The final act of Siegfried makes up for the relatively light comedy of Act II with three fairly complex conversations: one between the Wanderer and Erda; the second between the Wanderer and Siegfried; the third between Siegfried and Brünnhilde.

The first begins when the Wanderer wakes Erda from her sleep beneath the earth—remember Erda from the end of Das Rheingold, and her warning that events in that opera would lead to the end of the gods. Erda is also the mother of the Valkyries from Die Walküre (and Wotan is their father); note that Wotan’s wife Fricka, who we last saw castigating Wotan for his philandering, is nowhere to be found in this opera.

The Wanderer is deeply troubled, and asks Erda for knowledge of the future. But Erda seems confused and perhaps terrified—she has no counsel for him, and so Wotan decides that he has had enough of the old order of things. The twilight of the gods will be brought about by the twin forces of human love and free will, and Wotan eloquently reconciles himself to this, asserting that this new world will be more glorious than the one before, while still making a last defiant statement against the forces of fate that will inevitably sweep him and his kind aside.

As Erda retreats and returns to her slumber, we shift to Siegfried, who’s being led by the woodbird to Brünnhilde’s rock, where she’s surrounded by a ring of fire. However, the woodbird suddenly abandons Siegfried in a forest (represented here by a group of men and women with long poles attached to them by harnesses) only for Siegfried to find himself in conversation with the Wanderer. The Wanderer, of course, does not identify himself as a god, and Siegfried’s own grandfather.

Having just killed Mime and obtained the Ring, Siegfried is high on himself and answers the Wanderer’s questions about his identity with swaggering insolence. When Siegfried eventually dismisses the Wanderer by commanding him to either stand aside or be cut down by his sword Nothung, the Wanderer raises his spear and prepares to fight. In Die Walküre this spear was strong enough to shatter Nothung, but in Nothung’s new incarnation, re-forged by Siegfried, it cuts through the shaft with a single blow. (Wotan’s spear is notable for the binding contracts engraved on its shaft, so symbolically, this can also be read as free will destroying the laws that bound humanity to the gods, and the gods to each other.) The Wanderer, defeated, stands aside, leaving nothing between Siegfried and Brünnhilde but the ring of fire.

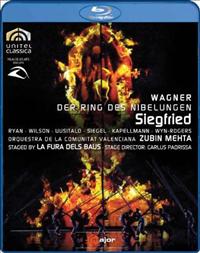

I’ll confess that this is the moment in the opera (and in the cycle) when the music starts to become noticeably difficult for me. Until now I’ve been able to follow the interrelated motives with relative ease, and so the music has sounded both tuneful to me as well as providing commentary on the narrative. But here things get complicated—you have not just Siegfried’s and the Valkyrie themes, but a few others that are related to other characters as well as emotions. (Serious analysis of Wagner’s motives is outside my talents as well as the scope of this post. As I mentioned in the introduction to this series of posts, the best introduction I’ve found to Wagner’s use of leitmotifs is Deryck Cooke’s Introduction to Der Ring des Nibelungen, which is available at a number of places online and in stores. The physical release of this recording comes with a booklet that I’d judge to be necessary for full comprehension.)

Siegfried enters the ring of fire (and here the ring of fire is represented by people in black spandex holding torches, who douse them and flee the stage when Siegfried approaches Brünnhilde). At first Siegfried mistakes Brünnhilde for a man (which, given her costume in this staging, is hardly credible!). But when he removes her armor, he sees that she is a woman, and for the first time he experiences the fear that the dragon could not teach him. (Lance Ryan, the tenor singing Siegfried, pulls this off by letting a tremor creep into his voice, his shoulders slumping as he crosses his arms around himself. For most of the rest of the act he uses his body language to portray Siegfried as insecure and timid, the flip side to Siegfried’s insolence and childlike naïvete.)

He eventually gets up the nerve to kiss her, waking her. Brünnhilde then rapturously greets nature, glad to be awake and alive (with Siegfried viewing her in concealment from the other side of the stage). Once Brünnhilde asks to see the person who woke her and released her from imprisonment, Siegfried reveals himself, and an extended duet (over a half-hour) commences during which they slowly but surely succumb to love, and then passion. (Anna Russell, in her comic commentary on the Ring, bluntly points out: “She’s his aunt, by the way.”)

Though these final moments of the opera are as tinged with nihilism as Wotan’s conversation with Erda—Brünnhilde, having relinquished her status as a demigod to become Siegfried’s loyal wife, seems as eager as Wotan to see the death of the gods brought about—the music here is so joyously rapturous that nothing could possibly go wrong with the romance between Siegfried and Brünnhilde. Right? Right?

Next: Götterdammerüng. Hoo boy.

Dexter Palmer is the author of The Dream of Perpetual Motion, published by St. Martin’s Press.