No matter where or when a steampunk story is set, its roots are embedded in Victorian/Edwardian Britain. It gleefully lifts from that age the fogs and gas lamps, the locomotives and hansom cabs, the top hats and crinolines, the manners and—good Lord!—the language. It adds to this mix its icon of choice: the airship, which didn’t actually exist during Victoria’s reign, but which seems to best symbolise the idea of a glorious, expanding, and unstoppable empire.

All this adds up to a fantastic arena in which to tell tall tales.

There is, though, a problem.

Where, exactly, is the punk?

Okay, maybe I’m being picky. The thing is, I’m English, and I’m of the punk generation, so this word “punk” has a lot of significance for me, and I don’t like to see it used willy-nilly.

The original meaning of the word was hustler, hoodlum, or gangster. During the 1970s, it became associated with an aggressive style of do-it-yourself rock music. Punk began, it is usually argued (and I don’t disagree), with The Stooges. From 1977 (punk’s “Year Zero”), it blossomed into a fully-fledged sub-culture, incorporating fashion, the arts, and, perhaps most of all, a cultural stance of rebellion, swagger and nihilism.

Punk rejects the past, scorns ostentation, and sneers at poseurs. It is anti-establishment, and, in its heyday, was loudly declaimed by those in power as a social menace.

In many respects, this seems to be the polar opposite of everything we find in steampunk!

If we are to use the term, then surely “steampunk” should signify an exploration of the darker side of empire (as Mike Moorcock did, for example, in the seminal Warlord of the Air)? After all, imperialistic policies remain a divisive issue even in the twenty-first century.

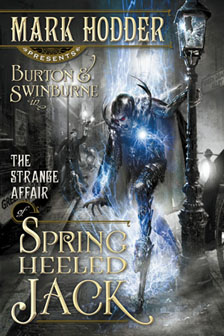

In The Strange Affair of Spring-Heeled Jack, I introduced a social faction known as “The Rakes.” Their manifesto includes the following:

We will not define ourselves by the ideals you enforce.

We scorn the social attitudes that you perpetuate.

We neither respect nor conform with the views of our elders.

We think and act against the tides of popular opinion.

We sneer at your dogma. We laugh at your rules.

We are anarchy. We are chaos. We are individuals.

We are the Rakes.

The Rakes take centre-stage in the sequel, The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man (due March 2011 from Pyr U.S. and Snowbooks U.K.). What happens to them will profoundly influence my protagonist, Sir Richard Francis Burton, leading to a scathing examination of imperialism in the third book of the trilogy.

The Rakes take centre-stage in the sequel, The Curious Case of the Clockwork Man (due March 2011 from Pyr U.S. and Snowbooks U.K.). What happens to them will profoundly influence my protagonist, Sir Richard Francis Burton, leading to a scathing examination of imperialism in the third book of the trilogy.

The point of this shameless self-promotion is to illustrate that the politics and issues inherent in the genre can be approached face-on while still enjoying a gung-ho adventure.

An alternative is to have fun with a little post-modern irony, and for a long while, I thought this was where the genre was going. In the same way that George MacDonald Fraser’s Flashman is a wonderfully entertaining character whose politics and morals stink, I thought steampunk might offer a portrayal of empires that seem golden but which, by the end of the story, are obviously tin.

Unfortunately, I’m not sure I’m seeing this. It worries me that the trappings of steampunk might become a meaningless template.

“Punk” is a sociopolitical stance, and if you use it in the name of your chosen genre, then doesn’t that oblige you to at least acknowledge that there are implicit issues involved? Remember, steam technology was at its height just before the world descended into WW1; the airship was at its peak just before the Great Depression; and here we have steampunk flowering on the brink of a massive economic crisis.

Intriguing. Exciting. Perhaps a little bit scary.

My point is this: if you adopt the steampunk ethos, then you need to do so knowingly, because it brings with it certain associations that you might not want to represent.

That’s why it’s vital that you find a way to put the punk into steampunk.

Iggy Pop photo by NRK P3 used under CC license

Mark Hodder is the creator and caretaker of BLAKIANA, which he designed to celebrate and revive Sexton Blake, the most written about detective in English publishing history. It was on this website that he cut his teeth as a writer of fiction; producing the first new Sexton Blake tales to be written for forty years. A former BBC writer, editor and web producer, Mark has worked in all the new and traditional medias and was based in London for most of his working life until 2008, when he relocated to Valencia in Spain to de-stress, teach the English language, and write novels. He has a degree in Cultural Studies and loves history, delusions, gadgets, cult TV, Tom Waits, and assorted oddities.