The tiniest Stephen King book, both in page count and substance, The Colorado Kid came along after King disgorged three of his massive Dark Tower novels. Arriving in early 2005, three years after his last non-series novel, From a Buick 8, it could easily be considered a coda to Buick. Clocking in at a slim 184 pages, set in two locations (a restaurant and a newspaper office), and with only three characters, this is as skinny as King gets.

At this point in his career, King’s line-by-line writing is so polished that he can pull off pretty much anything, from a big fat fantasy series to DVR set-up instructions, with panache. But his one-a-year publishing habit was firmly established by 2005 when this book came out and that’s got pros and cons. As he said around the time of Buick, “I can’t imagine retiring from writing. What I can imagine doing is retiring from publishing…If I wrote something that I thought was worth publishing I would publish it. But in terms of publishing stuff on a yearly basis the way I have been, I think those days are pretty much over…From a Buick 8…so far as I know [is] the last Stephen King novel, per se, in terms of it just being a novel-novel.”

With Colorado Kid he proved himself wrong.

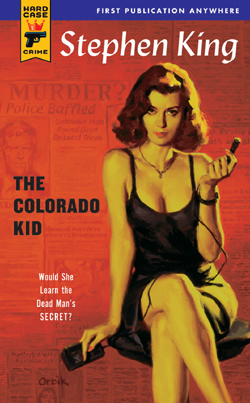

Kid started as a blurb request. Charles Ardai founded his Hard Case Crime imprint to reprint lost hardboiled novels and contemporary books that fit that mold. When he launched his line he wanted to get a blurb from King because why wouldn’t anyone, so he approached King through his accountant, hoping that coming from an unexpected direction might yield results. Five months later, King’s literary agent called and told him that King wouldn’t be providing him with a blurb, he’d be writing him a novel. Ardai, as any publisher would, immediately went out and drank five billion bottles of champagne. He commissioned a beautiful cover painting from Glen Orbik and, as expected, King’s Kid became the line’s best-selling novel and gave the imprint a huge publicity injection. Especially after it later became the basis for the Syfy series, Haven, which ran for five seasons.

The story is set on Moose-Lookit Island, a fictitious nugget of land off the coast Maine, like the location of Dolores Claiborne, or the island in “The Reach” from Skeleton Crew, or “Home Delivery” from Nightmares and Dreamscapes. The first chapter starts in a restaurant with newspapermen Vince Teague and Dave Bowie shocking their intern, Stephanie McCann, by stealing the cash a Boston Globe writer left behind for the bill before bouncing back to the mainland. Teague is 90, the founder of The Weekly Islander, and Bowie is either an androgynous, multi-faceted pop star or the 65-year-old managing editor of that same paper. They’re the kind of King characters who say things like “ayuh” and “Oh gorry.” Turns out the cash-swiping is a test for Stephanie’s powers of deduction, and the two old timers lead her down a path that ends with the realization that they’re playing a shell game with the cash so they can give even more of it to the waitress, tax free.

The story is set on Moose-Lookit Island, a fictitious nugget of land off the coast Maine, like the location of Dolores Claiborne, or the island in “The Reach” from Skeleton Crew, or “Home Delivery” from Nightmares and Dreamscapes. The first chapter starts in a restaurant with newspapermen Vince Teague and Dave Bowie shocking their intern, Stephanie McCann, by stealing the cash a Boston Globe writer left behind for the bill before bouncing back to the mainland. Teague is 90, the founder of The Weekly Islander, and Bowie is either an androgynous, multi-faceted pop star or the 65-year-old managing editor of that same paper. They’re the kind of King characters who say things like “ayuh” and “Oh gorry.” Turns out the cash-swiping is a test for Stephanie’s powers of deduction, and the two old timers lead her down a path that ends with the realization that they’re playing a shell game with the cash so they can give even more of it to the waitress, tax free.

After that, they go back to the offices of The Weekly Islander and talk. That’s it. I’m serious. There is no more. Like My Dinner with Andre, the entire meat of this story is one conversation. That’s probably going to be a jumping off point for a lot of people, and that’s okay. While his book-a-year habit means that some years he’s going to spread his jam thick, some years he’s going to spread it pretty damn thin, like Kid, which feels like little more than a sketch on the back of a napkin. But that’s okay, because King’s one-a-year habit reassures us that if you don’t like this book, another one will be coming along soon enough.

What brought the writer for the Boston Globe to Moose-Lookit Island was a quest for stories of unexplained mysteries that might look good in the Sunday supplement. Bowie and Teague obligingly trotted out a couple of campfire chestnuts for him, but now that they’re back at the office, Stephanie wants to know if they’ve ever actually stumbled across a real unexplained mystery, so they tell her about The Colorado Kid.

What brought the writer for the Boston Globe to Moose-Lookit Island was a quest for stories of unexplained mysteries that might look good in the Sunday supplement. Bowie and Teague obligingly trotted out a couple of campfire chestnuts for him, but now that they’re back at the office, Stephanie wants to know if they’ve ever actually stumbled across a real unexplained mystery, so they tell her about The Colorado Kid.

See, back in 1980, two local kids found the body of a man dressed in a suit, sitting on the beach, dead. Cause of death turns out to be asphyxiation: he choked to death on a piece of meat. Where the meat came from and where it went, how and when he had a fish dinner, and even a loose Russian coin rattling around in his pockets all turn out to be clues that lead down spiraling paths of conjecture that end nowhere. The only real break comes when a trainee coroner identifies the tax stamp on the Colorado Kid’s pack of cigarettes as being from Colorado, a breakthrough that yields an ID for the corpse after months of work.

But that leads to the biggest complication of all. Because based on the Kid’s movements and when he was last seen in Colorado, there’s no way he could have made it all the way to Maine in the time he had. Theories are floated—he chartered a private plane, UFO abduction, people are lying—but they all sink, one after the other and 25 years later, the mystery still stands. The book ends with Stephanie wondering at the mystery, and isn’t life full of mysteries that are so much more beguiling than their solutions. Cue state of wonderment, life is stories, we are all made of starstuff, etc. Kid is partially about two strangers from out west (the Colorado Kid and Stephanie) who come to Moose-Lookit Island and get adopted by the locals, but, like From a Buick 8, it’s also about how mysteries are sometimes more compelling than their solutions.

But that leads to the biggest complication of all. Because based on the Kid’s movements and when he was last seen in Colorado, there’s no way he could have made it all the way to Maine in the time he had. Theories are floated—he chartered a private plane, UFO abduction, people are lying—but they all sink, one after the other and 25 years later, the mystery still stands. The book ends with Stephanie wondering at the mystery, and isn’t life full of mysteries that are so much more beguiling than their solutions. Cue state of wonderment, life is stories, we are all made of starstuff, etc. Kid is partially about two strangers from out west (the Colorado Kid and Stephanie) who come to Moose-Lookit Island and get adopted by the locals, but, like From a Buick 8, it’s also about how mysteries are sometimes more compelling than their solutions.

It’s considered common knowledge that on some level fiction should aspire to reproduce reality. But fiction writers inevitably hit a moment in their careers when they realize that to replicate real life too closely is to bore the pants off their readers. Fiction requires motives, drama, resolutions, and compelling endings, all tendencies that real life resists. The first time fiction writers realize this is when they try to reproduce human speech and discover that if they do it too faithfully they just wind up with gibberish on the page. Later, that writer will discover the same is true for plots and characters. Kid and From a Buick 8 feel like King’s protests against the unreality of fiction, about how the needs of drama sometimes flatten the mysterious, beautiful, unknowingness of life.

The problem with Kid as opposed to Buick is that Buick is about a dead father and his son trying to discover what happened to him, while Kid is about a girl from away deciding to go fulltime with her summer internship because she loves Maine so much. One is a bit more emotionally compelling than the other.

The problem with Kid as opposed to Buick is that Buick is about a dead father and his son trying to discover what happened to him, while Kid is about a girl from away deciding to go fulltime with her summer internship because she loves Maine so much. One is a bit more emotionally compelling than the other.

From a Buick 8 brought one part of King’s career to an end. He had just recovered from being hit by a van, and so that book is suffused with pain and a sense that the world has ended. Kid is the first faint stirrings among the grave dirt, the twitching fingers that indicate the victim may not be dead yet. It’s a five fingered exercise, a little noodle on the piano keys to warm up his fingers, before King brings the world to an end—again, but this time for fun—in his next novel, Cell.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.