Tor.com comics blogger Tim Callahan has dedicated the next twelve months to a reread of all of the major Alan Moore comics (and plenty of minor ones as well). Each week he will provide commentary on what he’s been reading. Welcome to the 15th installment.

By now, you know the deal: I’m talking about Alan Moore’s seminal run on Swamp Thing, circa 1984-1987. Two weeks ago, I responded to Alan Moore’s opening few arcs on the series, and last week we read about all kinds of evil, political messaging, and the impending crisis. Or Crisis! As in, Crisis on Infinite Earths, the DC maxi-series that paired the complex multiversal history of the company down to a single Earth, a single reality, and almost-sort-of-kind-of rebooted everything in its wake, mid-1980s-style.

DC history was a flawed contradictory beast, pre-Crisis, and the “streamlined” DCU that followed wasn’t any better, really, even if it seemed that way at the time. A series of other kinds of crises followed over the next couple of decades, from Zero Hour to Infinite Crisis to Final Crisis to the most recent DC reboot in the fall of last year. Perhaps you heard about that?

Anyway, none of this is germane to our discussion of Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing run, except that, as a DC writer, he played along with the party line, and incorporated a crossover issue – and a couple of foreshadowy appearances of Crisis characters like the Monitor and Harbinger – into the larger story he was in the midst of telling. Though by the time he was into year two on the series, he seemed to take his lead from Crisis, rather than merely just play along. He built the cataclysm up to Swamp Thing issue #50, which was something along the lines of what we might retroactively name “Crisis Beyond,” a mystical off-shoot of Crisis proper, expanding the cosmic wave of destruction into a spiritual conflict between two omnipotent forces, with Swamp Thing in the middle and John Constantine sneakily directing traffic.

And that’s where we start this final part of our look at Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing, with the Crisis-build-up and what happens afterward, as Steve Bissette and John Totleben give way to new regular penciller Rick Veitch and the “sophisticated suspense” gives way to “mysteries in space” and sci-fi trappings replace the horror elements until Swampy makes his way home, and they all live – could it be possible – happily ever after?

We will see.

The Saga of the Swamp Thing Book Four (2010)

This hardcover reprint volume collects Swamp Thing #43-50, originally cover-dated December 1985-July 1986. Some may tell you that this is the absolute pinnacle of Moore’s achievement on Swamp Thing, and I think you might want to trust those people, because the stuff in this volume – particularly what happens in the oversized issue #50 – is surely some of the best stuff Moore would ever do on any corporate characters. Me, I’m partial to his first year on the series, when he was changing what comics could be and influencing an entire generation of comic book writers. But, yes, these pre-and-post-Crisis issues are good indeed. Darn good.

It begins with a story that has little to do with the overarching plot, but introduces a character who would become integral to Moore’s Swamp Thing by the end, and even more central to the story that followed Moore’s departure: Chester Williams.

Williams, a red-haired, pony-tailed hippy environmentalist looks a whole lot like one of Nukeface’s main victims from a previous story arc, but in issue #43 that character didn’t fare to well, and Williams survives for years, even amidst the insanity of Swamp Thing‘s world.

Thematically, the opening story in this volume – a story in which Swamp Thing appears only incidentally – deals with faith. Specifically, the notion of Swamp Thing as a kind of god, shedding his tubers in the world, leaving these eco-friendly hallucinogens for the world to find. It’s like the ultimate drug, one that amplifies your consciousness and expands what’s there. If you’re hateful, you’ll see and feel unbearable hate. But if you’re full of love, you’ll get love in return. Spiritually. Chemically.

Chester Williams himself never actually tries the stuff. He’s an apostle who hasn’t tasted the wafer.

The next two issues are also done-in-ones where Swamp Thing, the character, doesn’t hold center stage. The effect is to turn the series, briefly, into a modern-day version of the classic DC horror anthologies, letting stories unfold without particular regard to any one recurring character. In issue #45, Moore (along with Bissette, Totleben, and help from Ron Randall) give us “The Bogeyman,” a serial killer who Neil Gaiman would later elaborate upon for his memorable Corinthian character. Issue #46 provides a haunted house story, using the real-life “Winchester Mystery House” as an inspiration.

The stories are structured almost musically, with repeated refrains to add an ominous echo throughout each, and they are fine, well-told tales. People seem to like them. I prefer others more, so I’ll move on to….

Issue #46, blazoned with the “Special Crisis Cross-Over” label across the top of the cover, with the giant 50th Anniversary DC logo on the left. Hardly a measure of the kind of sophisticated suspense we’d been conditioned to see in the series. And with Hawkman and Batman, and a… dead dinosaur(?) in the cover image, it’s clearly the place where Swamp Thing changed for the worse. If I were ever to use “jumped the shark,” now would be the time – based on how much of a sell-out cover we see here.

Yet, that’s not true at all. This is such a strong issue – such a quintessential installment of Alan Moore’s Swamp Thing – and it proves that crossovers and tie-ins aren’t inherently bad. They have just as much story potential as anything else. It’s all in the execution. Moore, and Steve Bissette and John Totleben, just know how to do it better than most, so we get a Crisis crossover that manages to tell a genuinely creepy and disarming Swamp Thing story and explore the potential of a multiversal catastrophe. While Marv Wolfman and George Perez show what the collision of infinite Earths would look like, with dimensional overlaps and time fractures, Moore, Bissette, and Totleben show us what it would feel like. We inhabit the Crisis here, in a way that’s impossible in the maxi-series itself, which is more concerned with taking inventory of the breadth of the DCU and giving lots of characters the chance to punch other characters beneath the red skies.

John Constantine acts as a tour guide through the insanity in the issue – a role he’s uniquely suited for, and “tour guide through insanity” is a far more interesting job description than punk magician or musty elder statesman of street magic or whatever he has become in the decades since his solo Vertigo series launched – and in a single scene, Alan Moore and his artistic collaborators imbue Crisis‘s whirring plot mechanism, Alexander Luthor, with more life and personality than we see in all twelve issues of the maxi-series.

Plus, we get snapshots of the effects of the Crisis itself, the odd corners of the event, where “A jackboxer from the Manhattan saltbogs of 5070 had managed to bring down a young ichthyosaurus with his whorpoon.” Yes, that!

By the end of the issue, Swamp Thing surveys the Crisis, but doesn’t interact with it, other than a brief trip to the Monitor’s satellite, and Constantine tells him of the Brujeria, the “secret society of male witches that have existed for centuries.” In other hands, the reveal of the big bad as a mere coven of witches (even male ones) would hardly be an appropriately escalating conflict, particularly as an epilogue in a story about colliding worlds and infinite superheroes and good versions of Lex Luthor from another dimension. But Moore makes the Brujeria terrifying, explaining, through Constantine, that they have been behind all the darkness bubbling to Swamp Thing‘s surface. They are behind it all. And their grotesque emissaries, twisted babies grown for horrible violence, are coming.

First, an interlude, as Swamp Thing visits the Parliament of Trees in issue #47, and learns about his place in the larger scheme of the elementals. Short version: he’s not ready yet. They don’t want him. He has more to learn.

Right! Back to the Brujeria with issue #48, penciled and inked by John Totleben, who provides a lush and terrifying final confrontation between our hero, and a savagely battered John Constantine, and the Brujeria. As a single issue—though part of a much larger epic story, connecting the ongoing Constantine subplot through Crisis and into Swamp Thing’s 50th issue – it’s quite a spectacle. Harsh, brutal, with a vicious climax. And Swamp Thing wins, saving Constantine. But the Brujeria have unleased the darkness. The spiritual crisis will only grow. There’s no stopping it.

Unless you’re John Constantine, and you assemble all of DC’s magical heroes into one two-part story that culminates in Swamp Thing #50 where the hand of darkness rises up and reaches for the hand of God. Yes, that happens, and no description of the sequences in the story can do it justice, but when anyone says that this collection of Swamp Thing stories is the best of the bunch, surely they are talking about everything involved in this massive confrontation between darkness and light, and all of the DC oddballs playing their roles. It’s Mento from Doom Patrol and Dr. Occult from the old Action Comics. Deadman and the Spectre, with the Demon clad in living crustacean armor. It’s Dr. Fate and Sargon the Sorcerer

This is the real Crisis, and it hurts.

But in the end, after the near-omnipotent Spectre, hundreds of feet tall, crashes down after failing to stop the rising pillar of darkness, the victory comes through understanding. Through embrace, rather than conflict. Swamp Thing communes with the darkness, understands it, and when the giant hand of darkness reaches up from the depths toward the giant hand from the heavens, they merge, swirl into the yin and the yang.

Constantine calls it a draw, but it’s really about the relationship between good and evil, as the Phantom Stranger conveniently explains to Swamp Thing, and to the reader: “All my existence I have looked from one to the other, fully embracing neither one…never before have I understood how much they depend upon each other.” Then, a sunset.

Neat and tidy wrap-up? Sure, but the costs were enormous – many of DC’s magical heroes sacrificed their lives – and Moore’s lesson seems clear: sometimes, in the fray, victory doesn’t come from who has the strongest armies, but who is willing to work with the other. Who is most willing to understand.

Okay, it is too neat and tidy, but that doesn’t mean it isn’t satisfying. And with that, Moore wraps up his run on Swamp Thing. Wait, what’s that? There are still two more hardcover collections to go? Moore writes the series for 14 more issues? What can he possibly have left to say, or do, with the character? Oh. I see….

The Saga of the Swamp Thing Book Five (2011)

Here we go, the post-Crisis aftermath, with “Home Free” in #51 (August 1986) though the shockingly new direction of “My Blue Heaven” in Swamp Thing #56 (January 1987).

The real fallout from the cataclysmic confrontation between good and evil, or light and dark, or Monitor and Anti-Monitor (can you believe there was once a generation of comics readers who thought “Anti-Monitor” was a cool name for a bad guy? And that generation of comics readers is now the generation in charge of making new comics?) isn’t any notable change to the Swamp Thing continuity. Or even the psychological fallout of an epic battle, resolved. It’s that, while the gods dueled between Heaven and Hell, the real evil could be found in the prejudice on the ground.

I didn’t mention it in my reflection on “Book Four,” but one of the plot threads that emerged for Abby Cable, while her Swamp Thing was off fighting the good fight, was the emergence of a few candid photos of her embracing her vegetable lover. That small little thread becomes the tapestry of the issues in this volume, as Abby finds herself fleeing the law – heading to Gotham – because society cannot accept her relationship with an inhuman monster.

Alan Moore made Abby and Swamp Thing’s love a centerpiece of his run on the series, and in these issues, he deals with the repercussions of that verdant romance. Not everyone would be as accepting of their relationship as comics readers might be.

With Steve Bissette entirely gone from the interiors, and John Totleben returning for just one final (memorable) issue, the look of Swamp Thing becomes both less horrific and less luxurious. The stories in this volume are mostly drawn by Rick Veitch, mostly illustrated by Alfredo Alcala, and they make for an interesting, if different, kind of art team. Veitch, weaned on underground comics, seems able to combine his Joe Kubert schooling with an arch sense of oddness that might have come from the more exotic issues of Mad. Yet Alcala’s scratchy ink line and relentlessly layered blackness gives the rendering an etched quality, as if peeled from some stark gothic novel. Veitch stiffly poses his characters with a fluid line, while Alcala traps them in a chiaroscuro landscape, feathered with rough detail.

It’s a style that works, but it turns the Swamp Thing character from something made of moss and reeds and bog-matter into something more like a green-leather shambling tree. The character seems to become visually rougher, harder, and that only emphasizes his “take no prisoners” approach to the situation he finds himself in. His lover has been taken from him by a society that doesn’t understand the depths of their relationship. And he attacks, not as a lumbering monster, but as a force of nature. As a stake into the heart of the social order.

That’s what Moore and Veitch and Alcala show us in the first couple of stories here, leading toward the inevitable: Swamp Thing vs. Batman. After all, if you go to Gotham, you know what you’ll find there.

The oversized Swamp Thing #53 features John Totleben’s penultimate work on the series, as he pencils and inks Swamp Thing’s assault on Gotham. I’d rank it as the third-best issue of the entire run (after #21, and #50, as the one and two slots, respectively). It weaves much of the Swamp Thing legacy into a single issue, bringing in Chester Williams, the love between Abby and Swamp Thing, the alien strangeness of the superhero archetype, the remnants of the Sunderland Corporation and DDI, the worship of Swamp Thing as a kind of god, violent action, and the death of a featured character.

It’s all here, gorgeously articulated by Totleben.

And the featured character who dies? Swamp Thing himself. Again.

He survives Batman’s defoliant spray (who but Totleben can make weed killer look so poetic and heroic and tragic, all at the same time?) but old man Sunderland gets his revenge from beyond the grave as his minions finally manage to trap and kill Swamp Thing. Disorienting him so he cannot escape his own body and travel through the Green, they blast his mucky form with napalm as Abby watches him burn.

Swamp Thing is dead, as far as Abby knows, as far as any of us know. Unless we have read comic before – specifically Alan Moore comics – where the death of a main character in a series like Swamp Thing means that it’s only a matter of time before a trip to the afterlife brings the person back to the land of the living.

But that’s not what happens here. Swamp Thing stays dead, on Earth at least, and only reappears in the final pages of issue #55, in distant space, on an alien planet far away.

Before his return, dressed in blue vegetation, millions of light years from home, Abby mourns, and Liz Tremayne returns. Tremayne, an investigative journalist from the Marty Pasko days, hadn’t been seen in Alan Moore’s run since the early issues. But she returns in Swamp Thing #54, paralyzed into inaction through the off-panel domineering of Dennis Barclay. It gives Abby something to react to on Earth, while Swamp Thing is, unbeknownst to her, far away, and it helps expand the supporting cast to provide more dramatic opportunities, but the return of Liz Tremayne isn’t as interesting, or genre-bending as what follows. Because Swamp Thing doesn’t just pop up in outer space, on a distant planet. In “My Blue Heaven” in Swamp Thing #56, he recreates his world. He’s the artist, and his canvas is the entire planet.

In the introduction to the collected edition, Steve Bissette notes that the change in direction from horror to sci-fi was caused by Rick Veitch’s own interest in the latter, and because Alan Moore was looking to take the series in a new direction. That’s certainly what happens, starting with “My Blue Heaven” and running right up to Alan Moore’s swan song on the series with issue #64. But I’ll get to the end soon enough. Let’s talk about the beginning of this sci-fi tangent, because it’s as odd and amazing and unconventional as anything in the entire run.

I should confess that “My Blue Heaven” isn’t my favorite issue to reread. The captions can be a bit tedious, and much of the story could have been told merely through imagery, but there’s no mistaking the unusual approach Moore takes in the telling of this tale. For a mainstream monster comic, even one that has pushed those boundaries to the limit and kicked off a cycle of influence that would eventually spawn Vertigo Comics and the imitators that followed, taking an entire issue to show the main character in an alien landcape, pouring his own psychology (and perhaps a bit of the writer’s) into the molded mockery of life on Earth, well, it’s just a stunning spectacle. Drenched in blues and pale greens by colorist Tatjana Wood, “My Blue Heaven” is a visual representation of Swamp Thing confronting his own life – creating a Bizarro version of it, under his control – and then smashing it for its imperfections. Its part a celebration of what the character has become and a commentary on the artist’s relationship to his own art.

The final image on the final page of the story is Swamp Thing (or Blue Alien Thing as he’s never called), morphing away into the space-Green, disappearing into the stars, as the decapitated head of his Blue Abby (constructed from flowers) lies in the foreground, a token of his lost love.

A quick note, before moving on to the grand finale, before the last Swamp Thing volume where everything comes to an end: in Watchmen, which I will start talking about in a couple of weeks, there’s a now-famous sequence with Dr. Manhattan on Mars, reconstructing pieces of his world. Alan Moore did that shtick in Swamp Thing months before he did it in Watchmen. “My Blue Heaven” may not be the birth of what would latter happen with Dr. Manhattan, but they are definitely related.

The Saga of the Swamp Thing Book Six (2011)

I feel I’ve gone on too long. This is a relaxed marathon, not a race to the finish line, but as we approach the final volume, I will do my best to pick up the pace. And the stories collected here make it easy to do just that. These aren’t packed with the density of what came before. Alan Moore wrote worthwhile stories up until the very end, but there’s a briskness to these – perhaps because of their sci-fi trappings – that make them quicker to read, and quicker to discuss, than the ones that filled the bulk of his run on Swamp Thing.

It’s Swamp Thing’s space adventures, bopping around the DC sci-fi landscape instead of its mystical one, and Moore provides a definitive take on Adam Strange, as well as a humanized approach to the Fourth World.

The two-parter that kicks off this volume, from 1987’s Swamp Thing #57-58, spotlights Silver Age space adventurer Adam Strange, Zeta Beam rider and protector of Rann. The story pits Strange vs. Swamp Thing at first (after all, he still looks like a monster, even using Rannian vegetation), but it later reveals itself to be a story about fertility and life. Swamp Thing uses his power to save the barren Rann, even with Thanagarian meddling to deal with. Moore choses to keep all the Rannian dialogue indecipherable, which puts almost all of the storytelling weight on Rick Veitch and Alfredo Alcala, but they completely handle the burden. It’s a fine tale, one that would inspire a later Adam Strange miniseries that would pick up on some of the threads from this story, but completely lack the compelling sensibility that makes this version so engaging.

Moore is absent from #59, other than as a general “plot” assist, with Steve Bissette coming in to write, but not draw, a story about Abby’s “Patchwork Man” father. But this isn’t called “The Great Steve Bissette Reread,” is it? (That is still a few years away, at best.)

Issue #59 gives us “Loving the Alien,” John Totleben’s final issue, done as a series of collages. The typeset text is layered over bits of machinery and photocopied illustrations and who-knows-what-else. Reportedly, the collage images were stunning to behold in real life. Printed on the page, they look terrible. And the cryptic caption boxes detail a battle between Swamp Thing and a techno-alien life force, but the whole thing is completely skippable. Maybe there’s something here worth delving deeper into, but I haven’t found it, in all my rereads of this issue. It’s a noble experiment, gone completely astray.

Swamp Thing#61-62 are a return to form as Moore, Veitch, and Alcala provide back-to-back explorations of some of DC’s most fascinating characters: the alien Green Lanterns and the New Gods. Where would an exiled-from-Earth nature-hopping life-form go in deep space? If you’re a long time Green Lantern fan, there’s only one other vegetable-based life form who comes to mind: Medphyl, the Green Lantern who looks like a humanoid carrot, first introduced to the DCU all the way back in 1962. The touching Medphyl story (where Swamp Thing inhabits the recently-dead body of Medphyl’s mentor, and provides closure to the galactic space ranger) leads into the amazingly dense and expansive “Wavelength” where Jack Kirby creations smash up again the Len Wein/Bernie Wrightson muck monster, just like the good old days of “Volume One.”

“Wavelength” largely focuses on Metron and Swamp Thing set against the cosmic backdrop of the Source Wall. Metron peers into the Source, and narrates his findings. What he sees, drawn on the page, appears as several 25-panel pages, pulls Kirby history into Swamp Thing’s history into the history of the real world. Everything is compressed into those tiny panels, from the Big Bang through Ragnarok, from the Crisis to Borges to Sandman to Hitler, leading up to a splash page of Darkseid’s immense stone face, laughing at what Metron describes.

Moore gets a little sappy at the end, but fittingly so, given the larger context of his Swamp Thing run. Darkseid provides a soliloquy to wrap up issue #62: “You [Swamp Thing] have exposed one of the most painful roots of madness…and thus added and essential element to the Anti-Life Equation. An element that had escaped me until now…one which Darkseid was not capable of anticipating. Love.”

Awww.

And with that, thanks to some help along the way, Swamp Thing zooms back to Earth for the final two issue of Alan Moore’s run, emerging from the ground on the last page of issue #63 to hold Abby in his arms once again.

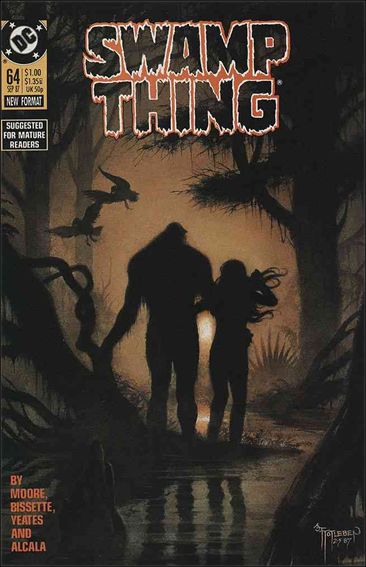

Alan Moore’s final issue, Swamp Thing #64 (a.k.a. the very first Alan Moore Swamp Thing I ever read) is probably the worst place to start reading Swamp Thing. Tonally, it’s not like the rest of his run, and it doesn’t even have the horror or sci-fi texture which make his run so compelling from beginning to end (assuming, that is, that you skip or skim the collage issue). “Return of the Good Gumbo” in issue #64 brings back original Saga of the Swamp Thing artist Tom Yates, along with a few pages of art from Steve Bissette and regular series artists Rick Veitch and John Totleben. It’s an epilogue issue, no grand catalysms here. The wars have already been fought and won (or drawn), and the grand hero has returned from his space odyssey to recapture the heart of his beloved.

We get recaps of some of that here, as we see Swamp Thing and Abby frolic together and prepare their new dream home – a literal tree house, apparently informed by the alien landscapes Swamp Thing has visited.

The issue is bookended by some narrative bits about Gene LaBostrie, the Cajun fisherman, the gumbo-maker. He pushes his skiff through the swamp, watching the two lovers enjoy being together. Enjoying the sunshine and the deep happiness that comes after such great tragedies and such powerful love.

Gene LaBostrie, tall and bearded, looks familiar. He’s the visage of Alan Moore himself, waving one final farewell to the characters he guided for almost four years. Alan Moore, saying goodbye.

NEXT: There’s that one other Alan Moore Swamp Thing story I didn’t write about yet. Featuring Superman!

Tim Callahan writes about comics for Tor.com, Comic Book Resources, and Back Issue magazine. Follow him on Twitter.