Ryunosuke Akutagawa, best known in the English-speaking world for the short story collection made into the film Rashomon, created dark, fantastical, frightening and funny stories. While the Japanese fascination with tales of the grotesque is nothing new, Akutagawa was among the first, perhaps the best, to take ancient folklore and imbue it with a menace and uncertainty that resonated with a turn-of-the-century Japanese audience and continues to interest readers all over the world.

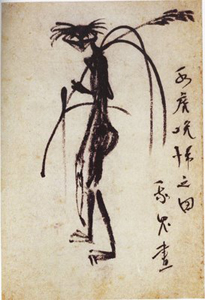

He accomplished this modernization of old fears with great authenticity because he lived a life full of contrasts and anxiety. His working class father ran a dairy. His mother came from an aristocratic family, former retainers of the Tokugawa Shogunate, with generations of artists and samurai. His mother went insane and died young in utter delirium, obsessed with drawing kitsune. After her death, her siblings took young Ryunosuke away from his father and adopted him.

During the Mieji Restoration (the end of the Shogunate and the return of Imperial power), Japan’s on-again, off-again trade relations with Europe resumed and the age of samurai came to an end. (The loss of the samurai ethic during periods of westernization figures into several films by Akira Kurasawa, who adapted Rashomon for the screen, based mostly on the story “In a Grove.”).

By the time Akutagawa was a schoolboy, European fashions, music and authors were very much en vogue in Japan. Akutagawa, however, learned only traditional Japanese arts and literature at home. Early on, he developed a deep love of old folktales such as those found in the Konjaku Monogatari (Tales of the Past), elements of which would be retold in Rashomon. He feared the statues of tanuki in the garden and found the family memorial tablets, lacquered black with gold kanji, terrifying. Most of all, he feared that he would go mad just as his mother had.

As a young man, he developed a fondness for certain western authors (Gogol, Poe and Swift are obvious influences), and when it came to his own stories, he would mix western storytelling styles with old tales of ghosts and monsters (of the human and inhuman varieties), often setting the stories in an unspecified time in the past or a distant land. His reasons are simple and not dissimilar to those of current fantasy authors: “It will be extremely difficult to treat [an] extraordinary incident—simply because it is extraordinary—as happening in contemporary Japan; and if; against my inclination, I do so, then the reader will, in most cases, find it unnatural and, as a result, the theme itself will be destroyed.”

As a young man, he developed a fondness for certain western authors (Gogol, Poe and Swift are obvious influences), and when it came to his own stories, he would mix western storytelling styles with old tales of ghosts and monsters (of the human and inhuman varieties), often setting the stories in an unspecified time in the past or a distant land. His reasons are simple and not dissimilar to those of current fantasy authors: “It will be extremely difficult to treat [an] extraordinary incident—simply because it is extraordinary—as happening in contemporary Japan; and if; against my inclination, I do so, then the reader will, in most cases, find it unnatural and, as a result, the theme itself will be destroyed.”

“In a Grove,” (often compared with Ambrose Bierce’s “The Moonlit Road”) exemplifies the concept of an unreliable narrator. It tells the story of a murder from four contradictory perspectives, including the account of the victim via a psychic medium. The shifting nature of subjectivity among principle characters is a topic he revisits in a number of stories. I can’t help but assume that living in the middle of major cultural shifts, with aristocrats, farmers, artists and lunatics as role models, Akutagawa was right to question the veracity of perspective.

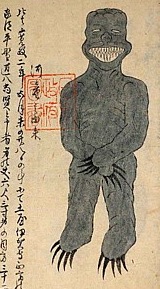

His mother’s manic interest in kitsune is mirrored in Akutagawa’s later fixation with kappa. A kappa is a small impish creature with a body like a turtle, face like a tiger, a beak and a round saucer full of water on its head. Akutagawa’s last major work was the novella Kappa, in which a mental patient relates his time as a captive and observer of Kappanese life in Kappaland. The overt narrative is a Swiftian social satire with occasional hints that the narrator has, in reality, only ever been in a mental institution.

His mother’s manic interest in kitsune is mirrored in Akutagawa’s later fixation with kappa. A kappa is a small impish creature with a body like a turtle, face like a tiger, a beak and a round saucer full of water on its head. Akutagawa’s last major work was the novella Kappa, in which a mental patient relates his time as a captive and observer of Kappanese life in Kappaland. The overt narrative is a Swiftian social satire with occasional hints that the narrator has, in reality, only ever been in a mental institution.

Kappanese society parodies Japanese culture through reversal or extreme, or both. In Kappaland, she-Kappas chase the he-Kappas, mating against the male’s will with such ferocity that he-Kappas end up traumatized and injured. Birth control is considered absurd, but very late-term abortions…voluntary, no less, are common. Just before a baby is due, the Kappa father puts his mouth to the mother’s vagina like a telephone and says loudly, “Is it your desire to be born into this world, or not? Think seriously before you reply.” If the Kappa fetus decides against being born, it says so, and the mother is injected with a fluid that ends the pregnancy with her belly deflating like a balloon.

If a Kappa is told he is to be executed, the knowledge itself will kill him. This is, I think, a joke version of the intense social constraints of Japanese society. The Kappanese religion of Viverism, which makes saints of European philosophers and artists (with the exception of author Kunikida Doppo, a pro-democracy Mieji-era Christian), could be read as a satire of the Japanese fondness for things European beginning with the Mieji Restoration.

If a Kappa is told he is to be executed, the knowledge itself will kill him. This is, I think, a joke version of the intense social constraints of Japanese society. The Kappanese religion of Viverism, which makes saints of European philosophers and artists (with the exception of author Kunikida Doppo, a pro-democracy Mieji-era Christian), could be read as a satire of the Japanese fondness for things European beginning with the Mieji Restoration.

Akutagawa himself said the book has less to do with specific social critique than with an overall disgust with life. In fact, the final chapters of the story can be thought of as an ode to suicide. The mental patient narrator longs to leave the human world for good, and return to Kappaland forever.

Akutagawa committed suicide by poisoning at 35, following a rapid descent into mental illness that in many ways resembled the madness of his mother. I suspect that a lifelong obsession about becoming insane creates a self-fulfilling prophesy.

Akutagawa committed suicide by poisoning at 35, following a rapid descent into mental illness that in many ways resembled the madness of his mother. I suspect that a lifelong obsession about becoming insane creates a self-fulfilling prophesy.