Put on your thinking caps, kids, because I’m about to get academic on your asses.

(Speaking of which, I would love to have an actual, honest-to-goodness thinking cap. Is that something you can buy on Etsy? What does one even look like?)

The vast majority of panels here at Comic Con seem to be glorified press junkets, content-lite presentations that culminate in “sneak peeks” of something you’ll be able to watch on YouTube the next morning (a thrill you’re expected to wait in line an hour or more for the privilege of enjoying). When I saw a panel on the schedule promising an in-depth discussion of comic books that wouldn’t actually be promoting something, well, I was thrilled.

The tiny room was at best a quarter full, natch. (A sneak peek of the new season of Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles was taking place at the same time.) But plenty of insightful things were said, and I can still put Terminator episodes on my Netflix queue when they become available, so it’s a win-win.

Dana Anderson, of the Maine Maritime Academy, compared the X-Men to Romantic heroes in literature. According to Anderson, what distinguishes the protagonists in the works of Shelley (both), Byron, et al from their predecessors is the fact that “they are self-aware”: They know they are unique.

On the one hand, they have special talents, genius and creative inspiration. On the other, they are scorned and feared by the Industrial masses. They endure a “deep aloneness.” (In other words, they are proto-geeks.)

(Read more below the fold.)

Similarly, the X-Men are “inspired,” but their “inspiration lies in their genes, which flower forth with powers.” For the Romantics, poets and geniuses were the unappreciated freaks. For Marvel, it’s superpowered mutants.

Throughout comic book literature, you see the same Jungian archetypes and Campbellian patterns repeated again and again. The success of a superhero character in terms of actual market success is often directly commensurate with how well that hero fulfills the role of one or more archetypes, how well it scratches our collective unconscious itch.

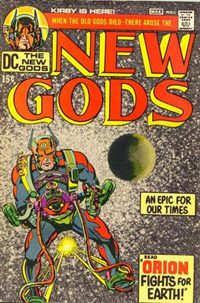

Charles Hatfield, of CSU Northridge, gave a fascinating presentation on Jack Kirby and the “technological sublime”—and whatever that means, you have to admit it sounds pretty cool.

Hatfield actually spent much of his talk defining how he intended to use the term: the technological sublime is “ineffable, awful in the original sense of the word.” It’s the monolith in 2001: A Space Odyssey, disorienting, strange, and terrible. (Kirby actually did a comic book adaptation in the mid-70s that looks even trippier than the film.)

Hatfield also showed us some amazing panels from Kirby’s comics, including one of a planet-sized Promethean creature eternally chained to an asteroid while an ant-sized person looks on from the very corner of the frame. And another of Johnny Storm, having traveled the galaxy for a special weapon to defeat Galactus, tripping out now that he’s realized his own insignificance on the galactic scale. “We’re ants…just ants.”

Kirby wasn’t a scientist or a scientific thinker. His grasp of technology was so loose that Hatfield remembers finding factual errors in his comics even as a child. In fact, Kirby often mixed high technology with ancient mysteries. Doctor Doom was identified as a “scientist and a sorceror.” Kirby was evoking the technological sublime by creating a universe that was “awe-inspiring, existentially dizzying,” one that, next to which, even these superheroic demigods were ants.

Immanuel Kant defined the sublime as that which “does violence to our imagination.” Can you imagine higher praise of a comic book than that?

Seth Blazer of the University of Florida discussed how 9/11 gave birth to the deluge of comic book superhero films in the last seven years. Apparently nebulous threats make us crave a unified hero to rally behind, and a black-and-white conflict of good vs. evil. Sounds right to me.

An interesting question about what defines a superhero—if a werewolf fought crime, would that qualify?—was rudely quashed by a moderator who, after tossing out a quick definition of his own, declared the subject his personal area of academic expertise and thus ineligible for discussion at a panel that didn’t revolve around him. (Sorry, but even the academic comic-book guys sometimes fit the stereotype.)

So I put the question to you: If a werewolf decides to fight crime, would he or she be a superhero? If not, what would it take to make that werewolf qualify? A cape? A secret identity?

(Image courtesy of Wikipedia.)