I have to admit. Of all of the books in this reread (and for some upcoming books, first time read) Ruth Plumly Thompson’s Handy Mandy in Oz was the book I approached with the most trepidation. I even put off reading it for awhile, doing some other things, jumping ahead to read the next two books in the series, before steeling myself and heading back.

The reason for my hesitation: given the casual racism and embrace of colonialism and conquest in previous books, and Thompson’s avoidance of most of the Oz characters who embrace, knowingly or not, a disabled identity (most notably the one-legged Cap’n Bill and the Tin Woodman, slowly formed of prosthetic limbs and a tin body) I was not eager to read a book where she chose to create a heroine with an obviously different, even freakish, appearance. Rereading it has left me with decidedly mixed feelings.

Handy Mandy in Oz tells the tale of Mandy, the goat girl, who happens to have seven arms. In Mern, her home, this is customary and useful. As Mandy points out, she can use her iron hand for the “horrid sort” of work; the leather, wooden and rubber hands for other jobs; all while keeping her two fine white hands soft and ready to take care of her hair. (The passage gives the distinct impression that Thompson was tired of housekeeping duties.) A geyser—yet another one—sends her to Oz and yet another small kingdom with yet another missing king. Here, she teams up with Nox, a royal ox, against the Wizard Wutz, King of the Silver Mountain, who aside from kidnapping kings as a hobby is also speedily working to steal all of the great magical items of Oz with the help of his five secret agents.

Oddly enough, the spy sent to the Emerald City disguises himself as a…monk. Odd, because this is only the second reference to any kind of organized religion in Oz in the entire series. (The first occurred far back in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, when Dorothy encountered china churches in the China Country.) Given the seeming lack of organized religion in Oz, I’m not entirely sure how the citizens of the Emerald City would even be able to recognize a monk, but perhaps they thought he was a beggar. Not that Oz is supposed to have those either. Ozma, of course, has done absolutely nothing to guard her Magic Picture or the jug that was once Ruggedo the Gnome King, allowing the monk/spy to walk off with both items with barely an effort. Indeed, he almost gets a free dinner out of it. It will not surprise you by this point to discover that Ozma has no idea how to regain her magical items and the jug, leaving Mandy to save the day.

Mandy is one of Thompson’s most cheerful, practical minded heroines, a bit impetuous, perhaps, but brave, with a decided sense of humor. She does not apologize for her appearance or her extra arms. Indeed, she thinks that the Ozians, with their two arms, are the ones who have a problem. But the people of Oz do not react the same way to her. Nox the Ox initially flees in terror, despite befriending her afterwards; the court of Kerentaria names her a witch, based entirely on appearances. Ruggedo, in no position to judge, calls her “odd.” The Patchwork Girl, not exactly known for a “normal” appearance, calls Mandy a monster. And as she travels through Oz, Handy Mandy finds herself under nearly constant attack.

This is not entirely surprising. After all, the book has to have some plot, and Handy Mandy is hardly the first traveler in Oz to face to various dangers. And, to be fair, she brings many of these attacks upon herself. In Turn Town, she breaks into a shop and eats all of the turnip turnovers without permission, raising the ire of its owner. Right after reading a sign saying, “Be Good to Us, and We’ll Be Good to You,” she throws rocks at prune trees, hitting some Hookers (not that sort of Hookers) who not surprisingly rise up in response, shrieking in self-defense. And so on. But even with this caveat, the hostility shown her is striking. It could be excused, I suppose, as mirroring the reactions she might face in the real world, but this is, after all, Oz, a land and a series that originally and usually embraced those of odd and differing appearances.

The negative reaction extends to her name as well. In her own country, she is merely Mandy, the Goat Girl; in Oz, she becomes Handy. This follows a long Oz tradition of naming people for what they look like (the Patchwork Girl is a girl made out of patchwork, and so on) but in the context of the hostility that greets her, it’s disturbing.

Only three characters ignore Mandy’s appearance, completely accepting her as a person, not a freak. Oddly, one of these is the villain, the evil Wizard Wutz, probably because he’s too focused on his Evil Plans to pay attention to such minor things as arms. The other two are the young king Kerry (shaken by his kidnapping, and grateful for any hope of release) and Glinda the Good. Otherwise, everyone looks first, judges badly, and learns only later.

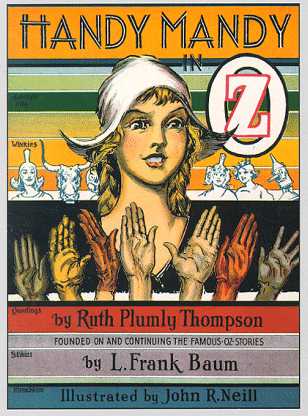

Even the illustrations seem to follow this theme: perhaps to keep suspense, but perhaps also to assure that readers would have a chance of learning to like Mandy before learning about her arms, the interior illustrations initially hide Mandy’s arms, although the arms appear brazenly on the cover. The interior illustrations only show the arms after they are mentioned in the text, and even in later images, John R. Neill, the illustrator, frequently chooses to hide Mandy’s body, and therefore her arms. (Although it’s entirely possible that Neill simply didn’t want to go through the effort of drawing that many hands.)

Despite this, a human girl refusing to apologize for her very different appearance, and even defending its practicality, is a refreshing change from the more typical characterizations of disability and difference in children’s literature. Thompson, to her immense credit, avoids two of the most common disability narratives: the angelic disabled girl who exists to teach everyone moral lessons about the True Meaning and Goodness of Life, or the girl who Must Learn to Overcome Her Disability. Mandy, with her habit of not thinking things through, and a decided bit of a temper, is delightfully flawed, and she does not see any disability that needs to be overcome. Rather, she demands to be accepted for who she is, and assumes she will be. The attitude works. By the end of the book, Handy Mandy is accepted, celebrated and honored, a more than welcome guest in the Emerald City and the rest of Oz, although Thompson notes that Handy Mandy never quite forgives Scraps for that original, monster, reaction.

Meanwhile, I have difficulty forgiving Ozma for still more Ozma fail. Not only does she fail to notice Mandy’s good qualities until Glinda comes to Mandy’s defense, but also places yet another ruler she has never interviewed or even met in charge of one of the little Oz kingdoms, without asking anyone there for comment, and forces the pale people of Silver Mountain, who have spent years never seeing the sun, to live in the bright sunshine again with no thought for their eyesight or their sudden need for sunscreen. (And maybe they like living in the dark. Who knows? Ozma never even bothers to ask.) When told that her magical objects have been stolen by a monk, Ozma reacts by saying that she thought her troubles were over (this is no excuse for not setting up a basic magical security system, Ozma); it takes Betsy Bobbin, of all people, to provide common sense with a pointed suggestion that perhaps just sitting around and waiting to be conquered is not the best of ideas here. Not that this suggestion moves Ozma to, you know, do anything. Once again it falls to the Wizard, the Scarecrow, and Dorothy to provide practical help.

Which is why I find myself in full agreement with Mandy, who, after hearing about Ozma’s rulership of Oz, is “positively aghast” (sing it, sister!). She also points out an immediate flaw with Ozma’s “do not practice magic” law:

…we are not practicing magic, we don’t have to practice it—our magic is perfect, so put that in your pipe and smoke it Miss Ozma to Bozma.

I rather like this girl.

It cannot be denied that the ending of this book, is, to put it kindly, a bit muddled. After reading it a couple of times, I have to confess that I still don’t get what’s going on with the silver hammer. Worse, despite multiple, multiple repetitions of Ozma’s “Do Not Do Magic Unless You Are the Wizard of Oz or Glinda” law, Mandy summons an elf, by magic, who proceeds to chatter about all of the magic he’s been practicing—all right in front of Ozma, who just nods. This is more than mere Ozma fail: the “Do Not Do Magic” is an actual plot point of the book, even if one that’s completely forgotten by the end. Ozma then follows this up by returning various stolen magical items back to their original owners, who will all presumably do magic with them, thus breaking the law, enabled by Ozma. Sigh.

The muddled ending may have been a result of Thompson’s growing exhaustion with the Oz series and disillusionment with the publishers, Reilly and Lee. (Anger and irritation with Reilly and Lee would become a familiar theme for the rest of the canonical series.) Already, she had begun to look for other, more lucrative writing projects. Her disillusionment and exhaustion would have an even more profound effect on the next two books.

Mari Ness must admit that her own magic remains decidedly in the practicing, imperfect stage. (In other words it doesn’t work at all.) She lives in central Florida.