Welcome to Freaky Fridays, the last chance to rediscover the forgotten authors of the paperback originals boom of the Seventies and Eighties before all paper crumbles into dust and they’re lost forever.

The Seventies were a time when Americans abandoned the cities for the country, barely even stopping at the suburbs on the way out the door. All told, 1970-80 was the first decade since 1810-20 that rural counties actually grew faster than urban and suburban communities. This was the decade of white flight, when Americans abandoned what they perceived as dangerous cities and soulless suburbs to get back to nature and in touch with the land by moving to small town America.

What they found waiting for them were secretive, isolated gulags founded by Satanic painters, bloodthirsty fertility cults, and crazed religious sects. Sometimes they found hamlets that had built their town squares on Indian burial mounds or situated the local lunatic asylum over the site of a centuries-old massacre. It was a crisis in town planning that resulted in ancient curses, restless spirits, and bizarre rituals being unleashed on average Americans in unprecedented numbers. Books ranging from Harvest Home to The Curse to The Searing to Maynard’s House chronicled the carnage. Some writers, like Ira Levin, satirized the whole “Escape from Progress” project in The Stepford Wives. Others, like Ken Greenhall, took a considerably bleaker view.

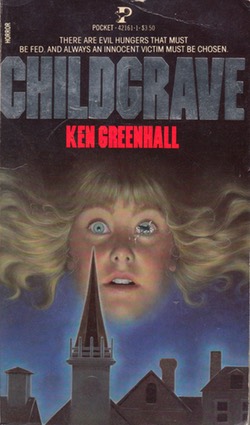

If there’s a forgotten master of horror fiction, it’s Ken Greenhall. With a mere six books to his name, two of them are classics of the genre (Elizabeth, Hell Hound), one is a near masterpiece of historical fiction (Lenoir), and two are interesting B-list material (The Companion, Deathchain). Then there’s Childgrave (1982), which I’m becoming convinced fits in more and more with Elizabeth and Hell Hound as one of the best, or at least most interesting, horror novels ever written.

A staff writer for encyclopedias, Greenhall was an intellectually restless polymath who graduated from high school at 15 and was as adept with making linoleum prints as he was with building his own harpsichord or solving a Rubik’s Cube in a single day. He only published paperback originals, and never got a fair shake from the publishing world, constantly excluded and forgotten (even by his own agent), given shoddy covers and no promotion by his publishers. And yet he delivered books that were each told from an eloquent, elegant point of view. He could say in a sentence what other authors struggled to articulate in an entire book, and stylistically he was a direct heir to Shirley Jackson.

He was also finely attuned to the market. Creepy kids were cleaning up thanks to The Omen novelization and a million imitators when he debuted Elizabeth, about a murderous 14-year-old girl. Next came Hell Hound, told from the POV of a killer bull terrier, right at the height of the killer animal craze (which had started with Jaws and The Rats in 1974). After those two pitch black books, he wanted to work on something lighter, and so he turned to Childgrave. The book started percolating in his mind when he picked up a copy of a book either about or by psychiatrist R.D. Laing (possibly 1977’s Conversations with Children) featuring a four-year-old girl on the cover. That sparked something, and he set to work.

Jonathan Brewster is a fine art photographer living in Manhattan with his four-and-a-half year old daughter, Joanne, who, when asked if she’d like to go see an album being recorded, tells her father she’d rather have another birthday instead. Jonathan is a life-long moderate who avoids strong emotion. As he says on the first page:

“I have always been devoted to moderation and the inexplicable. I am reassured by the Bermuda Triangle, and I admire the person who refuses the second drink. I read only the beginning of mystery novels, delighting in descriptions of oddly deceased victims discovered in locked rooms. When the detective says ‘Aha,’ I stop reading.”

Into his well-ordered world comes Sara Coleridge, a harpist he falls in love with after watching her play during an opera. The two seem destined for some kind of relationship, but Sara turns out to be as elusive as a ghost, vanishing at odd moments, making Jonathan swear strange vows, pushing him back, then pulling him closer with no rhyme or reason. With its precise descriptions of fleeting emotional states, as well as its upper-middle class, Manhattan-centric setting, Childgrave feels very close to literary fiction, despite the wintry air of the uncanny that hangs over everything. For much of the book, nothing supernatural happens and it’s impossible to decide what genre it fits into.

Usually a horror paperback declares its genre (vampires, haunted house, killer kids, urban blight) on the cover and there’s not a lot of mystery about where it’s going, simply varying degrees of pleasure in how it gets there. In this case, there’s not a clue about what we’re reading, so you feel your way forward carefully in the darkness, hands extended, senses strained for the slightest clue. The first one comes when Jonathan has Sara and Joanne sit for a series of portraits using his trademark camera obscura. What shows up on the negatives are specters, feathers, angel wings, the faces of the dead.

Joanne begins to talk about her imaginary playmate, Colnee, who eats raw meat and has a father dressed all in black who follows her wherever she goes. Colnee and her father look a lot like the figures showing up on film, and Joanne develops a passion for red meat, which Sara looks longingly at but refuses to eat. The pictures become famous and suddenly everything material Jonathan ever wanted is within his grasp, including Sara who shows up for a weird tantric sex session. Then, as Joanne puts it, everyone “goes away.” Sara disappears, and so do the spirits.

We begin to think that maybe we’re in a vampire book with all this talk about cannibalism and blood, especially after Jonathan tracks Sara down to her hometown in upstate New York, Childgrave, with its 250 residents living lives that seem unchanged by modern technology. The mystery deepens when Joanne falls in love with Childgrave and her new best friend there keeps saying, “I’m going to be with the dead little girls.” Then the world comes unmoored (“Sometimes bad things are good,” a resident says) and we fall through into yet another genre: the small town guarding dark secrets. In this case, it’s the secret of Childgrave’s holy communion.

When confronted with what’s happening Sara and Jonathan argue:

“But wouldn’t it be more civilized to do these things symbolically?” he asks.

“Perhaps,” she says. “But civilized people seem to end up playing bingo or having rummage sales. They’re more interested in frivolous pleasures and possessions than they are in God. Maybe God is not civilized.”

That’s the horror at the heart of Childgrave, a horror that takes a long time to manifest, but once on the page it’s adult and mature in a way that makes vampires and ghosts seem like ways of avoiding the subject. Jonathan can have Sara’s love, he can have a wonderful life, he can live a deeply spiritual existence, but it requires him to do unthinkable things. Or, and this is where it gets truly horrific, things that he previously found unthinkable. H.P. Lovecraft was the one who posited that the human interpretation of the universe was naturally prejudiced, and that much of its workings might be things we find incomprehensible, immoral, or vile. To put it more simply, as Johnathan says of Sara’s lifestyle. “It’s unreasonable.”

“Yes,” she simply replies.

Some things can’t be argued with, negotiated, or reasoned. They must be accepted, no matter how unacceptable. There’s an epilogue at the end of Childgrave that attempts to deliver the book back to the “lighter” territory Greenhall first envisioned for it. It’s almost as if he wrote this book in a clear, delicate, voice pitched at the highest level of artistry, a book that strays into uncomfortable territory, and then left his draft on the windowsill, the final page incomplete, for some passing hobgoblin to finish before they ambled away. But everything that goes before continues to make the case that Greenhall respected horror and thought it was capable of much more than simple scares. It was capable of asking questions that had no easy answers. Too bad that respect was never returned.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.

Grady Hendrix has written for publications ranging from Playboy to World Literature Today; his previous novel was Horrorstör, about a haunted IKEA, and his latest novel, My Best Friend’s Exorcism, is basically Beaches meets The Exorcist.