I first discovered Tove Jansson’s fifth Moomin book, Moominsummer Madness, while rooting through my stepbrother’s bookshelf shortly before my 9th birthday. The story of floating theatres, Midsummer magic, and a sad girl named Misabel who becomes a great actress was a favorite summer read for several years after. But it would take me two decades, a trip out of the closet, and a discovery about the book’s author to fully understand why.

The fact that Jansson was a lesbian is not very well known, thanks perhaps in part to earlier biographic blurbs that identified her as living alone on Klovharu Island. In actuality, she summered there with her partner Tuulikki Pietilä, a graphic artist who collaborated with Jansson on a number of projects, including a book about Klovharu, Anteckningar från en ö (Pictures from an Island), in 1996. Some have even speculated that Jansson based the boisterous, friendly (and quite delightfully dykey) Moomin character Too-ticky on Pietilä.

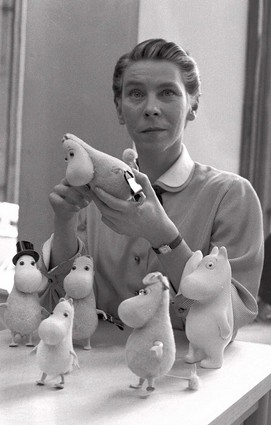

As a prolific artist, sculptor, illustrator and writer, Jansson also lived a bohemian lifestyle similar to the one in which she grew up as the child of two artist parents. Unsurprisingly, Moominvalley is awash in the concerns of such a life, from a reverence for nature to a respect for relaxation and the act of making art.

Likewise, I would argue that Jansson’s Moomin books were shaped by her sexuality. Although there are no openly queer Hemulens, Fillyjonks, Mimbles, or Moomins living in Moominvalley, neither is there a social structure which mandates heterosexual behavior, and in which the roots of queer oppression can always be found. Moomintroll is in love with Snork Maiden and Moominpapa with Moominmama not because it’s the expected thing to do, but because each truly admires his or her beloved. This kind of romantic relationship, free of gender roles and their toxic expectations, is something that queer couples of all orientations and gender identities have long upheld as a good thing for people and for their societies. And Moominvalley reaps bumper crops of these good results. No one hassles characters like Fillyjonk or Gaffsie for being unmarried; Moomintroll doesn’t feel any need to do violent or abusive things to prove his masculinity; and if Snork Maiden likes jewelry or Moominmama enjoys cooking, they do so because these things truly interest them.

Speaking of Fillyjonk, she is also the star of one of my favorite Moomin stories, “The Fillyjonk Who Believed in Disasters” in Tales from Moominvalley. This tale is notable because it emphasizes another theme that queer people will find familiar: The importance of being true to oneself. Timid little Fillyjonk lives in a house she hates among piles of relatives’ belongings, fearing all the while that something will destroy the life she knows. Yet when a violent storm demolishes her house, Fillyjonk finds the courage to embrace an identity free of her family’s literal baggage.

“If I try to make everything the same as before, then I’ll be the same as before myself. I’ll be afraid once more… I can feel that.” … No genuine Fillyjonk had ever left her old inherited belongings adrift… “Mother would have reminded me about duty,” the Fillyjonk mumbled.

In Moominvalley, everyone from Fillyjonk and Too-ticky to taciturn Snufkin and mischievous Little My is not only part of the Moomin family, but Family, in the truest sense of the queer term. I’m forever glad that Jansson’s books played a part in shaping my own identity as a queer child, and I hope that her Moomins will continue to be family to queer people of all ages.