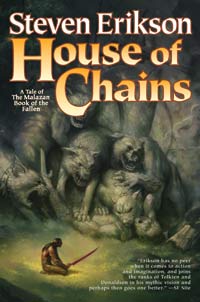

Welcome to the Malazan Re-read of the Fallen! Every post will start off with a summary of events, followed by reaction and commentary by your hosts Bill and Amanda (with Amanda, new to the series, going first), and finally comments from Tor.com readers. In this article, we’ll cover Chapter Twenty-Three of House of Chains by Steven Erikson (HoC).

A fair warning before we get started: We’ll be discussing both novel and whole-series themes, narrative arcs that run across the entire series, and foreshadowing. Note: The summary of events will be free of major spoilers and we’re going to try keeping the reader comments the same. A spoiler thread has been set up for outright Malazan spoiler discussion.

Chapter Twenty-Three

SCENE ONE

Mogora “cooks” for Apsalar and Cutter while complaining about Pust’s absence, the lack of real food around, etc. Before leaving, she mentions Kalam was there earlier, which surprised Cutter but not Apsalar (Kalam had left Bridgeburner marks). Apsalar says “Shadowthrone and Cotillion have it seems found use for us all. If I were to guess, Kalam plans on killing as many of Sha’ik’s officers as he can.” Cutter wonders what they’re doing there and Apsalar says she doesn’t know, but believes Cotillion is interested more in Cutter than her because she is “not interested in becoming his servant. I possess too many of his memories, including his mortal life as Dancer, to be entirely trustworthy.” Pust arrives and tells them they’re mad for eating Mogora’s cooking. Cutter tells Pust Mogora is happier without him and calls him “useless,” which makes Pust vanish back into the shadows. Apsalar warns him it isn’t smart to get between a husband and wife. Cutters asks her where she wants to go and when she says she hasn’t decided yet, he can tell she really has.

SCENE TWO

Trull thanks Ibra Gholan for the spear he has just given him. He tells Onrack he’s ready though he wishes they had some furs as the warren is cold. Onrack tells him they’ll travel in a few days from tundra to savanna to jungle. When Trull asks if he thinks they’ll beat the renegades to the First Throne, Onrack answers he thinks so as Tellann will be easy for their group but the path of chaos, which is “never straight” will slow the renegades. He adds that when they reach the Throne, they’ll have to defend it. Ibra and Monok frame Trull and Onrack on the march, indicating their continued distrust of them. Onrack and Trull agree that while they’re needed now, they’ll have to keep a sharp eye out when they no longer are. They move through tundra then marsh then bedrock then forest before stopping. When Ibra asks why, Onrack says it’s so Trull can rest, or has Ibra forgotten mortals need to. When Ibra says he hasn’t forgotten, Trull says, “It’s called indifference, Onrack. I am, after all, the least valuable member of this war party.” Monok asks Trull why the Edur have bowed before the Chained God. Ibra heads off to hunt as Trull begins to answer, beginning by saying he’s not the best taleteller as he is “Shorn. I no longer exist. To my brothers and my people, I never existed.” Onrack calls that “meaningless in the face of truth” and Monok says although the T’lan Imass have exiled their kind, “we still speak of them. We must speak of them, to give warning to others. What value a tale of it is not instructive?” Trull answers that is an “enlightened view But mine are not an enlightened people we care nothing for instruction. Nor, indeed, for truth. Our tales exist to give grandeur to the mundane. Or to give moments of great drama and significant and air of inevitability . . . Every defeat justifies future victory. Every victory is propitious. The Tiste Edur make no misstep, for our dance is one of destiny.” When he claims he was never in that dance, due to being shorn, Onrack says the exile has forced Trull to lie even to himself, to which Trull replies, “That is true. I am therefore forced to reshape the tale . . . There was much of that time that I did not understand at first—certainly not when it occurred. Much of my knowledge did not come to me until much later.” Onrack interrupts to say it happened after Trull’s shorning, and when Trull agrees, Onrack thinks, “As knowledge flowered before my mind’s eye in the wake of the Ritual of Tellann’s shattering.” Out loud he tells Trull to continue, and “if instruction can be found within [your tale] recognition is the responsibility of those to whom the tale is told. You are absolved of the necessity.” Monok, however, objects, arguing, “These words are spurious. Every story instructs. The teller ignores this truth at peril.” Trull says he will tell the tale of the Tiste Edur who lived north of Lether, save the one exception that he will tell it without “aggrandizement . . . reveling in glory . . . [or] claims of destiny or inevitability.” He says he’ll try to be “other than the Tiste Edur I appear to be, to tear away my cultural identity,” and when Monok interrupts to say “flesh does not lie . . . thus we are not deceived,” Trull responds “but the spirit can, Bonecaster. Instruct yourself in blindness and indifference—I in turn intend to attempt the same.” Monok wants to know when Trull will start telling his story, and Trull says at the Throne while they await the renegades and Edur. Ibra Gholan returns with a hare for Trull. Onrack is bothered by Trull’s words, bothered by the spiritual, emotional scarring Onrack hadn’t noticed beneath Trull’s outward steadiness and his physical scars left by the Shorning. He thinks Trull is “born of scars, of healing that left one insensate. His heart was incomplete. He is as a T’lan Imass . . . We ask that he resurrect his memories of life, then wonder at his struggle to satisfy our demands. The failure is ours, not his. We speak of those we have exiled, yet not to warn as Monok Ochen claims . . . We speak of them in reaffirmation of our judgment. But it is our intransigence that finds itself that finds itself fighting the fiercest war—with time itself, with the changing world around us.” Trull says when he begins, he will start with an observation about “nature and the exigency of maintaining a balance,” a statement that gives Onrack a chill. Trull continues: “Pressures and forces are ever in opposition. .. And the striving is ever towards a balance. This is beyond the gods, of course—it is the current of existence—but no, beyond even that, for existence itself is opposed by oblivion. It is a struggle that encompasses all, that defines every island in the Abyss . . . Life is answered by death. Dark by light. Overwhelming success by catastrophic failure. Horrific curse by breathtaking blessing. It seems the inclination of all people to lose sight of that truth.” He offers his small cookfire as an analogy, saying it serves his delight, but if he doesn’t put it out, “igniting this entire world will also kill everything in it, if not in flames, then in subsequent starvation.” Monok says he doesn’t see the point, and that “this prefaces nothing.” But Onrack says otherwise—”It prefaces everything”—support which Trull answers “with a smile. Of sadness overwhelming. Of utter despair. And the undead warrior was shaken.”

SCENE THREE

Lostara and Pearl continue into the desert, believing the fall of the Whirlwind means Tavore’s army had entered Raraku and were marching toward the oasis. Pearl senses “the goddess had drawn inward, concentrating her power for perhaps one final, explosive release. For the clash with the Adjunct. A singularity of purpose locked in rage, a flaw that could be exploited.” As for their “relationship,” Lostara thinks now that they’ve taken care of “long pent-up energies” they could move on, but Pearl appears to think differently and when he tried taking her by the hand, she clearly rejected the idea. They stop one ridge removed they think from the oasis. Pearl says he’s thinking of infiltrating the camps and causing trouble. Plus, he thinks the master of the Talons is in the camp, adding he now believes “the rebellion was compromised long ago, perhaps from the very start. The aim of winning independence . . . was not quite as central to some as it should have been . . . those hidden motives are about to be revealed. As he speaks, Lostara notes “an object lying among the cobbles—a momentary recognition, then her gaze quickly shifted away.” She asks Pearl if he’s considered he might be screwing up missions already in place, seeing as how neither the Empress nor Tavore know of his presence there. As he answers, she surreptitiously picks up the object. They continue on, walking over ground “littered with the tiny, shriveled bodies of countless desert creatures that had been swept up into the Whirlwind . . . They had rained down for a full day.” Pearl notes, “the Whirlwind has not been friendly to Raraku,” to which Lostara replies, “Assuming the desert cares one way or another, which it doesn’t, I doubt it will make much difference in the long run. A land’s lifetime is far vaster than anything with which we are familiar. .. Besides, Raraku is already mostly dead.” Pearl tries to argue otherwise, saying, “Appearances deceive. There are deep spirits in this Holy Desert,” but Lostar says he’s foolish to think the spirits care anything about the life atop the desert. He tells her she should respect the “mysteries of Raraku.” Pearl complains to Lostara that she seems to always create “discord.” Lostara answer that he thinks too much, saying she thinks “neither too much nor too little. I am perfectly balanced—this is what you find so attractive.” She says he’s like a capemoth drawn to the flame, and when he asks if she’s supposedly pushing him away for his own good, she says “fires neither push nor pull. They simply exist, compassionless, indifferent . . . That is another one of your flaws, Pearl. Attributing emotion where none exists.” She tells him to give it up, but when he says he’ll take her advice, she then tells him “gullibility is a most unattractive flaw,” which brings him close to explosion. As they near the final ridge, he asks her what she picked up and put in her pouch. She tosses it to the ground and tells him to look, but when he bends to do so she knocks him out. She picks him up and carries him down the slope (the oasis is only 2000 paces away), hiding when a group of desert warriors rides by, she recognizes them as Ashok Regiment, which she’d thought had been totally wiped out. When dusk falls, Cotillion comes out of the shadows. Lostara, who mentions that Cotillion had “recruited her” tells him Pearl was about to interfere and she knocked him out figuring that Cotillion wanted the path clear. But Cotillion says he thinks Pearl might actually be useful and tells her to make sure he’s awake tomorrow night. Just before he leaves to attend to “other tasks,” she tosses him the object she had picked up, saying she “assumed” it was his. Cotillion says it isn’t, but he knows who it does belong to and he is “pleased.” He asks if he can keep it and she says it doesn’t matter to her, but the way he tells her “Nor should it Lostara Yil,” makes her think “she had made a mistake in letting him keep the object; that, indeed it did matter to her, though for the present she not how.” Cotillion leaves.

SCENE FOUR (Lots of quoting in this one…)

Apsalar looks out a window of Pust’s temple: “She had never felt so alone, nor she realized so comfortable with that solitude. Changes had come to her. Hardened layers sheathing her soul had softened, found new shape in response to unseen pressures from within. Strangest of all, she had come, over time, to despise her competence, her deadly skills. They had been imposed upon her, forced into her bones and muscles. They had imprisoned her in blinding, gelid armor. And so, despite the god’s absence, she still felt as if she was two women, not one. Leading her to wonder with which woman Crokus had fallen in love. But no, there was no mystery there. He had assumed the guise of a killer . . . a dire reflection—not of Apsalar the fisher-girl, but of Apsalar the assassin, the cold murderer. In the belief that likeness would forge the deepest bond of all. Perhaps that would have succeeded, had she liked her profession . . . had it not felt like chains wrapped tight about her soul. She was not comforted by company within her prison. His love was for the wrong woman. . . And hers was for Crokus, not Cutter. And so they were together, yet apart, intimate yet strangers, and it seemed there was nothing they could do about it.” She thinks that the fisher-girl could not stand against the will of the assassin, just as Crokus “had similarly succumbed to Cutter.” Cotillion joins her and she tells him “would that you had taken all with you when you departed.” When he asks if she’d prefer he’d left her “bereft,” she says “No, innocent.” Cotillion tells her “Innocence is only a virtue, lass, when it is temporary. You must pass from it to look back and recognize its unsullied purity. To remain innocent is to twist beneath invisible and unfathomable forces all your life, until one day you realize that you no longer recognize yourself, and it comes to you that innocence was a curse that had shackled you, stunted you, defeated your every expression of living.” Apsalar replies, “But Cotillion, it is knowledge that makes one aware of his or her own chains.” Cotillion tells her “Knowledge only makes the eyes see what is there all along.” He adds she cannot “unmake yourself”, but she says she can choose to stop walking this particular path. He also tells her that he “walked in your bones, your flesh . . The fisher girl who became a women—we stood in each other’s shadow . . . It was difficult to remain mindful of my purpose. We were in worthy company . . . [Whiskeyjack’s] squad would have welcomed you. But I prevented them . . . Necessary, but not fair to you or them.” He tells her he needs to know her decision about Cutter and she says she doesn’t want Cotillion to do to Cutter what he did to her, he’s that important to “the fisher-girl whom he does not love . . . He loves the assassin and so chooses to be like her.” Cotillion says he now understands her struggle, but she’s wrong, Cutter is attracted to the assassin but does not lover her; he’s attracted to the power and ability to choose not to use power: “He is drawn to emulate what he sees as your hard-won freedom.” He tells her Cutter’s love didn’t come when she was Sorry, but after Cotillion had stopped possessing her. When Apsalar objects that love changes, Cotillion says it does, then makes a poor analogy with a capemoth, then tells her love “grows to encompass as much of the subject as possible. Virtues, flaws, limitations, everything—love will fondle them all, with child-like fascination.” When she begins to refer to the two women inside her, he tells her there are “multitudes, lass, and Cutter loves them all.” She says she doesn’t want Cutter to die and when he asks if that’s her decision, she says yes, though she knows what she must do. Cotillion tells her he is pleased, and when she asks why he says because he likes Cutter too. She inquires how brave he thinks she is and he responds “as brave as necessary.” She replies “again,” and he says “Yes, again.” She tells him he doesn’t seem much like a god and he tells her “I’m not a god in the traditional fashion. I’m a patron. Patrons have responsibilities. Granted, I rarely have the opportunity to exercise them.” She comments that he means, “they are not yet burdensome,” which evokes “a lovely smile.” He tells her she’s “worth far more for your lack of innocence,” and prepares to leave. Apsalar thanks him and asks him to take care of Cutter. He answers he will, “as if he were my own son.” He leaves, then soon afterward she does as well.

SCENE FIVE

Kalam hides in the petrified forest, surrounded by snakes. He senses a power, a presence in the forest, one that did not “belong on this world,” something “demonic.” He examines his otataral knife, thinking how few knew its full properties, or how its effects were unpredictable and varied if absorbed through the skin or via breathing it in. He also recalls a discovery made by accident, one which only a few survived, including him and Quick Ben—the discovery that otataral has a violent reaction to heat and to Moranth munitions: “But even that was not the whole secret. It’s what happens to hot otataral when you throw magic at it.” As he examines his other blade, an acorn drops down next to him. He looks up at the tree over him and says “Ah, an oak. Let it not be said I don’t appreciate the humor of the gesture . . . Just like old times, glad as always, that we don’t do this sort of thing anymore.”

SCENE SIX

Onrack and the others reach the jungle and begin to follow a game trail. Trull notes this probably isn’t the T’lan Imass’ nature territory and Onrack says he’s right; “We are a cold weather people. But this region exists within our memories. Before the Imass, there as another people, older, wilder. They dwelt where it was warm, and they were tall, their dark skins covered in fair hair. These we knew as the Eres. Enclaves survived into our time—the time captured within this warren . . . [They lived on] surrounding savannas. They worked in stone, but with less skill than us.” Monok adds, “All Eres were bonecasters for they were the first to carry the spark of awareness, the first so gifted by the spirits.” When Trull asks if they are gone, Monok says yes. Onrack says nothing, but thinks, “If Monok Ochem found reasons to deceive, Onrack could find none to contradict the bonecaster.” Trull changes the subject to ask if they’re close and if they’ll return to their own world if so. Onrack says yes, and begins to explain the First Throne lies at the “base of a crevasse beneath a city,” but Monok interrupts to say Trull needn’t know the name; he already knows too much. Trull says what he’s learned of the T’lan Imass isn’t particularly a secret: “You prefer killing to negotiation. You do not hesitate to murder gods when the opportunity arises. And you prefer to clean up your own messes . . . Unfortunately, this particular mess is too big, though I suspect you are still too proud to admit that.” He continues by saying besides, he’s not likely to survive the upcoming fight and in any case Monok will probably try to ensure that. Monok doesn’t disagree, and Onrack thinks he will try to defend Trull, anticipating that Monok and Ibra, knowing that, will probably try to take Onrack out first. The trail opens up to a clearing filled with bones and rotting flesh and flies. Monok explains, “The Eres did not fashion holy sites of their own . . . but they understood that there were places where death gathered, where life was naught but memories, drifting lost and bemused. And so such places they would often bring their own dead. Power gathers in layers—this is the birthplace of the sacred.” Trull asks if the Imass made this a gate then and when Monok answers yes, Onrack criticizes him for giving the T’lan Imass too much credit, telling Trull “Eres holy sites burned through the barriers of Tellann. They are too old to be resisted.” Trull wants to know if the Eres sites belong to Hood, since they’re connected to death, but Onrack tells him Hood didn’t yet exist when the sites were created, nor are the sites death-aspected: “Their power comes . . . from layers. Stone shaped into tools and weapons. Air shaped by throats. Minds that discovered, faint as flickering fires in the sky, the recognition of oblivion, of an end, to life, to love. Eyes that witnessed the struggle to survive and saw with wonder its inevitable failure. To know and understand that we all must die, Trull Sengar, is not to worship death. To know and to understand is itself magic, for it made us stand tall.” Trull points out that if that’s true, then the Imass have “broken the oldest laws of all, with your Vow.” Onrack tells him he is right, though his kin wouldn’t say so: “We are the first lawbreakers, and that we have survived his long is fit punishment. And so it remains our hope that the Summoner will grant us absolution.” Trull says, “Faith is a dangerous thing.” As they begin to use the gate, Onrack sees a tall, figure standing nearby, “with a fine umber-hued pelt and long, shaggy hair . . . A woman. Her breasts were large and pendulous, her hips wide and full.” He sees her move toward Trull, then all goes dark and he hears Trull shout. Before he can reach him, though, they travel. In their own realm again, he sees Trull lying unconscious, “blood smearing his lap . . . it did not belong to Trull Sengar, but to the Eres woman who had taken his seed. His first seed.” He looks more closely and see the blood is from “the fresh wound of scarification beneath [Trull’s] belly button. Three parallel cuts, drawn across diagonally, and the stained imprints of three more, likely those the woman had cut across her own belly.” Onrack asks Monok why the Eres took Trull’s seed and Monok answers he doesn’t know. When he starts to say the Eres are like beasts, Onrack points out this one had “intent” and Monok is forced to agree. He asks why Trull is still passed out and Onrack tells him Trull’s mind is “elsewhere . . . I came into contact with sorcery. That which the Eres projected . . . It was a warren, barely formed, on the very edge of oblivion. It was . . . like the Eres themselves. A glimmer of light behind the eyes.” They’re interrupted by Apt with Panek riding her, followed by a score of others. Panek asks if this group was all Logros could spare. Monok ignores the question and tells them they aren’t welcome, to which Panek replies “too bad, for we are here. To guard the First Throne.” Onrack asks who they are and who sent them and Panek identifies himself but says he can’t answer the second question. He adds he guards the outer ward, but the chamber “that is home to the First Throne possesses an inner warden—the one who commands us. Perhaps she can answer you.” They head that way.

Bill’s Reaction to Chapter Twenty-Three

After the quickening pace of the previous chapters, the somewhat depressing (though ultimately resolved) storyline of Gamet’s state of mine, the rising tension as battle nears, the move into comedy via Mogora is a nice balancing act to give us a bit of a breather. She has some classic lines in here. And does anyone really imagine she and Pust living in “domestic normality?”

Along with the comedy, it’s an interesting if twisted bit of parallel between the beginning, middle, and end of this chapter, with a focus in all three places on a relationship: Pust-Mogora, Pearl-Lostara, Cutter-Apsalar. What’s funny (or sad) is that Pust-Mogora seem to have the best relationship of the three.

Onrack calling a halt to the group’s march to the First Throne is a nice little bit of characterization as he shows some compassion for Trull’s weariness, and also of his kin, who show, in Trull’s words, “indifference” toward his exhaustion—a word that we’ve already seen is loaded with negative connotation in the Malazan universe. The twin poles—compassion and indifference—Onrack free of the Vow displays the former; Monok and Ibra still chained by the vow display the latter. One could also argue Ibra displays lack of curiosity as well by the way he just leaves when Monok starts to question Trull about the Edur’s relationship to the Chained God.

We will meet the Edur in much, much more detail once we get Trull’s story as its own book rather than as a sketchy reference to a tale he’ll eventually tell. His description of them therefore is a nice general introduction to what is to come, a paving of the path so to speak. The details, I’d say, are less important here than the big picture that is being painted of his people and the events that led to his shorning.

When Trull speaks of his people tales, that exist “to give grandeur to the mundane . . . to give moments of great drama and significance an air of inevitability . . . Every defeat justifies future victory . . . ,” I wonder if this is any or so different from those national myths countries tell themselves. If not, then what is does it say that these tale-tellers are “not an enlightened people.”

It’s hard as well not the hear the author in the discussion on stories. Do all stories instruct? Can an author truly “tear away [his or her] cultural identity and so cleanse the tale”? Is it the author’s responsibility or is such “recognition the responsibility of those to whom the tale is told”? (My own belief? Yes—but not necessarily in the way the author might intend; No—we are who we are, though one of our grand capabilities is the ability to place ourselves in another’s skin, though we can’t fully shed our own; No—but only because I don’t like the word “responsibility” in terms of the reader, though I do think the reader will take what they take out of a story, whether it’s “there” or not.)

Speaking of putting ourselves into one another’s skin, after we see Onrack perform an act of compassion by stopping so Trull can rest, we see him here perform an act of empathy, realizing that Trull bears scars and that his outward calm was born of “a healing that left one insensate.” And after all we’ve now seen with regard to the T’lan Imass, how tragic a commentary is it for one to be labeled “a T’lan Imass clothed in mortal flesh”?

“Balance” is another running theme throughout the series and we’ve seen it placed in the mouths of several characters already. Here Trull says it underlies all, even existence itself, since existence itself is “opposed by oblivion.” And we once again see how the Vow blinds as Monok see this as “prefacing nothing” while Onrack sees it as prefacing “everything.”

“There are deep spirits in this Holy Desert”—we’ve seen this already, but file it anyway.

Ashok Regiment prisoners—file.

Another nice touch of, umm, balance with the humor of the banter between Lostara and Pearl, closing with the priceless “Idiot,” coming after the philosophy heavy and dolorous tone of the Onrack/Trull section.

I quoted a lot of the Apsalar-Cotillion scene because so much was in there I thought. The interior monologue of Apsalar is so moving—the way she hates what was done to her, the way she was shaped unwillingly into a killing machine, the way that shaping had walled her off, “hardened her soul,” “imprisoned her in . . . armor” (an echo of something we haven’t heard in a while, this idea of “armor”—recall earlier characters, such as Whiskeyjack, also feeling encased in armor, feeling cut off from humanity—others’ and their own). The way it, in keeping with the book’s prime motif, “chained” her. The way she grieves over losing Cutter to another woman, and that other woman being her other self, her younger self, her truer self, the self she’d rather be. Cutter, she thinks, loves Sorry. And Apsalar loves Crokus. A lot of people complain about the multiple names so often used by Erikson, but here I think we see a wonderfully poignant employment of said names. How Apsalar offer up a trio of lines, each of them heartbreaking on their own, but in concert?: “They were together, yet apart”/”The former could not afford to love”/”the latter knew she had never been loved”.

From such sorrow we move into a philosophy of life, thanks ironically enough to Dancer—a killer supreme. “Innocence is only a virtue when it is temporary . . . To remain innocent is to twist beneath invisible and unfathomable forces . . . until one day you realize that you no longer recognize yourself and it comes to you that innocence was a curse that had shackled [that motif again] you, stunted you.” We bemoan loss of innocence, but Cotillion tells us instead we should celebrate its passage even as we honor its “unsullied purity.” Just because it’s in Cotillion’s mouth, of course, doesn’t make it truth, but personally I’m with Cotillion on this one (though to be honest, I’m quite often with Cotillion), bittersweet as it is. It would also seem to fit the conceptual framework of balance—Innocence on one side, knowledge on the other. Light and Dark.

Beyond his philosophy, I just simply like Cotillion. Always have. Always will throughout this series. He is quite possibly my favorite character in this series, with maybe only Fiddler giving him a run at the title. I love his use of “lass.” His smile. His silences. I like that walking in Apsalar’s flesh was a two-way street (we’ll see this again, by the way). I like that “regrets, I’ve had a few (cue music)” I like that he sighs. I like that he says he “understands the struggle within” Apsalar—and that I believe him: empathy from a god. I like that he tells Apsalar she is wrong about whom Cutter loves. I love his clumsy simile of love being like a “capemoth flitting from corpse to corpse on a battlefield”. Really really love that clumsy simile. I love that he is a god discussing love. I love, really love, his line to Apsalar “there are multitudes, lass, and Cutter loves them all.” I like his “calm, soft eyes”, that he has “lines” and scars. I love that he doesn’t “seem much like a god” nor cares to. I like that he believes in responsibilities (Karsa would like this—recall him upbraiding the Seven for not having any sense of responsibility). I love that he tells Apsalar her worth. That he promises to take care of Cutter as if he were his own son, and that again, I believe him. This is just a lovely scene, coming after tension and humor and before bloodshed. A quiet, still scene full of soft understated emotion (note Apsalar blinking away tears. Apsalar). A scene whose silences and soft tones echo. One of the most moving scenes in the series and moving without all the usual props of death or dying or blood or last farewells. I love this scene.

Otataral and munitions, otataral and heat, otataral and magic. Perhaps we get this little mini-lesson for a reason….

“Her eyes lit on an object lying among the cobbles—a momentary recognition”.

And then…

“Lostara reached into the pouch and tossed a small object towards him [Cotillion].

‘I assumed that was yours,’ she said.

‘No, but I know to whom it belongs.'”

And then?

“Something struck the ground beside him . . . Kalam stared at the small object . . . He sat up and reached down to collect the acorn . . . ‘Just like old times, glad as always, that we don’t do this sort of thing anymore.'”

I’m just going to say file here. But this one’s ripe for some discussion down the road.

We’ve talked of layers before, how that is yet another of the motifs that runs throughout the series and one obviously applicable to our own lives. After all, be build cities atop of cities atop of cities. This is why archaeologists have a Troy I, Troy II, etc. for instance. We build our gods and mythologies atop earlier ones (see the flood/ark story). We build our religious celebrations on earlier ones (see Christianity coopting pagan days, save for that stubborn Halloween that just refused to die, appropriately enough, I guess). So the discussion of the Eres lying below the Imass is yet another example of this. These first with the spark creatures—”the spark of awareness”. Note the fire imagery associated with this. “Fire is life.” (reminds me of The Road: “Do we carry the fire?”). We’ll talk much, much more about the Eres and that mysterious figure that steal’s Trull’s seed (and what she does with it). So obviously file this. But for now, we can fit them into that layering motif. And as well roughly place them in the evolutionary scheme as well: Eres then Imass then humans. Whether these are direct descendants or offshoots (tree versus bush) is still a question. But again, I just enjoy this scale of time and the anthropological underpinnings of so much of this story.

In that vein, I like as well the speculation that the sacred may have grown out of physical sites connected to death. And then the further speculation on what that spark of awareness might entail: “Minds that discovered, faint as flickering fires in the sky [fire imagery again], the recognition of oblivion, of an end, to life, to love . . . to know and to understand that we all must die.” And I love how that is framed via “wonder” rather than fear. And how love plays subtlety into it.

I really like Apt and Panek, but this appearance doesn’t bring happiness. Just the opposite. Take that as fair warning Amanda.

Kalam is on the scene. Pearl and Lostara are on the scene. Tavore and her army are on the scene. Cotillion is on the scene. Sha’ik, Dom, Reloe, Bidithal, Heboric, etc. are on the scene. Karsa is pulling on his trousers as he hops from the changing room towards the stage. The music (the Bridgeburner song) is rising. The curtain is soon to be drawn….

Bill Capossere writes short stories and essays, plays ultimate frisbee, teaches as an adjunct English instructor at several local colleges, and writes SF/F reviews for fantasyliterature.com.