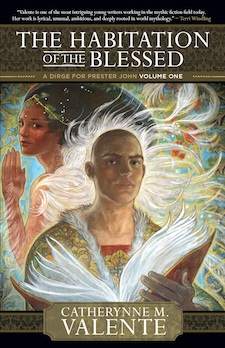

We hope you enjoy this excerpt of the first three chapters from Catherynne M. Valente’s latest book and the first in the A Dirge For Prester John series, The Habitation of the Blessed, out now from Night Shade Books.

John, priest by the almighty power of God and the might of our Lord Jesus Christ, king of kings and Lord of Lords, to his friend Emanuel, Prince of Constantinople: Greetings, wishing him health, prosperity, and the continuance of divine favor.

Our Majesty has been informed that you hold our Excellency in love and that the report of our greatness has reached you. Moreover, we have heard through our treasurer that you have been pleased to send to us some objects of art and interest that our Exaltedness might be gratified thereby. I have received it in good part, and we have ordered our treasurer to send you some of our articles in return…

Should you desire to learn the greatness and Excellency of our Exaltedness and of the land subject to our scepter, then hear and believe: I, Presbyter Johannes, the Lord of Lords, surpass all under heaven in virtue, in riches, and in power; seventy-two kings pay us tribute… In the three Indies our Magnificence rules, and our land extends beyond India, where rests the body of the holy apostle Thomas. It reaches towards the sunrise over the wastes, and it trends toward deserted Babylon near the Tower of Babel. Seventy-two provinces, of which only a few are Christian, serve us. Each has its own king, but all are tributary to us.

—The Letter of Prester John,

Delivered to Emperor Emanuel Comnenus

Constantinople, 1165

Author Unknown

We who were Westerners find ourselves transformed into Orientals. The man who had been an Italian or a Frenchman, transplanted here, has become a Galilean or a Palestinian. A man from Rheims or Chartres has turned into a citizen of Tyre or Antioch. We have already forgotten our native lands. To most of us they have become territories unknown.

—The Chronicle of Fulcher of Chartres

Jerusalem, 1106

THE FIRST MOVEABLE SPHERE

There is also in our territory a sandy sea without water. For the sand moves and swells into waves like the sea and is never still. It is not possible to navigate this sea or cross it by any means, and what sort of country lies beyond is unknown… three days’ journey from this sea there are mountains from which descends a waterless river of stones, which flows through our country to the sandy sea. Three days in the week it flows and casts up stones both great and small, and carries with it also wood to the sandy sea. When the river reaches the sea the stones and wood disappear and are not seen again. While the sea is in motion it is impossible to cross it. On the other four days it can be crossed.

Between the sandy sea and the mountains we have mentioned a desert…

—The Letter of Prester John, 1165

THE CONFESSIONS OF HIOB VON LUZERN, 1699

I am a very bad historian. But I am a very good miserable old man. I sit at the end of the world, close enough to see my shriveled old legs hang over the bony ridge of it. I came so far for gold and light and a story the size of the sky. But I have managed to gather for myself only a basket of ash and a kind of empty sorrow, that the world is not how I wished it to be. The death of faith is tasteless, like dust. Such dust I have unearthed by Your direction, Lord, such emerald dust and ruby sand that I fear one day I shall wake and my vision will be clouded in green and scarlet, and I shall never more see the world but through that veil of jewels. I say I have unearthed this tale—I mean I have taken it from the earth; I have made it no longer of the earth. I have made the tale an indentured slave, prostrate beneath air and rain and heaven, and tasked it to burrow under the great mountains and back to the table at which I supped as a boy, to sit instead among barrels of beer and wheels of cheese, and stare at the monks who raised me with such eyes as have pierced me these many weeks. They sent me here, which is to say You sent me here, my God, and I do not yet have it in me to forgive either of you.

But I plead forgiveness for myself. I am a hypocrite—but You knew that. I desire clemency for the tale I send back over the desert. It is not the tale I wished to tell—but that is not the fault of the tale. If a peasant loathes his son for failing to become king, blame must cleave to him, and not to his poor child. Absolve this tale, Lord. Make it pure and good again. Do not let it suffer because your Hiob is a poor storyteller, and struck that peasant child for lack of a crown. The tale is not weak, yet I am. But in Truth is the Light of Our Lord, though the beacons and blazes of centuries gone have grown diffident and pale of late, still I have never lied. I could sell my soul to the demons of historiography and change this tale to suit my dreams. I could do it and no one would think less of me. It has been done before, after all. But before my Lord I lay the pain and anguish of the truth, and ask only to be done with it all.

Our troupe arrived in the provinces of Lavapuri in the Year of Our Lord 1699, in search of the Source of the Indus River. Officially, we had been charged to shine a light in a dark place, to fold up the Dove of Christ into our saddlebags and bear Him unto the poor roughened souls of the Orient. Of course You know better, Lord. You saw us back home, huddled together and dreaming of gryphons and basilisks. And in the crush of our present heat and dry wind I well recalled those frigid, thrilling nights at home, crouched in the refectory, when a man was compelled to break the ice on his milk before he could drink. In the cold lamplight we whispered brother to brother. We hoped to find so much in the East, hoped to find a palace of amethyst, a fountain of unblemished water, a gate of ivory. Brushing the frost from our bread, we dreamed, as all monks had since the wonderful Letter appeared, of a king in the East called Prester John, who bore a golden cross on his breast. We whispered and gossiped about him like old women. We told each other that he was as strong as a hundred men, that he drank from the Fountain of Youth, that his scepter held as jewels the petrified eyes of St. Thomas.

Bring word of him, the Novices said to me. Tell us how the voice of Prester John sounds in your ears.

Bring gifts to him, my Brothers said to me. Tell us how the hand of Prester John weighs on your shoulder.

Bring oaths to us, the Abbot said to me. Tell me how he will deliver us from the Unfaithful. Also in your travels, if the chance presents itself without too much trial, endeavor to spread the Name of Christ into such lands as you may.

Yes, they did tell me to convert and enlighten the savages. But my Brothers’ mouths were so full of golden crosses and the names of kings. I could hardly hear them.

The Indus seeped green as a weeping eye, and our horses’ delicate ankles did not love it well. The dust of the mountains was red beneath grey, and to me it seemed as if the stones bled. The younger Brothers quarreled among themselves as to who should have the delight of hunting the shaggy, truculent sheep of these parts, and who should have the trial of staying with old Hiob in case he needed a less wizened mind to recall scripture and blessings, should we ever meet a soul in need of scouring in these crags of the dead. Two of our number had died already: Brother Uriel fell from a stone jut to his death, and Brother Gundolfus perished of an insect bite which grew to the size of an apple before he showed it to us. I am ashamed to say I was overcome by thirst, and Brother Alaric was compelled to administer their Rites. We buried them both beside the pilgrim road.

But I do not wish to furnish You with a litany of the sufferings of my small band—You know where we failed, where we starved. You know how many had gone to Your same cruel river. Truly, only You know the exact number of fools who came strident and arrogant, making the same demands of the locals: that they must lead them to the cathedral-palace of Prester John on the double, and do not forget to point out the Fountain of Youth along the way! You know how the mountain-folk laughed at them, or called them mad, or flayed them and gave those pilgrims over to the Indus to decide their fates. Uriel and Gundolfus were good men, and at least they died still hoping to see the Priest-king one day; their goodness has been faithfully recorded, and Christ alone knows their sins.

The sky bolstered a spiteful sun, whose dull, thirsty light was scarcely enough to lift our eyes to heaven. Yet the river was true, and cold, and we drank often. Sharp, spicy leaves were all we found to eat for many days—all the squabbling over who was the greater hunter meant little when the sheep were cleverer than the monks. It was not until the thirteenth day—unlucky, yes, but Hiob cannot be blamed for happenstance!—since we had entered the coriander-strewn provinces of Lavapuri that we came upon a village, and a woman, and a word.

The village was mean: twelve small huts and a larger house, some local fiefdom. The village, too, glowered grey and dull in our sight, as though it had burned once, so fast that the ash remained in the shapes of daub and stick huts, in the shape of scraggle-haired goats, in the shape of sharp-ribbed children. The sun lies too close to the earth in this place.

The woman was tall, her clay-colored skin dark and sunburned beneath smudges of charcoal and dust. She wore a yellow robe, wet at the hem where she had been in the river, pulling reeds into her basket to wrap the evening’s rooster, which she carried by the broken neck in one slim hand. And so she seemed to me a candle in the grey mere, a benevolent Virgin in gold, her arms all full of green. Her eyes unsettled me, being a shade of dusty gold like an illuminated page, and tired, greatly grieved. Thin, white hair prickled on her arms and shoulders, not unpleasant to look at, though I am not accustomed to marking a woman’s bodily hair, and felt a dim flame in my cheeks even then, noticing how her silky down fairly glowed against her dark skin. I went to her, with three of my novices clutching crosses to their young and rampant breasts. I stumbled in my eagerness—I beg forgiveness for that indignity.

“Lady,” I said to her in the liquid syllables of her own Mughal dialect, for in Your kindness You graced me with a love for foreign tongues, and an ease in their learning. “Tell me!” I said to her, as every fool priest must have done to every poor unbaptized goat-wife since this whole business began. “Where is the great king Prester John?”

She blinked at me, no doubt surprised to hear her own ululating dialect spill from the mouth of a foreigner, and then bent her head as if in prayer, as if in acknowledgment of some old sorrow long past its sting, and her scalp gleamed dully in the slant-light. When she raised her head, she looked down the long scrub-specked plain from whence she had come and sighed through her nose, her lips clamped tight against speech, her reeds already wilting.

Then she spoke her word. Everything that followed was born in that moment, from her mouth, in the dusk and the dust and all of us waiting on her like suitors on a princess.

The word was: Gone.

How can such a man be gone? The Letter tells us he has clapped up the Cup of Life within his treasure-house, that the Fountain of Youth bubbles in his courtyard like a pretty Italian marble. Surely his heart swells still; five hundred years is but a cough in the long breath of such a potentate. We were not the first to come with a vision of him blazing like the Sacred Heart in our bones—but none yet had reported him dead, or even reduced in splendor. Yet the woman in yellow shook her head and would not say his name or her own. She took us instead up the small path to the low-roofed house of her Lord, who was called Abbas and presided grandly over a field of rice, fourteen sheep, and a healthy family of breeding goats. The villagers lounged in his hall, laughingly gulped his fermented milk, lustily ate his rice, kicked his one-eared dog and called him the son of a second wife while he smiled ruefully at me, as if to say: What may a Lord do on this earth but love the roughest of men and care for them as children?

Our yellow-eyed guide knelt at a fire set into the floor of the Lord’s house, and put her reed-wrapped rooster under the embers. Its scent broke the air into savory sighs, and Abbas kissed her brow as though she were a favored sister, or a daughter whose mother had gone before her. He cupped her face in his brown hand, and it was he who fed her when the chicken had done! She knelt before him, though I did not see in her the submissive aspect of a demure and humble woman. It seemed only that she felt it most comfortable to kneel while Abbas placed each golden slice of roasted flesh carefully on her tongue with his own fingers, as if she were the queen and he a slave bound to her ankle. The hall was quiet during this strange rite; the shabby courtiers did not speak nor drink nor torment hounds, and in the corner of the hall, a man wept softly.

By the time she had finished her meal, the sky had cooled, a flush of pink rising in the east, as if the deeds of men embarrassed the heavens. Slowly, conversation took hold of the room once more. A pleasant sort of flute and drum struck up, played by two children, twins most likely, with our guide’s same downy white hair on their bony shoulders. The tune felt sad against my ears, and against those of Brother Alaric and the others as well, if my guess is correct. When the men had returned to gossiping about whose daughter had snuck about with whose son, the woman in yellow left her Lord and took up my hand in hers. The eyes of Abbas followed us as we withdrew from the hall, and those of all the village, too.

She would take only myself: the novices Abbas bade to stay, plying them with goat-liver and chickpea-mash—for once I was not sorry to miss a meal. Young men are often satiated by a little rich food and strong drink, but at my age my liver cannot bear very much of anyone else’s. In the red shadows of those toothed mountains my silent Virgil took me through that long plain of garlic-flowers and withered plants, a field agued and sallow. Beneath my feet, O Lord, Your earth sagged in its dying. There are places older than Avignon, older than Rome, and the world there is so tired it cannot rouse itself, even for the sake of guests.

We reached the edge of the plain, where it shed all growing things and began a sheer rise into blue stone and thirst. There she knelt as Eve beside a tree, and beside that tree I laid too all my faith and learning, all that which is Hiob and not another man, and nevermore from that spot would my soul move.

This tree bore neither apples nor plums, but books where fruit should sprout. The bark of its great trunk shone the color of parchment, its leaves a glossy, vibrant red, as if it had drunk up all the colors of the long plain through its roots. In clusters and alone books of all shapes hung among the pointed leaves, their covers obscenely bright and shining, swollen as peaches, gold and green and cerulean, their pages thick as though with juice, their silver ribbonmarks fluttering in the spiced wind.

I leapt like a boy to catch them up in my hands—the boughs arched thick and high, higher than any chestnut in our cloister orchards, knottier than the hoary pines which cling to the sea-stone with roots like arms. In Eden no such tree would have dared to grow so high and embarrass the Lord on his Chair. But in that place I felt with a shudder and chill that You had turned Your Eye away, and many breeds of strangeness might be permitted in Its absence.

I managed to snatch but one sweet fruit between my fingertips—a little brown hymnal that had been a fair feast for worms and parrots. I opened its sleek pages—a waft of perfume assailed my senses. Oh! They smelled like crisp apples soaked in brandy! The worms had had the best of the thing, but there on the frontispiece, I saw a lovely script, elegant and sure, and in a language I could read only with difficulty, a tongue half-infidel and half-angelic, I read:

Physikai Akroaskeos, or,

The Book of Things Made and Things

Born

Authored by the Anti-Aristotle of

Chandrakant on the Occasion of his

Wife’s Death

in the Seventeenth Year of Queen Abir

Translated and Transcribed by Hagia of

the Blemmyae during several Very

Pleasant Afternoons during

the Lenten Fast, commonly Called the

Weeks of Eating in Secret, in New

Byzantium, Under an Ink-Nut Tree.

Only two pages remained intact, the others ruined, a rich feast for some craven bird—and in my heart I cursed the far raven in whose belly my lost pages whispered to its black gizzard. You see? I already thought of them as mine. I touched the lonely, clinging page with a finger, and it seemed to brown like the flesh of a pear beneath my skin:

As an indication of this, take the well-known Antinoë’s Experiment: if you plant a bed and the rotting wood and the worm-bitten sheets in the deep earth, it will certainly and with the hesitation of no more than a season, which is to say no more than an ear of corn or a stalk of barley, send up shoots. A bed-tree will come up out of the fertile land, its fruit four-postered, and its leaves will unfurl as green pillows, and its stalk will be a deep cushion on which any hermit might rest. Every child knows this. It is art that changes, that evolves, and nature that is stationary.

However, since this experiment may be repeated with bamboo or gryphon or meta-collinarum or trilobite, perhaps it is fairer to say that animals and their parts, plants and simple bodies are artifice, brother to the bed and the coat, and that nature is constituted only in the substance in which these things may be buried—that is to say, soil and water, and no more.

A fat orange worm squirmed out of the o in Antinoë, and I flung the hymnal away in disgust. Immediately I flushed with shame and crawled for it, clutched it back, worm and all. A book is worth a worm or two, even vermin so fat and gorged as the one which even then oozed around the spine unconcernedly. I should have honored all Thy creatures, my Lord, and bowed to the worm, who after all, came first to this feast. I seized the last page, which tore free in my hand with a sound like a child’s cry. It read:

That which is beloved is the whole of creation.

Yet there must be an essential affinity, a thing which might be called the blood of the spheres, which exists between and among that which we have determined is artifice and that which we have determined is natural, e.g. Pentexore and all it contains and the soil and water which produce Pentexore and what folk call “creation.” For if it is created, it cannot be natural!

In my heart I see all things connected by diamond threads, and those threads I call the stuff of affinity. But I am an old man, and my son makes the palm-wine far too strong these days, and the sun burns my pate.

It is with these thoughts in my heart that I go to bury you, my sweet Pythias, in the black field where you planted sugar cane last spring, beside your orange bride’s veil, whose gauzy flowers still blow in the salt-wind off of the Rimal. It is with these thoughts that I will water the bed of veils and cane all winter long, and hope to see your face swell like fruit from some future hanging bough.

“Is there no more?” I cried.

The woman in yellow shrugged her downy shoulders. Finally, she spoke, a full sentence, falling reluctantly from her mouth like a costly jewel.

“Birds and beasts must feast as men do. I do not deny them their sustenance.”

In a madness I turned from her, and in a madness I clambered up into the scarlet tree as no man my age should do, reaching for the book-fruit, stretching out my veiny fingers to them. They glittered and swung away from my grip in the hot breezes, the green and the gold fluttering, the covers stamped with serpents, with crosses, with curved swords, with a girl whose right arm was a long wing.

Below me, my guide made a sign with her long fingers. Three, her hand said. Three alone.

Of course, it must forever and always be three. Three is Thy number, O Lord, of Thy Son and Thy Spirit. How wicked of me, no better than a worm or a raven, to strip the tree for my own gorging. I breathed to calm my heart and reached out again, to the brambled deeps of the tree. I sought out the most complete volumes, in the nests of branches where no hoopoe crept, and this time my grip fell firmly on them, cool and firm as apples.

I drew forth first: a golden book bearing a three-barred cross on its cover. Second: a green antiphonal with a wax seal over its pages that showed a strange, elongated ear. Lastly I strained to pluck, furthest from my reach, a book as scarlet as the leaves of the great tree. A pair of staring eyes embossed on its cover seemed to rifle my soul for riches, finding less than they hoped for. Cradled in the fork of the tree, I opened the pages of my last ripe fruit, my prize, and on the page was the same certain hand as had recorded the strange science of Anti-Aristotle. But it was not the same book—the paper shone a pale, fresh green, and small paintings grinned and gamboled at the edges. Perhaps the same scribe had copied both—to be sure many books in our Library bear my own hand.

I bent my face close to the script, squinting—and onto that page my heart fell out, for the sweet-smelling book promised no hope.

We carried the body of my husband down to the river, he who was once called king, called Father, called, in the most distant of days, Prester John.

The river churned: basalt, granite, marble, quartz—sandstone, limestone, soapstone. Alabaster against obsidian, flint against agate. Eddies of jasper slipped by, swirls of schist, carbuncle and chrysolite, slate, beryl, and a sound like shoulders breaking.

Fortunatus the Gryphon carried the body which had been called John on his broad and fur-fringed back—how his wings were upraised like banners, gold and red and bright! Behind his snapping tail followed the wailing lamia twelve by twelve, molting their iridescent skins in grief.

Behind them came shrieking hyena and crocodiles with their great black eyes streaming tears of milk and blood.

Even still behind these came lowing tigers, their colors banked, and in their ranks sciopods wrapped in high black stockings, carrying birch-bark cages filled with green-thoraxed crickets singing out their dirges.

The panotii came behind them, their great and silken ears drawn over their bodies like mourning veils.

The astomii followed, their mouthless faces wretched, their great noses sniffing at the tear-stitched air. At their heels walked the amyctryae, their mouths pulled up over their heads as if to hide from grief.

The red and the white lions dragged their manes in the dust; centaurs buried their faces in blue-veined hands.

The meta-collinara passed, their feet clung with hill-dust, clutching their women’s breasts while their swan-heads bobbed in time to some unheard dirge of their own.

The peacocks closed the blue-green eyes of their tails.

The tensevetes came, ice glittering in their elbows, the corners of their eyelids, the webbing of their fingers, the points of their terrible teeth. And from all these places they melted, woeful water dripping into the dusty day.

The soft-nosed mules threw up their heads in broken-throated braying.

The panthers stumbled to their black and muscled knees, licking the soil from their tears.

The blue cranes shrieked and snapped their sail-like wings sorrow-ward.

On spotted camels rode the cyclops, holding out into the night lanterns which hung like rolling, bloodshot eyes, and farther in the procession came white bears, elephants, satyrs playing mourn-slashed pipes, pygmies beating ape-skin drums, giants whose staves drew great furrows in the road, and the dervish-spinning cannibal choir, their pale teeth gleaming.

Behind these flew low the four flame-winged phoenix, last of their race.

Emeralds rolled behind like great wheels, grinding out their threnodies against the banks.

And after all of these, feet bare on the sand, skirts banded thick and blue about her waist, eyes cast downward, bearing her widow’s candle in both hands, walked Hagia of the Blemmyae, who tells this tale.

I sat in the house of Abbas, my habit and hood full of fruit. The book-plums left a sticky honey on my hands, and they tasted, oh, I can remember it still—of milk and fig and a basket of African coconuts Brother Gregor once brought home to the refectory from sojourns south. I stared at my precious three books with the eyes of a starving child—could I not somehow devour them all at once and know their contents entire? Unfair books. You require so much time! Such a meal of the mind is a long, arduous feast indeed. And then I was seized with terror: What if they rotted as fruit will do? What if time and air could steal from me words, passages, whole chapters? I could not choose; I could not bear to choose, and the liver-scented snoring of my novices rose up to the rafters.

I decided to make a liturgy of my reading. I would fashion my work in the image of Thy Holy Church. I would read and copy for an hour from each book, so that they would all rot—and I too, in my slower way—at the same pace, and no book should feel slighted by preference for another. All those fleshy, apple-sweet riches I meant to bear home intact to my Brothers in the cold of Luzerne.

I could choose no other than the book with the golden cross on its cover to begin: I am ever and always the man that I am, a man of God and the Cross, and that cannot be altered. I believe now that You put these books in my path, O Lord, with Your mark upon them so that I should know that You moved on the face of my fate as once on the deep waters of the unmade world.

I reached for salvation, and opened its boards like curtains.

THE WORD IN THE QUINCE

an Account of My Coming to the Brink

of the World, and What I Found There.

As told by John of Constantinople

Committed to Eternity by his Wife,

Hagia, who was afterward called

Theotokos

Chapter the First, in which a Man is

delivered into India Ultima by means of

a Most Unusual Sea, and thereby forgets

the names of the Churches of

Constantinople.

Salt and sand sprayed against the hull, which the roasting wind had peeled of scarlet paint and bared of gilt. The horizon was a golden margin, the sea a spectral page. Caps of dusty foam tipped the waves of depthless sand, swelling and sinking, little siroccos opening their dry and desultory mouths. Whirlpools of dead branches snapped and lashed the bulging sides of the listing qarib; sand scoured her planks, grinding off crenellations and erasing the faces of a row of bronze lions meant to spray fire into the sails of enemies. The name of the ship was once Christotokos, but the all-effacing golden waves had scraped it to Tokos, and thus new-baptized, the little ship crested and fell with the whim of the inland sea.

I huddled against the wretched mast. A few days previously, a night-storm had visited this poor vessel, and its boiling clouds littered the deck of the ship with small dun mice. They tasted the mast, found it good, and stripped it to a spindly stick. In the morning, they leapt overboard as one creature, and I, lone inhabitant of the wretched Tokos, watched as they bounded away on the surface of the sand, buffeted by little licking waves, unconcerned, their bellies full of mast. I captained this thin remnant of naval prowess as best I could: shuddering, blister-lipped, no sailor, no oarsman, not even a particularly strong swimmer. My teeth hurt in my jaw, and my hands would not stop shaking—the true captain had leapt overboard in despair—a month past, now? Two?—and the navigator followed, then the cook, and finally the oarsmen. One by one as the sand snapped off their instruments they leapt overboard into the dust like mast-fed mice. But the sea did not bear them up, and they drowned screaming. They each watched the others sink into the glitter and grime, but believed in their final wild moments that theirs would be that lucky leap that found solid land. That they would be blessed above the others. Each by each, I watched the sand fill up their surprised and gaping mouths.

I ate the sail one night and dreamed of honey. The stars overhead hissed at me like cats.

Every morning, I prayed against the wheel of the ship, knees aching against the boards, the Ave Maria knotted like a gag in my mouth, peeling my lips open against those blasting hot winds that always smelled of red rock and bone-meal. But Mary did not come for me, no blue-veiled mother balancing on the shattered oars, torso roped with light. Still, I counted the beads of an invisible rosary, my body wind-dry of tears. The dawns were identical and crystalline, and the sand kept its own counsel, carrying the ship where it willed, with no oar or sail to defy its will.

Some days, I seemed to recall that my name was John. Searching my memory, I found Constantinople lying open as a psalter, the glittering quays blue and green and full of splashing mackerels, the trees dripping with green peacocks and pomegranates—and the walls so high! And I, I thought, I myself sat upon those walls. I remembered the city’s name, but not my own. A scribe with kind eyes sat at my side, and drank quince-wine with me as the sun spent itself gaudily over golden domes behind us. Mosaics glowed in my heart, dim as a dream, removed pebble by pebble and replaced and removed again as the whims of Patriarchs and Empresses decreed—until like my ship no gilt remained, and seabirds began to make off with the cobalt-stained eyes of Christ and Evangelist alike, according to whatever laws concerning icons seagulls and pelicans possessed.

With sand in my ears I remembered, with difficulty, pressing my cheek against the cool little stones, against the face of God, half in darkness beneath a towering window. Then, my feet knew the way to the tomb of Nestorius, to the hard, cold shadows there, the font with its porphyry rim. It all swam in my head, sloshing like a tide, as if I were full of the water that had abandoned this place. I remembered horses racing in the Hippodrome dust, an Empress’s hair plaited in gold.

But if I am honest, most days, I couldn’t even remember the taste of that quince-wine. I lay on the deck and tried to die. Perhaps God had simply taken pity on me, and erased quince from the face of the world, so that it could not hurt me to know how far I had strayed from any branch heavy with rough-skinned fruit.

Thus I lived on the sea of sand, in fear of storms and more mice. I ate my monk’s habit, too, after the sail was gone. It tasted only of myself, my own sweat and sickness, and I was wracked with it for days. But the bone-bare ocean was not entirely without pity. After some indeterminate number of days and leagues, the waves began to spit spectacular fish up onto the decks at dusk, sinuous beasts with long, twisted horns and scales of sapphire and gold that I had to chip from their skin with the chisel of the poor, dirt-drowned carpenter. The fish-skins clattered to the decks with tinny, tinkling sounds, and all the corners of the qarib glittered with piscine corpses. I gouged out their wet golden innards, soft as water. Under the scales and gleaming livers I found the sweetest possible flesh, delicate and translucent as moonlight. I drank the blood of the sand-fish through tortured lips, slurping the cool, raw meat from their knobby bones.

Not long after the advent of the fish, the ship learned to speak.

The Flesh may die, but never the Word, not even the Word in the Flesh, whispered the mouse-hewn holes in the mast. The sun blazed through those holes like a seraph’s many faces, and I listened obediently to all their sermons. After all, the ship spoke words I knew so well, somewhere deep in my desiccated stomach: the holy writ of Nestorius, condemning the Catholic heresy that Christ was one, indivisible entity, an ugly idea, both preposterous and obscene.

When I was a young man in Constantinople—was I a young man in Constantinople? Was I ever a young man? In my mind, the summers there stained thousands of blue silk beds black with sweat, and I cooled myself in the halls of the order of Nestorius. The incense made me giddy, the incense and the droning voice of the diakonos wobbling around my ears like a bee flexing his wings. The mosaic floated above me, the pebbled veil of Mary in her floating mandorla like a sea-ray, alien and gorgeous. Her rough mouth seemed to twist in the smoke and show blackness beneath, blackness to the depths of her, where there had never been light, only a child, his umbilicus fat and veined.

The Flesh may die, but never the Word, not even the Word in the Flesh, came the phlegmatic voice of the diakonos. Mary’s lips contorted above, wide as a fist. She seemed to speak only to me, into the bowl of my heart: The Logos is perfect, light made manifest. It is the Word of God. You must see it in your mind suspended upon the Body of Christ, a lamprey affixed to the flank of a shark. I laughed at the image then, my voice high and ridiculous under the dome, and Mary clamped her mouth shut.

I had a son, Mary seemed to whisper tightly, warped by the summer heat and the scented smoke pressing her cracked stone cheeks like bellows. I felt dizzy. I had a son like any other son. Is it my fault the Logos loved him? That the lamprey held him tight?

They took that mosaic down in the winter, when the new Patriarch took his mitre and announced that icons were the work of demons tempting us to worship stone and paint and gold instead of the ineffable substance of Our Lord. I remember the smells of the new image-less world as if they were paintings—winter lemons washing the air with their peppery rinds, the sea crusting the streets with salt. I wept, in private, for the loss of my Mary—but they brought her back just before I took my vows, when the old Patriarch died and the new one changed the game once more. Seagulls cried out above bloody Basilicas as the icon-breakers were shown the error of their doctrine, and everyone was free to make wretched, lopsided paintings of God again. It was exhausting. But Mary’s black eyes burned at my back as I repeated my holy vows. She said nothing, her stone lips pursed and thin.

The Flesh may die, but never the Word, not even the Word in the Flesh. The mast whistled in the wind, and its voice was not the voice of the old diakonos, nor Mary, but something else, raspy and pale and harsh. I snarled at it, shaking, fresh sand spattering my beard, but the dome of the sky was unmoved. I begged it to be silent, and it laughed, a shower of sunbeams scattering over the deck.

In this way did I keep myself from the despair of the sailors who bore me to this waste: I tended to Mary-in-the-Mast like a fresh-shaved novice. I ministered my parish of golden fishes. John, salt-spackled and wind-mad, kept his church. I cried to the sands and promised the life within that I would not falter, would not forget, and perish quince, Mary, Constantinople, forever from the Earth. The sea did not answer, but I feared that soon the fish would begin to speak as well, and their voices would be like horses snorting and thundering in the Hippodrome, scrabbling hooves rounding bronze tripods as they draw so close to the end.

It became my habit to fashion a blue cross each morning from the horns of the sapphire-fish, lashed together with their ropy, golden intestines. The sea of sand was unwilling to tolerate this new divinity, to allow its lone mendicant friar to consort with any other deity but itself. When the moon clattered like alms in the cup of the sky, the waves tore down my poor, wet cross and were satisfied. In the mornings, I set it up again, and said my prayers. But as the suns and moons rode their tracks, I began to lengthen my salutations, so that in addition to my phantom rosary, I would recite the names of all the churches of Byzantium I could remember. For if God could remove quince from the cosmos for the sake of His lost servant, what might He do to that half-imagined painted city of domes and mackerel? With my hair knotted back and my red skin bleeding, I called out to the whistling mast: Holy Apostles! Sergius and Bacchus! Theotokos Panachrantos! Christ Pantokrator! John the Baptist! Theodoroi! Theodosia! Euphemia! John of Studius! The Myrelaion! And Hagia Sophia, oh, the Sophia!

In time this seemed not quite enough to keep God from cupping His Hand over Constantinople and raising it out of the Bosphorus of my heart like a dripping fish-heart plucked from the world. The streets and alleys and grocers faded from my mind, scratched out by sand. So I began to add the names of all the people I had known, the presbyters and diakonoi, the scribes and fishermen, the dancers and date-sellers. Damaskenos with your damned bee-voice, Hieronymos whose hand was so tight and clear on the vellum, Isidora with your sweet kisses, Alki of harborside, your swordfish blue as death! Niko who sold artichokes with tight green leaves armoring their hearts, Tychon who drank fennel-liquor until he vomited after evening services! Pelagios with such a voice, Basileus the eunuch, Clio with her belts of coins, Cyprios with his seven daughters! Phocas made beer and Symeon was a calligrapher, but his wife could not read. Iasitas was the man to get your lettuce from, and old Euphrosyne sold linen that would make you cry to touch it. And Kostas, Kostas, with your black hair shining, you sat on the wall with me, and the quince was sweet.

Soon my devotions spanned sunrise and sunset like a bridge. I held to my fish-cross at night, and the sand threw itself upon my helpless flesh instead. I wept against the hard horn crossbeams, but the desert tide had wracked my eyes of all moisture. I sobbed empty and hoarse against the waves, and began again my litany of churches and apricot-sellers.

But each time the moon went dark, I lost one of them; a Basilica with tripartite windows snuffed out within me, a distiller of lime-liquor scooped up and away. I thought in those days that the sand would never cease, that in this world there were seas that had no end.

The flotsam of jeweled fish crammed the decks of the Tokos, scales spilling out onto the salt-surf. Rheumatic Euphrosyne and the emerald reliquaries of the Myrelaion had gasped their last and dissolved from my desiccated mind. It seemed to me then that there had never been a soul aboard but my own and those tiny, squeaking spirits of the storm-brought mice. I had not been able to close my eyes for days. Sand filled all the creases and ducts. I wept sand; I breathed it. Had there been a captain, I wondered, before me? Had there been a man with a green belt and a young wife in Cappadocia, whose hair was a most extraordinary yellow? Had he known a song about St. Thomas? Had he knelt in horror at the feet of the navigator when the blue and cheerful sea turned to sand? I could not tell, I could not tell.

Folly, I assured myself. No man knew this ship before me, it was impossible—yet I seemed to remember a green belt drifting on the golden eddies. I could not be sure.

The Word Dwells in All Things, whispered the mast, the Word in the Quince, the Word in the Mouse. The Logos of the Sand. Mary-in-the-Mast, John-in-the-Ship—the Word in the Flesh.

“Leave me alone,” I said. I could not close my mouth, with the sand so hot in my jaw.

Listen, John-my-Grist: Christ, the Shark, and the Logos, the Lamprey, hummed the lacerated pillar. Go into the Sea, Trust to the Sea, Breathe the Gold of the Earth and Fear Not. In the Depths, the Lamprey will Find you, and you will know It by Its Teeth in your Side.

“I am afraid,” I said, clutching my blue-horned cross before me.

I will take the Sophia from you, hissed the mast, with its great bronze dome. I will take your Purpose, what you came for, to find the Tomb of St. Thomas and glory for your Master. And I will take Kostas on the wall. Be my Shark, John, and I will be your Star-of-the-Sea, your Star-of-the-Sand.

“No,” I whispered. My hands shook terribly. “I need them.”

Be my Shark, be my Endless Swimming.

I clutched my cross to me, glancing back fearfully at the stern mast, its mouse-mouths grinning. The sun seemed so bright, bright as the sugary wine in my friend’s brown hand as we sat on the wall and discoursed as the fishing boats came in, his gentle voice chiding: John, surely the nature of Christ is vast enough to encompass all of these things, the Logos and the poor lost boy and the Dove moving in His breast. Surely we are all vast, and He, the greatest of us, cannot be less than you or I, who are made of light, and still suffer in our flesh. I clung to his voice, receding down the darknesses inside me, the memory of Kostas, ever wiser, ever more gentle, growing weak and dim, his echo coming before his words, dissipating along the rim of my heart until only fragments of his whispers floated unmoored in me: vast, vast, vast.

I could not even close my eyes to leap; the sand had wedged them open with fire and pain. But leap I did, and the wind made no sound when I landed—hard—on a solid spit of sand. I stood shakily, my eyes scalded, my cross bent irreparably.

The mast laughed with all its hundred broken mouths, and the Tokos rode on in the glare, across liquid dunes, unmoved by the loss of her last man.

I, John, lately of Constantinople, began to walk East, as though a star ever rose in another direction.

THE CONFESSIONS OF HIOB VON LUZERN, 1699

My candle-of-the-hours had dripped its way down. The nail I had set between the seventh and eighth marker clattered onto its tin dish, and I started from—dare I say such a thing?—John’s chronicle, John’s book, his own hand and thoughts. I could not help but believe it genuine. This was certainly bad scholarship, but faith and hope are inarguable virtues. I believed it; it was so. Where my unworthy fingers had pressed the corners of the pages, brown blemishes rose up, as on the flesh of a pear left out too long. I trembled, with that unnamable emotion that only those men devoted to books and letters know—to come so intimately close to that which I had studied so long, with passion and sleeplessness and cramped hands.

I set aside the golden book, my back stiff and aching with the effort of copying. Such work I had not done since I was a youth, struggling with my rosa-rosae-rosam and my tripartite God and my lust for certain city girls who, even if my mother had not promised her sons to the Church, would have been far out of my reach, their round, milk-colored bodies swaying down other roads, toward other men. I have boys to scribe for me now—for I have often and in secret thought that it is boys’ work, to copy and not to compose, to parrot, and not to proclaim. Out here on the edge of the world I feel it safe to confess, my Lord: I once wished, and still do, on some idle occasions, that there had been wealth enough in my family to give me a poet’s leisure, to fill my days with wine and quills and all those women with their braids bound up so tightly, so terribly tight I thought it must hurt them so, and how much more lovely they were to me then, suffering the passion of their beauty. Young Hiob, in his garret, with his sonnets whirling like starved angels in the snow-motes of some sweet Alpine November—he would have entertained a cheese-merchant’s daughter on each arm, and with his toes scratched out such verses as to give Chaucer a good thumping.

But that impossible Hiob would not have journeyed so far, to the grey and red and thirsty land of Lavapuri, or seen the lady with the downy arms, or held the book of Prester John in his old, spotted hands that never touched so much as one cowherd’s girl. He would have been abandoned of God, and possibly have written verses more concise and less meandering than this old man’s babbling. Yet I fancy that the Lord my God is the most elderly grandfather of us all, and is perhaps comforted by hoary chatter and reminiscences—after all, He sometimes longs to share His own.

I found myself disturbed by the strangeness of John’s words, so riddled with baleful ghosts of the Nestorian heresy, and darker things still. All men know Christ was one being, united in Word and Flesh, the Divine Man, who walked among us so briefly. I did not like to think of John as a heretic, subscribing to that mad false prophet Nestorius and his confusing philosophies, slicing Christ down the middle like a joint of meat. Word and Flesh, separate, struggling one against the other? It is an ugly thought. It was always an ugly thought. I did not wish to send back word that I had found the great king, only to have him repeat the Devil’s own lies. Even less did I enjoy the thought of his friendships with half-literate Turkic cobble-rats. I shook my head to clear it in the close, damp cell. Hiob, you old rooster, have you not yourself been as close as kin to your own scribes and novices? Have you not embraced them with fatherly love, frankly and without judging their poor parentage? If boys came to you uneducated, did you not take it on yourself to do the work of making them wise? I passed my hand over my eyes. They should have sent a younger man. With less fog in his pate. With more hair on it, too. I called one of those dear and gentle novices to me, and bade him fill me up with bread and that runny cheese they favored here and also something fortifying to drink, even if it be full of spices whose richness endangered both my soul and my digestion.

There, there, belly of mine. Be peaceable. I look after you, don’t I?

I took up the scarlet tome, with its embossed eyes staring, staring, pricking up my marrow with their gaze. It possessed a bloody scent, lurid, like a pomegranate, or bubbling sugar, or beer when it is still so sweet, and the yeast bellows up from the barrel, soft and thick as skin.

I reminded myself: when a book lies unopened it might contain anything in the world, anything imaginable. It therefore, in that pregnant moment before opening, contains everything. Every possibility, both perfect and putrid. Surely such mysteries are the most enticing things You grant us in this mortal mere—the fruit in the garden, too, was like this. Unknown, and therefore infinite. Eve and her mate swallowed eternity, every possible thing, and made the world between them.

But oh, those eyes, they did hound me, and I feared them.

THE BOOK OF THE FOUNTAIN

an Account of Her Life

Composed by Hagia of the Blemmyae

Without Other Assistance

When I was born my mother cut off her smallest finger and treated the skin with a parchmenter’s oils. She stretched it on a miniature frame of hummingbird bones, making a tiny book in which she recorded one word for each year of my life with her—the tiny pages left room for no more. It was a strange thing, a little horrible, but I often asked her to take it down from the shelf so that I could look inside it. Hagia, it said on the first page. Cry, on the second. Lymph, on the third. Silence, the fourth. I did not understand. But I understood the tenth page, which said Fountain in Ctiste’s tight, angular hand. No child could mistake such a word, written in such a year. I would go to the Fountain, and I would drink.

My mother tied red skirts below my mouth and, though I protested, buried the little book she made me in a patch of wet, cakey soil ringed in henna bushes. I wept and scrabbled at the dirt for my book, but she would not be moved, and she had buried it deep. With red eyes I clung to her as we walked together over the Shirshya fields, past our donkeys and cows, past the skin-trees waving, past the brindles and reds and whites.

As we walked, I considered my life, as solemnly as a child may weigh her slight ten years in the world on each of her small hands. Our family tended groves of vellum-trees, sprouting out of the earth with bark of gold leaf, their boughs bearing strips of pure skin, translucent and wavering in the peppery wind. Each year, when the harvest lay stretched on hoops in the fields, tightening in the sun, we would cut squares of skin from our dumb, mute beasts and bury them in the earth to sleep until spring: donkeys, calves, camels. Up their skin-trees would come when the winter released the soil: white skins for scripture, brindle for scientific treatises, red for poetry, black for medical texts, dun for romances. Spotted for tragedies, striped for ballad-sheets. The skin of each shows differently when it is stretched and treated and cut, and we knew how the infinite gradations of literature may be strained and made more perfect through the skin of a cow.

Despite my muscular memory, which may easily lift both my mother’s laugh and my husband’s psalms and still have strength for my own long-buried desires and soliloquies, despite the coming darkness and the urgency of my pen, this thing beneath my hand is a difficult book to write. I have been all my life a scribe. I have personally translated and copied the works of the Anti-Aristotle, Artavastus, Catacalon of Silverhair, Stylite the False Lover, Pachymeres-who-spoke-against-Thales, Ghayth Below-the-Wall, Yuliana of Babel, and countless catalogues of poisons, harvests, sexual adventures, and pilgrimages to the Fountain.

It is strange. I have forgotten when we began to call them that—pilgrimages.

I have copied out the great works of our nation in ultramarine, walnut gall, and cuttlefish. Very occasionally, for the most precious volumes, I have crafted my own tincture of zebra-fat and mule-musk, the soot of frankincense and errata pages, and tears. It is this last I use now, though I thought for a long while that something humbler might be best, as I do not consider myself an author, and therefore cannot expect to be allowed to use the finer tools. But in the end, as I attempt, with clumsy but earnest need, to compose and not to copy, perhaps the quality of the ink will stand in my place, and lend some small beauty where I, of necessity, must fail.

As I write, it is morning in New Byzantium. I am comforted, as I have always been, by the scrape of quill against parchment, something like the scratching of chickens in dust—it seems full of tranquil meaning, though the next dancing rooster shall erase the work of all those white and fluttering hens, and the next scribe with her pumice stone will someday take up these pages and make room for a decade’s record of the Physon’s chalky inundations. I am not entirely at peace with this. But I shall have my comeuppance and must be sanguine in the face of it—for I have scoured my own healthy share of careful calligraphy from donkey-skin. It is the natural life-cycle of literature, whether I like it or not.

I live now in a red minaret whose netted windows let in a kind of glassy light, cut by palm-fronds and the tips of quince-trees into fitful scales of shadow, scattering this stack of neat lion-skin pages. My friend Hadulph cut them for me with much solemnity out of his uncle, who fell into a chasm and spilled out the gift of the Font into the dust. Hadulph’s claws were quite sharp enough to the task, but he wept, and the pages are spotted with feline grief. This is not, I think, unapt to my tale. When my pen passes over the stretched and chalk-dulled tracks of my friend’s tears, it goes soft and silent, and so must I.

In truth, I do not rightly know where to begin. I want to speak of my childhood; I want to speak of those terrible events that occurred when I was grown. In my head, in my heart, it all happens at once, one moment lying on top of the other, a palimpsest of days. But that is no way to write a book, and if it is a choice between beginning with him or beginning with myself, I must turn my back on the shade of the man who was once my husband and abjure his usual assumption that all things in the firmament are primarily concerned with his person. I am sure he will be affronted; I feel the wind off of the persimmon groves chill and bristle.

Quiet, John. Quiet, my love. The world existed before you came. We lived; we ate—we even managed to laugh and have a few children before we knew your name.

Bells ring low and sweet in the al-Qasr. It will be warm today, and the wind will bring roses.

When my mother took me to the Fountain for the first time, when I was ten years of age, I felt nothing in the world could be hard or cold or implacable. These days we would call our long walk a pilgrimage, but I did not know the word pilgrim then. No one did. What could such a thing possibly mean? But I knew that my mother was called Ctiste and that she had a waist like a betel-tree and high, small breasts tipped in green eyes like mine—for the blemmyae carry their faces in their chests and have no heads as men do. But we are capable of beauty, whatever you will hear men say. Ctiste was beautiful, and I loved her. I remember her best bent over her parchmenter’s work, and so too my father, working the hoops of laurel wood outside our house, fragrant and white, stretching piebald skins over their curvature. My parents set the pegs true under boughs of champaka flowers; pale orange shadows flitted on their long, muscled arms, the mouths in their flat stomachs no more than hard, thin lines.

I held her hand very tightly as we walked from the city—for you must always walk to the Fountain. If your feet are not road-filthy when you arrive, you have not suffered enough to be worthy of the water. My mother was very strict about this, stopping every few miles to rub red, clayey mud onto the soles of my bare feet, in case I was not sufficiently squalid. The Fountain bubbles and flows quite far from what is now Ephesus Segundus—then sweet, gently dilapidated Shirshya, where no one wrote their name without touching my family, our work, our skin.

The Fountain-road astonished me. Such an extraordinary thing for a child to tread. So long, so bright, so loud! Tight as a girl’s hair it curled northward from Shirshya, cutting through fields of spiky kusha grass like brown bones. Pink-violet lotus floated on pools of white sand like lakewater, pale green leaves tucked neatly up beneath their petals. Around her ample waist my mother had tied a belt of books for barter; the spines and boards thudded dully against her hips as we walked, and the smell of the dry grass smoked the air. Ctiste wore red, too. We all wear red on the pilgrim road.

A road can be a city, no less than Shirshya, no less than Constantinople. The Fountain-road formed a long, wending capital—we must all walk it, and so it became our own sweet home, no matter where we were born. Every mile was occupied as firmly as war-won territory, by lamia selling venom and lemon cakes, by fauns selling respite in their arms, by tigers selling tinctures of their claws and eyelashes, by gryphons selling blank-faced idols of chrysolite and cedar. The turbaned tensevetes, their flat, frozen faces gleaming, let their cheeks drip and melt slowly into amethyst vessels, which are then sold to the peregrinating multitudes as holy and magical draughts. At the time we thought them charlatans, but now, when my journeys Fountainward are long done, I think on those cerulean hermits and suppose they never did lie. They let their bodies flow out to ease the throats of the faithful, and that is holiness true, even if it was never more than water. We drank those purple phials; we paid the sharp-toothed tensevete with a novel about a river of ice flowing deep within the earth, peopled with the ghosts of jewel-divers who lived upon the pearls that line the river-floor, feasting on them in misery. It was written on silvery sealskin, and clasped to Ctiste’s belt with an ivory buckle.

At night, the road stretched on forever, up into the mountains, lit by countless lanterns, a thin, spiraling line of lights, moving slowly in the mere, buffeted by gentle laughing and gentler singing. The lotus fields turned to turmeric and coriander, wide and green, and the sharp, fresh scent wound among our silver lights, wound among the shadows, wound among a thousand and more arms swinging in time to a thousand and more steps. Where the land grew rocky, we helped each other climb—a man with stag’s horns and a chest thin as balsam lifted my mother onto a high ledge dotted with shoe-flowers, glinting wrinkled and red in the dark, and placed me beside her with a chaste wink. I carried a bronze-eyed woman’s child for several miles, pulling the girl’s braid and telling her stories about headless heroes with stomachs like beaten brass.

When the turmeric died away, and the rocks grudgingly allowed only moss and the occasional lonely pea-plant, we came upon a cart owned by an astomi, her gigantic nose twitching to catch the faintest aroma on the wind, her prodigious nostrils grazing her own breast. Her cart brimmed full of the most extraordinary wares—at least to the eye of a girl who had seen only parchment-trees and the Shirshyan toymakers’ wooden baubles. The cart-woman’s nostrils shone; astomii have no mouths, but eat scent from the air itself, sniffing apples and turmeric and girlflesh with abandon. Ignoring my impatient mother, as a canny merchant will, she showed me a miniature model of the universe, no bigger than a walnut, impossibly intricate, all in gems dredged from the Physon’s glittering inundations.

“The crystalline spheres,” the astomi said, her voice coming pinched and nasal from the vast tunnels of her nose. “With Pentexore at the center, bounded by her sea of sand—rendered in topaz—and ringed in jeweled orbits: opal for the Moon’s circuit, gold, of course, for the Sun, carbuncle for Mars, emerald for unfeeling Saturn. The cosmos on a chain around your neck—excuse me, charming blemmye, your waist—and, if you’ll allow…”

She turned a tiny silver key in the base of the device, and the spheres began to click and whirl slowly around the plain of Pentexore, where I could make out a thin sapphire river and specks of carnelian mountains like pin-heads. Oh, how shamelessly I begged for this thing! How wickedly I wheedled! But Ctiste was merciful, as indulgent as any mother on a holiday. Quiet as ever, and more patient than I deserved, she unhooked a volume from her belt: a dissertation on the matriarchal social structure of the scent-farmers of the plains, bounded in bone boards, and into the bargain the astomi threw a little ring of lapis and opal which my mother slipped over the stump of her severed finger.

I wore the cosmos on a belt around my waist. Even now as I write, it dangles in my lap like a rosary, and the slow clicking of the spheres calms me.

I fear this must be tedious: any child in Pentexore could tell the same story, describe the same road, the same lanterns, the same trinket-bearing nose-maiden. There is comfort, there was always comfort in the uniformity of our experience. Yes, my child, says each grandmother, I walked that road, my blisters pained me just the same as yours. I saw the line of lights; I broke my feet on the same boulders.

John, too, walked this road, our dilapidated priest—do not believe otherwise, no matter what he assured certain of his own folk. Who does not elide their private matters in the presence of family? But no—no matter how his shade rattles the quince for attention and demands I perform as graceful amanuensis for his gospel, this is not his story. It is mine. He cannot have this, too.

The air of the Fountain howled thin and high, blue as death, giddy. A rock-table wedged itself in the ring of mountains like a gem in a terrible crown, and in the rock-table sunk a well, deep and cold. The table allowed room for only a few folk at once on that narrow summit. Just as well, for each creature’s experience of the Fountain remains their own, uninterrupted by the rapture of another. Thick, grassy ropes edged the last stony paths, so that our lives might not be entrusted to disloyal feet. Clutching these, clutching the rocks themselves, we climbed, we climbed so far, by our fingernails, by our teeth, panting in the ragged wind. The silence loomed so great there, so great and vast, wind and breath alone polishing the faces of the mountains. It was hard. Of course it was hard. All pilgrimage is difficult, or what use would it be?

I crawled up into my mother’s lap and laid my thin chest between her breasts as we waited for our turn. I felt her lashes on my shoulders; the wind beat at us with both fists, the ropes swinging wildly below. Finally, hand over hand, our red skirts snapping against our legs, we balanced on the thinnest of rock-spindles, our toes sliding off the shale into the ether, and we crossed to the well, to the Fountain.

Apples grew there, withered and brown, branches tangled in the masonry of the well. The stone snarled like ugly, purpled roots chewing their way out of the ground to make a vaguely well-shaped hole. I thought it looked like the mountain’s mouth, sneering at me, grimace-twisted. The apples slowly swelled as I watched them, thickening red and fat and glossy, huge as hearts, even budding a glisten of dew. Then they shriveled again, extinguished, sallow and past cider-making. As I ran my fingers over their soft, rotten faces, they began to rouse once more, billowing up hard and scarlet. They stuck through the cracks of the well like tongues. Ctiste ignored them and knelt by the well where the Oinokha sat, a woman in scarlet wool with a swan’s head undulating out from her thin and narrow shoulders, her feathers buffeted by the winds.

The Oinokha pulled me forward and fixed my hands to the twisted blue-violet stone of the well. I looked within—and the roots of the mountain twisted in the pool like jealous fingers, still and sharp and violet-grey, pulling the water away from a thirsty wind. The Fountain was a low puddle in a sulking, recalcitrant cistern opened up in the crags by a hand I could not imagine. The water oozed thick and oily, globbed with algae and the eggs of improbable mayflies, one corner wriggling with unseen tadpoles. It glowered, bracken-green with tracks of brown streaked through it, unmoving, putrid, a slick skin of frothy detritus over water which had sat motionless for all time at the bottom of a dank hole.

I had imagined the water would be so clear, clear and clean as a gem. I thought it would be so sweet.

The Oinokha put her hand over mine, the palest hand I have ever seen, as white as if it had been frozen, and her blood turned to frost. Her fingernails shone black.

“Somewhere very far away,” she said, her voice playing underneath the wind like a violin bow caught up in a sand-dervish, “a mountain rises out of a long, wide plain and an ocean of olive trees. Clouds as white as my thumb cover its peak. On top of this mountain lives a crone in a pale dress that falls around her body in crisp folds, like marble cut into the shape of a woman. She lives alone among eleven broken columns, and her eyes shine so clear and grey, grey as the tip of her spear, grey as the feathers of the owl that lives in the place where her neck curves into her shoulder, his broad, breathless cheek against hers, talons always gentle on her collarbone. I know her—she likes her olives a little under-ripe, so that they slide hard and oily beneath her tongue. There are people who call this mountain Olympos, but they do not guess that mountains have roots like trees, and the purple stone of Olympos reaches under the earth to join with the gnarled, senescent root-system of volcano and sea-drowned range, foothill and impossible cliff. Under everything, they knot and wind, whispering as old folk will do, chewing darkness like mint-leaf and grumbling about the state of the world. Olympos is far away, my child, but she splays out here, like an oak whose smallest root humps up a mile from any acorn. Sometimes, when I press my head to the stone, I can hear the crone and her owl spitting olive pits at little laughing rills.”

The Oinokha gripped the roots with her strong, pale hands, and bent her head into the well. I could not breathe—I had never seen a meta-collinarum before, the swan-maidens who stayed so private and silent when, rarely, so rarely, they graced Shirshya with their swaying steps. Her feathers puffed and separated in the wind as she pecked at the apple-leaves with a flame-bright beak.

“The same people who know the name Olympos,” the swan-woman went on, “say that there was once a dark-skinned girl named Leda who loved a swan—and who among us should judge the habits of foreigners? They say she bore two sets of twins, two daughters and two sons who burst out of eggs dripping with yolk like liquid gold, and between the four of them they broke the world on their beauty.” The Oinokha smiled, as much as a swan can. “But my friend who piles up olive pits among the columns whispers to me through the mountain-roots that Leda had a fifth child, who did not have the beauty to fill out recruiters’ rolls, but the head of a swan and the body of a woman, a poor, lost thing, alone in her egg, without another heartbeat to keep the beast in her at bay. Her sisters loved only each other, and her brothers loved only bronze swords, and so she wandered into the desert, away from her family’s burning cities, to the end of the world.”

The Oinokha turned her arched neck to me, and a tadpole caught from the masonry wriggled helplessly on her bill before she slurped it back.

“Why is the water like that?” I asked, bashful, trying to retreat behind my mother’s skirts.

“What do you expect a mountain’s blood to look like?” the swan replied.

My mother laughed gently. She reached just behind her left hip and unbuckled a book—a compendium of the traditional mating ballads of the seabirds who lived on the edge of the Rimal, the dry sea that hurls its sandy waves at their nests on golden cliffs. The Oinokha took it shyly, her eyes glistening. She ran her icy hands over the feather-stalk spine.

“Such riches!” She pressed it to her breast. “It is so tedious here, with nothing to read!” she chuckled, and reached for a stone ladle, stained by countless circuits through the water. And I understood why she had told me about Leda—a trade, a story for a story.

I did not want to drink from the Fountain—it smelled like peat-wine far past wholesomeness, and my throat closed against it. But suddenly white, downy hands pressed my face, and my mother’s dark mouth whispered soothingly against my shoulder. I squeezed my eyes and lips shut, but between them they coaxed open my mouth. The Oinokha lifted a brimming ladle and I am ashamed to say that I choked on the sacred waters of the Fountain. My body did not want it; my tongue recoiled at the over-rich taste of earth, thick and dank, and several slippery, too-green lumps of algae like phlegm rolling over my teeth. I choked—it was not at all seemly, and they held me while I spluttered and spilled it onto my pretty red belt. The Oinokha laughed; a tight, fluted sound from her slender neck.

“I choked the first time, too,” she said kindly.

There are no more journeys to the Fountain, and the turbaned cart-masters are gone. No more graffiti on the mountain walls extolling the truth of it all: pilgrimage is long and monotonous and we do it because we must, as children wash the sink. If there are ropes still atop that mountain, they wave in the scentless wind and help no one to cross the chasms.

But I drank there, and so too did all the folk of Pentexore until after the war. After John. We drank at ten, at twenty, at thirty, the great pole-marks of our lives, and once we had forced down a third draught of sickly, fetid, fecund water, we aged never after, and never died save by violence or accident; and this is not so terrible a trade for three long walks and three foul swallows.

THE CONFESSIONS OF HIOB VON LUZERN, 1699

I wonder sometimes what the memory of God looks like. Is it a palace of infinite rooms, a chest of many jeweled objects, a long, lonely landscape where each tree recalls an eon, each pebble the life of a man? Where do I live, in the memory of God? When Your great triple Heart turns to me, where do You look?

Do you remember, Lord, when I was a boy, and my father ordered me to assist with the birth of that calf? How are child’s prayers ordered in Your sight?

I did not like the cows. They stank, and nipped at me wickedly as if they sensed and shared my distaste. What pot, said my old father, you like milk and cheese well enough. Nothing you make of your body is half as sweet, yet we turn up no nose at you.

Truthfully, my contempt for the farm was no fault but his. Since I was a babe my mother had told me I was promised to God, and upon my twelfth would be delivered to You. What should I care for cows, then, knowing the comfort of a monk’s bed and the gentle work of paper and ink and prayer and song were to be my vocation? If one morning had risen fresh and pink to reveal all our cows lying dead on the frozen field I would have rejoiced. I have no shame left on it: I was a bad son.

But my father dragged me anyway, out to the stable with the cold cracking like broken bones, and the stars overhead so bright and sharp and white, streaked with milky, diaphanous mist. Take me now, God, I prayed silently, sure You would Hearken, as I was Your promised child and so specially loved.

The heifer lay in her straw, mewling pitifully and glaring with spite at myself, a little furry ear sticking out of her rear. But there was much blood, and other fluids besides that I dared not guess at, the secret wetness of women, be they cows or angels. But my father could not content himself to let me watch and learn and quickly forget the whole affair. He got me into the great beast up to my shoulders, hauling at the calf. The hotness of her pressed all around me, the smell buffeting me, barnyard and blood and fear. I could feel the calf in my arms, its complicated bones, its hooves and its ribs, and my skinny arms wrapped around it, pulling, weeping along with the mother as she lowed. Finally the babe came free, and I fell back with a huge lump of cow and blood and white mucus in my arms, so sopping I could not even tell where its eyes might be. My father righted the creature and scooped muck from her eyes with a tender grin such as he never had for me—for it was a heifer, and that meant good milk and breeding with my uncle’s brown bulls.

“Life is like this,” quoth my father. “Ugly to begin with, ugly to end with, and hard to manage all the way through.”

The girl-calf wobbled on her new legs in a way I suppose others might find endearing but I saw only as a clever attempt to curry favor with humans. I refused to love it. The creature plopped herself down in my lap and proceeded to fall asleep while my father tended to the mother, whose privates were torn and miserable. And as I sat there with the calf snoring lightly against my knee, I could not help but think of the Christ child, and His birth in the hay and stink of what was surely not a very clean barn. Was it like this, I thought? Did Joseph or some other poor country midwife struggle against the close hotness of Mary, hear her pain and smell her blood, pull the Divine king from her body like so much cow? Perhaps Joseph did not much care for babies, as I did not, and stared stupefied at the son who was not his son, and wondered how something as big as a man could grow from a wet lump of squalling?

Of course, one ought not to entertain thoughts of the close hotness of Mary, or, for that matter, of the squalling of Christ. Yet I have always considered these practical things, and wished to know not only what is written, but what it was really like, if I could have been there. If You were troubled by human ugliness and the workings of women, I suppose You would have chosen some other way to be born. Yet I wonder if I could have stood by and held Mary’s hand in her travail. Would I have been steadfast? Would I have loved a wet, unhappy child?

I am not too much bothered by cows or blood anymore. And if I could have been there when a priest called John stumbled onto this kingdom, if I could have held Hagia’s hand as she drank her strange draughts, I believe I could have been stalwart. I believe I could have stood with them. Though surely it was not the Fountain of Youth, not that oozing, disgusting mountain crevice she believed to be the holy Font. The Fountain of Youth is no such miasma—it is crystal and gold, trickling in perfect melodious harmony from dish to dish, a water pale as diamonds and as pure. All men know this to be so. But I allowed it might have been some unloved sibling of that radiant spring that sustained John’s strange and hideous wife—and oh, how my heart disturbed my chest, to think that our Presbyter, Priest and king, should have sullied himself with a spouse.

Guide me, Lord. Should I have told all to my brothers at home with their frozen feasts and their dreams of righteous rule, or concealed at least the wife, who could not be suffered to exist? Is it the historian’s part to include what is right, and excise what is shameful, so that in the future souls may be elevated by our deeds? Or is it his duty to report everything, and leave nothing hidden?

I was all full of disquiet in that long first night, as though I were even still struggling to bring forth some hoofed, toothy thing from black innards.

The last book, the small green antiphonal stamped with the sigil of a single great ear, glinted at me, its sharp, herby scent piercing the air: serrated coriander leaves and lime pulp and bitter, bitter roots. The nail had fallen from the candle. I could not afford idle dreams of cows who were now long dead and all their milk drunk. I prayed for no new surprise to dint further the golden image of the king in the East that hung still within me, like a lamp.

THE SCARLET NURSERY

Told by Imtithal the Panoti

to the Three Children of Queen Abir,

Who Were Lamis the Reticent, Ikram

the Intractable, and Houd, Whom You

Might As Well Indulge.

Here I shall set down some few of the things I told to the children of the queen during the long spring of their rearing, when they seemed to my heart like fig blossoms blowing wild in white whorls around me. I shall also speak of my own love and thoughts, for no tale can be believed if the teller is a stranger to the hearer. Let it be known that in that life I was called Imtithal of Nimat-Under-the-Snow, but the children called me Our Butterfly, because I slept with my ears wrapped around me like a cocoon, disappointing them when I emerged each morning still their old nurse, without spectacular violet wings or antennae tipped with emeralds. Of course, it is part of the duty of a nurse to disappoint her charges as often as possible. Children must practice disappointment when they are young, so that when they are grown, it will not go so hard with them. It is the hope of this small being that these tales might form a long rope, connecting me to those long-grown children. I loved them, and where they have gone now I cannot say. That is what happens with children—they leave you. It is a kind of heresy to try to pull their little hearts back from the wide world and into my arms again. Thus, I am a heretic. And perhaps those who read this book in some future summer I cannot know will also be as my children: many Lamises, many Ikrams, many Houds. I imagine you all now, and you all will imagine me then, and together all our imagining makes a kind of family of the mind. Perhaps some gentle souls read my little letters even now, already, as I am still writing them. For when a body lives forever, all of time is one thing, a single bauble hanging in the black. Perhaps, when you have finished what I now begin, I might be your butterfly mother, too.

Perhaps I might even, one day far from now, in another place, open the wings of my ears in the morning to reveal something quite other than Imtithal, and everyone who has read this will gather round me to be amazed—and Lamis and Ikram and poor Houd as well, and they will all run to me laughing, as they once did, and so will you, and we will all of us lie in the sun together.

First I shall enumerate the virtues of the most famous of my charges, and afterwards my own.

The royal family in those days were in the main part cametenna, (barring those married into the noisy brawl of them or adopted), whose hands are as huge and deft as the ears of the panotii, which is to say my own ears. One of their palms spread open could hold my whole body, though my ears would drape like silk over their fingers. I spoke softly to them, cross-legged in their great hands, while they leaned their small faces in to hear. Lamis, whose wide eyes shone orange as a tiger’s fur; Ikram, who possessed the most beautiful lips ever recorded in Pentexore, as deep a rose as I have ever seen, forever pursed as if she were kissing the very wind; and Houd, who did not love me until I had told him every story I knew. Only when I finished the last of them did he set me down on the ruby floor of the Scarlet Nursery and say: There, Butterfly. Beginning tomorrow I will love you for all the rest of my life.

How strange children are. As strange as any story I ever told.

Lamis enjoyed best the tales of how things came to be, for she could never quite believe that she was alive and everything around her was real. This may seem a peculiar attitude for a child to hold, but many think such things, and deeper and more peculiar still, but never tell a soul. How could they bear it if they, tremulous, asked after the solidity of matter over boiled bananas and lamb-hearts one evening, and the terrifying grown folk laughed imperiously and answered: How can you be so silly? Everyone knows nothing is real. And so they keep silent and try to discern by listening whether anything that keeps them wakeful and shivering in the night is true. But in time, in the dark closeness of the nursery, when all the stars have come out and the wind is very sweet, they sometimes confess to their butterfly mother.