Much has been said—over and over again and usually with well-intentioned sciolism—about those blasted Eagles in The Lord of the Rings.

There is actually precious little written about Tolkien’s imperious birds of prey, and I suppose that’s why it’s easy to armchair criticize the good professor for his use of them as eleventh-hour saviors. But that doesn’t mean there aren’t some important distinctions to make. And what’s not to love about giant raptors? Since the rocs of Eastern legends and Marco Polo’s apocryphal adventures, everyone is fascinated by the idea of big birds, right?

So to sum up everyone’s problem: why didn’t one of the Eagles just fly the One Ring straight to Mt. Doom, or at least carry Frodo there, and just be done with it? Or heck, why not a whole convocation of them? Some readers and nitpicky moviegoers regard this as some kind of plot hole… which I say is a load of horsefeathers. I will concede that, of course, it would have been nice if Tolkien had added—among other things—a couple of helpful lines to make it clearer that the Eagles were simply not an option for this task and that the characters in The Lord of the Rings understood this. But maybe he didn’t need to, since any attentive reading will reveal certain truths.

Sure, plenty of arguments can be made against the Eagles’ involvement, but none can really be substantiated. One theory is simply that such a gambit probably wouldn’t succeed. The Eagles, while mighty, aren’t necessarily powerful enough to storm Mordor even in great numbers—Sauron’s power has grown strong again and it’s pretty likely he could handle them if they entered his land. He’s nothing if not studied; he knows of the Eagles. Plus, the great birds are physically vulnerable to the bows of Men (as mentioned in The Hobbit), to say nothing of the darts of Orcs or the sorcery of Sauron’s other servants. And do you think the Eagles themselves would immune to the One Ring’s evil?

Still, that’s all speculation. If anyone’s really hung up on this head-scratcher, they might as well wonder why the Elves didn’t just use their deep immortal minds to discover thermonuclear power and invent fission bombs, then detonate them in Mordor? Because they didn’t and, more importantly, they wouldn’t. They’re asking for a fundamental shift in the nature of Middle-earth, its divine custodians, and its inhabitants. And that’s what I’m here to talk about.

Let’s make one up-front distinction. There are the films, and there are the books, and both are awesome in their own right. Now, as much as the films do change some things rather drastically—Faramir (he does the right thing from the get-go!), Osgiliath (we don’t even go there!), the time of Saruman’s death (too soon!), etc.—I’m pretty sure not using the Eagles can be justified simply by saying… because the books didn’t. Which is to say, adding the Eagles in a transport capacity would be a game changer bigger than anything else and would have doomed the films by betraying the books way too much. Tolkien himself balked at the idea when he read and rejected a proposed film script in 1958 that tried to increase the Eagles’ role.

Oh, and side-note for anyone who hasn’t read the books: the Eagle-summoning moth that Gandalf wizard-speaks with is an interesting visual device, but it’s got no literary tie-in. If anything, it muddies our idea of who the Eagles serve. It seems like Gandalf can summon them in that moment—when really, he can’t. Even the Grey Pilgrim has nothing to do with their sudden arrival at the Black Gate in the third book/film.

So the short answer, concerning the books, is what’s found in the pages of The Lord of the Rings, which is scant wordage indeed. The extended, deeper answer lies in The Silmarillion and books beyond, where the identity and origin of the Eagles is addressed—at times in passing, at times directly.

But let’s start chronologically in the real world. The Hobbit came out in 1937, when Middle-earth at large was still just baking in the oven. Here our feathered friends are depicted a bit more simply, even more surly. When they first show up, Tolkien writes straight-up: “Eagles are not kindly birds.” They don’t even bear the capitalization later attributed to their race. “Some are cowardly and cruel,” he adds, and it was only the eagles of the northern mountains which are “proud and strong and noble-hearted” at all.

They only save Thorin and Company in what feels like a deus ex machina move because they are “glad to cheat the goblins of their sport,” and because their boss—the otherwise unnamed Lord of the Eagles—commanded them to. He alone is friendly with Gandalf. Not until the end of that episode does Bilbo, our POV protagonist, realize that the eagles aren’t actually the next threat, and that he won’t be devoured after all. The eagles aren’t gentle with the group and they explain themselves little. While the dwarves are clasped in eagle talons, Bilbo has to grab onto Dori’s legs just in time to be saved at all, forced to cling on to the dwarf’s legs for dear life the entire flight.

Gandalf convinces the eagles to carry them a bit further than just their mountain eyries (which aren’t especially convenient to climb down)—and only the Lord of the Eagles has the sensitivity to order his friends to fetch food and firewood for them. The great birds outright refuse to carry the company anywhere “near where men lived,” because they know they’ll get shot at. Because men would—very reasonably—think the eagles were stealing their sheep. Because they’re giant freaking birds of prey and even talking birds are going to eat other animals (whether those others can talk or not). Hey, this ain’t Narnia.

Yes, the eagles do join the Battle of the Five Armies at the end of the book, because they do hate the goblins, had spied their mustering in the Misty Mountains, and so opportunistically choose to join in on the goblin slaughter. They aren’t there, like the wood-elves or Men, for any portion of Smaug’s loot. They were just happy to make there be fewer goblins in the world. Everyone, but everyone, agrees that goblins suck. Remember, if not for the goblins, the elves and dwarves would have come to blows. And clearly eagles and Men have been at odds before. Not everyone plays nice in Middle-earth, not even the good guys. Just ask The Silmarillion! So then, after the Battle of the Five Armies is won, Dain Ironfoot crowns “their chief with gold” and then the eagles fly home. And that’s that.

Now fast forward through time to The Fellowship of the Ring, where by this time Tolkien has given the Eagles their capital E. They’re still not active participants in Middle-earth’s daily affairs—they never are. They’re not flying all around doing good deeds, saving the day willy-nilly, and rescuing cats from trees. (I bet they ate a few cats, though.) At most, we learn that the Eagles “went far and wide, and they saw many things: the gathering of wolves and the mustering of Orcs; and the Nine Riders going hither and thither in the lands; and they heard news of the escape of Gollum.”

They are the eyes in the sky—but why, and for whom? Well, at this time, they did much of their spy work at the request of Radagast the Brown, the animal-loving wizard who is friends with birds above all. The wizards, while it’s never really spelled out in such terms in this book, are plugged into greater powers and have an active interest in the movements of Sauron and his minions. And later, Galadriel herself—whose power and history are great indeed—is able to request the help of Gwaihir, “swiftest of the Great Eagles” in seeking Gandalf’s fate.

In the persnickety why-didn’t-the-Eagles-just-do-X argument, I always come back to what Gwaihir says to Gandalf when he picks him up, “un-looked for,” at the pinnacle of Orthanc. It clues us into the nature and purpose of his race. Gandalf later recounts this aerial exchange at the Council of Elrond in Rivendell:

‘“How far can you bear me?” I said to Gwaihir.

“‘Many leagues,” said he, “but not to the ends of the earth. I was sent to bear tidings not burdens.”‘

Which is kind of perfect. It’s succinct, maybe even a bit crass, but it’s actually all that really needs to be said. “Look,” Gwaihir is basically saying, “Since I’m here, I’ll help you get to point B, but I won’t solve all your problems for you.” If the Windlord says he’ll fly you many leagues—leagues are usually three-mile increments—he’s not saying he’ll fly you all of the leagues. Eagles don’t write blank checks.

At this point in the story, Gandalf already knows about the One Ring and is pretty rattled by Saruman’s betrayal. Things are looking bleak, and he sure could use any help he can get. Yet he doesn’t say to Gwaihir, “Oh, hey, since we’re on the subject of rides… any chance you could also fly a hairy-footed little buddy of mine to Mordor?” It’s already off the table in Gandalf’s mind—not to mention it hasn’t even been decided what to do with the One Ring. And I like to think that Gwaihir, although he’s obviously fond of the two good wizards, is a cranky bird; Gandalf isn’t going to rock the boat.

At the Council of Elrond, when all topics and ideas are being tossed up to see if they stick, at no point does anyone even suggest the Eagles. It’s like they all already know not to bother. They get it, even if we don’t. And it’s not like they aren’t already entertaining crazy ideas. To show you how desperate the good guys are feeling with the One Ring in hand, Elrond even suggests going to Tom Bombadil, like, right there in front of everyone even though most in attendance have no clue who that is. And it’s Gandalf, who arguably knows more about the major players than anyone else present, who dismisses bothering with that deranged but powerful woodland hobo. Tom isn’t responsible enough, or ultimately invulnerable enough, to trust with such a weighty piece of jewelry.

And all the talk of getting the Ring somewhere else—to Tom, to the depths of the sea, wherever!—also comes with talk of the sheer danger of the journey. And secrecy! Sauron’s spies are everywhere. There is the omnipresent fear of all roads being watched, and Gandalf’s colleague Radagast isn’t the only one with birds for spies. Sauron and Saruman both use beasts—“Crebain from Dunland!”—and Gandalf worries about both crows and hawks in the service of their enemies. The Eagles aren’t sky ninjas. If you’re an Eagle, you’re big and bold and grand. You make entrances and big screechy swoops. It’s what you do.

So aside from their lofty surveillance up till that point, and later Gandalf cashing in another of his Good For One Free Eagle Ride coupons at the mountain peak of Zirakzigil, the great birds play no more part in the tale until the end. When the One Ring is destroyed, when the borders of Mordor don’t matter anymore, when the peoples of Middle-earth have already come together… then do the Eagles arrive in force to turn a pyrrhic victory into a better one.

Oh, your army is being squeezed by the legions of Mordor at the Black Gate in the great battle at the end of the Third Age? Oh, the Nazgûl are also harassing you? What, they’re riding upon winged beasts that were nursed on fell meats?! Holy heck, yeah, we’ll help with that! And what, your little Hobbit friends have already snuck through the Land of Shadow and up into Mt. Doom and then dropped that vile-ass Ring into the fire? Okay, sure, we’ll get them out!

So this brings me to The Silmarillion, where we are told that the race of Eagles are first “sent forth” by Manwë, the sky-themed King of the Valar and viceregent of all Arda (a.k.a. all known creation). The Valar are essentially the gods, or archangels, of Arda, though they’re certainly never given that label. We read that “[s]pirits in the shape of hawks and eagles flew ever to and from” Manwë’s halls, and that he, quite unlike his wicked brother Melkor—who becomes Morgoth, Middle-earth’s Lucifer figure—is all about ruling in peace and selflessness.

Now, the Eagles are set up to “keep watch upon Morgoth; for Manwë still had pity for the exiled Elves. And the Eagles brought news of much that passed in those days to the sad ears of Manwë.” Think of them as heaven’s news ’copters, ever reporting the tidings of Middle-earth back to their boss, who is not an omniscient, all-seeing being. Owing to their origins, it’s also evident that the Eagles are an immortal species, or at least the early ones were. In some accounts (namely The War of the Jewels), it’s suggested that Gwaihir himself might have been one of the Eagles in the First Age, which would make him one of the few beings of those days who also shows up in The Lord of the Rings . . . you know, many thousands of years later!

In the very early days of creation, when Yavanna, the Queen of the Earth, first supposes that the Eagles would live in the great trees that she plants, Manwë corrects her. “In the mountains the Eagles shall house, and hear the voices of those who call upon us.” Meaning they’re also prayer-hearers as well as reconnaissance agents. So actually, given their special place in the scheme of things—spirits in physical bodies, sent to lair in aeries on Middle-earth and not in more celestial estates—the Eagles are more like Manwë’s special ops. Intelligence agents who also do some special rescue missions, with some sporadic Orc-slaying thrown in.

Another description can be found in Morgoth’s Ring, volume 10 of The History of Middle-earth, wherein Christopher Tolkien organized many of his father’s annotations, notes, and further thoughts. In a chapter on Aman, the Blessed Realm, where all Elves long to be but many (the Noldor) are exiled from, there is this excerpt:

‘They forbade return and made it impossible for Elves or Men to reach Aman—since that experiment had proven disastrous. But they would not give the Noldor aid in fighting Melkor. Manwë however sent Maia spirits in Eagle form to dwell near Thangorodrim and keep watch on all that Melkor did and assist the Noldor in extreme cases.

Maiar are the “lesser” spiritual beings situated in the hierarchy beneath the Valar. The Istari wizards, the Balrogs, and even Sauron himself are all Maia spirits. It’s a spectrum; not all are of equal power, and of course Sauron is clearly one of the mightiest. The implication is that all the great Eagles may be spirits first, yet they do inhabit beast form and are animals in many respects. Even though they can speak as some other animals have shown in Tolkien’s legendarium, Morgoth’s Ring states that they had to be taught to speak; it does not come naturally to them.

Even during the epic events of the First Age, the Eagles are used sparingly, whisking heroes and royals out of peril—and on several occasions, dead bodies!—usually when said heroes already did the valiant or foolish things they had set out to do. Sound familiar?

In one memorable example, we read in the chapter “Of the Return of the Nolder” that Thorondor, “mightiest of all birds that have ever been,” is sent as an insta-reply to the prayer-like cry of Fingon. See, Fingon, an Elf prince, goes searching for his lost friend, Maedhros, eldest son of Fëanor (of Silmaril-creating fame). He at last finds Maedhros chained by one hand high up on the edge of a mountain face. He was bound there by Morgoth as a hostage, and had languished in torment for a long time. By some reckoning, even a few years. Yeah, Elves in those days were especially hardy!

But instead of having his liver devoured by an eagle every day like the poor Greek Titan this scene is obviously inspired by, Tolkien—who loves to invoke and then twist choice moments from real world mythologies—uses an eagle as the Elf’s salvation. When it’s evident that Fingon cannot climb to his friend to save him, Maedhros pleads for death instead. He asks Fingon to slay him with an arrow. So Fingon, grieved of what he must do, cries out to Manwë:

O King to whom all birds are dear, speed now this feathered shaft, and recall some pity for the Noldor in their need!

Right away, this supplication is answered—not with the mercy-killing accuracy he was hoping for but with a flesh-and-bone and many-feathered beast! Thorondor swoops down from the sky—presumably saying, “Whoa, chill with the arrow.”—and flies Fingon right up to his chained-up buddy. Even in that moment, the Eagle doesn’t just solve their problems; he’s just playing flying carpet for them. Fingon is unable break the shackle that binds Maedhros to the mountain, so Maedhros again pleads for mercy killing instead. But nope, Fingon got this far with the Eagle’s help and refuses to kill his friend. So he does what a lot of Tolkien’s badass characters do: he maims a guy. Maedhros’s hand is hacked off at the wrist, allowing him to escape the bond. Then the Eagle flies them both back home. It makes all the difference for these two Elves, but the heavy-handed divine intervention that the Eagles represent is always… just so. A lift here, a flap there, a short-lived flight from B to C. Never A to Z.

In another chapter, Thorondor again comes screeching down from the mountain just when Morgoth is about to break apart the body of Fingolfin—the High King of the Noldor, who he’d just slain—and scratches the Dark Lord right in the face! And it totally leaves a scar. Good bird!

In yet another scene, Thorondor and two of his vassals (one of whom is our pal Gwaihir) spot Beren and Lúthien after the famous interracial couple collapse wounded and weary from having just taken Morgoth to the cleaners in his own lair. Always the Eagles are held in reserve, watching, reporting when they’re asked to—and sure, dive-bombing Orcs and other nasties when they can fit it into their schedules. Always with a view towards helping out the Noldor, whom Manwë has a soft spot for throughout The Silmarillion. Yes, in short, when the Eagles swoop in it’s because Manwë pitied the fools.

Finally, Thorondor and seemingly all his vassals do take part in the War of Wrath, unquestionably the largest battle that ever takes place in Middle-earth. It’s the one where basically everyone, including the Valar, team up against Morgoth and his monstrous legions to finally put an end to his dominion… though, of course, not of all the evils he’d sown. There are heavy losses across the board. The Eagles, in this epic showdown, notably show up to help take down all of Morgoth’s remaining dragons, which he’d unleashed all at once. Think massive bestial dogfight, a “battle in the air all the day and through a dark night of doubt.”

In the Second Age, the Eagles adopt a cooler and somewhat more figurative role. Morgoth has been replaced by his chief lieutenant and future ring-making successor, Sauron. After waging nasty wars with the Elves, Sauron allows himself to be captured by the Númenóreans—that noble and long-lived branch of Men from which Aragorn is descended—and worms his evil counsel into their power-seeking mortal hearts. As a “repentant” prisoner, he becomes their puppetmaster and inspires them to wickedness and deadly hubris. The rulers of Númenor then turn their eyes upon the Valar in the far west and become convinced that they can conquer them. Sauron, ever a deceiver, has them believing that the Valar jealously hide the power of immortality from Men. Falling for Sauron’s lies hook, line, and sinker, and thus believing that the Valar can be overcome by sheer force, the Númenórean king begins to plot against them. And with him most of his people.

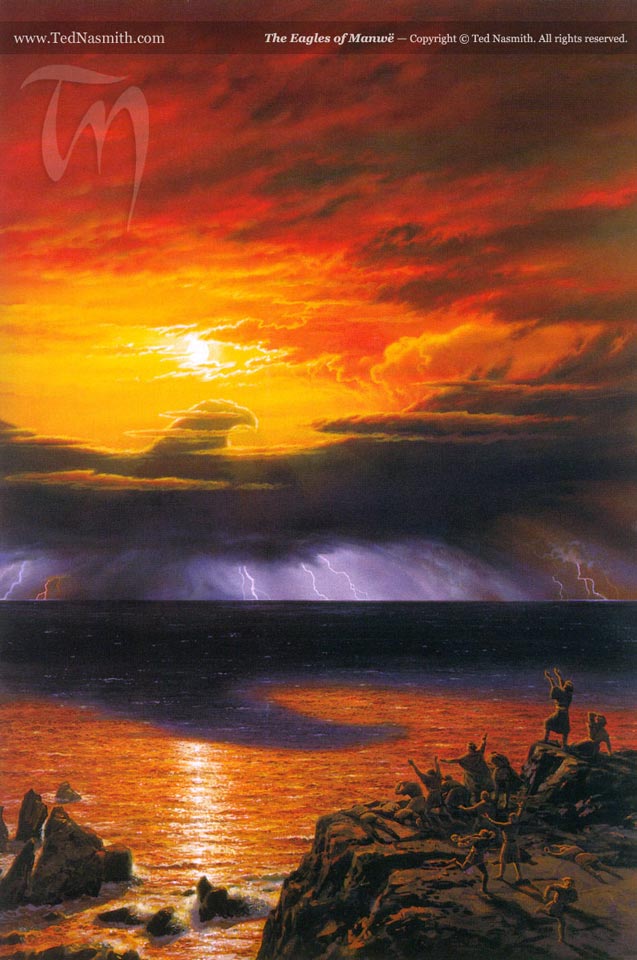

And that’s when the weather, which was always so perfect in Númenor, begins to darken. From the western horizon—beyond which Valinor lies—a colossal cloud appears, “shaped as it were an eagle, with pinions spread to the north and the south… and some of the eagles bore lightning beneath their wings, and thunder echoed between sea and cloud.”

Here we see a meteorological manifestation of the Eagles, not the birds themselves, formed as if in warning. A scary-ass omen in the sky. Accordingly, many freak out. Those weren’t bear-shaped clouds, nor shark, nor honey badger. Those are goddamned eagles, and anyone know knows anything at all about the Valar knows who is represented by those great birds of prey.…

‘Behold the Eagles of the Lords of the West!’ they cried. ‘The Eagles of Manwë are come upon Númenor!’ And they fell upon their faces.

So while the Valar give fair warning, and the weather worsens and lightning even slays some people in hills, fields, and city streets, the power-hungry Númenóreans only get angrier and more defiant. But the fate of Númenor and its many repercussions are a whole different story, and lead to some serious geological fallout.

If you accept that the Eagles are more divine agents than courier service and yet you still wonder why the Valar didn’t just send them to find Sauron’s misplaced ring in the Third Age, and save everyone a heap of time and trouble, then carry it up to the volcano, it’s important to note that in Tolkien’s legendarium the gods, such as they are, take a very hands-off approach to the world. One could argue, and many have, that this expresses some of Tolkien’s own religious beliefs—which were strong but also tastefully understated. If there is a God, he allows the world to manage itself, choosing to inspire good deeds instead of having them carried out by divine agents.

As for Middle-earth, the Valar are not entirely idle. At the end of the First Age, they come forth to help give Morgoth the boot. And in the Third Age, remember that they do send some divine begins into the world with the express purpose of challenging Sauron when he proves almost as troublesome as his old boss had been. They do so by sending a tiny boatload of angelic (Maiar) beings in threadbare guises, downgraded for their mission into the bodies of old men with earthly needs (food, sleep, etc.). They are forbidden from using their full might—and only one of them, good old Gandalf, really even sticks to this one job.

Incidentally, as I mention in my essay on Saruman, there is a section in The Unfinished Tales where Christopher Tolkien relates from his father’s notes a scene wherein Manwë himself, who favored the airs and winds of Arda, directly volunteered Gandalf for the Saving Middle-earth gig that he and the other Istari are given.

Is it any wonder, then, that the Eagles, when they do show up in Third Age events, usually do so where Gandalf has already rallied his squishier friends to take on the forces of evil? Twice in The Hobbit the Eagles come to the rescue, even bringing beak and talon to bear in the Battle of the Five Armies to help turn the tide. In The Lord of the Rings, Gwaihir himself shows up three times: (1) saving a wizard from the clutches of another, (2) whisking the same wizard from a mountaintop after he’s been reborn, and (3) helping out at one more battle before saving a pair of Hobbits from rivers of fire.

As Gandalf relates after being picked up that second time:

‘“Ever am I fated to be your burden, friend at need,” I said.

‘“A burden you have been,” he answered, “but not so now. Light as a swan’s feather in my claw you are. The Sun shines through you. Indeed I do not think you need me any more: were I to let you fall, you would float upon the wind.”

‘“Do not let me fall!”I gasped, for I felt life in me again. “Bear me to Lothlórien!”

“That indeed is the command of Lady Galadriel who sent me to look for you,” he answered.

So are the Eagles a deus ex machina? Eh, sort of, but that’s not exactly how Tolkien thought of it. A deus ex machina is a too-convenient, unbelievable, and out-of-left-field sort of plot device that’s more for getting the author out of a jam than telling the reader a good story. Yes, the Eagles turn up “un-looked for,” but they’re still a known part of the world, creatures with a rare but established precedence for showing up in pivotal moments, and they do bring positive outcomes by design. Specials ops!

Tolkien coined a term: eucatastrophe, “the sudden happy turn in a story which pierces you with a joy that brings tears,” and he regarded it as “the highest function of fairy-stories.” That’s maybe a tall order in the jaded contemporary fantasy of today, but I still buy it. And it’s worth mentioning that The Lord of the Rings always has been a shining example of the old-timey fairy-story Tolkien was such a fan of, but he still pulled it off without it being goofy.

So again… why didn’t the Eagles just fly a ringbearer to the fires of Mt. Doom? Because these majestic birds aren’t someone’s pets. They’re an elite agency that may or may not get called in at any time—and not by just anyone. Sauron and his Ring are Middle-earth’s problems. But at least Gandalf, the only responsible wizard, specifically sent by the Valar to help it deal with its Dark Lord trouble, was permitted to receive occasional aid from the Eagles. And so he did.

But still, not often. Only in true need. Gandalf roams Middle-earth for about 2,021 years, and as far as we know, in all that time he doesn’t even ask for the Eagles’ help but for a couple of times.

Ultimately, these birds are about the joy that accompanies the exclamation, “The Eagles are coming! The Eagles are coming!” We’re supposed to have forgotten about them until the moment they arrive, in that final hour when we’ve nearly won the day! But even in winning, death can still be the likely outcome. Like when Gandalf realizes the One Ring has been destroyed, and Sauron defeated, he knows Frodo and Sam are in trouble and he so he turns to his cranky bird friend.

‘Twice you have borne me, Gwaihir my friend,’ said Gandalf. ‘Thrice shall pay for all, if you are willing. . .’

‘I would bear you,’ answered Gwaihir, ‘whither you will, even were you made of stone.’

I only wish there was more banter, more Eagle-and-wizard bromance camaraderie to read about. In any case, having said all this, I know there will always be those who squawk about the Eagles’ saving-the-day antics as if it was a problem.

And still those voices are calling from far away.

Jeff LaSala is a production editor and freelance writer who can’t leave Middle-earth well enough alone. He also wrote some sci-fi/fantasy books and now works for Tor Books. He knows that in addition to Thorondor, Landroval, and Gwaihir, a few of the other Eagles are probably named Don, Glen, Bernie, and Randy.