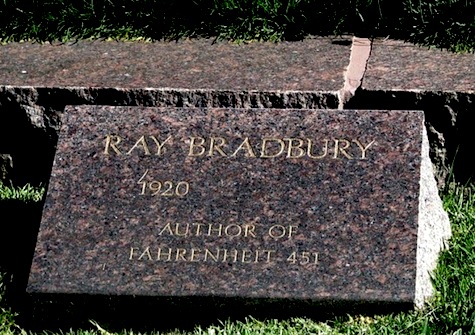

In the 20th Century he was comparable to Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov and Arthur C. Clarke. But Bradbury, in the ’40s and ’50s, became the name brand. Now they all, the BACH group, are gone.

He came out of Grimms Fairy Tales and L. Frank Baum‘s “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz”, the world’s fairs and Lon Chaney Sr., Buck Rogers and “Amazing Stories.”

Visiting a carnival at 12 brought him face to face with Mr. Electrico, a magician who awakened Bradbury to the notions of reincarnation and immortality. “He was a miracle of magic, seated at the electric chair, swathed in black velvet robes, his face burning like white phosphor, blue sparks hissing from his fingertips,“ he recalled in interviews. ”He pointed at me, touched me with his electric sword—my hair stood on end—and said, ’Live forever.’ Transfixed, Bradbury returned day after day. “He took me down to the lake shore and talked his small philosophies and I talked my big ones,” Bradbury said. “He said we met before. ’You were my best friend. You died in my arms in 1918, in France.’ I knew something special had happened in my life. I stood by the carousel and wept.”

He was loud and boisterous and liked to do a W.C. Fields act and Hitler imitations. He would pull all sorts of pranks, as a science fiction fan in the 1930s and 1940s. And he wrote a short story every week, setting a deadline: he would quit writing if he couldn’t sell one in a year. He sold his 50th. We came that close to having no Bradbury in our literature.

It’s telling that we read Bradbury for his short stories. They are stylish glimpses at possibilities, meant for contemplation. The most important thing about writers is how they exist in our memories. Having read Bradbury is like having seen a striking glimpse out of a car window and then being whisked away.

Often reprinted in high school texts, he became a poet of the expanding world view of the 20th century. He coupled the American love of machines to the love of frontiers. Elton John‘s hit “Rocket Man” is an homage to Bradbury’s Mars.

Bradbury chalked up his stories’ relevance and resonance to his dealing in metaphors. “All my stories are like the Greek and Roman myths, and the Egyptian myths, and the Old and New Testament…. If you write in metaphors, people can remember them…. I think that’s why I’m in the schools.”

Nostalgia is eternal for Americans. We are often displaced from our origins and carry anxious memories of that lost past. We fear losing our bearings. By writing of futures that echo our nostalgias, Bradbury reminds us of both what we were and of what we could yet be.

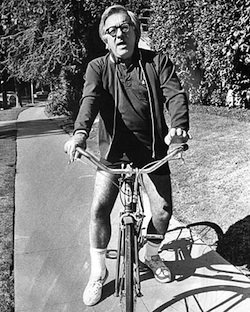

Like most creative people, he was still a child at heart. His stories tell us: Hold on to your childhood. You don’t get another one. In so many stories, he gave us his childhood—and it worked for us, too.

So Mr. Electrico was right in a way. His work will live forever.

Gregory Benford is an American science fiction author and astrophysicist. He is perhaps best known for his novel Timescape, which won both the Nebula and Campbell awards, and the Galactic Center Saga.