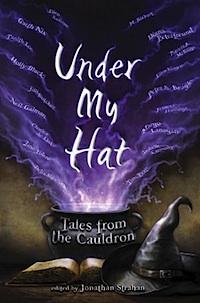

Under My Hat: Tales from the Cauldron is Jonathan Strahan’s newest anthology, a gathering of seventeen stories and one poem about witches and witchcraft directed to a young adult audience. As he says in his introduction:

Under My Hat […] started life several years ago as a gift for my two daughters, Jessica and Sophie. Some time ago Sophie, my younger daughter, asked if there was one of my books she could read. As I looked at the book I’d just completed, I realized I didn’t have one that was anywhere near suitable for, let alone interesting to, an eight year old girl, and so I set out to create a book just for Sophie and her sister.

From those warm beginnings, Strahan has constructed a pleasant and playful set of tales that’s quite a who’s-who list of writers of the fantastic, all handling the ever-present idea of the witch in the ways they see fit.

While his introduction notes wanting stories for a child of eight, the intended audience of this book seems to hover around the young adult category, and it is in fact published by Random House’s teen division. Many of the stories would be equally at home in an anthology marketed to adults, while others have a youthful focus and intent; in this sense, Under My Hat reminds me tonally of last year’s fabulous Welcome to Bordertown edited by Ellen Kushner and Holly Black. Unlike many of my favorite Strahan anthologies, this one isn’t full of heavy-hitting, intense stories—that’s not really the point, after all.

Many of these pieces are fun romps: action, adventure, intrigue, and of course, magic. Garth Nix’s “A Handful of Ashes” is one of this type: the setting is a private magical college, where the lead characters work as servants to pay for their education. A nasty older student and her relative are trying to do some bad magic, the lead characters are trying to stop them, and in the process they discover a sense of self and purpose not despite but because of their humble beginnings. Nix writes believable teenagers; his ways of exploring issues of bullying, class, and education in the context of this light tale are authentic rather than distracting. On the opposite end of the spectrum, Peter S. Beagle’s “Great-Grandmother in the Cellar” was an eerie, discomfiting piece. It was also one of the more memorable in the book, if nothing else for the alarming imagery that comes at the climax of the story as the great-grandmother’s shade runs out of patience with the young witch-boy she’s trying to defeat and save her great-granddaughter from. “Which Witch” by Patricia A. McKillip lacks much substance, but it’s good fun. The protagonist’s struggles to understand her crow familiar are comical, and the personalities of the crows themselves are just a riot. Really, I didn’t care much about the evil spirit that the protagonist’s band and the crows battle—and I don’t get the sense that the story did, either.

While nearly every story is concerned with coming of age and/or coming into one’s own, some explore that territory more directly than others. The offering from Jim Butcher, “B is for Bigfoot,” takes place at an indeterminate earlier point in the Dresden Files series. (The Harry Dresden of this story is a bit softer, more reminiscent of the early novels.) This story also deals with bullying; Harry helps a bigfoot’s half-human son develop a sense of his own subjectivity and power in the face of being bullied by a pair of brothers in his school. The underlying arguments about when and how it is appropriate to use one’s strength against others aren’t examined in much detail, but they are there. The sense of watching a pivotal, life-altering moment for the young half-bigfoot boy is real and personal. Holly Black’s “Little Gods” expressively paints a portrait of a young woman trying to find faith, a place, and a purpose through Wicca—and, at the moment of her greatest doubt, finding all of the above in a strange, impossible encounter at a Beltane celebration. The characters in this story are all well-realized and intimately familiar. Black has a particular way of writing teens on the cusp of adulthood that rings true, without saccharin over-simplification or exaggeration of emotion and personal need.

Of the strongest stories in the book, I had a few favorites: “Payment Due” by Frances Hardinge, “The Education of a Witch” by Ellen Klages, “The Threefold World” by Ellen Kushner, and “Crow and Caper, Caper and Crow” by Margo Lanagan.

Hardinge’s tale is a flat out revenge story, but a revenge story where a young witch uses her powers for the good of her un-world-wise grandmother. It’s one of the only pieces in which magic and witchery seem at both sinister and uproariously ridiculous; the scene in which the bailiff’s enchanted furniture runs away to the protagonist’s house was so vividly rendered that I did, actually, laugh out loud. The matter-of-fact and sly voice of the protagonist is also a pleasure to read, though the audience naturally feels a bit uncomfortable with the lengths that she goes to in teaching the man to be kinder via apt vengeance. I enjoyed the tension between ethical constraints and familial loyalty.

“The Education of a Witch” is, as I expect from Ellen Klages, subtle, with a foot planted in realism and another in the fantastic. While the story is familiar—ignored by her parents because of a new baby, a little girl discovers she might have magic—the particular depiction of the young girl and her romantic obsession with Maleficent are both unique and gripping. The faintly sinister ending sounded the ideal note for me, as a reader, between the innocence of childhood and the (often still innocent) cruelty of children. The uncertain nature of the magic, or if it exists at all, appeals to me as well.

Ellen Kushner’s “The Threefold World” and Jane Yolen’s “Andersen’s Witch” are both about writer-scholars (or writer-scholars to be) encountering magic, and how it alters their lives and their deaths fundamentally. However, of the two, I found Kushner’s to be much more evocative of a long life well-lived in the study of magic, history, and culture; Elias’s foolhardy insistence on discarding what he sees as his backwater history during his youth is pointed, and his eventual realization that his people have had a powerful history as well is equally so. The commentary on class, culture, and the construction of power out of stories is strong but understated, here. “The Threefold World” feels like a story in Elias’s own book of tales—focused, regional, and magical.

Finally, Margo Lanagan’s closing story “Crow and Caper, Caper and Crow” is one in which nothing much technically happens—an old witch travels far to bless her new baby granddaughter, who turns out to be the most powerful being she’s ever seen. However, the clever and stunning world-building locked it into my memory. At first, I believed the story to be a second-world fantasy; then, as the witch travels, we realize that she does in fact live in the modern world. The clashes between the old world and the new, magic and technology, are lovingly rendered and absolutely not even the point of the story. But, they’re so very strong as narrative background that they make the protagonist’s eventual decision to be there for her daughter-in-law when needed, rather than trying to outmuscle her, touching. The bond between women that develops, here, in a lineage of powerful women, is another high point for such a seemingly simple piece.

Finally, I should mention the poem by Neil Gaiman, “Witch Work”—a metered and traditional piece, it works well within its strictures to give both powerful imagery and a sense of narrative. I was glad to see at least one poem in Under My Hat; the subject seems to invite verse. (Shakespeare, anyone?)

Taken whole and on its terms, as a book for young readers that’s devoted to exploring the figure of the witch, Under My Hat is quite good. Great and relevant for the younger audience, pleasurable and fun for adults—a way to fill an afternoon or two with stories that are often genuine, often honest, and often playful.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. Also, comics. She can be found on Twitter or her website.