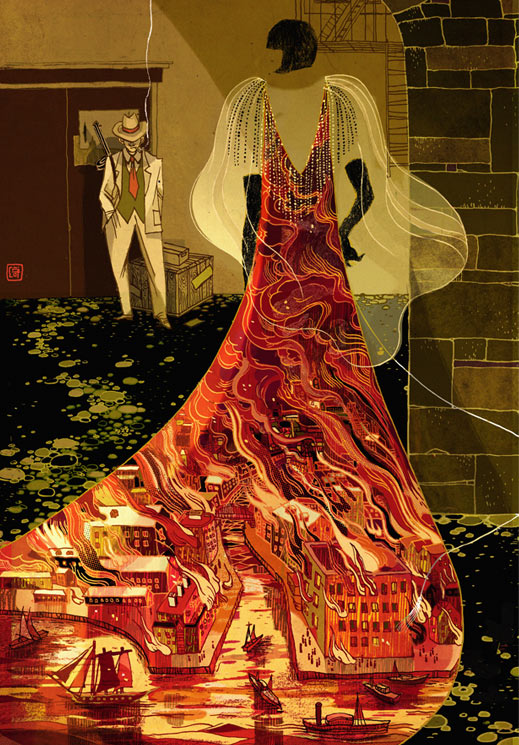

Few know that the Great Chicago Fire was started deliberately, bringing genocide to deadly creatures called Shades. Fewer still know that they didn’t die, not quite…and one human will confront the truth when an ominous beauty makes him gamble for his life.

Read “Jacks and Queens at the Green Mill,” which is set in the world of Rutkoski’s newest novel The Shadow Society.

This story was edited and acquired for Tor.com by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux editor Janine O’Malley.

Pathetic.

Zephyr cast a glance over the Green Mill Lounge’s sunken garden, at the sweat-dazzled ladies in their thin dresses leaning on men who called for more buckets of champagne. The Chicago night was fuzzy with heat.

Not that Zephyr felt it. That would require skin. It was a good thing she didn’t have any at the moment. If she had, she would have been sweltering along with the humans. If she had a face, her expression would have shown what she thought of them.

Their parents or grandparents had burned Chicago down in 1874. Now, five decades later, their reborn city was an ugly thing, with straight streets and right angles, full of humans who drank and laughed and had no idea that they were living their lives in a space hollowed out by the murder of a people better than them in every way, in every thought and intention.

Namely, creatures like herself.

Zephyr floated, invisible, into an alleyway snaking out of the club’s side entrance. She was nothing, a wisp of air.

Then her body molded into being and she became a girl.

Zephyr felt the weight of her flesh settle on the branch-and-twig network of bones. Her short black hair, cropped in this world’s style, swished against her bare neck. She ran fingers over the flat chest of her dress, its tiny black beads sprayed like caviar across the square neckline and dripping in fringes from her shoulders. Zephyr had dressed carefully for this mission. The humans would take her for one of their own. When she walked into the club, no one would give her a second glance.

“Hell-lo,” said a voice.

Or perhaps someone would.

A boy blocked the club’s side entrance. He looked about her age, no more than twenty years old. His body was long, rangy, his stance somehow naturally dishonest, alive with the energy of someone who couldn’t be trusted, but also couldn’t be blamed for it, because it was easy to guess from the way he constantly shifted his weight that he couldn’t quite trust himself either.

But it was his face that stopped Zephyr cold.

Only for a moment. Then she came closer. She walked straight up to him.

Once, Zephyr’s mother had tried to explain to her how an alternate world happened. She had described the sensation: a shiver along the skin of reality, then a jolt, a loss of balance. Every Shade had felt it. On October 8, 1874, the Shades of Chicago looked around at their whole city, at the sheer autumn sky, and didn’t see anything wrong. Everything seemed the same. But they felt half of themselves die. Some part of them blazed up in pain and blew away in ash. They didn’t understand, then, what had happened. They didn’t know that, in this world, their old world, the one where Zephyr faced the boy, humans had led a massacre of the Shades. They had burned Shades at stakes lit throughout the city.

In this world, which they called the Alter, Zephyr’s mother had died along with every other Shade.

In their new world, the one into which Zephyr had been born, her mother was alive.

But it felt, her mother said, as if she lived with the ghost of her dead self. As if she were her own haunting.

Zephyr stared at the boy staring at her, and thought that maybe he understood how her mother felt.

He was hideous.

Half of his face was a twist of scar tissue. One eye was almost hooded by a patch of skin, and his mouth dragged up to the left in a permanent sneer.

He whistled. It must have been hard work, whistling with that mouth. But the sound pierced low and true. “You look like Louise Brooks,” he said.

She frowned.

“The movie star,” he clarified.

She knew what movies were. Her Chicago didn’t have them, but the Alter did. They were all the rage here, mirages of light and dark, faces flitting across the screen like shadows cast by bird wings. Zephyr had even watched one. She had not been impressed.

And the truth was, she found the boy’s assessment a bit insulting. She wasn’t trying to look like a movie star. She had researched the persona she was trying to achieve. It was 1926, and she knew what stylish girls here were supposed to be. “I’m a flipper,” she informed him.

The other half of his mouth lifted. “Do you mean flapper?”

This word made no more sense than the other one. It only served to annoy her.

He kept smiling his warped smile.

But what he called her didn’t matter. His disfigurement didn’t matter. It had made her forget her goal, but would do so no longer.

She moved to brush past him.

He slid a flat-palmed hand into her path. She stopped, drew back. The thought of a human touching her made Zephyr’s skin crawl.

“Sorry,” he said. “The boss is inside. When he’s in the Green Mill, no one goes out, no one goes in.”

It was only then that Zephyr noticed the gun slung from his shoulder. This kind of gun had a name as well as a reputation: the Chicago Typewriter, some people in the Alter called it, or the Chicago Style. A machine gun, one that could kill scores of humans in one sweep. It was what Zephyr wanted, and she couldn’t believe she hadn’t seen before that he carried it, even if the barrel was black, even if his clothes were dark, even if the alley was darker.

It was that face. His face had startled her, kept her from seeing more important things. Like the way his hands weren’t on the gun. It hung loose from its shoulder strap.

“You’re a rather poor guard, aren’t you?” She nodded at the dangling gun.

His hands snapped to it, gripped the stock. “I got distracted.”

“By my movie star beauty?” She gave him a snide smile full of teeth.

“I saw you,” he muttered, chin down but eyes up, never leaving hers. “I saw you appear.”

Foolish, stupid. Why had Zephyr been so cursory, why had she assumed the alleyway was empty before she had stepped into her body? And now . . .

“I know what you are,” he said.

“A ghost.” The word came out flat. A ghost was what people in the Alter always believed they’d witnessed when they happened to see a Shade flicker in or out of sight.

He shook his head. “A Shadow.”

Close enough. Too close.

“My grandda told me about your kind,” he said.

“Oh?” Her voice rode high. This was why Zephyr didn’t like living in her body. She wasn’t used to it. It appalled her, the way the flesh could betray feelings better left unveiled, such as tension. “Then you must know that a bullet won’t touch me, and that you can’t stop me from going through that door.” She could disappear, drift right through it.

He shrugged. “I know there’s a reason you haven’t already.”

Zephyr’s eyes narrowed. Her former plan winked out like a faraway star. A new one began to gleam. Suddenly, her idea of waltzing into the Alter’s most dangerous nightclub and walking out with a machine gun seemed less fun and dramatic, more tiresome. Only small things in contact with her body would vanish with her. She’d have to stay solid to leave the club with a gun.

The boy with the wrecked face presented an easier option—one that was enjoyable, too, in its way.

“Give me the gun,” she said.

He laughed.

“Do it,” she said, “or I’ll vanish, float the ghost of my fist into your chest, and come alive inside your body. I’ll burst your heart into pulp.”

He continued to smile. “You’re not as scary as my boss. I’m one of his bodyguards. If he comes out and sees I’m missing my gun, I’ll wish you’d killed me.”

Her body went still. The stillness had a waiting quality, and when Zephyr realized that, she understood that she was hesitating.

He noticed. And she noticed that he wasn’t really afraid of her, which meant either that his grandfather hadn’t informed him fully about Shades or that this boy was made of stern-enough stuff.

And maybe—she thought, staring at his rippled features again—he had to be.

“You’re fair,” he said quietly.

“Fair?” She wasn’t sure what he was driving at.

“Did you know that, long ago, ‘fair’ meant both ‘beautiful’ and ‘just’? Isn’t that nice, the thought that justice and beauty were once twins?”

“You’re an odd sort of gangster, to be concerned with justice and words.”

“You’re an odd sort of anything. But, I hope, you’re also fair.” A hand pulled a deck of cards from his suit pocket. “Play me for the gun.”

The corner of Zephyr’s mouth twitched. How strange it was, to have flesh, and for it to explain her emotions to her.

Amused. She was amused. “What game?”

“My favorite. Black Jack. Know it?”

As if they didn’t play cards in her world!

Though she wasn’t quite sure if he knew about her world, even if he knew about Shades—unusual enough. The memory of them was supposed to have been obliterated in the Alter after the Great Chicago Fire, which is what humans called the genocide of her people.

“Whoever gets closest to twenty-one wins,” Zephyr said sharply. His expression nettled her. It was patient, ready for anything she might say. That made her impatient, and ready for nothing. “Face cards are worth ten. Aces are one or eleven, player’s choice. Twos are worth two, threes are worth three . . .”

“And don’t go over twenty-one, girl, or you’ll lose.”

Her body decided before her mind did. Zephyr took the cards. After the barest of pauses, during which she wondered what she was doing, and how the evening had taken the shape of this alleyway, this boy, these red-backed cards, Zephyr began inspecting them for folded edges, pinpricks, the signs of a marked deck.

“It’s clean,” he said.

She snorted, and kept shuffling.

“What does it feel like?” he said abruptly. “To go from nothing at all to that?” He waved a hand at her entire body.

It sounded less like a question and more like flirtation. It sounded like he needed to be reminded of some basic boundaries, such as the kind between predator and prey. “And how did it feel, to go from what you were to that?” She pointed at his face.

He blinked. That small movement sent a dart of feeling into Zephyr. It took a moment for her to recognize it as guilt. She folded her arms defensively, and a card from the deck in one hand fell to the pavement. “Well,” she said, “I’m sure a criminal can do a million things to deserve whatever happened to you.”

He bent to retrieve the card. “I’m not sure,” he said slowly, straightening, brushing the dirt from the two of diamonds. “I’m not sure what a ten-year-old kid can do to deserve getting his face held flat against a hot stove.”

Zephyr took the card from him. She slipped it back into the pack, and was silent. Then she said, “When I step into my body, it feels like water before it hardens into ice. Like silk before it’s stretched and stitched onto a wire frame and called a lampshade.”

“Silk and ice,” he said, running the words together so that they sounded like silken ice. “That’s you, all right.”

She packed the deck tight and hard into his outstretched hand. “Deal, guttersnipe.”

He cut the deck, arced the cards between his fingers. “Joe,” he said. “My name’s Joe.” He tossed a three of clubs face up at her sharp-toed shoes.

“Again,” she said.

Another card: the six of hearts.

“Again.”

His hands didn’t move. “The polite thing,” he said, “would be to tell me your name.”

“Again,” she snarled.

He shifted his weight, lifted his shoulder in what was not quite a shrug, just a restless movement. “What’s the harm?”

Zephyr saw, then, that he had guessed her decision that whatever the outcome of the game, he wouldn’t be alive much longer—one way or another. “Fine,” she said. “I’m Zephyr.”

“Ah, the west wind. The gentle one.”

“It’s just a name. A family name. Everyone in my family is named after a wind, or a creature of the air. My cousins have the names of stars. Some families like forest names.” She assured herself that she was telling him this to encourage the suspicion of his doom, because why would she tell him anything about her life, unless she knew his wouldn’t last much longer?

Why would she say anything?

He dealt another card. The jack of spades. “That makes nineteen for you.”

“I can count.”

“Will you stay?”

She glanced at him.

“Will you hold?” he said. “Or d’you want another card?”

Her heart beat. Zephyr was surprisingly nervous about the conclusion of a game whose outcome she had already decided didn’t matter. That heartbeat ratcheted into recklessness. “Another.”

An ace.

The breath came out of him slowly. “That makes twenty.”

“I’ll stay.”

“Yeah,” he said. “I bet you will.”

He dealt himself a king. He paused, lifted one bent wrist to rub it against the buckled scars of his cheek. “Thought there weren’t any of your kind left.”

“Humans think they know everything. Don’t stall. Deal.”

He looked at her. “Why do you want a gun?”

She wasn’t going to answer that. She wasn’t going to explain that while guns existed in her world, they were simple. Not automatic. Guns were useless against creatures that could become incorporeal, and humans didn’t war much with one another when they had a common enemy in the Shades. Zephyr wasn’t going to tell this boy that she would bring his gun back to her Society, for the Council to inspect and decide whether to use.

Zephyr felt tired, and suddenly disheartened.

Joe dealt the two of diamonds that had earlier fallen to the ground. “Gotta keep going, I guess.” He flipped a four, but that made only sixteen.

When the next card came, it seemed as if they’d both been expecting it: the queen of spades. He had gone over, way over, and Zephyr’s legs went watery, like they might melt, and it was relief that she felt, relief that he had lost, because it meant she didn’t have to kill him herself.

He faced her squarely. “I don’t understand.”

It took her a moment to realize that he wasn’t talking about the game.

“I don’t understand why you had to come here, to this club, on this night, to get a gun. There are thousands of guns in this city.”

Zephyr looked at the black paint of the closed club door. She sighed. “The music.”

“You can hear music anywhere.”

“No, you can’t. Not jazz. Not where I come from.”

Confusion made his face uglier. So did a trace of fear, finally, now that the game was done. For some reason, Zephyr didn’t like to see that.

“It doesn’t exist,” she said. “Jazz was never invented. And here . . . the Green Mill has the best jazz. Your employer demands the best.”

Joe’s expression seemed to crumple.

Zephyr held out her hand. “Give me the gun.”

He stepped back. She thought he was going to try to run away. She braced herself for what she would do to stop him. And she would do it, she would. He was only human, and with the life he led he’d die soon enough anyway.

But he didn’t run. He opened the club door.

Music floated out. It infused the night, rich as brassy ozone, light as pattering rain. An upright bass plucked throbbing notes, a drummer brushed the cymbal, cartwheeled a stick across his set. Zephyr heard the trumpeter mute his horn, and it all flowed out into the alley, a music made of the unexpected. A loose-limbered sound, one that made a philosophy of choices, highlighting the fact of them by pretending they didn’t exist, by tripping lightly from one rhythm to the next, from key to key, as if nothing was certain, improvisation was everything, and practice was for fools.

Zephyr knew better. She knew that the musicians practiced for their master. But this was their art: to make their work seem like a game.

A game in which everything could change.

Zephyr looked at her hand, reaching for the gun.

She didn’t want her hand anymore.

She didn’t want her arm. Or her chopped hair. She didn’t want her eyes and the way they widened to see fresh fear on Joe’s face as he unslung the gun. The stories his grandfather had told him must have been accurate indeed.

Zephyr watched the gun swing on its strap as if to the music. If left in Joe’s hands, this weapon could kill humans, who knew how many.

Zephyr told herself that this was why she said what she did.

“Keep it,” she told Joe.

Then she did what she was good at.

She vanished.

![]()

“Jacks and Queens at the Green Mill” copyright © 2012 by Marie Rutkoski

Art copyright © 2012 by Victo Ngai