Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 25nd installment.

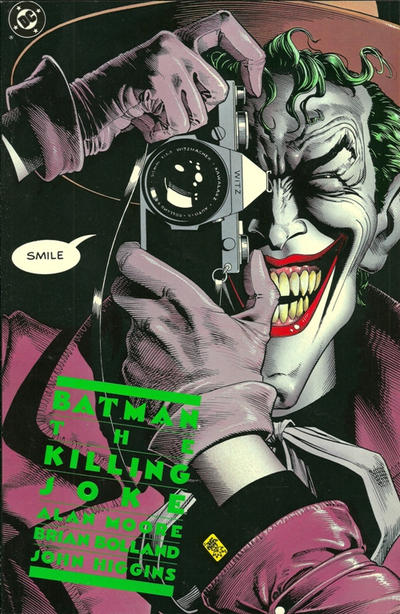

When it comes to Batman and Alan Moore, most people immediately think of his work with Brian Bolland on 1988’s Batman: The Killing Joke, and rightly so, as that was a particularly high-profile release from the (by then) famous writer of Watchmen and the most meticulously detailed superhero artist of his (or any) generation.

The Killing Joke marks Moore’s last major work for DC Comics, if we exclude his wrapping-up of the much-earlier-begun V for Vendetta and his later unplanned and undesired return under the company umbrella when DC purchased Jim Lee’s Wildstorm production company, and Alan Moore’s America’s Best Comics along with it.

And it was the last time Brian Bolland drew anything substantial for another writer, choosing to spend the decades since The Killing Joke’s release working on short comics of his own creation and hundreds of striking cover images for a range of publishers (but mostly DC).

Still, The Killing Joke isn’t Alan Moore’s best Batman story. That honor belongs to a comic that debuted a year earlier, a little story called…

“Mortal Clay,” Batman Annual #11 (DC Comics, 1987)

Coupled in the oversized annual with a Penguin story by Max Alan Collin and Norm Breyfogle, “Mortal Clay” recounts the tragic love story of Clayface III, aka Preston Payne, as drawn by Canadian comic book artist George Freeman.

Freeman, with his graceful, flowing linework and absurdly wide-jawed heroes, is no match for Brian Bolland in the rendering department, but he brings an edgy sense of whimsy to the pathos of “Mortal Clay.” It serves Moore’s script well, and while it looks a bit more like a traditional comic book story than the grim and menacing Killing Joke, there’s something unsettling about the garish Lovern Kindzierski colors trapped inside Freeman’s bold lines.

And it should be unsettling, because “Mortal Clay” begins with the internal monologue of the imprisoned Payne – as I mentioned, the third in a long line of Batman villains known as “Clayface,” and the one most obviously tragic from his very origins – and goes on to tell a tale of lost love and absolute derangement.

Preston Payne, former scientist, became Clayface III while searching to cure himself from an affliction, and like all scientists-who-go-too-far-in-the-classic-stories, his experiments cause unexpected side effects like…his flesh starting to melt off his bones, and his touch turning everyone else into flesh-melted freaks as well. All-in-all, not a successful day at the office for Payne.

This all happened back in the Bronze Age of Detective Comics, when flesh-oozing covers were all the rage.

What Alan Moore brings to the saga of Clayface III, while still keeping the misunderstood-yet-horrific-monster side of the character, is a deep and abiding love story. Preston Payne feels a love so strong for his beloved that nothing can keep him away. He thought he lost his Helena in the fire at the museum, when he battled with Batman ages ago, but after hiding in subway stations and wandering the streets of Gotham, homeless, he found Helena again. In Rosendale’s department store. In the window, more specifically. Helena, as Moore and Freeman indicate from the start of their story, is a mannequin.

I’ll note, for the official record, that the notion of Clayface III falling in love with a mannequin calls back to the end of the character’s first story arc, written by Len Wein, and recapped in fragmentary images and partial memories on the second page of Moore and Freeman’s tale. In Wein’s original, Preston Payne’s confused sense of reality led him to the insane state where the only woman he could be with, the only creature who could resist his deadly touch, was a woman who was never alive to begin with. A woman of wax (or plastic).

So Moore didn’t generate the kernel of the idea which powers “Mortal Clay,” but what he brings to it is the sadness that comes from telling the story from Clayface III’s point of view, and the tragicomedy of watching the events unfold from a readerly distance. Clayface’s mock-heroic narration (sample line: “In an unforgiving city, I had found redemption”), contrasting with the awkward pairing of a hideous supervillain and a life-size doll with a blank stare, provides the kind of frisson that makes the comic come to life with charming energy.

Preston Payne lives out his fantasy with his beloved, unliving, Helena: to have a “normal life,” with dinner at nice restaurants, time spent with friends, romance in the bedroom. Payne narrates his dream reality as we seem him live it, after-hours, in the silence of the empty department store, avoiding the mustachioed security guard.

Unfortunately, the relocation of Helena to the lingerie section devastates our would-be Casanova. He begins to seethe with jealousy, and an innocent security guard falls prey to Payne’s rage. The mystery of the melted flesh at the department store. Enter: Batman.

Moore builds towards the climax in customary fashion, with some physical altercations between Batman and Clayface III, while Helena looks on, blankly. Because Payne is the pseudo-hero of the piece, he actually defeats Batman, and its only when Payne falls down at the feet of Helena and weeps over everything that’s gone wrong in their “relationship” that Batman can recover. Instead of a finishing blow, Batman offers Payne a helping hand.

We cut to the final page of the story, a domestic scene with Clayface III and Helena sitting in front of the television, just like Archie Bunker and Edith as they, appropriately enough, watch All in the Family in their specially-designed Arkham Asylum cell. Clayface pops open a beer.

The final reversal? His narration: “Oh, I suppose we can tolerate each other enough to live together, and neither of us wants to be the first to mention divorce. But the love…the love’s all dead.”

George Freeman draws a grinning Clayface in the final panel. “She can’t live forever,” he thinks.

In essence it’s an extended version of a Moore “Future Shock,” like much of Moore’s other superhero work in the corners of the DCU. It’s sad and funny and cuts like a razor without taking itself at all seriously. It’s radically overshadowed by the Alan Moore Batman story that would follow a year later, undeservedly.

Batman: The Killing Joke (DC Comics, 1988)

Reportedly, The Killing Joke came about because Brian Bolland, after his majestic turn on the twelve-issue Camelot 3000 series at DC, was asked to do something for the bat-offices, and he said he’d do it if they would bring in Alan Moore to write it.

The expectation was that Moore and Bolland would provide the definitive retelling of the Joker’s origin. The ultimate Joker story. The idea may have come from Bolland, or from the bat-offices, or from the talks between the collaborators. The stories vary, but the idea of a Joker-centric story was there from the beginning.

I don’t know when Moore actually wrote the script for The Killing Joke, and where its creation falls on the timeline-of-Alan-Moore-drafts, but my understanding is that Bolland took an incredibly long time to draw the story, so that would place the original script for the book around the same time as Watchmen. And it shows, but not to its benefit.

The Killing Joke, in its original form (and in its multiple printings with variations on the cover lettering colors), was printed in the “Prestige Format” used for Frank Miller’s Dark Knight Returns a couple of years earlier. Brian Bolland was so unhappy with John Higgins original coloring on The Killing Joke that he later recolored the comic himself, when it was released in a hardcover in 2008.

Bolland’s colors look nicer – his palette more subtle – and he more clearly defines the flashback sequences with a muted scheme, but Higgins colors will always look like the “real” Killing Joke as far as I’m concerned, and the sickening greens and yellows and neon oranges might not be pleasing to the eye, but they create the horrible circus vibe that permeates the comic, like you’ve just staggered off a roller coaster and everything smells terrible all around.

For me, that’s not where The Killing Joke fails. The coloring, as much as it goes against Bolland’s intended aesthetic, isn’t the comic’s downfall.

Its downfall – and why it doesn’t hold up well to scrutiny two decades later – is in its inelegant attempts to do Watchmen-style storytelling with a story that doesn’t have the structural integrity to support it.

The “realism” of Watchmen works because the characters are pieces of machinery that Moore moves around his clockwork mechanism of plot, and the archetypes represented by the likes of the Comedian and Rorschach and Dr. Manhattan allowed Moore to play around with thematic patterns and symbolic recursion. The events in the story could be bleak, the violence could be harsh, because it fit into what was being built and it commented upon the genre conventions within which the story was told and reflected back on the anxiety of the real world at the time of its creation. I wrote all about it for an entire month.

The Killing Joke tries to use many of the same trappings: the camera moves at the opening and closing of the story, the nine-panel grid in the first scene, the degradation of heroic archetypes, the horrific violence, and a kind of arch “realism” that’s only realistic compared to that time Batman turned into King Kong.

Those techniques work here, in the sense that they convey a particular tone and style, and it’s one that, in 1988, was a radically different approach to Batman comics.

Or, it would have been, if Frank Miller hadn’t upended Batman two years earlier in his milestone work on the character, where he pushed the boundaries of violence and satire and recast the superheroic ideal in much more viciously parodic terms. Compared to Dark Knight Returns, Moore and Bolland’s work on The Killing Joke feels like two guys showing up late to the costume party, having rehearsed their wicked little skit for an hour too long, only to find out that someone had just improvised something similar, with unmatched manic energy.

But that was a problem with The Killing Joke upon its original release – it was in Frank Miller’s shadow immediately – so why did I bother to say that “it doesn’t hold up well to scrutiny two decades later”? What’s the added context that forces us to think about The Killing Joke differently now?

All of the comics since 1988. That’s what.

Reading The Killing Joke now is like being reminded, for page after page, of decades of bad Alan Moore riffs that have been done in the years since its original release. Though I labeled the “Mortal Clay” story the “more traditional” of the two Moore Batman tales when I discussed the former above, the truth is that more of the superhero comics produced now look like bastard children of The Killing Joke than they look like “Mortal Clay.” The average, non-comic-reading citizen might still have something like the pages of “Mortal Clay” in mind when they think about “comics” as a concept, but if you visit your local comic shop on Wednesday, and flip through the Marvel and DC new releases that clutter the shelves, you’ll see things that tend much closer to The Killing Joke end of the spectrum than toward the “Mortal Clay” end.

And what many of those comics are missing is exactly what The Killing Joke is missing: a sense of humor about itself, and any kind of meaning outside of the confines of its pages. The Killing Joke is about nothing more than the relationship between the Joker and Batman, and though it leans toward some kind of statement about the Joker and Batman being two sides of the same insanity, that’s still just an in-story construct that doesn’t have any thematic resonance outside of itself.

Alan Moore and Brian Bolland are extraordinary craftsmen. Two of the best to ever work in the comic book industry. So The Killing Joke can trick you into thinking that its more worthwhile than it actually is. After all, how can a comic by these two guys, that looks as detailed as this one is, that creates a genuine humanity for the man-who-would-be-Joker when he was a young man wearing a red helmet and a cheap suit, how can such a comic be anything less than amazing?

Because it’s cynical. And goes for cheap subversion at the expense of its own characters, just for shock value. And it has an absolutely terrible ending.

It’s a thin story, from start to finish. We get the Joker’s origin – his youthful desperation that led to him becoming the Red Hood and then the tragedy at Ace Chemicals that gave birth to the Clown Prince of Crime – and we cut back to that story as it unfolds, in contrast with the horrors unveiled by the Joker of today. Batman is a mere force of pursuit in the story. He’s the tornado that’s coming into circus town to destroy everything the Joker has built.

But what has the Joker built in the story? A funhouse of degradation, where a naked, dog-collared Commissioner Gordon is prodded and humiliated. Where this paragon of virtue is forced to look at naked pictures of his daughter, who has just been paralyzed by the Joker.

The whole middle of the story is like an adolescent tantrum against the father-figure of DC Comics and the traditions of Batman comics. But it’s embarrassing even to read about after we’ve all grown out of that phase. Yet, that stuff mentioned above is what people remember about The Killing Joke, and it has influenced an entire generation of creators to disembowel their superheroes and humiliate the good guys with more and more extreme situations.

Barbara Gordon remained paralyzed for 23 years, thanks to the events in this comic, and even in the reboot of the new 52, when Batgirl is back in action, DC editorial has stated that The Killing Joke still happened in whatever indefinable past exists for the rebooted characters. So the Moore and Bolland project has more than lingered.

It’s the ending of the book that still kills it for me, above all of the other issues I have with the story. Because the end is as phony as they come, not even in keeping with what Moore and Bolland have built – as objectionable and cheap as it may be – in the rest of the comic.

The end is Batman offering to help the Joker. Sympathy from the man who has seen good people literally tortured just to rile him up. And then the Joker tells…a joke. It’s a decent enough joke, but not one that would make anyone laugh out loud. And the final page? Batman and the Joker laughing together, as the police sirens approach.

Is that Moore and Bolland doing an insincere impression of the Silver Age comics where the Batman Family would end a story with a group laugh? No, I don’t think that’s a convincing interpretation.

Is it Batman cracking apart, showing his insanity in the end? No, that’s not the way Batman manifests his madness.

Is it Moore bailing out of the story, and ending a Joker-centric story with a laugh track because where else does he go after the sexual violence and base humiliation he’s perpetrated in the story? It seems so. It seems false – for Batman, for the story as a whole – and yet that’s how it ends.

If Moore were a 1980s movie director instead of an acclaimed comic scribe, he might well have ended with a freeze frame high five instead. It would have made as much sense.

The Killing Joke doesn’t deserve the lavish attention Brian Bolland paid to every single panel he drew. Though if you do find yourself reading the book again (or maybe for the first time, though I wouldn’t recommend it in either case), at least you’ll have all of his meticulous lines to look at. It’s something to distract you from the lack of substance in the story. The lack of heart beneath the surface.

You’re better off sticking with Clayface III. He’s a monster with great depths, in just a few pages.

NEXT TIME: Jack the Ripper? Alan Moore knows the score.

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. If he ever returns to Twitter, you should follow him there.