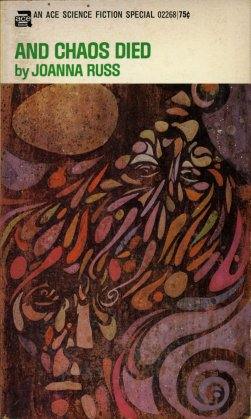

The next book on the reading-stack is the short novel And Chaos Died, published in 1970 as an Ace Special. It was reprinted a few times—my copy is a Berkley paperback—but is no longer in print and hasn’t been since the 1980s. The book was a Nebula nominee and the fourth-place runner up for the Locus Award for Best SF Novel.

And Chaos Died is a strange, psychedelic book that, in many ways, doesn’t age well. (The implicit commentary on male queerness in the text is hair-raising, for one thing—that it’s something to be “cured,” an abnormality not allowed to coincide with greater mental development.) It’s my least favorite of Russ’s works; I wouldn’t likely read it again, beautiful as it is.

Russ begins the book with a translation of a tale by Chuang Tzu, about how the gods Fuss and Fret wanted to thank the god Chaos for treating them well, so they decide to bore orifices into him—as he had none, and was featureless—which kills him. The title comes from the last line of this morbid little myth. It makes for a rather dire opening thematic statement, one to keep well in mind as the novel unfolds.

And Chaos Died is definitively New Wave SF, concerned as it is with psychic phenomena, mind-bending imagery, nearly impenetrable—but beautiful—prose and an experimental sensibility. It’s not an “easy” book; in fact, after the straight-forwardness of The Adventures of Alyx, it feels in some ways like a book written by a completely different person. They’re difficult to read back to back, but the juxtaposition shows the sheer range of Russ’s writing abilities: she’s as comfortable with the experimental as she is with the adventure-story; her prose can shift and evolve to handle whatever material she needs to handle.

However, despite the level of craft-skill on display in And Chaos Died, my feelings for the book are mixed—as I’ve said, it’s my least favorite of Russ’s novels. I find its sexual politics deeply problematic. Also, on a more workmanlike level, scenes in the text are at times exaggerated to the point of silliness, as if the project of developing such an experimental narrative got away from Russ and started gallivanting around on its own. As I read, I noted that it often felt like I was scrabbling at a rock face, trying to find a grip into the story and failing—the emotional connections weren’t there; the characters sometimes felt like dolls being moved about a stage. The push to validate the thematic statement of the text devours the potential for meaning and connection; it becomes an extended allegory, in its way.

I find it deeply interesting to see Russ not quite getting it right—again, because my entry-points to her work were her most acclaimed pieces, where everything was just about perfect. And Chaos Died is something else. It has rough edges.

That doesn’t mean the book isn’t startling and intense, because it is. The blurb on the back of my Berkley paperback by Samuel Delany says, “Many novels have dealt speculatively with psi-phenomena, describing the effects on people and society. Ms. Russ has taken it on herself to put the reader through the experience.” (May I note how jarring and weird it is to see her name written as “Ms. Russ?”) I’d say he’s got the right of it. The most intense, vibrant, weird parts of the book are her descriptive flights during the scenes of psychic phenomena—the imagery is like a blow to the gut; it’ll steal your breath and send starbursts of sensation and wonder through your brain. Her lines are referential on a grand scale, containing allusions by the fistful, often several per sentence—there are layers and layers of echoes and meanings in Russ’s prose. It’s impossible to exaggerate how dense and beautifully crafted And Chaos Died is.

For that alone I’m glad that I read this novel, though in the end it didn’t win me over.

I suspect the thing that puts the book firmly in my “not again” pile, more than the puppet-like characters, is the sexual politics. Jai Vedh, the only male protagonist in Russ’s entire oeuvre, is introduced as a “homosexual.” At first, it seems that Russ is going to explore homophobia and prejudice against male queerness—the military officer who Jai crash-lands with is a big-macho masculine guy, who’s constantly responding badly and violently to Jai. There’s a lot of tension; Jai derisively tells him at one point, “I won’t touch you. Not even in your sleep. Calm down…” The captain’s response is to get even antsier and eventually try to physically throw him out of the small escape-pod spacecraft. So far, so good, I suppose; the explorations of masculinity and homophobia are interesting.

It starts to get bad when the psychic society comes in, because Jai ends up getting together with a woman who uses her powers to “cure” him of his sexuality, which is framed as a dysfunction. They become lovers, and he’s all fixed from being gay, because when his mind begins to expand and he develops abilities like hers, he becomes heterosexual. It turns out, being gay was just a problem caused by his society, and when he’s mentally healed he’s straight. In this construction, straight equals healthy, straight equals better, straight equals right. It’s exactly the party line of the psychiatric associations of the 60s and 70s: gay is sick, straight is healthy.

What?

I had a fairly visceral “you have got to be fucking kidding me” reaction to that scene. I nearly threw the book. It’s hard to believe that Russ, about to publically become an advocate for queer women’s sexuality in her next novel, could make such a nasty implication—that all a gay man needs is a good woman to make him straight. How many times do lesbians have to listen to the reverse, that a good man is all they need to give up other women? Hell, deconstructing that myth is part of the point of The Female Man.

Is it because Jai is male? Does his gender really make such a categorical difference in the validity of his identity and sexuality? There are threads of this tendency in second-wave feminism, so it’s not like it’s new; I likely shouldn’t be surprised, but I was. It felt like a betrayal.

That’s in addition to the fact that nearly every sex scene or sexual scene has elements of non-consent, on the parts of both men and women; Jai isn’t really willing to have sex with the woman the first time, but she makes it happen. Perhaps this is supposed to feed into the point that Jai’s society is so absolutely wrecked, socially, that aggression and violence are the only possibilities for interpersonal relation. If it is, it only succeeded in making me extremely uncomfortable and a bit disgusted—the sex scenes don’t seem to be written to be icky on purpose, and there aren’t many hints in the text that there’s anything wrong with the dubious consent. It’s just—there. It’s how sex is in And Chaos Died. I can read books with sexual violence, when there’s a point, but I didn’t get that vibe here.

And Chaos Died has its bright points, make no mistake, and it’s valuable as a part of Russ’s bibliography. It was popular with its audiences when it came out, as evidenced by the awards nominations. However, I finished it upset and disgruntled, tangled between the beautiful parts and the ugly parts, unsure of how I should feel. I’m a fan of Russ as a whole, but not this book. This book says things that I cannot agree with, that I in fact find reprehensible.

I’ve already discussed The Female Man as part of the Queering SFF series, so I’ll direct you to that here. The next book to discuss after that is We Who Are About To…, a wrenching, deconstructive novel about a crashed spaceship.

Lee Mandelo is a multi-fandom geek with a special love for comics and queer literature. She can be found on Twitter and Livejournal.