The sun turns black, earth sinks in the sea,

The hot stars down from heaven are whirled;

Fierce grows the steam and the life-feeding flame,

Till fire leaps high about heaven itself.

Now Garm howls loud before Gnipahellir,

The fetters will burst, and the wolf run free;

Much do I know, and more can see

Of the fate of the gods, the mighty in fight.

Now do I see the earth anew

Rise all green from the waves again;

The cataracts fall, and the eagle flies,

And fish he catches beneath the cliffs.

— Voluspo, The Wise-Woman’s Prophecy

All the Windwracked Stars weaves Norse Myth into the warp and weft of a distant post-apocalyptic future, where the death of the gods is recorded history and rune magic is the basis of technology.

One thing that the Eddas, the Norse myth-poems, are famous for is ragna rök—the end of the world, the Norwegian Armageddon. The gods, the giants, the Fenris-wolf and the World Serpent, the valkyrie and all the rest are fated to destroy each other in one final battle—and their mutual destruction paves the way for the birth of a new world.

One thing that the Eddas, the Norse myth-poems, are famous for is ragna rök—the end of the world, the Norwegian Armageddon. The gods, the giants, the Fenris-wolf and the World Serpent, the valkyrie and all the rest are fated to destroy each other in one final battle—and their mutual destruction paves the way for the birth of a new world.

Or does it?

In Elizabeth Bear’s All the Windwracked Stars, Muire is among the last tattered remnants of ragna rök, a valkyrie who’s a poet and blacksmith but not a fighter, who ran in fear from the battleground where her brethren—sisters and brothers both Bright and Tainted, the Wolf that ate the sun and Odin in particular, the intelligent flying steeds called valraven—have slaughtered each other in the freezing snow. She returned to bury the dead, and discovered two things: a valraven named Kasimir, broken but still alive; and that the Wolf has done a runner. Oh, and that the world, and unfortunately her in her shame of cowardice, are still around, even if the heavens are empty of gods and angels.

Lest you think that this is merely a fantasy happening in ye olde times, or yet another extenuation of Norse myth into Our Modern Times, the rest of the story takes place in the far future, when what’s left of humanity barely survives in the war-ravaged city of Eiledon. The heartbeat of civilization is sustained by an aging scholar-sorceress—and Mingan, the human form of the Fenris wolf, seeks to tear out this last heart of Midgard.

Much of Elizabeth Bear’s work, including this one, reminds me of Hayao Miyazaki in his more Princess Mononoke moments: world-building with a rich mythology that draws from traditional legend and lore, almost entirely reshaping them; characters with complicated desires and motivations, where villains occupy grey areas instead of just the shadows (even the worst of wolves); and themes of cycles. Such a combination results in a tale that is complexly layered, and where sussing out the cause-and-effect relationships of motivations and events can be dizzying. The reader is both several good leaps aside from everyday reality, yet still thrust into a non-straightforward play of tangled relationships—and both factors are intimately related.

I’m overly fond of this sort of vertigo-inducing yarn, for, if done well, it’s a rich tapestry of meaning, resonating throughout the story. The problem is that it’s difficult to do well while remaining approachable, and reading is often a matter of full intellectual engagement, rather than skimming happily off plot waves. All the Windwracked Stars is not an exception.

There’s an extra hurdle for All the Windwracked Stars in regards to approachability: its far-future technology is driven by ancient rune-magic. This results in wonderful, haunting visuals. There is an enormous chunk of city ripped up from the ground and suspended in mid-air, with green and vibrant University grounds on top, and a dank and Blade Runner-style underworld below. The transmuted Kasimir is a mechanical creature, complete with articulated wings, yet is still alive and of a magical, iron-hot nature. An intricate clockworks keeps the city alive, in the form of a steampunk moving model universe. The science-magic doesn’t completely gel: the few acts of raw magic occurring in city settings stand out glaringly. They say that any sufficiently advanced technology is magic, but the problem is that any technology here is magic—what to take for granted, what to question, and what to simply marvel at is confused, because there is no basis for comparison.

The main viewpoints are the most interesting: the long, thoughtful history and now-too-human nature of Muire; the memories and thoughts of Kasimir who, after all, is a two-headed flying mythical steed to boot; and the hunger and conflicting desires of Mingan. They tie the past to the present, their eons-long motivations driving their decisions, which drive the plot. The two minor viewpoints are buffeted about for the most part, but present the modern world through the two main types of mortals: Cathoair, a more-or-less human character, and Selene, a cat-human hybrid (number of cat-girl jokes in book: 2). I loved Muire the most—the valkyrie next door, so to speak—her ages-old insecurity plays well off of Kasimir’s equally old, wry assurance. Mingan is captivating in a serial-killer way, shading from Hannibal to Dexter, and we don’t get enough of him. Selene’s way of looking at things is intriguing as a warrior cat, though less so than the immortals. And Cathoair’s viewpoint is the least interesting, not because he’s a boring character (indeed, he’s got a humorous blend of innocence and cynicism) but primarily because he’s human like us, yet doesn’t serve as a identifying character—that would be Muire.

The Voluspo appears to be the part of the Elder Edda from which the novel draws the most inspiration, and its themes of death and fate, destruction and rebirth, vengeance and forever unrequited love are surprisingly realized throughout the plot as twists and counterpoints. The final reprise is itself the ultimate Nordic sentiment: hope in death. These revelations are the the most Miyazaki-like, not just in their inclusion of all sides of the war, but in their fantastic conclusions drawn from the mystic web woven by the story. Once revealed, they feel natural and even forgone, but no less wondrous for that—and you don’t have to know anything of the Eddas.

I enjoyed All the Windwracked Stars, at first mostly from an intellectual standpoint, warming up emotionally only later. It’s thinking reading, with enough satisfaction here and there to keep reading, but most of the satisfaction comes after the end—like eating the sun, it takes a while to digest, and longer still for your system to cool. Personally, I’m compiling a tricked-out Kindle version of the Elder Edda from sacred-texts.com to bide the time.

All the Windwracked Stars is book 1 of The Edda of Burdens. By the Mountain Bound and The Sea Thy Mistress are due in 2009 and 2010. For sample chapters, see Elizabeth Bear’s website.

And Now for the Kindle Bit

All the Windwracked Stars is beautiful on the Kindle while remaining highly readable. It manages to avoid some of the most glaring mistakes that translations to the Kindle sometimes make, and the one “usual” mistake it makes it does so elegantly—mostly because the Kindle can render anti-aliased text.

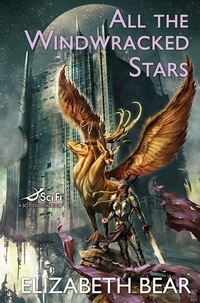

First, I do miss the cover image in this case, even if it would be grayscale. The colors would need some contrast adjustment, but this is the type of cover that would look moderately good on the Kindle after desaturating its color palette. The cover page is a distinctive and storage-light replacement, however.

There is a table of contents, very well done, with the fancy header titles that are still readable:

Good care was taken in re-presenting the chapter pages:

The main body text has a font that’s non-standard, usually a sign of disaster and much Ibuprofen on my part.

However, this case is an exception; the font is highly readable on the Kindle. Often when a font is chosen by a publisher, not relying on the Kindle’s extremely capable Times-style default, it’s one that doesn’t anti-alias well, which makes me want to stab things. Not in this case.

It helps that the font size isn’t set to something slightly smaller than the normal font size, another mistake that publishers make that can badly affect readability.

It’s much prettier on the Kindle itself, since the Kindle’s screenshot mechanism doesn’t capture its wider range of gray tones.

The Kindle apparently supports embedded fonts, which is not a standard with Mobipocket (but does pave the way for the more complex styling in the ePub standard). When I magnify the text, even the fancy bits get larger (not the case with plain images) and flow naturally:

All in all, this is a very good translation to the Kindle. Hats off to whoever did this one.