Compress 1200 pages into 1200 words at your own peril; I shall do my best to explicate the joys and occasional frustrations of reading Jerusalem, Alan Moore’s symphony to Northampton.

Imagine an exhibition about a single place, a hundred artists walking and painting in Monet’s garden, selecting portraits for an exhibition. And, after that exhibition a story is told about each painting, connected by the shared narrative fest of the space. Now, scatter these painters through time, and after death. The stir of a single life’s impetus becomes entwined with the movement of wind and grass and architecture.

This is not Monet’s garden, though.

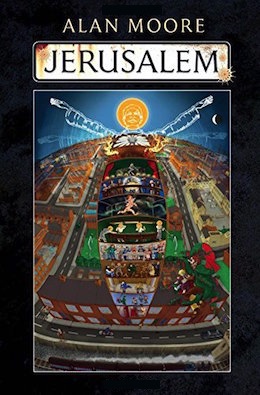

The rough and tumble government housing projects, pubs, and bollard-lined streets where the ruins of broken constructions, abandoned detritus of centuries of economic decline form the playgrounds for the local children, there. In this landscape, in the heart of England, an exhibition will occur, where paintings of the life and afterlife of the city will appear. The artist, a female stand-in for the author, depicts a series of judgments upon her city and her community in the form of paintings described in the final pages of the text. She paints scenes from her little brother’s near death experience.

Michael Warren, the brother, had once upon a time nearly choked to death when he was a toddler. As an adult, another near-death experience awoke, in him, the memories of his youth, when he journeyed through the afterlife with a gang of rascal ghosts, seeking out the clues to the mystery of Michael Warren’s guaranteed and fated return to the land of the living, and his role in the mythical “Vernall’s Inquest” that is so critical to the fate of all mankind, among the living and the dead.

You see, the two Warren siblings are of a line of prophet/artists known as Vernalls. Snowy Vernall, a grandfather, was a madman who climbed chimneys even as his daughter was being born in a gutter below. His father had been visited by an angel in the high reaches of a cathedral during a refurbishing job, and had his mind broken by the divine voices. Alma Warren, the descendant of these madmen prophets, is a foul-mouthed, self-proclaimed freak that made a fortune and a name painting book covers and comics, and acts as a beloved gargoyle as she makes her way around town. Her work becomes the judgment and the final word on the subject of the district, in the very final exhibition of the huge book.

Disjointed figures emerge early on in the novel, and can throw off a sense of cohesive narrative flow, but each section has a place and contributes to the larger story of the place in some fashion. The real story is the interaction with a lot of relatively small lives, lived quietly, with this huge scope of history that builds the foundation of a place. The monk that brings the fragment of the rood, by divine decree, has a small part to play.

So, too, does the ghost of a homeless “rough sleeper” named Freddy Allen, who made his living pinching bread and milk from door stoops until death found him in a similar homeless state. Unwilling to ascend to the higher reaches of time, he continues to wander the living world, in his way, invisible to all but the deranged and deeply drugged. Not the mythical Vernalls, and not the Warrens, just figures of the neighborhood, who had their moment touching the ground, making a small mark, and then passing on to the mystery of time, building their stories up and tumbling on top of each other like individual portraits in a gallery, becoming cohesive as certain main moments and narratives emerge through many eyes. A struggling, crack-addicted teenager is attempting to make enough money to buy another hit and survive another day. A ruined poet, long past his prime, walks to the pub and begs for money from a friend, and also encounters the young woman who seeks to sell herself. When seen from so many angles, the mundane events form an anchor that holds the reader in a moment in time, when so much else is disjointed.

Layered upon this moment in time, the rippling stories of the Vernall family, as it tumbles into the Warrens through Alma and Michael’s mother, who marries into the Warren name from Vernall, explicate the many tragedies and miseries and joys of life in Northampton, from casually meeting Charlie Chaplin, to the diphtheria quarantine camp that took a beautiful, young toddler off to die once the diagnosis was clear. The wars came. The immigrants came. The politicians came. The preachers came. And through it all, the Vernalls, and then the Warrens stand their ground, see everything, travel from the dawn of time to the end of time, and look in upon the coruscating jewels of lives lived.

At the end of the tale, the sheer scope of the voyage is breathtaking, but not without some perils along the path. A few of the sections are more challenging and inaccessible than others. The romp through the afterlife is very enjoyable, and readable, and a fascinating cosmology emerges. Many of the modern figures, in their moment, are interesting and enjoyable, but lack the color and adventure that invigorates the best of the book. The patchwork histories sometimes seem to veer off, in particular the nearly unreadable chapter from the point of view of James Joyce’s daughter, Lucia, will likely cause otherwise stalwart readers to choose to skim or put the book down for good. In an exhibition, after all, not every picture or portrait will be as pleasurable and invigorating as the others.

Yet, in the end, the whole scope of the ambitious work overrides the minor concerns that a few sections veer off into a corner, a bit. It is the corners of the text, in fact, that are often the most enjoyable. The explosion of text, like a bomb going off in the form of a novel, is a magnificent experience, and by the end, the reader will have seen a vision of the universe not unlike the sort of books that become holy, in time, in their way.

In every section of the novel there are phrases that seem worthy of pulling out, framing, taking in as a life’s motto. The idea that there is a global, continual holocaust of the poor, where poor families are pushed into cheap houses and walled off from the world, and they know it, resonates in our troubled times. The cosmos constructed, with Mansoul “upstairs” from what we perceive, and higher orders of being above that, is thoroughly well-constructed, and beautifully depicted. So much of a history of place, in other books and stories, is dedicated to characters like Oliver Cromwell, who won his kingdom in Northampton, once. That he is only barely present in the book, and old women who birth babies and prepare bodies for burial are more prominent than any king or hero speaks volumes to the truth of history depicted by Moore: The real history is the lives pushed one on top of another, each living with the ghosts and dreams that came before us, building a life out of what we have at hand.

Jerusalem is available from Liveright Publishing.

Joe M. McDermott is best known for the novels Last Dragon, Never Knew Another, and Maze. His work has appeared in Asimov’s, Analog, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet. His latest novel, The Fortress at the End of Time, is available from Tor.com Publishing. He holds an MFA from the University of Southern Maine’s Stonecoast Program. He lives in Texas.