This is the second in a series of posts by Sarah Monette on Ellery Queen. You can read the first one here.

When I was in college (at Case Western Reserve University) I had two outstandingly awesome professors. One of them is the reason I became a Shakespearean; the other very nearly made me into a Victorianist instead. It’s the Victorianist who’s influencing this essay, because of a trick she used in teaching Wuthering Heights.

We had the Norton Critical Edition of Wuthering Heights (3rd edition), with its freight of supplementary material, and what she did was to start one class by talking about the apparatus surrounding the text and how, in the particular case of Wuthering Heights, that apparatus—Preface to the Third Norton Edition, Preface to the First Norton Edition, and then, after the text of the novel itself, the textual commentary from the editor, Charlotte Brontë’s biographical note from the 1850 editon of Wuthering Heights, some examples of contemporary reception, and some examples of modern literary criticism—was a series of framing devices, just as the novel itself is made up of a series of framing devices. (We looked particularly at the efforts Charlotte Brontë made to reblock her sister Emily into a more socially acceptable form.) That class session did more than anything else to make me aware of books separate from the stories they contain—and aware that the packaging surrounding a story may be just as much an effort at storytelling as the story itself.

Now, you may legitimately ask, what on earth does this have to do with Ellery Queen?

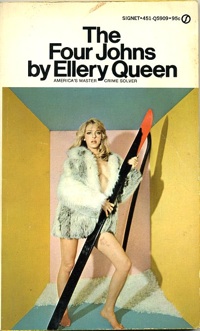

Two things, one tangential and one that actually leads to my point. The tangential matter is the amusement value of watching publishers of later decades trying to repackage Ellery Queen to be more “appealing.” Signet in the late 60s and early 70s is the most notable culprit here, with its ludicrous soft-porn covers—as for example on The Door Between, The Four Johns, The Four of Hearts—and the scramble in the jacket copy to make the story itself sound like something completely different. My favorite example is The Egyptian Cross Mystery:

Swingers in the sun—and murder in the shadows . . .

The island was a magnet for every seeker of kinky kicks and far-out thrills. A weird bearded prophet and his splendidly handsom assistant had made it the home of a new religion—one that worshiped the sun, called clothing a crime, and recognized no vice save that of inhibition.

It was a shame and a scandal, said the old time residents. But soon it was more than that. Kooks were one thing, but corpses were another—and Ellery Queen arrived in nudist land to find that everything was in easy view except one fiendish killer. . . .

Now, it is true that The Egyptian Cross Mystery features a nudist colony/sun cult on an island, but there’s no suggestion of any sexuality more deviant than adultery of the most plebeian and old-fashioned sort, and the novel itself is not set on the island or among the nudists—and in fact has nothing whatsoever to do with anything described in the blurb. (The sun cult is a badly integrated red herring, and I’ll have more to say about it at a later date, as The Egyptian Cross Affair is an interesting case study in how not to make your red herrings work.) These books, therefore, are a particularly obvious—one might even say blatant—example of how packaging can tell a story. Or can try to, anyway.

This idea is particularly apropos to Ellery Queen, because the beginning of their career is marked by an obsessive attention to exactly that: packaging the detective story. Dannay and Lee also did a lot of extra-textual work in that direction, including making author appearances masked, but I want to focus on the text, because it’s the text that a reader today engages with.

Ellery Queen novels tend, from beginning to end of their career, to be apparatus-heavy. Dramatis personae (frequently rather flippant—although the tone changes over the years from supercilious to gently self-mocking), maps,* the famous Challenge to the Reader, and the forewords (in the early books) by “J. J. McC.,” a stockbroker friend of Ellery’s who claims responsibility for the stories seeing print at all.

*On another tangent, why are fantasy and Golden Age detective fiction the only two genres that have love affairs with maps?

The effect of most of this apparatus is to highlight the fictionality of the story. We are being asked at every turn to remember that this is make-believe, a game being played between author and reader. This idea is, of course, a hallmark of the Golden Age, and Ellery Queen was not the first to articulate or espouse it. He/they is simply the first one to make it explicit in the text, with the device of the Challenge. If you’re not familiar with early EQ, the Challenge to the Reader is a formal interjection, generally about three-fourths to four-fifths of the way through the novel, in which the reader is directly informed that s/he has all the information necessary to solve the crime. (In The Roman Hat Mystery, this interjection is made by J. J. McC.; mercifully, it was handed over to Ellery by the time they wrote the next book, The French Powder Mystery.) The Challenge is always explicitly about the mystery as a detective novel, and talks about “the current vogue in detective literature” (TRHM 202) and Ellery’s own experiences as a reader of detective fiction (TFPM 220) rather than as a participant/detective.

Because of the dual nature of “Ellery Queen” (discussed in my first post here, the Challenge can be read one of two ways:

1. Ellery Queen the character breaking the fourth wall to talk to the reader.

2. Ellery Queen the author interrupting the dream that John Gardner said should be vivid and continuous to remind the reader, not merely that this is fiction, but that it is a particular kind of fiction: that it is a puzzle, a game. “You’re all a pack of cards,” as Alice says.

Early Ellery Queen books show a pronounced tension between options 1 & 2 above. In a sense, they (Dannay and Lee) are trying to do both. They’re maintaining the fiction that Ellery Queen is a single, real individual (since even in option 2, it’s still Ellery Queen the construct speaking to the reader) at the same time that they’re emphasizing the artificiality of the books in which he appears. Part 2 of “Packaging the Detective” will look at how this tension plays out in the front matter of The Roman Hat Mystery.

Sarah Monette wanted to be a writer when she grew up, and now she is.