“And this his majesty will think we have reason to expect when he reflects that he is no more than the chief officer of the people, appointed by the laws, and circumscribed with definite powers, to assist in working the great machine of government erected for their use, and consequently subject to their superintendence.” – Thomas Jefferson

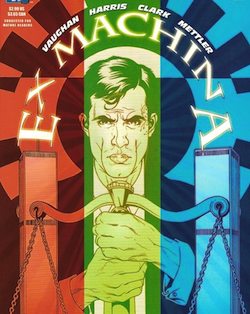

What if a superhero became the Mayor of New York City? That’s the central question at the heart of Brian K. Vaughan’s 50-issue maxi-series Ex Machina with artist Tony Harris, which tells the story of Mitchell Hundred, a former civil engineer who gains the ability to communicate with machines in a freak accident and is later elected to office after saving the second tower from going down on 9/11 (the series is very clearly set in an alternate reality, a detail which is integral to the plot). The series follows Hundred’s four years in office, and while it does feature plenty of superheroics in flashbacks to Hundred’s time as “The Great Machine” as well as the ongoing mystery of his powers, the central focus of the story is on Hundred’s career as a politician, and the trials and tribulations that he faces as the governing figure of the largest city in America.

Spoilers ahead for a good chunk of the series.

Vaughan claims that the series was “born out of [his] anger with what passes for our current political leadership (on both sides of the aisle),” and is remarkably able to explore both sides of the issues in a fair and balanced light. As Mayor Hundred himself explains, “I’m not a liberal or a conservative. I’m a realist.” Though he ran as an Independent, he recruits a young black Democrat named Dave Wylie as his Deputy Mayor, a devout Catholic and former nurse named Candy Watts as his Chief of Staff, and a Republican Police Commissioner with a vendetta against vigilantism. He makes it clear that he wants this team of opposites to challenge him, as well as each other, so that together they can make the best decisions for the entire city of New York, rather than a select demographic or targeted voter base. While Vaughan acknowledges the ups and downs of both the left and the right, he also realistically portrays the difficulties of a nonpartisan, centralist view—and demonstrates why that idealized middle ground might not work so well after all.

Full disclosure, I do personally tend to align myself more with the left (though like most people, my muddled feelings are endlessly complicated). That being said, I am not intending to espouse any personal political agenda with this article, and instead hope to explore the ideas expressed in the text of Ex Machina as objectively as I possibly can. The truth (and irony) is, I wish we had more politicians like Mitchell Hundred. But as Brian K. Vaughan demonstrates throughout the series, even that sounds like a better idea in theory than in practice.

On Education

Education is of course always a hot button topic, and in a city as large and diverse as New York, the quality of education varies quite dramatically. Early on in the series, Mayor Hundred proposes a complete overhaul of the New York City education system, but until this overhaul is complete, he suggests that the city consider school vouchers to encourage families to send their children to private schools in the meantime, so that the remaining children won’t be lost in the shuffle. “This would be a temporary patch while we try to fix a broken system,” he explains. “Sometimes, we have to accept necessary evils while we’re addressing larger problems of inequality.” Deputy Mayor Wylie, on the other hand, feels strongly against such objectivity when dealing with children—“These are children, not a goddamn highway overpass!”—and believes that a voucher system would send a message that Hundred and his team are giving up on public education entirely. Of course, Wylie has the means to send his own children to a private school, but not all families in New York are as lucky. Realizing his own hypocrisy, Wylie pulls his children out of the prestigious Horace Mann School, and supports Hundred’s decision to overhaul the largest public education system in the free world. (Or at least supports the decision to consider the voucher program…)

On Gay Rights

Deputy Mayor Wylie’s children aren’t the only familial affiliation of his that complicate issues in the story. Shortly after 9/11 , Wylie’s brother, a 9/11 first responder, firefighter, and a homosexual, wishes to be married to his long-term partner (ironically, a Log Cabin Republican), and asks for Mayor Hundred to oversee the ceremony in Central Park. Despite warnings from his entire staff about the damage that this might do to his public image (both in terms of popularity, and in terms of the public perception of Mitchell’s own sexuality), Hundred proceeds regardless, feeling that it would be wrong to deny an NYC firefighter hero of his happiness.

When a priest asks what he would say to religious groups offended by the idea of homosexuality, Hundred responds that that he would say the same thing about a divorced Catholic seeking a marriage license—while he respects peoples’ religious beliefs, his duty is to uphold the laws of the state, not the church. Hundred asserts that denying anyone the right to marry would violate constitutionally protected rights to privacy, equality, and pursuit of happiness—and that technically, if marriage is a traditionally religious institution, then the state government shouldn’t allow anyone to be married in order to uphold the separation of church and state, and should instead allow civil unions for all constituents, with the option to have their ceremonial marriage recognized by the religious institution of their choice.

While this decision may seem explicitly liberal—a fact which is not lost on the more conservative citizens of New York—Hundred’s reasoning is grounded less in pushing a typically “liberal agenda” and more about keeping the government out of the way of the people’s decisions for happiness. Ultimately, this rationale leads him to a close friendship with Father Zee, the priest who originally questioned him.

On Defense & Security

On Defense & Security

Unsurprisingly for a former superhero, Mitchell Hundred is a very serious politician when it comes to issues of security and defense, and although he’s put his past as a masked vigilante behind him, he’s not afraid to occasionally bend the rules and re-don the costume or take justice into his own hands if he feels it’s necessary. In fact, his belief in doing what needs to be done to keep the people safe manages to repeatedly irritate the peace-loving left (many of whom supported him as vigilante, another instance of political hypocrisy that does not go unnoticed). At one point during a heightened terrorism alert, Hundred proposes police checks at all subway stations of every passenger, turning an average trip on the F train into the equivalent of an airport security check.

While the police technically have the resources and manpower to do this, most of the force sees this as unnecessary, causing them to only check “suspicious” persons—which of course leads to racial profiling, and even the accidental death of a minor, both of which paint the Mayor in a negative light. While he manages to salvage his image by returning to his vigilante roots to stop a legitimate terrorist, Hundred still learns an important lesson about taking such a firm stance on security. “You tried to do the logical thing,” a National Guardsman tells him, “but we’re at war with an irrational enemy. This wasn’t your fault,” further reminding the reader that as much as we might appreciate Hundred’s attempts at centrist realist governing, that kind of pragmatism can still sometimes be problematic.

While it’s not explicitly “defense,” Mitchell Hundred also really hates car alarms that go off unnecessarily, and understandably so, and he puts an ordinance into place that hits people with a $600 fine on the third offense for car alarms that go off accidentally and wind up endlessly blaring through the streets. This, of course, is seen as a form of fascism by some people (because Americans are always generous with their political name-calling). Hundred does eventually realize that this ordinance might be over-stepping his bounds as Mayor, but c’mon, we’ve all experienced one of those loud, obnoxious car alarms that just keeps going off with no end in sight, so really, can you blame the guy?

On Health Care and Drugs

At the start of his term in 2002, One of the first situations that we see Hundred face is the proposal of a smoking ban in New York City restaurants. While Hundred would personally like to pass this law (as he fully understands and empathizes with the health risks and discomforts of secondhand smoke), he admits that he is more concerned with the well-being of the servers in the food industry. Banning smoking in restaurants will mean less tips for waiters and bartenders, and he would rather not steal any more much-needed income from food industry professionals in order to push a personal agenda to appease only half of the population.

Stealing a move from Bill Clinton, Mitchell Hundred also publicly admits to having used marijuana, which opens up a firestorm in the media. Shortly thereafter, a woman immolates herself on the steps of City Hall, in protest of the city’s policies in dealing with drugs. As it turns out, this woman was the mother of a pot dealer than Mitchell had caught and arrested during his days as The Great Machine. In a flashback, we see The Great Machine vehemently pursuing and beating up this man for dealing—which is especially ironic once we learn that Hundred actually self-medicates with marijuana to ease the constant machine chatter caused by his superpowers. (He can make machines do what he wants, but he can’t otherwise shut them out.)

Seeing his own hypocrisy and learning from his mistakes, Hundred hopes to overhaul drug laws in New York City, starting with the decriminalization of marijuana. But his cabinet ultimately advises against it, realizing that if City Hall gives in to the pressure of one self-immolating protester, they’ll soon have all manner of activists and special interests groups lighting themselves on fire in order to get what they want. As much as Hundred wants to decriminalize it, he understands that this will open an unwanted floodgate that will do more harm than good, and must publicly remain on the conservative side for the better good of the city.

On Bipartisanship

At the start of his term as the Mayor of New York City, Mitchell Hundred promises the people a “new era of bipartisanship.” Even when the Governor sends a Republican representative down from Albany to bully and blackmail Mitchell into working on their side, for their interests, Mitchell takes a firm stand, making it clear that he will not answer to any political party but the people themselves. In general, Mayor Hundred’s neutral independent stance seems like a great idea in theory, as he does not have to concern himself with making decisions in accordance with or to appease party lines, but he soon realizes the difficulties of remaining impartial at all times, even when he might agree with one party over a certain issue.

When the Republican National Convention comes to New York City in 2004, Hundred is asked to be the keynote speaker. Although he is initially inclined to turn down the offer in order to maintain his image of neutrality, he realizes that doing so would also make him an enemy of the Republican party, which is something that an Independent politician could not afford. Furthermore, he realizes that by refusing to allow the RNC to take place in New York, he is robbing the city of a potential $3 million dollars in revenue.

(There’s also an entertaining bit where Hundred struggles with what tie to wear, as he doesn’t want to explicitly come out in support of either party, but one of his advisors warns that wearing a purple tie for Independence will only perpetuate the rumors that Mitchell is gay.)

After the convention, the Republicans attempt to recruit Mayor Hundred as the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. With his history of vigilantism and conservative defense policies, they believe that he will be a particularly effective member of the U.N. Security Council and a true protector of New York City. Also, putting an Independent in that seat means that it doesn’t end up going to the Democrats, and as everyone knows, preventing the opposing party from gaining influence is often the highest priority of a political party. But the Republicans also acknowledge that, despite Hundred’s history of certain leftist leanings, he might actually have what it takes to make a difference. “I thought you were all bark and and no bite, another toothless Idealist who’d fade away faster than a Howard Dean scream,” says Trip, one of the Governor’s lackeys. “I’m thrilled to see I was wrong.”

On Freedom of Speech

Throughout his term in office, Hundred is frequently faced with approving (or at least accepting) plans for public demonstrations by groups with which he would rather have no affiliation. He receives a great deal of criticism for allowing Iraq War protesters to march through the city only nine months after 9/11, but he believes it is not his place to restrict freedom of speech, or to publicly support or oppose federal matters (a policy which he strongly encourages other city employees to follow as well). At one point, a city grant for the Brooklyn Museum of Art leads to the display of a painting of Abraham Lincoln with “the n-word” sprawled across it. While this technically means that the Mayor gave money to the museum to display offensive material with which he does not agree, he also realizes that forcing the museum to remove the painting would be restricting their (and the artist’s) right to freedom of speech, and he does not believe in censorship. Ultimately, Hundred uses diplomacy to get the artist to willingly remove the painting (by dressing up as a masked vigilante and vandalizing her own offensive artwork, no less).

In the wake of 9/11, a resurgence of the Klu Klux Klan, framing themselves as a “white American interests group,” wishes to hold a rally in Central Park. They compare their white hoods to the mask of Mitchell Hundred as The Great Machine, citing a history of vigilantism and the protection of identities in America. Once again, Mayor Hundred refuses to deny them their right to free speech, as much as it pains him to do so. However, he organizes a counter-rally in support of tolerance directly across the Klan rally, and makes a public statement that hiding behind masks is a true sign of cowardice, which is why he went public and retired his own masked superhero identity.

On the Environment

Hundred also ends up butting heads with a conservative newspaper editor, who believes that the Mayor’s new environmental laws requiring all newspapers to be printed on recycled paper is in fact a restriction of the freedom of the press. Hundred asserts that the press is guaranteed the freedom to write whatever they would like, just not to print on whatever material they would like. Still, the editor insists that the government has no place regulating the quality of newsprint, and as much as Hundred’s recycling plans are forward-thinking and looking towards a more sustainable future, Hundred realizes that he has not enforced similar regulations on printed books or comic books—neither of which are ever recycled—and that perhaps this regulation is hypocritical and overstepping his boundaries of power after all.

On Reproductive Rights

Mitchell Hundred is caught in a predicament when it comes to the “morning after pill.” On one hand, he doesn’t want to further alienate the conservative Christian Right, who are already upset with his decision to support gay marriage. Still, he feels that easy access and distribution of the pill is necessary for the city, especially since the rate of teen pregnancy is rapidly rising. That being said, he is not comfortable spending taxpayer dollars on emergency contraception, either. “Public servants should try to avoid genital politics and concentrate on actually getting shit done,” he explains.

Ultimately, Hundred is saved by the disparate politics of his most trusted advisors: both the conservative Catholic Chief of Staff Candy Watts and the Democrat Deputy Mayor Dave Wylie end up leaking Wylie’s extremely liberal contraceptive plan proposal, thus making Hundred’s centralist proposal appear like a better alternative in comparison, rather than a left-leaning compromise, and helps Hundred save face with the Christian Right.

On Taxes

At the start of his final year in office, Mayor Hundred announces that he will not be seeking re-election, as he feels it is more important for him to spend his time continuing to fix the city, rather than allowing a campaign to distract him from his job. (I know I said I’d try to keep personal politics out of this, but I think that’s an idea that all of us can get behind.) Unfortunately, Hundred also announces a significant increase in taxes. He feels that it is important for him to accomplish everything that he promised when running for office, and the only way to do this and balance the budget is with increased tax revenue. As he is not seeking re-election, he is unconcerned about how this might affect his popularity. To enforce his reasoning, he quotes Adam Smith, the so-called “father of Capitalism”: “It is not very unreasonable that the rich should contribute to the public expense. Not only in proportion to their revenue but something more than in that proportion.” He readily acknowledges that taxes are a necessary evil, but, like any good engineer, he is still committed to fixing the broken machine of the city.

Over the course of 50 issues and 4 years in office, Mitchell Hundred shows what is possible when politicians refuse to allow themselves to get bogged down in the, well, in the politics of governing. His determination to fix an inherently broken political machine as only an engineer can is, I think, incredibly admirable, regardless of which side of the political spectrum you might fall on. “Government should be a safety net, not a hammock,” he says at one point. His policies demonstrate this philosophy, and again, I think it’s an idea that most people can truly support: a government that helps all of the people, but without letting us lounge around and do nothing. Mitchell Hundred believes that a politician’s role is, like an engineer, to simply keep the gears turning and let the people continue to live and work the way they want to.

However, the writer of the series, Brian K. Vaughan, consistently demonstrates that even though this sounds like a simple, obtainable goal, there are endless amounts of complications and exceptions that keep the machine from ever truly running smoothly. Ex Machina shows that politics are never, ever black and white—and that perhaps there are too many varying shades of grey in between, as well. “I know how to work the political machine, but the gears just turn too damn slow inside City Hall,” Mayor Hundred says at one point, and in a shocking twist ending (serious spoilers ahead), we discover that he ends up being elected as Vice President of the United States of America in 2008 on the Republican ticket alongside John McCain.

Perhaps to some readers this doesn’t seem like such a surprise—as much as Hundred is seen to stand for social freedoms and often personally supports regulations, he also understands objectively the need for less government interference, and is able to remain firm in his moral objectivism without compromising himself. But in a comic book about a superhero-turned-politician who must contend with invaders from parallel realities while balancing budgets, that kind of idealism might require the greatest suspension of disbelief.

Thom Dunn is a Boston-based writer, musician, homebrewer, and new media artist. He enjoys Oxford commas, metaphysics, and romantic clichés (especially when they involve robots). He firmly believes that Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing” is the single worst atrocity committed against mankind. Find out more at thomdunn.net