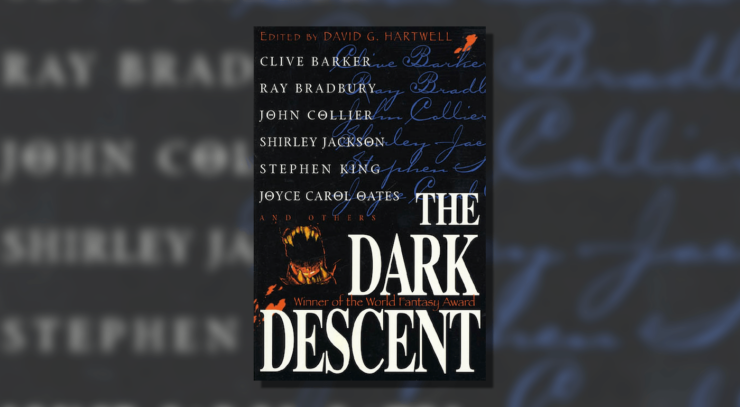

Welcome back to Dissecting The Dark Descent, where we lovingly delve into the guts of David Hartwell’s seminal 1987 anthology story by story, and in the process, explore the underpinnings of a genre we all love. For a more in-depth introduction, here’s the intro post.

If there’s anyone who knew the modern world of monsters, it was Robert Bloch, and “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” exemplifies that mastery. A member of the “Lovecraft Circle,” a group of writers centered around HP Lovecraft whose occult horror works borrowed from and influenced each other, he’s probably most remembered for Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 adaptation of his novel Psycho, which borrowed from true crime, noir, and horror stories to create an iconic modern gothic masterpiece. “Yours Truly” is an earlier story of Bloch’s, but much in the same vein, with its cynical view of a post-World War II America where Jack the Ripper hides in plain sight among citizens who find the idea of a killer in their midst more of a novelty than a source of panic. Through the eyes of Bloch’s disdainful narrator, a horrifying portrait emerges, one where the horror and violence happens not because the average person can’t stop it, but because they’re privileged enough that they don’t have to care.

John Carmody is a psychiatrist approached by one Sir Guy Hollis to help him with a very unusual mission: Capturing Jack the Ripper. As it’s Chicago in 1945, Carmody has no reason to believe Sir Guy’s story, and assumes the man was sent to him because he’s tracking a serial murderer from 1888 and needs immediate psychiatric help. Sir Guy does nothing to win him over, insisting that the Ripper’s spent the decades since his disappearance traveling the world and making blood sacrifices to keep himself young, based on the cycles of the moon. Amused as much as concerned by his British visitor, Carmody agrees to help him, accompanying him to a party attended by artists and other libertines of high society that Sir Guy has identified as his prime suspects. As the two men journey through the high-rises of the hoi polloi and the dive bars of the South Side, it becomes clear Sir Guy refuses to give up his quest, with Carmody only hanging on as minder to ensure Sir Guy doesn’t harm someone. But as an unusual chill and a strange fog creep over Chicago, the question arises: What if Sir Guy is right?

[Note: the following discussion includes some necessary spoilers, so if you haven’t read the story, you may want to catch up before reading on…]

Bloch crafts an interesting conceit—a Victorian-style detective replete with mustache and monocle hot on the trail of Jack the Ripper in 20th-century Chicago, narrated with disdain and amusement by the modern-day psychiatrist forced to play the Watson role to Sir Guy’s Holmes. Carmody’s modern cynicism and barely concealed dislike of everyone around him creates an odd lens for the pair—the modern man who cares very little and is only going along out of novelty, and the older British gentleman who, while sharp, is very much a fish out of water. Carmody evinces the same air of condescension whether describing his supposed friends and confidantes or an unfamiliar dive bar in a Black neighborhood. He snidely comments on the piano at a party being drowned out by a craps game being played in the corner and describes fights and public sex acts all with the same droll tone. This tone places Carmody above everyone else, a disdainful observer of others who passes judgment. He refers to Sir Guy’s initial culture shock as “zoological observation,” and sets himself apart from his artist friends whenever he has the chance. His detachment carries a mild hint of misanthropy and disapproval throughout, brushing off a former lover at the party and watching with only mild interest as his friends turn Sir Guy into a comical distraction.

Sir Guy, meanwhile, believes that his just cause and single-minded focus will win the day over the Ripper, a conviction treated by both Carmody and the other characters with a sense of vicious novelty. His pursuit of justice and strict moral stance seem equally outdated. Upon entering the party where the story’s central action takes place, Carmody and Sir Guy are treated as curiosities. Carmody only goes along for the amusement of watching Sir Guy get a dose of culture shock when exposed to the libertine attitudes of Chicago in 1945. Most of the characters humor Sir Guy and treat him as a passing curiosity, while Sir Guy by comparison treats his quest with stone-faced seriousness as he brandishes a loaded revolver. This is especially clear when the party’s host turns Sir Guy’s revelation that one of them is Jack the Ripper into a parlor game, complete with theatrical narration and a turning out of the lights—a game Sir Guy ends by playing dead and then trying to laugh off the awkward situation. The further the story goes on and the more mockery he endures, the more pathetic he seems, as he claims he’ll turn the Ripper over to the FBI and insists they’ll believe him (in a way that not a single person has, throughout the story). In a final nasty twist of the knife, Sir Guy is done in by the very person he thought was helping him, who (as we know through his own narration) was only humoring the older man to begin with.

This makes that final twist (which unfortunately we must spoil here)—that Carmody is in fact Jack the Ripper—even more unnerving. Hartwell claims in his introduction to “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper” that it “occupies the same moral universe as ‘The Whimper of Whipped Dogs’,” but Ellison’s snarling outrage imagines an oppressive outer force, a dark god tormenting the denizens of the city. Bloch, consistent with his noirish handling of “Yours Truly,” is more nihilistic. In “Yours Truly,” a misanthropic serial murderer hides in high society and covers up his crimes in a way that everyone merely ignores. Privilege shields most people from Carmody’s monstrous tendencies—not that they’d believe him even if he came right out and admitted his identity and various crimes. Carmody, despite his racism, misanthropy, and judgmental air, thrives because he can hide in plain sight among the apathetic and terminally bored members of his social circle. It works so well that not even Sir Guy catches on, expecting the Ripper to stand out from the crowd right up until the moment Carmody shanks him in the kidney.

That nihilism and detached sense of amusement, the idea that justice will not prevail in a world where misanthropes like Carmody can survive and thrive, is the true horror of “Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper.” Even without Sir Guy’s exaggerated and quixotic crusade against Jack the Ripper, Carmody (especially upon rereading, where it’s obvious he’s leading Sir Guy on) is still a monster who barely disguises his racism, general dislike of and disdain for other humans, and perfectly comfort with committing atrocity. He thrives not because no one’s able to stop him, but because (much like in the actual Ripper murders) most people view such things as little more than a lurid tale that’s happening to victims—others—who are seen as eminently disposable…assuming people even care at all. There doesn’t need to be some god of violence or external force: Apathy, bemused detachment, and the simple knowledge that violence will never reach your doorstep do the job all the same.

If anyone does decide to care, well, Jack’s waiting out there in the fog.

And now over to you: What was your first experience with the work of Robert Bloch? (Mine was the movie version of Psycho, watched in a run-down motel, scarily enough) And also, what’s your favorite Jack the Ripper story?

Please join us in two weeks for “If Damon Comes” by Charles L. Grant.