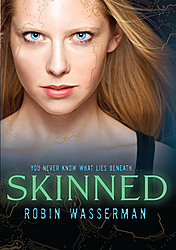

Robin Wasserman is the author of several books, including Hacking Harvard, Chasing Yesterday, Seven Deadly Sins, and her latest, Skinned. If you’re not familiar with her, that could be because her work is shelved in YA and her past books were not particularly SFnal. But Skinned is sure to get her on many a SF fan’s radar.

Skinned tells the story of Lia, a young girl who has it all, until she nearly dies and has her consciousness transferred into a robot body. I interviewed Robin and asked her to tell us a little bit more about the book and what inspired it.

This type of story is kind of the ultimate fish-out-of-water story. What was Lia like before her accident?

At the beginning of the book, Lia is a bit of a stuck-up, selfish alpha girl. She’s a high school senior, a track star, a daddy’s girl (and daddy’s favorite), who believes she deserves everything she’d been given. She doesn’t give much thought to the way her world is structured, and she knows she’ll never have to. When she does think of those less fortunate than her, the logic generally runs as follows—they must not mind being poor, otherwise they’d try a little harder. Suffice it to say, she’s not particularly likeable at the outset. But the download is a rude awakening for her, and it opens her eyes to a lot of realities she would have preferred to ignore. She befriends some people on the fringe that she would never have noticed before, and starts asking questions about the world and about herself. She realizes how selfish she’s been and how now, that selfishness can destroy everyone she cares about. So she’s forced to make the kind of sacrifice the old Lia Kahn would never have considered. But then, as she slowly comes to understand, she’s not the old Lia Kahn. She’s something new.

How does the process work—downloading the human consciousness into the computer mind?

The brain is frozen, cut into thin slices, scanned, and then mapped onto a computer. (As it turns out, there are scientists who speculate about the best ways to do this, so I cobbled together the procedure from their research.) Memories are periodically backed up, so that if necessary, the brain can always be downloaded into a new body. Externally, the body mimics human bodies—it’s anatomically correct and covered in a synthetic flesh that looks and feels nearly real. Internally, of course, there’s no attempt to replicate blood or organs or anything like that. Like the most cutting edge of artificial limbs, Lia’s body is wired for ‘natural’ seeming movement. It registers sensations—though not smell or taste—and her brain processes them as such, although nothing feels like an exact match to her experiences in an organic body. As Lia puts it, with her hand on ice, she knows that it’s cold. She registers the temperature. She just doesn’t feel it. Only extreme sensations—extreme pain, for example —overcome her conscious awareness of this artificiality.

That’s a cool enough concept to power a book, but you didn’t stop there—you’ve got lots of other nice touches to make your future feel fully-realized.

This is also a world with a lot of prenatal genetic manipulation, medical treatment tailored to DNA, refrigerators that know what your body needs to consume, toilets with med-chips that analyze your waste, cheap and easy lift-tucks that give you a new, youthful face whenever you need a touch-up, cars that drive themselves. Wearable technology (shirts that flicker with streaming video from the net, solar-powered bikinis) is a must, and your biometrics inform your music player what you’re in the mood to hear. There are no more personal computers, only ViMs—Virtual Machines—screens that provide you an interface to the network. All data rests on a few massive, secure servers. (Think Google desktop, writ large.) Everyone does everything through their own personal social networking site, called a zone, where images, information, communication, everything is stored from birth through death. It’s a second life, in many ways more real than the first.

This is your first foray into SF, isn’t it? What sort of challenges did you face, writing a book in a genre you hadn‘t written in before?

This is my first real science fiction novel, and I was pretty intimidated by that at first. I’d decided to set it in the near future, without stopping to think what kind of challenge that would pose. When you set a book in the distant future, you can create whatever kind of world you like—but since this book is set within the twenty-first century, I felt bound to construct something that would seem somewhat realistic. I wanted this world to feel like a natural outgrowth of our own. (That is, if all the problems we have bubbling under the surface suddenly exploded.) So I spent a lot of time reading futurists’ predictions, trying to wrap my head around social trends, technological innovations, experts’ best guesses as to where we’re heading. In the end, this world-building research was the most demanding—but also the most satisfying—part of the work. I’d already done most of the automata research in grad school, and had a pretty good idea of what I wanted to say about the connection between man and machine (there was still more reading to be done, but I knew where to find it). On the world-building, I was flying blind. Everything else I’ve ever written is set in a realistic present, and I was terrified that I would create something paper-thin or completely untenable. As a reader, I find that inconsistencies in the world-building can often ruin a book (and that, alternately, the thing I love most about my favorite sci-fi novels is almost always the world, rather than the plot)—so I really dreaded getting it wrong.

What other kind of research did you have to do for the book?

I think I’ve covered this mostly – along with all the futurism stuff, I read a lot about automata and machine culture over the ages (from the enlightenment automata craze, through the industrial revolution concerns of mechanized workers, through the twentieth century horrors of machine wars twinned with the wonders of computing technology). I also had to dip into some research on how the brain functions—with a specific emphasis on how the brain processes emotions and constructs an understanding of self—which meant Antonio Damasio’s work on cognition was particularly helpful. The most unexpected source of useful information was the reading I did on victims of spinal cord injury. At the beginning of the book, Lia spends some time learning how to function in her new body, so I wanted to make sure I nailed down the details of rehabilitation—but the more I read about spinal injuries, the more I realized there were a lot of relevant overlaps. This research gave me an insight that really powers the book, which is that much of what we think of as happening in our head really happens in our bodies. (When you’re scared, your muscles clench; when you’re nervous, you get butterflies in your stomach, etc.) I read about a lot of cases in which people with paralysis had a tough time accommodating to the lack of these sensations, feeling like it put the world—and their feelings—at a remove. And I realized that Lia would be grappling with the same issue. So much of the book emerges from that single understanding. How does your mind compensate if your body can’t feel (or in her case, can’t feel in the same way)?

Most authors say all their stories are personal. If that’s true for you, in what way was this story personal to you?

Speaking as someone who was the opposite of popular in high school, I certainly can’t empathize with Lia’s fall from grace, but I suppose I did connect with her post-download feelings of alienation and loneliness. For me, the teen years were all about searching for a place for myself, wondering why I seemed so different than everyone else, wondering especially why no one could look past the surface and figure out who I really was underneath.

A lot of people have picked up on the physical parallels here to adolescence and your body betraying you—and while they’re certainly there, for me this story is much more about what’s going on inside Lia’s head. She doesn’t understand who she is—and she really doesn’t understand how all this can be happening to her, how her whole world could have changed overnight, and is never, ever changing back. It was a painful shock for me when I had that first realization, that ‘bad things don’t just happen to other people’ moment. So I really connected with the part of the character that struggled to accept what was happening. There’s a moment toward the beginning where she’s hoping that she’s in a dream, waiting to wake up—this book is about her realizing she’s never going to.

What’s up next for you?

This is a trilogy, so right now I’m working on the sequel to Skinned, which takes us a lot deeper into the world of the mechs, and explores the consequences of this community getting larger and stronger and demanding its rights from a hostile world. In the first book, the mechs are a mostly existential threat for the orgs (as the mechs call ‘normal’ humans), and vice versa. But in the sequel, the threat becomes real.

In terms of Lia’s character, if the first book is all about her trying desperately to hold onto her humanity, I suppose you could say the second book is about her trying desperately to lock her humanity safely away, and become a machine.