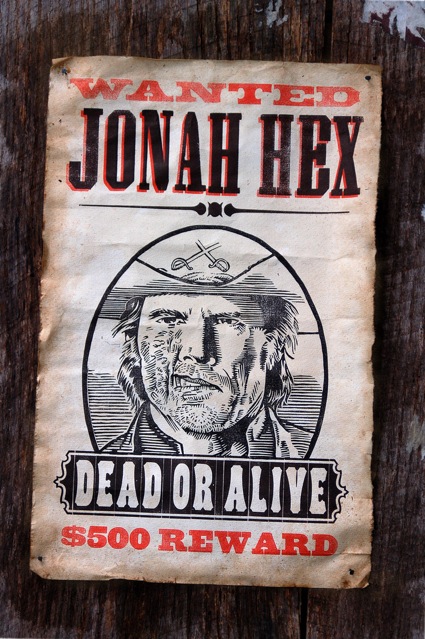

Now that the movie Jonah Hex has been in the theaters for a couple of weeks, I think it’s time to finally come clean and admit that I did some work on it. I have not yet had the pleasure of seeing it, so I have no idea if this piece made the final cut. I can tell you that Art Director Jonah Markowitz was great to work with, and I had a lot of fun with this one.

Jonah called me in March ’09, needing a wanted poster. A crew designer had already taken several runs at it, and the results were, I gathered, less than satisfactory. The one I saw was a kind of psychedelic Shepard Fairey wild west mashup. They wanted something that looked like the real deal. A friend on the crew recommended me—thanks Randy!

Jonah wanted to know a bit about wanted posters, so I told him what I knew, and soon he regretted asking…

Wanted posters are a form of Public Notice. We tend to think of public notices as “lost cat” posters these days, but originally they were much more formal documents. Think of the town crier gathering the citizens of the village and reading the proclamation from the King before nailing it to a post for all to read—that’s a public notice. A Public Notice was the law. Wanted Notices are legal contracts, and were almost always issued by a Sheriff or other duly-appointed lawman, whose name and location were printed at the bottom. If you produced the wanted person, the sheriff was legally obliged to give you the reward offered, no questions asked.

Wanted posters were mostly intended as circulars—sent to other lawmen in surrounding communities—and weren’t often tacked up all over town, as shown in most movies. Rewards were a source of extra income for deputies. However, a few posters would also be posted prominently at strategic locations—the post office, general store, etc.—in the hopes that a citizen might have information about the fugitive.

And let’s not forget the posse. Anyone who’s seen a western (and who hasn’t?) is familiar with this idea—the sheriff deputizes a bunch of well-armed townfolk (the drunker and more ignorant, the better!) and they race off in hot pursuit. A posse is one drink away from being a lynch mob, I always say.

However, the notion of the posse didn’t originate in the American west. It is descended from the “hue and cry” of ancient English common-law. The village constable or county “Shire-reeve” would raise the general alarm and order all able-bodied citizens to pursue the criminal. Instead of a reward, the people would be fined or imprisoned if they didn’t catch the outlaw. Spurred on by this, and the fact that they were legally absolved of responsibility for any injury they might inflict on the fugitive, the posse of town-folk often ran amok. Pitchforks, torches, the whole bit. Rough justice indeed! Due to the many abuses, the practice was outlawed in England around 1827, but lived on in slightly different forms in America. Posses are still a legally recognized instrument in many states. The line “dead or alive,” which—let’s face it—reads like an outright invitation to murder, really did appear on wanted posters, and is also descended from the “hue and cry”.

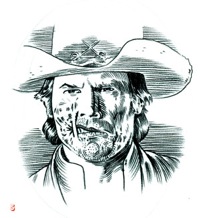

For the image of Jonah Hex himself, I did a linocut—seen here resting on my favorite work surface, the 1859 tombstone (it also serves as a reminder to stop goofing off and get back to work—tempus fugit and all that).

For the image of Jonah Hex himself, I did a linocut—seen here resting on my favorite work surface, the 1859 tombstone (it also serves as a reminder to stop goofing off and get back to work—tempus fugit and all that).

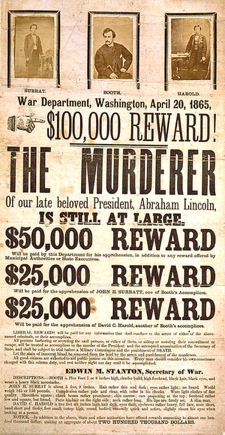

Wanted posters in the old west did not have pictures of the outlaw, due to the time, difficulty and expense of producing engravings for reproduction in those days. Many wanted posters were produced and circulated on the same day that the crime was commited and it might take days to get an engraving made. Skilled engravers were rare in the small frontier towns, so a photo—if you could find one—would have had to be sent by train or wagon to the nearest large city, and the engraving shipped back to the local printer.

Of course, movie audiences know little and care less about the history of wanted posters, and they expect to see a picture of the dude on it, dammit! This is one of those cases where it’s more important that the prop look convincing than strictly accurate. And from what I’ve seen of this movie, they play fast and loose with history anyway—Hex has a gun that shoots sticks of dynamite, for starters.

This is one of the first known instances of images of the outlaws appearing on the wanted poster. In this case, they glued photographic prints on each poster. The seriousness of the crime in this case warranted the extra time and expense involved. They used the only photos they had of the assassins—formally posed cartes de visite cards. The $100,000 reward offered on this poster would be worth about 1.4 million today.

This is one of the first known instances of images of the outlaws appearing on the wanted poster. In this case, they glued photographic prints on each poster. The seriousness of the crime in this case warranted the extra time and expense involved. They used the only photos they had of the assassins—formally posed cartes de visite cards. The $100,000 reward offered on this poster would be worth about 1.4 million today.

As railway travel burgeoned and cities became more populous, law enforcement struggled with ways of improving the description of criminals to aid in their capture. The Pinkerton Agency claims to be the first to shoot mug shots of people they apprehended. By the 1870’s, the Pinkerton archive was the largest in the U.S. Any lawman seeking information on a fugitive could wire the Pinkertons and recieve a package of photos and a description in the mail. Soon, many law enforcement agencies followed suit. After the development of the halftone process in 1880, it became quicker and easier for printers to reproduce photographs. By 1900, most wanted circulars included mugshots as well as a physical description.

|

The time period for the movie is in the years just after the civil war, the apex of wood type design. This typeface, Gothic Tuscan Condensed Reverse, was manufactured circa 1879 by the king of wood type designers, William Page of Greenville Ct. A slight anachronism, maybe, but hey—it’s a movie made from a 1970’s comic book, fer crissakes. |

|

This stuff – Grecian Antique Condensed—is old and looks it. Circa 1840. |

|

This same cracked “N” appeared on the Lincoln book cover. |

|

Extended Antique Tuscan, from 1859; and Antique, first shown in Darius Wells’ 1828 Specimens. Wells was a New York printer, who—feeling the need for larger and more robust display type faces—invented the steam powered vertical router in 1827. This machine enabled the rapid manufacture of wood type, which spread rapidly. Interestingly, Wells never patented the machine, which also allowed for the explosion of flora dora Victorian ornamental architectural woodwork.

That last typeface is part of a font—one of many—that came out of the basement of the Lizzy Borden house. |

|

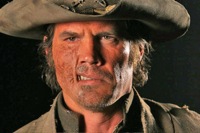

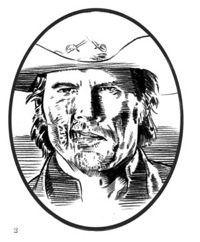

This is one of the photos of Josh Brolin I was given for reference. |

|

Initially, they wanted to try an image on the poster that did not look exactly like Brolin, but that idea was abandoned. |

|

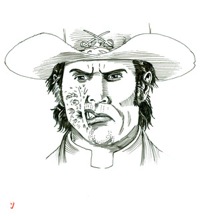

Another version. |

|

This is the drawing I used for my linocut. |

Once the linocut was done, I cranked out a few hundred copies of the poster on the Vandercook press. I tried it on several different paper stocks, but the laid paper looked best.

Like I said, the poster may not even show up in the finished movie. This one went through so many changes—the first director quit in pre-production, for starters—that it’ll be a miracle if my poster made the cut.

Now I have to watch the movie, and try not to jump up and shriek if I see my poster on screen…

Ross Macdonald is a letterpress artist, illustrator, and prop maker. This article originally appeared (and still appears, with larger pics!) on drawger.com.