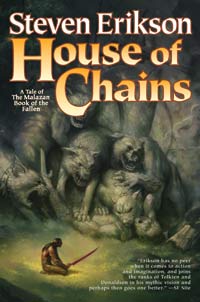

Welcome to the Malazan Re-read of the Fallen! Every post will start off with a summary of events, followed by reaction and commentary by your hosts Bill and Amanda (with Amanda, new to the series, going first), and finally comments from Tor.com readers. In this article, we’ll cover Chapter Eighteen of House of Chains by Steven Erikson (HoC).

A fair warning before we get started: We’ll be discussing both novel and whole-series themes, narrative arcs that run across the entire series, and foreshadowing. Note: The summary of events will be free of major spoilers and we’re going to try keeping the reader comments the same. A spoiler thread has been set up for outright Malazan spoiler discussion.

Chapter Eighteen

SCENE ONE

A memory belonging to Felisin of Tavore recreating with Paran’s toy bone and antler toy soldiers a classic battle when the Royal Untan army defeated the rebellious House of K’azz D’Avore. Tavore had taken on the role of D’Avore and was working through every possible way to attempt victory, though military scholars had long thought it impossible. Felisin never learned if Tavore had succeeded. She remembers Tavore as never really being a child, never really playing: “She had stepped into their brother’s shadow and sought only to remain there, and when Ganoes went off for schooling . . It was as if she had become his shadow, severed and haunting.”

SCENE TWO

Sha’ik looks out over the edge of the ruined city, where the harbor had once been, and now, where rise the remains of coral islands, ramps of hardened sand, a salt flat, bordering dunes. She imagines the placement of her army here where they will meet the Fourteenth, or so Dom plans. She thinks Tavore will once again be playing the role of D’Avore. Mathok stands nearby, her protector now that Karsa and Leoman are gone, though she doubts she needs one as far as Tavore as concerned: “The Whirlwind Goddess could not be breached undetected. Even a Hand of the Claw could not pass unnoticed . . . no matter what warren they sought to employ. Because the barrier itself defines a warren. The warren that lies like an unseen skin over the Holy Desert. This usurped fragment is a fragment no longer, but whole unto itself. And its power grows. Until one day, soon, it will demand its own place in the Deck of Dragons. As with the House of Chains, a new House, of the Whirlwind. Fed by the spilled blood of a slain army.” She imagines what then, with Tavore bent before her in surrender, “her legions a ruin behind her . . . shall I then remove my war helm? Reveal to her at that moment my face? We have taken this war . . . We have supplanted, you and I Tavore, Dryjhna . . . .for our own private apocalypse . . . . when I show myself to you. . . at that moment you will understand. What has happened. What I have done. And why I have done it.” She thinks executing Tavore would be too easy, that survival is the sentence, “staggering beneath the chains of knowledge, a sentence of not just living but living with.” She is joined by L’oric, whom she knows is not simply a mortal man as he is so able to completely hide from her and the goddess. She tells him Heboric has stayed in his tent refusing to see anyone for weeks now and notes L’oric was the last to speak to him, a fact which surprises L’oric. His reaction tell her Heboric’s actions have nothing then to do with whatever he and L’oric had discussed. In reply to her question as to why Heboric might be distressed, L’oric tells her he “grieves for your sacrifice,” which Sha’ik says she finds strange as he never thought much of her as Felisin. She asks which sacrifice in particular he mourns and L’oric says she’ll have to ask Heboric. She changes to subject to Korbolo Dom’s happiness with the battle setting. L’oric says that makes sense as Dom thinks he can make Tavore go where he wants as if Tavore were stupid, but L’oric wonders why Tavore would fight where Dom wants her to, adding there is “danger in trusting to a commander who wars with the aim of slaughter . . . [rather than] victory.” Sha’ik argues slaughter achieves victory but L’oric says Leoman long ago pointed out the error of “sequence” in that thinking-that “victory precedes slaughter, not the other way around.” Sha’ik demands to know why neither Leoman nor L’oric brought this up at the discussions and he laughingly points out Dom doesn’t “welcome” discussion. When Sha’ik says Tavore doesn’t either, L’oric labels that irrelevant: “Malazan military doctrine—something Coltaine well understood but . . . Pormqual lost sight of. Tactics are consensual. Dassem Ultor original doctrine . . . ‘Strategy belongs to the commander, but tactics are the first field of battle, and it is fought in the command tent.'” L’oric points out, though, that such a doctrine was predicated on good officers, a core of quality corrupted by the nobleborn infiltration of the officer corps. He goes on to say that Tavore’s personality will have some relevance as tactics come from strategy. He speaks of cold and hot iron, placing Coltaine and Dujek in the cold category but saying Tavore is unknown as of yet. When prompted to explain the idea further, he calls over Mathok to help. Mathok names the following as cold iron: Coltaine, Dujek, Nok, K’azz D’Avore, Inish Garn of the Gral. He continues: “Cold iron, Chosen One. Hard. Sharp. It is held before you and so you reach [and become stuck] . . . the warchief’s soul either rages with the fire of life or is cold with death. Korbolo Dom is hot iron, as am I. As are you . . . we must pray that the forge of Tavore’s heart blazes with vengeance.” Sha’ik says why must Tavore be hot iron and Mathok says, “for then we shall not lose.” Sha’ik is staggered by this and ask what happens if Tavore is cold iron instead. Mathok calls it the “deadliest clash of all,” and L’oric adds “cold iron defeats hot iron more often than not. By a count of three or four to one.” Sha’ik points out that Coltaine lost to Dom though, but Mathok tells her Coltaine and Dom fought nine major battles and Dom won only once, and that was with the help of Reloe and “Mael, as channeled through the jhistal priest, Mallick Rel.” Seeing Sha’ik’s panic, L’oric asks her if she knows Tavore, and if Tavore is cold iron and she nods yes to both. L’oric immediately asks Mathok who among the rebels is cold iron. Mathok replies that Karsa can be both cold and hot, and the only other one is Leoman, who is cold.

SCENE THREE

Corabb Tehnu’alas is introduced, the sixth son of a deposed Pardu chief who had been purchased and saved from a trio of Gral by Leoman. Since then he has sworn his life to Leoman and believes he knows him as well as any. He and Leoman are watching the Fourteenth’s outriders. They plan to attack this night, despite Sha’ik’s orders to the contrary.

SCENE FOUR

L’oric heads for Karsa’s grove, evading probes from the goddess, Febryl, Reloe, Bidithal. He had been surprised to find Sha’ik so “unprepared.” He had expected far worse questioning, especially about where Felisin was, though he wonders if perhaps she had no need to ask, already knowing the answer. An idea that chills him in its implication she may know as well then what Bidithal did to her, and may not care. He senses that the grove is invested, sanctified and hopes it might be a blind spot to the goddess. Though he also thinks Sha’ik is also blinded by her obsession with Tavore, an obsession which grows as Tavore nears; he worries that she is seemingly so afraid of Tavore, whom she clearly knows somehow. He finds Felisin in the grove. She asks him how one can tell Bidithal’s murdering cult from Dom’s and says she’s glad to be able to hid in the glade. She asks if Sha’ik inquired about her and L’oric says no. Felisin responds that “She knows then. And has judged as I have—Bidithal is close to exposing the plotters. They need him, after all, either to join the conspiracy or to stand aside . . . so Mother needs him to play out his role.” L’oric wonders if that is so, and Felisin says that would mean “The Whirlwind Goddess has stolen the love from her soul . . . she [Sha’ik] has been under siege for a long time . . . in any case, she was not my mother in truth . . . a chance occurrence.” L’oric tries to say Sha’ik was returned to the living, but Felisin laughs that off, saying she knows, as she’s sure L’oric, Leoman, and Karsa do, that “Sha’ik Reborn is not the same woman as Sha’ik Elder.” When L’oric says it doesn’t really matter, Felisin disagrees, saying she knew Sha’ik Elder, “knew the truth of her and of her goddess . . . that we are, one and all, nothing but slaves. We are the tools she will use to achieve her desires. Beyond that, our lives mean nothing to the goddess.” She continues that Sha’ik Reborn seemed different, but it seems the “goddess is too strong. Her will too absolute. The poison that is indifference, and I well know that taste L’oric. Ask any orphan and they will tell you the same. We all sucked at the same bitter tit . . . And now . . . every one of us here. We are all orphans . . . Bidithal, who lost his temple, his entire cult. The same for Heboric. Korbolo Dom, who once stood as an equal in rank with great soldiers . . . Febryl [who] murdered his own father and mother. Toblakai, who has lost his own people. And all the rest of us here L’oric—we were children of the Malazan Empire once . . . We cast off the Empress in exchange for an insane goddess who dreams only of destruction, who seeks to feed on a sea of blood.” When L’oric asks if he too is an orphan, she doesn’t bother to answer, “for they both heard the truth in his own pained words. Osric.” Felisin says that leaves only Leoman “unchained.” He tells her he thinks he convinced Sha’ik that Leoman was their last hope. As night falls, L’oric feels an “avid regard” from the two Toblakai carvings and Felisin says they do haunt one. L’oric says it is a mystery that the others are T’lan Imass and Felisin finishes his thought by saying yes, Karsa thought them gods, but Leoman had told her to say nothing to him, adding it would be “a fool indeed to step between Toblakai and his gods.” L’oric says there’s nothing simple about Karsa, to which Felisin replies, “Just as you are not simply a High Mage . .. . You must act soon, you know” and she tells him he needs to make his choices before they are made for him. He says the same could be said about her. They eat.

SCENE FIVE

Sha’ik tries to enter Heboric’s tent and is painfully thrown back by surprisingly powerful wards. She demands he open up and he lets her in: “She stepped forward. There was a moment’s pressure . . . [then] a sudden absence . . . bursting like the clearest light where all had been, but a moment earlier, impenetrable gloom. Bereft, yet free. Gods, free—the light.” She asks what he did and Heboric says the goddess isn’t allowed in his temple. She feels herself returning to herself, “all that I was. Bitter fury grew like a wildfire as memories rose . . . Beneth you bastard. You close your hands around a child, but what you shaped was anything but a woman. A plaything. A slave to you and your twisted, brutal world. I used to watch that knife in your hands . . . that’s what you taught me, isn’t it? Cutting for fun and blood. And oh, how I cut. Baudin. Kulp. Heboric.” Heboric mentions Treach and looking at him, she realizes his tattoos are different and notes his cat-eyes. When he calls her Sha’ik, she tells him not to: “I am Felisin Paran of House Paran . . . Sha’ik waits for me out there, beyond this tent’s confines.” Heboric asks if she wants to go back to the goddess and when she says she has no choice, he can only say “I suppose not.” She suddenly recalls Felisin Younger and how she hasn’t seen her for weeks. She asks where she is, telling him the goddess hasn’t told her when he says the goddess must know. She sees something that scares her in his eyes then and starts to ask what he knows, but he interrupts and pushes her toward the outside, telling her the two of them spoke of Tavore and Febryl and Bidithal and “all is well” then shoves her outside of his wards. She reverts to Sha’ik and thinks just what he’d told her. As she heads back to the palace, Heboric slips out of the tent toward Karsa’s grove.

SCENE SIX

Bidithal sits amongst shadow thinking of Febryl and how “even betrayers can be betrayed.” He believes Febryl and the other conspirators want the warren for themselves, though he doesn’t know why. He knows Sha’ik wants him to find out and he plans to, though he has goals beyond hers, including vengeance on “those foreign pretenders to the Throne of Shadow.” He feels a “they” coming closer, sensing them when he listens very carefully. He thinks “Rashan and Meanas. Meanas and Thyr. Thyr and Rashan. The three children of the Elder Warrens. Galain, Emurlahn, and Thyrllan. Should it be so surprising that they war once more? For do we not ever inherit the spites of our fathers and mothers? . . . But he had not understood the truth of what lay beneath the Whirlwind Warren, the reason why the warren was held in this single place and nowhere else. Had not comprehended how the old battles never died, but simply slept, every bone in the sand restless with memory.” He speaks to his army of shadows, closing his ritual chant, asking if they “remember the dark” then being asked in turn. As they depart, he shivers at “that almost inaudible call . . . They were getting close indeed. And he wondered what they would do when they finally arrived.”

SCENE SEVEN

Dom sits in his tent with his chosen eleven assassins, his whore “plied with enough durhang to ensure oblivion for the next dozen bells.” Five of his assassins used to kill for the Holy Falah’dan prior to the Malazan conquest; three were Malazans he gathered to counter the Claw when he had “a multitude of realizations, of sudden discoveries, of knowledge I had never expected to gain—of things I had believed long dead and gone.” He recalls how there used to be 10 such assassins, proving his need for them. The final three were from the tribes, one of the one whose arrow had killed Sormo E’nath. Dom tells them Reloe has chosen some of them for a “singular task that will trigger all that subsequently follows.” The rest will still have jobs to do, he adds, including guarding him that “fateful” night. He dismisses them then joins an obviously nervous Reloe in an adjoining part of the tent. Dom mocks Reloe’s anxiety, asking who do they have to be afraid of—”Sha’ik? Her goddess devours her acuity—day by day the lass grows less and les aware of what goes on around here. And that goddess barely takes note of us . . . L’oric? . . . . He is all pose and nothing more . . . Ghost Hands? That man’s vanished into his own pit of hen’bara. Leoman? He’s not here and I have plans for his return. Toblakai? I think we’ve seen the last of him . . . Bidithal—Febryl swears he almost has him in our fold . . . he is a slave to his vices, is Bidithal.” Reloe says it isn’t the ones they know he’s worried about; it’s the ones not in the camp, the ones the goddess may let through because she suspects Dom and Reloe of plotting. Dom’s first reaction is to dismiss the idea, then he realizes Reloe may have a point, but then he says the goddess would never risk letting in a Claw—”there’d be no way to predict their targets.” Reloe finally gets across to Dom he’s talking about the Claw making an offer to the goddess (through Topper) to let the Claw in to kill Reloe, Dom, and Febryl, as they’re the ones they form the greatest danger to the Empire’s army, but Dom still thinks it won’t happen, that the goddess won’t listen to any such offer, won’t listen to anyone who “refuses to kneel to her will.” Reloe says okay, but he’ll continue to act under his own beliefs. Dom says fine and dismisses him.

SCENE EIGHT

Korbolo’s whore, Scillara, is actually a plant by Bidithal. She thinks how the durhang helps her not feel pain when Dom mistreats her, and how Bidithal’s rituals help her as well by allowing her to avoid “the weakness of pleasure,” letting her remain indifferent to Dom’s “peculiar preferences” while faking enjoyment of them. She waits for him to sleep, aided by drops she’s put in his wine, then she exits the tent. The guards remark on her frequent visits to the latrines, her throwing up due to the durhang even as they grope her as they “steady” her. She thinks once she might have enjoyed it while being offended, but that is past, and thinks as well that “everything else in this world had to be endured, while she waited for her final reward, the blissful new world beyond death.” As she moves through camp, she recalls her mother as a camp follower of the Ashok Regiment, how her mother sickened and died after the Regiment was shipped overseas. She meets a young girl—one of many orphans sifting through the garbage and waste for salvage—and gives her a message for Bidithal. She also gives her coins, though both she and the girl know that this will anger Bidithal.

SCENE NINE

Heboric arrives in the grove to find Felisin and L’oric, noting “she’s healed well, but not well enough to disguise the truth of what’s happened.” He decides not to show himself, since if the two are hiding there they would try and talk him out of his plan, which is to kill Bidithal. But he begins to worry that his new role as Destriant to Treach will complicate things, cause a convergence or escalation of power if he attacks a priest in his sanctified temple. He decides to wait for a better opportunity, realizing he’ll have to keep his new role secret. He comes across a young girl carrying a bunch of dead rhizan and slips by her unnoticed he thinks. But the girl turns back after he leaves and says, “Funny man, do you remember the dark?”

SCENE TEN

Leoman and two hundred warriors attack the Malazan camp, Leoman employing a sort of primitive Molotov cocktail: clay balls filled with lamp oil and connected by a thin chain and thrown like a bola. As the Malazans regroup, Corabb is about to seemingly be skewered by a dozen crossbolts when his horse goes down, he flies off to dive into a tent wall, and then miraculously ends up somersaulting, landing on his feet, and spinning around just as his horse rolls back for him to jump onto while the Malazan watch him ride off stunned.

SCENE ELEVEN

Leoman and his men gather and he tells them the real point of the attack is about to start as the Malazan’s horse warriors set after them in pursuit, just as he planned.

SCENE TWELVE

Febryl sits watching the dawn. He thinks how “the goddess devoured. Consuming life’s forces, absorbing the ferocious will to survive from her hapless, misguided mortal servants. The effect was gradual . . . it deadened. Unless one was cognizant of that hunger.” He recalls how Sha’ik Reborn has once said she knew all about him, and had been able to speak to his mind, but now he notes she barely does so and he believes he had hardened his defenses so she no longer could, though he wonders if it was just that goddess had turned Sha’ik “indifferent.” He worries perhaps Sha’ik and/or the goddess knows his plans and worries too of Dom’s spies, though he has faith in Reloe since Reloe “had every reason to remain loyal to the broader scheme—the scheme that was betrayal most prodigious—since the path it offered was the only one that ensured Reloe’s survival. And as for the more subtle nuances concerning Febryl himself, well, those were not Kamist Reloe’s business . . . Even if their fruition should prove fatal to everyone but me.” He believes he need not be clever; he just needs to keep things simple. He is startled by Sha’ik’s sudden appearance. When he says he is there to greet the dawn as he does every day, she points out that due to the barrier’s opacity, he’s actually facing the wrong direction. She also says she wants to clarify something: “Few would argue that my goddess is consumed by anger, and so consumes in turn. But what you might see as the loss of many to feed a singular hunger is in truth worthy of an entirely different analogy . . . She does not strictly feed on the energies of her followers so much as proved for them a certain focus. Little different from that Whirlwind Wall out there, which while seeming to diffuse the light of the sun, in fact acts to trap it. Have you ever sought to pass through . . . . It would burn you down to the bone . . . you see how something that appears one way is in truth the very opposite way? Burnt crisp . . . One would need to be a desert-born, or possess powerful sorcery to defy that. Or very deep shadows.” Listening, Febryl thinks he has made the flaw of making “living simply . . . synonymous with seeing simply” and he has realized this too late.

Bill’s Reaction to Chapter Eighteen

I like the little detail that Tavore’s toy soldiers are bone and antler, which I assume means it’s a T’lan Imass army.

We’ve heard the name K’azz D’Avore before—he is a leader of the Crimson Guard. So prepare to hear more of him in the future.

We’ve had a few glimpses that perhaps Tavore might not be a bad leader, but I think this is the first concrete moment of confidence-building—the nine-year-old practicing battle strategies. “Course, the fact she is playing on the side of the “no way to win” can be read as either a good or bad omen. (And don’t ya really want to know if the nine-year-old ever won? Erikson’s not going to give us that one though.)

We’re also shown that “remote” Tavore has been around for some time; it is not merely a matter of her current circumstances.

And does anyone else feel the way this is moving toward tragedy? Here we have a picture of little Felisin so focused on her sister, so taken by her. This is becoming almost Shakespearean in its set-up.

And how about the loaded words in the end of that memory: Tavore as Paran’s “shadow”? Shadow via Shadowthrone and the Shadow realm and its impact on these events. The idea of Paran and Tavore as mirror images—think of how we’ve seen Paran: strong, super independent, what he’s willing to face, and a willingness to tick of the gods. And then, back to the tragic, the “severing”—the two of them separated by events and distance. Will they ever come back together? And what of the third? This is a riven family, a “shattered” one—can it be put back together? The alternative is potentially heartbreaking.

And there’s our archaeologist peeking his head up again in the closing simile of scene one—”the stigma of meaning ever comes later, like a brushing away of dust to reveal shapes in stone.” The buried past, the unburied past: always present in this work.

I always love in these books when characters make these rock-certain pronouncements (and we know what we’ve said about “certainty”) like Sha’ik and how “Even a Hand of the Claw could not pass unnoticed” coming so soon after we see Kalam breach it.

This is an interesting tidbit—the idea that the power of the Whirlwind, the warren, is increasing. What will that mean for the impending clash?

Did I mention Shakespearean? How about that image Felisin conjures up of her—helmed and mysterious and unknown, standing over the beaten and bloody Tavore while scavengers feast on Tavore’s army? Is this the moment of the grand reveal? Or will it be the other way around? Or will Pearl and Lostara succeed before then and tell Tavore what they know, and if so how will that affect the coming clash?

Is it any surprise that Felisin, with all she’s gone through, sees life as a worse punishment than execution? Think of all she is forced to, as she says, “live with.”

Tiny detail—L’oric’s approach is signaled by the crunch of potshards underfoot—we’re always being reminded of how these characters walk on the bones of the past.

Here’s another example of characters being overly trusting in their own insight: Felisin thinking Leoman is no different from her other military commanders (just as we’re about to learn he is in fact quite different—love when their “insights” get punctured so quickly) and that he’s moving in a durhang haze (though that rang a little false to me as she seems to have thought him more than competent when she sent him out).

Here’s another hint that Tavore will have what it takes, in L’oric’s emphasis on strategy—and based on her nine-year-old idea of “fun,” Tavore will have strategy in spades. And we know she’s got some good sergeants (we may be a bit iffy on some higher officers). And then, of course, there is the discussion on cold iron versus hot iron—phrases we’ve seen earlier in the book when Cuttle and Fiddler were talking and Fiddler thought of Tavore: “Iron. Cold Iron. Yes, it’s in her.”

Hard to imagine Tavore “blazing” with anything at this point, isn’t it?

Mallick Rel. Boy I hate Mallick Rel. (But file that Mael guy.)

I do like this scene—the semi-academic discussion of strategy vs. tactics and when one commands and when one allows for discussion; the cold iron and hot iron “gut-level” distinction among commanders; the staggering realization by Sha’ik that her fear may have some ground.

Yea Corabb! Oh, I envy you, Amanda, meeting him for the first time. Yet another of the great Malazan characters.

I mentioned earlier that one of the questions will be will Sha’ik be Felisin or be swallowed by the Goddess? We see young Felisin has noted the same struggle, and sadly has seen that her mother is losing it. And she’s losing to the “poison that is indifference”—that word we’ve seen better and that stands opposed to “compassion.”

And what a bleak roll call of orphans Felisin offers up to L’oric.

“Children of the Malazan Empire” reminds me of a line down the road, but if I told you I’d have to kill you. (Or more likely, you’d want to kill me.)

Only Leoman remains “unchained.” It’s an interesting use of that word coming after a list of orphans, people whom one would think are “unchained” by ties of kinship or collegiality or even nationality. But Leoman—a man who believes seemingly nothing, has faith in seemingly nothing—can truly be said to be unchained. But is that always a good thing?

And here we see poor Sha’ik (Felisin really) as she gets a moment’s reprieve from the battle she’s been waging, waging and losing, clearly. Think of how that absence of pressure must have felt to her—that burst of “clearest light where all had been, but a moment earlier, impenetrable gloom.” The light suddenly shining clear again on what had been done to her—by Beneth, by the Goddess, a suddenly clear image of “all that [she] was.” Once. The recognition that this will be but a moment’s reprieve, that she will be back again. And then to have it end even sooner than she’d thought, so abruptly, with Heboric (and what must that have cost Heboric as well) throwing back into the goddesses “embrace.”

Hmmm, just what is Bidithal hearing coming closer? Despicable, loathsome pervert sadist he may be, but there’s no denying his power here in his temple and with shadow. So good to think he knows what he’s talking about here.

And what is that does lay beneath the Whirlwind Warren? Though are we surprised at all there is something beneath? There is always something beneath in Erikson’s world.

So we’ve got a mysterious master of Talons out there. And now we’ve got a guy surrounded with assassins.

We have another major player introduced in Scillara here, so you’ll want to keep an eye on her Amanda. She’s clearly presented to us early on as someone at an incredibly dark place in her life. A durhang haze. A whore. Yet another orphan. A victim of Bidithal. Worse, perhaps, one who doesn’t see what Bidithal did as making her a victim but freeing her. Someone who waits only to die. We’ll have to see if she stays in this hole or manages, on her own or with help, to somehow climb out. But I’ll give you this—we’ve mentioned the impending symmetry of Heboric’s possible journey back to the jade statue. We’ve got a retracing of step. We’ve obviously got Heboric. We’ve got a Felisin. And a Felisin that has been victimized. And here in Scillara we’ve got a durhang whore victim of abuse. Just saying. (Oh, and we’ll need someone obviously to play the role of Baudin the assassin/talon. Hmmmm.)

Scillara’s father is in the Ashok Regiment. We’ve seen folks of the Ashok Regiment. Have we met her father?

Ahhh, one of the great lies of those who would victimize the innocent and the weak, keeping them in their place: “the harder, the more miserable, the more terrible and disgusting your life, child, the greater the reward beyond death.” Yes, how convenient that “fact” is for those in power.

Speaking of the powerless, and of metaphors made real—how about the orphans weeding through the waste of others for “treasure” to keep themselves alive? Children are dying. And sometimes one wonders if that mightn’t be a mercy.

And here we get a nice characterization of Scillara when she gives the girl the coins, a glimpse that maybe something still exists, an ember that could still be fanned into flame in that soul of hers that is just marking time.

Seems Heboric might need to work on that whole stealth and cunning and “remaining hidden, unseen” thing if he’s going to take on Bidithal, based on his encounter with the young girl.

Leoman. Fire bolas. File.

I love picturing this scene with Corabb. Both the look on his face and then the looks on the Malazans’s face. I so want to see this scene on screen!

Remember that discussion on strategy and tactics? On Leoman as cold iron. Now we’re starting to see what they meant. Not in the attack. But in the way we learn to our surprise (at least my surprise originally) that this was not the “real objective” of the night. This could be a good match-up—this Leoman-Tavore deal.

Plots within plots within plots within plots. I love the, to use the right phrasing, nest of vipers that are conspiring with each other even as they conspire against each other. And isn’t that always the question with regards to a conspiracy of traitors—how can you trust someone willing to betray once not to do so again? Betrayal, it appears, can be habit-forming.

This does not appear like it will end well for Febryl. He’s backed perhaps the wrong horse, something made metaphoric by the way he faces the wrong way these dawns. I love the perspective we get from him at the end. And the delicious understatement of that last line: “Somehow, the newly arriving day had lost its glamor.” Indeed.

You can feel the pace quickening here at this point in the novel. (69% of the way through according to my Kindle.) We’ve got the first true skirmishes as Leoman begins his attacks. We have the realization by Sha’ik that Leoman is their only hope. We’ve got Karsa nearing the end of his journey to find a horse. Heboric moving into a more active acceptance of his new role and skills. L’oric and Felisin recognizing there is little time left to procrastinate—thus getting ready to make their moves—whatever they might be. Conspirators preparing their final moves. And we’ve seen what may be the final stage—the battlefield. The actors aren’t in their places yet, but they’re learning their roles and just starting to put their costumes on. Will this be All’s Well that Ends Well or Hamlet? Or something in between?

Bill Capossere writes short stories and essays, plays ultimate frisbee, teaches as an adjunct English instructor at several local colleges, and writes SF/F reviews for fantasyliterature.com.