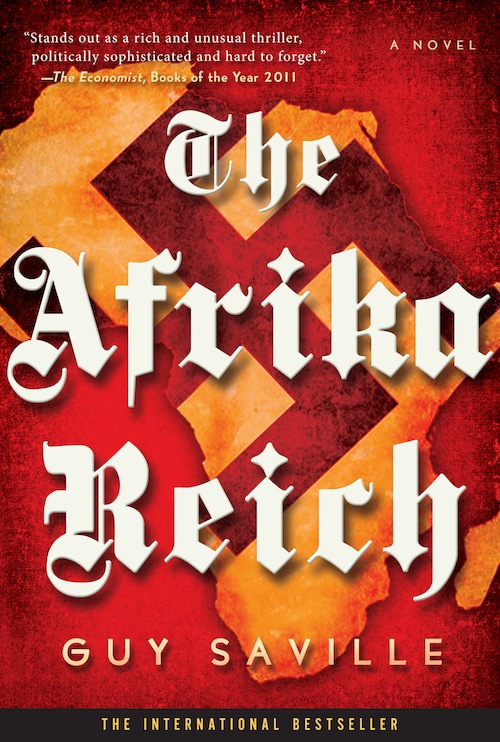

Take a look at alternate history thriller, The Afrika Reich by Guy Saville, out now:

Africa, 1952. More than a decade has passed since Britain’s humiliation at Dunkirk brought an end to the war and the beginning of an uneasy peace with Hitler.

The swastika flies from the Sahara to the Indian Ocean. Britain and a victorious Nazi Germany have divided the continent. The SS has crushed the native populations and forced them into labor. Gleaming autobahns bisect the jungle, jet fighters patrol the skies. For almost a decade an uneasy peace has ensued.

Now, however, the plans of Walter Hochburg, messianic racist and architect of Nazi Africa, threaten Britain’s ailing colonies.

Sent to curb his ambitions is Burton Cole: a one-time assassin torn between the woman he loves and settling an old score with Hochburg. If he fails unimaginable horrors will be unleashed on the continent. No one – black or white – will be spared.

But when his mission turns to disaster, Burton must flee for his life.

It is a flight that will take him from the unholy ground of Kongo to SS slave camps to war-torn Angola – and finally a conspiracy that leads to the dark heart of The Afrika Reich itself.

PART 1

GERMAN KONGO

Never wage war with ghosts. –African Proverb

CHAPTER ONE

Schädelplatz, Deutsch Kongo

14 September 1952, 01:14

Nine minutes. He had nine minutes to exorcise a lifetime.

Burton Cole sat at Hochburg’s desk, sweat trickling behind his ears. He was dressed in the uniform of a Sturmbannführer, an SS major: black tunic and breeches, Sam Browne belt, jackboots, swastika armband on the left sleeve. His skin crawled beneath the material. To complete the look, his hair had been cut short, his beard shaved; the skin on his cheeks felt raw and exposed. Chained to his wrist was an attaché case empty except for two items: a pouch fat with diamonds and, concealed inside that, a table knife.

The knife had been his mother’s, from a service used only for company. He still remembered the way she would beam as she laid the table for visitors, the flash of silver. That was—what?—when he was eight or nine. Back then he struggled to slice meat with it; now it was as deadly as an ice pick.

He’d spent years sharpening it to a jagged point for this very moment, never once believing it would come.

But just as Burton opened the case to grasp the knife, Hochburg held up his hand. It was an immense, brutal paw that led to an arm straining in its sleeve and the broad shoulders of a swimmer. The movement itself was languid—a lazy version of Hitler greeting the ranks.

“The diamonds can wait, Sturmbannführer,” he said. “First I must show you something.”

Ackerman warned him this might happen. Hochburg had shown all the previous couriers, shown everyone, no matter what their rank. It was his great pride. Indulge him, Ackerman advised. Do nothing to arouse his “suspicions.” There’ll be plenty of time for the kill.

Burton glanced at his watch. Everything had gone wrong tonight; now he felt crushed by the lack of seconds. This was not how he’d envisioned the moment. In his dreams, time stood still; there was opportunity for talk and torment.

And answers to all his questions.

Hochburg rose from his desk. The office around him was austere. Naked wooden floors, simple furniture. There was a gun cabinet in the corner and shelving for hundreds, possibly thousands, of books—though not a single volume filled them. Overhead, a fan remained motionless despite the humidity of the night. Although dark patches were spreading across Burton’s shirt, Hochburg looked as if his body were chilled to the bone. The only decoration in the room was the obligatory portrait of the Führer, another of Bismarck, and maps.

Maps of Aquatoriana, Deutsch Ostafrika, DSWA, Kamerun, Kongo, Muspel: all the dominions of Nazi Africa. The cartography of enslavement. Every last hectare pored over, charted, claimed. In the first years of conquest, they had been governed by the Kolonialpolitisches Amt, the KPA, a haphazard civil administration. Later, the SS took control.

Hochburg moved toward the opposite end of the room, where French doors led out to a veranda.

Burton hesitated, then got to his feet and followed. His jackboots pinched with every step. Hochburg was already on the veranda. Above him hung a silent wind chime. He spread his arms with a messianic sweep. “Magnificent, isn’t it?” he declared in a baritone that sounded raw from cognac, even though Burton knew he was a teetotaler. “A thing of wonder!”

The official headquarters of the Schutzstaffel, the SS, may have been in Stanleystadt—but this was the real power base of Deutsch Kongo. Burton had arrived through the front entrance, past the cranes that were still erecting the imperial façade. The quadrangle below him was at the rear, the hidden part of Hochburg’s fiefdom, used for ceremonial occasions. No one but the SS were allowed here.

It was the size of a parade ground, with several stories of offices on all sides and, according to Ackerman, cellars that went as deep below as the floors above. Bureaucracy and torture: two pillars of Nazi Africa. There were guard towers on each of the far corners; a patrol stalking the perimeter with a Doberman. Enough barbed wire for a concentration camp. But it was the ground that most caught Burton’s attention. Searchlights dived and soared over it. For a second he stood dumbfounded at the sheer scale of it. The sheer barbarity. His father would have wept at its sight.

Then his stomach curdled.

“A wonder!” repeated Hochburg. “You know, when the Reichsführer first saw it, he clapped his hands in delight.”

“I heard that story,” said Burton. “I also heard he filled two sick bags on the flight home.”

Hochburg stiffened slightly. “The man has a poor constitution; we gave him a sumptuous dinner.”

Burton glanced at the square again, then raised his eyes to the murk of the jungle beyond. Somewhere out there, concealed among the symphony of cicadas and tree frogs, were the rest of his men.

He imagined them: hearts jumpy but mouths set, faces thick with camouflage, counting down the final minutes on their watches. Patrick would already be slowing his breath to maximize the accuracy of his shot . . . assuming, of course, that they were even there. The team had gone their separate ways twenty-four hours earlier, and Burton had no way of knowing if the others had made it to their positions. It was the one flaw in the plan. He might be about to leap into the abyss—with only darkness to break his fall.

“How many would you say it took?” continued Hochburg.

“I’ve no idea, Oberstgruppenführer,” replied Burton. “A thousand?”

“More. Much more.” There was a gleam in his eyes. They were the color of coffee beans and not how Burton remembered them. When they glinted in his nightmares they were black—black as the devil’s hangman. But maybe that was just the years in between. It wasn’t the only difference. Hochburg had also lost his hair, every last follicle of it.

Burton offered another guess. “Five thousand?”

“More still.”

“Ten?”

“Twenty,” said Hochburg. “Twenty thousand nigger skulls.”

Burton looked back at the quadrangle and its gruesomely cobbled square. It gave Hochburg’s headquarters their name: the Schädelplatz. The square of skulls. Inside him, something screamed. He saw children torn from parents, husbands from wives. Families left watching the horizon for loved ones who would never return home to smile and bicker and gather round the fire. Every skull was one more reason to kill Hochburg.

He saw the view of his childhood, the dark jungle of Togoland. He saw his mother’s empty room.

Burton struggled to keep his voice level. “Can you walk on it?”

“You can turn panzers on it.”

“How come?” His brain could only supply nonsense. “Have they been fired? Like tiles, to make them hard.”

“Fired? Like tiles?” Hochburg stiffened again . . . then roared with laughter. “You I like, Sturmbannführer!” he said, punching his shoulder. “Much better than the usual couriers. Obsequious pricks. There’s hope for the SS yet.”

With each word, Burton felt the breath wrenched out of him. He suddenly knew he couldn’t do it. He had killed before, but this—this was something else. Something monumental. The desire to do it had been a part of his life for so long that the reality was almost like turning the knife against himself. What would be left afterward?

Burton tried to glance at his watch, but it caught on his sleeve. He was running out of time. On the veranda, the wind chime tinkled briefly.

He must have been crazy to think he could get away with it, that Hochburg would reveal his secrets. Here was a man dedicated to making silence from living, breathing mouths.

Then the moment passed.

At 01:23, the north side of the Schädelplatz would vanish in a fireball. By then he’d be on his way home, justice done, Hochburg dead. He’d never have to look backward again. The future would be his for the taking.

“Your diamonds,” Burton said, moving decisively toward the study.

But Hochburg barred his way, his eyes drained of humor. He seemed to want reassurance, to be understood. “We have to cleanse this place, Sturmbannführer. Let the flames wipe Africa clean. Make it as white as before time. The people, the soil. You understand that, don’t you?”

Burton flinched. “Of course, Herr Oberstgruppenführer.” He tried to pass.

“Any fool can pull a trigger,” continued Hochburg, “or stamp on a skull. But the square, that’s what makes us different.”

“Different from who?”

“The negroid. We’re not savages, you know.”

In his mind, Burton could hear the precious seconds counting down like a tin cup rapped on a tombstone. He tried to move forward again. This time Hochburg let him through—as if it had been nothing.

They resumed their positions at the desk.

Hochburg poured himself a glass of water from a bottle in front of him—Apollinaris, an SS brand—and sent it down his throat in a single, gulpless motion. Then he reached beneath his black shirt for a chain around his neck. He seemed greedy for his loot now. On the chain was a key.

Burton released the attaché case from his wrist and set it on the desk between them, feverishly aware of the blade hidden inside. He thought of the fairy tales Onkel Walter (his gut convulsed at the words) used to read him at night, of Jack lifting the ogre’s harp and it calling to its master. For a moment he was convinced the knife would also speak out, warn Hochburg of the looming danger, its loyalty to Burton forgotten in the presence of the hand that had once grasped it.

Hochburg took the case, placed the key from his neck into the left-hand lock, and gave it a sharp turn, like breaking a mouse’s neck. The mechanism pinged. He swiveled the case back. Burton inserted his own key into the second lock. Another ping. He lifted the top and slid his hand in, finding the bag of diamonds. He took it out, the knife still hidden inside the pouch, and stared at Hochburg. Hochburg looked back. A stalemate of unblinking eyes.

Ask, a voice bellowed in Burton’s head; it might have been his father’s.

What are you waiting for? Ask!

But still he said nothing. He didn’t know why. The room felt as hot as a furnace; Burton was aware of the sweat soaking his collar.

Opposite him, Hochburg shifted a fraction, clearly not used to such insubordination. He ran a hand over his bald head. There was not a drop of perspiration on it. In the silence, Burton caught the prickle of palm against stubbly scalp. So not bald, shaved. Any other time he might have laughed. Only Hochburg possessed the arrogance to believe his face needed something to make it more intimidating.

Burton’s fingers curled around the handle of the knife. Very slowly he withdrew it from the pouch, all the while keeping it out of sight.

Hochburg blinked, then leaned forward. Held out a grasping claw. “My diamonds, Sturmbannführer.” He offered no threat, yet there was confusion in his eyes.

Burton spoke in English, his mother’s language; it seemed the most appropriate. “You have no idea who I am, do you?”

Hochburg’s brow creased as if he were unfamiliar with the tongue.

“Do you?”

“Was?” said Hochburg. “Ich verstehe nicht.” What? I don’t understand.

In those restless nights before the mission, Burton’s greatest anxiety had been that Hochburg might recognize him. It was twenty years since they’d last seen each other, but he feared that the boy he’d been would shine through his face. Throughout their whole meeting, however, even with their eyes boring into each other’s, there hadn’t been the slightest tremble of recognition.

Now something was creeping into Hochburg’s face. Realization. Alarm. Burton couldn’t decipher it. Hochburg glanced at the portrait of Hitler as if the Führer himself might offer a word of explanation.

Burton repeated his question, this time in German, revealing the knife as he spoke. The blade caught the lamplight for an instant—a blink of silver—then became dull again. “My name is Burton Cole. Burton Kohl. Does it mean anything to you?”

The faintest shake of the head. Another glimpse toward the Führer.

“My father was Heinrich Kohl. My mother”—even after all this time, her name stumbled in his throat—“my mother, Eleanor.”

Still that blank look. Those empty brown eyes.

If the bastard had hawked their names and spat, if he had laughed, Burton would have relished it. But Hochburg’s indifference was complete. The lives of Burton’s parents meant no more to him than those pitiful, nameless skulls on the square outside.

He had planned to do it silently, so as not to bring the guards hammering at the door. But now he didn’t care.

Burton leapt across the table in a frenzy.

He crashed into Hochburg, hitting the bottle of water. Shards of it exploded everywhere. Burton grabbed the older man’s throat, but Hochburg was faster. He parried with his forearm.

They both tumbled to the ground, limbs thrashing.

Hochburg swiped ferociously again, snatched at Burton’s ear as if he would rip it off. Then he was grasping for his Luger.

Burton clambered on top of him. Pushed down with all his weight. Pointed the knife at his throat. Hochburg writhed beneath him. Burton slammed his knee into Hochburg’s groin. He felt the satisfying crush of testes. Veins bulged in Hochburg’s face.

Outside the room there was shouting, the scrape of boots. Then a tentative knock at the door. It locked from the inside, and no one was allowed entry without the express command of the Oberstgruppenführer, even the Leibwachen—Hochburg’s personal bodyguards. Another detail Ackerman had supplied.

“You recognize this knife,” hissed Burton, his teeth bared. “You used it often enough. Fattening yourself at our table.” He pushed the blade tight against Hochburg’s windpipe.

“Whoever you are, listen to me,” said Hochburg, his eyeballs ready to burst. “Only the Führer’s palace has more guards. You can’t possibly escape.”

Burton pushed harder, saw the first prick of blood. “Then I’ve got nothing to lose.”

There was another knock at the door, more urgent this time.

Burton saw Hochburg glance at it. “Make a sound,” he said, “and I swear I’ll cut your fucking tongue off.” Then: “My mother. I want to know. I . . .” He opened his mouth to speak again, but the words died. It was as if all Burton’s questions—like wraiths or phantoms—had weaved together into a thick cord around his throat. He made a choking sound and became deathly still. The blade slackened on Hochburg’s neck.

Then the one thing happened that he had never considered. Burton began to weep.

Softly. With no tears. His chest shuddering like a child’s.

Hochburg looked more bewildered than ever but took his chance. “Break down the door!” he shouted to the guards outside. “Break down the door. An assassin!”

There was a frantic thump-thump-thump of boots against wood.

The sound roused Burton. He had never expected to get this opportunity; only a fool would waste it. He bent lower, his tear ducts still smarting. “What happened to her?”

“Quickly!” screeched Hochburg.

“Tell me, damn you! I want the truth.”

“Quickly!”

“Tell me.” But the rage and shame and fear—and, in the back of his mind, the training, that rowdy instinct to survive—suddenly came to the fore.

Burton plunged the knife deep and hard.

Hochburg made a wet belching noise, his eyelids flickering. Blood spurted out of his neck. It hit Burton in the face, a slap from chin to eyebrow. Burning hot. Scarlet.

Burton stabbed again and again. More blood. It drenched his clothes. Spattered the maps on the walls, running down them. Turning Africa red.

Then the door burst inward and two guards were in the room, pistols drawn. Faces wide and merciless.

CHAPTER TWO

It was called dambe. Burton had learned it as a kid on the banks of the River Oti, in Togo, taught by the orphans his parents were supposed to redeem. Learning to kick and punch and head-butt with the unbridled ferocity of a fourteen-year-old. But always at night, always away from Father’s soulless eyes. Inventing excuses for the splits and swellings that blotted his face. Soon he was beating the boys who instructed him. They said he had the yunwa for it—the hunger. That was after his mother had left them.

The two Leibwachen glanced down at Hochburg, their mouths sagging with disbelief. Blood continued to gush from his throat, weaker with each spurt.

Burton sprang up. Three strides and he was at the door, his left hand held out in front of him straight as a spade, the right curled into a ball of knuckles tight at his armpit, his legs bent like a fencer’s.

He stamped his boot down on the closest Leibwache’s shin. The man buckled as Burton lunged forward and—snap—fired a fist into his face. A head butt and the guard was rolling on the floor.

The second Leibwache spun his pistol at Burton and fired, the shot missing his head by a fraction. Burton felt his eardrum thunderclap and muffle at the closeness of the bullet. He twisted low and rammed his elbow into the Leibwache’s chest bone. The guard doubled up, his pistol skittering across the floor.

Past the open door, Burton heard the sound of boots on stairs.

The winded Leibwache lurched toward Burton, who ducked underneath him and, coming back up, thumped his wrist, the hannu, onto the back of his neck where vertebrae and skull connected. The man dropped lifelessly.

In the room beyond, another guard appeared, roused by the gunshot. For an instant his eyes met Burton’s. Then Burton slammed the door shut.

The click of the bolt.

There was no double-locking mechanism, so Burton dragged Hochburg’s desk to the door, stood it on end, and jammed it hard against the frame. It would buy him a few extra seconds. He was lathered in sweat, even the material of his breeches sticking to his thighs. He undid his top buttons and tried to breathe. His watch read 01:21.

Burton reached down for one of the Leibwache’s Lugers. He wished he had the reassuring handle of his Browning to grip, but the pistol was in Patrick’s care. The Luger would have to do. He checked its firing mechanism and clip (seven shots left) and hurried toward the veranda.

Then he hesitated.

He looked back at Hochburg’s body. The bleeding had stopped. He was completely still except for his left foot, which twitched sporadically, its motion almost comic. Burton’s last chance of knowing about his mother—why she’d vanished, what had happened—was gone forever.

The Afrika Reich © Guy Saville 2013