The term “future history” was coined for editor John W. Campbell to describe a series of stories Robert Heinlein was writing for Astounding Science Fiction magazine in the 1940s. As used in the science fiction genre, the term implies more than just a series of stories set in the same universe. The term “future history” is applied to a series that spans an extended period of time. In fact, authors of future histories invariably report it is necessary to write down an outline of the events and changes to society and technology, which occur during various periods of the timeline. Heinlein started this trend with his famous chart. Other future histories include Poul Anderson’s Technic Civilization, Cordwainer Smith’s Lords of the Instrumentality, H. Beam Piper’s TerroHuman Future History, Alan Dean Foster’s Humanx Commonwealth, and Larry Niven’s Known Space.

A Niven Reading Experiment

“Spike” MacPhee (one of this article’s authors) ran the Science-Fantasy Bookstore in Harvard Square, Cambridge Massachusetts, from 1977 to 1989, and so was able to observe people’s reading patterns. In 1977, as a new bookstore clerk, he had many duties, but also time to observe human behavior puzzles. One of these was the case of readers new to Larry Niven’s worlds, who started to explore them by first buying Ringworld. Why then did only one-third of them try more of his books? The normal author continuation rate, he had observed, was roughly one-half. How could he improve this rate for Niven?

He thought the problem through: Authors tend to build their future histories by starting with short stories and novellas published in science fiction magazines. As they gain proficiency and confidence in their storytelling skills, they move on to writing novels as they acquire a marketable brand name with science fiction book editors at the large publishing houses.

Contemporary readers delight in each new addition, both to the depth and detail of the creator’s universe, as well as the fleshing out of already-encountered characters, cultures, and events. Later readers don’t share in that organic progression of tales as the author spins them out.

An ongoing debate for readers who didn’t read each story when first published is “in what order should I read all the stories—internal chronology, or do I read them in the order written?” The answer varies from reader to reader, depending on the availability of those stories, and/or desire to follow the author’s timeline or order of creation, as well as the ease of first introduction to a detailed universe. Often, random chance rather than a deliberate decision decides how a reader encounters an author’s words and worlds for the first time: a library shelf, a short story anthology with one story by that author, a friend’s suggestion, even a yard sale purchase.

Readers tend to buy novels, rather than short story collections or science fiction magazines, by a ten-or-twenty-to-one ratio. They often enter a future history by way of a novel that makes use of an existing background that is entirely new to them. Authors and editors strive to make each story or novel self-contained, so that a reader can start anywhere and enjoy their future history. That wasn’t happening as much with Ringworld.

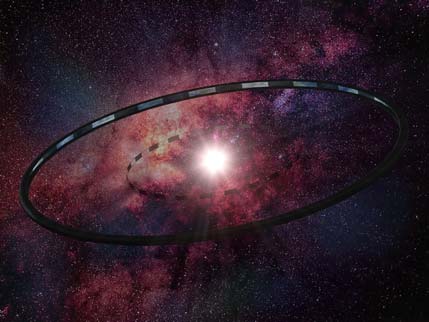

Larry Niven’s Ringworld was his third novel, and it achieved the rare distinction of winning both the Hugo and Nebula awards for Best Science Fiction Novel. So, many more science fiction fans first encountered Niven by browsing their way through the award-winning novel lists, or seeing Ringworld’s book cover proclaiming its prestigious awards, and then buying it.

It seemed to “Spike” that he should suggest to readers that they try a different Niven book first, as an introduction to Known Space. He tried out his theory: Of a sample set of about 60 or so readers, he got them to first try the Neutron Star collection before attempting Ringworld. Doing so improved the sample set’s desire to continue on to other Known Space books—from one-third to approximately two-thirds.

It seemed to “Spike” that he should suggest to readers that they try a different Niven book first, as an introduction to Known Space. He tried out his theory: Of a sample set of about 60 or so readers, he got them to first try the Neutron Star collection before attempting Ringworld. Doing so improved the sample set’s desire to continue on to other Known Space books—from one-third to approximately two-thirds.

So, if you have not yet read Ringworld, we strongly urge you to do the same. Readers trying out a new author for the first time do not usually search for an author’s out-of-print books, but we hope to persuade you to make an exception in this case. We’ll make it easy for you: Copies of Neutron Star can be found through Addall.com’s used book search.

Of course, we are not going to insist you start with the Neutron Star story collection. We promise the Thought Police will not arrest you should you plunge directly into Ringworld. In fact, David “Lensman” Sooby (this article’s other author) became a fan of Known Space by doing exactly that! But you’ll get more out of Ringworld if you read the Neutron Star collection first. (Trust us.)

The Back Story of Ringworld

The novel contains numerous references to previously published Known Space stories, which form the “back story” of Ringworld. These include:

World of Ptavvs: This novel introduces the Slavers (aka Thrintun) and the ancient Slaver Empire. It also introduces the Bandersnatchi, which also survived from that era along with Slaver technologies, i.e., stasis fields and Slaver disintegrators. Both are important technologies in Ringworld. Sonic stunners also appear in several later Known Space stories.

“The Soft Weapon” introduces the Puppeteer character Nessus and serves as a good primer on the warlike Kzinti, so important to understanding the background of Ringworld. The Puppeteer migration is described, and the Slaver technologies of stasis fields and variable-swords are explored. All of these appear in Ringworld.

“There Is a Tide” introduces Louis Wu, and tells of his first contact with the Trinoc who became ambassador to Earth, as mentioned in Ringworld’s first chapter.

“At the Core” introduces the concept of the Core explosion, central to Louis’ motive for agreeing to join Nessus’s expedition. It introduces the starship Long Shot and tells of the beginning of the Puppeteer migration.

“A Relic of the Empire” introduces various species of plants that have survived from the Slaver era, like the Slaver sunflowers, which also appear in Ringworld.

You will also find in Ringworld references to places, species, and technologies introduced in “The Warriors” (Kzinti), “Neutron Star” (General Products hulls), “Flatlander” (Outsiders), “The Ethics of Madness” (autodocs), “The Handicapped” (flycycles), and A Gift from Earth (Plateau and its Long Fall river).

But that’s not all. There are other references to stories outside the Niven canon. These include Alice in Wonderland (the Cheshire Cat and Bandersnatchi—a reference to the poem “Jabberwocky”) and Dante’s Divine Comedy, which Niven later explored with co-author Jerry Pournelle in two novels unrelated to Known Space: Inferno and its sequel, Escape from Hell.

Now, we are not suggesting that you should read World of Ptavvs and all the other stories mentioned above before reading Ringworld. But most of the relevant stories are in Neutron Star, and if you enjoy that collection, then you will then have enough background to precede directly on to the wonders of Ringworld.

A less satisfactory and narrower (but in-print) introduction to Known Space is the more recent Crashlander collection. Less satisfactory because it omits “The Soft Weapon” and a few other stories mentioned above. Worse, it has massive spoilers for Ringworld. If you do choose to start with Crashlander, we recommend you skip the framing story “Ghost,” and stop before reading “Procrustes,” until after first reading Ringworld. You’ll be glad you did!

* * * * *

More about the races, technologies, planets, places, and history of Ringworld and Known Space can be found at The Incompleat Known Space Concordance. Readers new to Known Space are encouraged to visit the “Reading Order” page. Another notable site is Known Space: The Future Worlds of Larry Niven.

Bruce “Spike” R. MacPhee is stranded at the bottom of a pointy well, and passes the time (which is flowing a billionth of a second slower than open space due to gravity affecting the local shape of space) reading SF based on physical laws or modifications thereof. Along with Jerry Boyajian and Larry Niven, he wrote the entries for the first Known Space Timeline that appeared in the 1975 Tales of Known Space collection.

David Sooby, who goes by “Lensman” online, was afflicted with an obsession with the Known Space series when he discovered Ringworld in 1972. He never recovered, and the depth of his madness can be seen at The Incompleat Known Space Concordance, an online encyclopedia for the series, which he created and maintains.