Disgraced government operative Colonel Chu is exiled to the flooded relic of New York City. Something called the Light has hit the streets like an epidemic, leavings its users strung out and disconnected from the mind-network humanity relies on. Chu has lost everything she cares about to the Light. She’ll end the threat or die trying.

A former corporate pilot who controlled a thousand ships with her mind, Zola looks like just another Light-junkie living hand to mouth on the edge of society. She’s special though. As much as she needs the Light, the Light needs her too. But, Chu is getting close and Zola can’t hide forever.

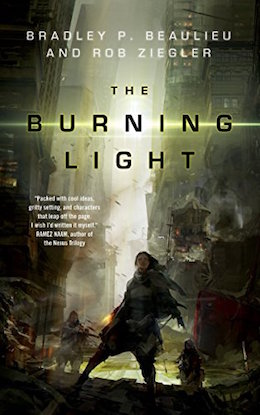

Available November 1st from Tor.com Publishing, The Burning Light is a thrilling and all-too believable science fiction novella from Bradley P. Beaulieu and Rob Ziegler, the authors of Twelve Kings in Sharakhai and Seed.

One

We Want the Vector

Three months ago…

They came to the first junkie at a landing maybe fifteen floors up. Matted hair hid her face; geologic layers of filth caked her skin. She sat cross-legged and blissed like some old ascetic on a mountain. She stank.

Solaas leveled his carbine at her. Goggins moved to grab her. The woman was oblivious.

She was tapped in, burning in the Light.

Colonel Melody Chu’s mind reached out to her troops, her words an electric flicker of pure thought:

Don’t even bother with her. She’s just a junkie. We want the vector.

A column of bramble and vine grew up the stairwell to a hole in the roof, a pale coin of light far above. Chu and her Gov troops continued to spiral upward, up, up, up, sweating in mirror black graphene armor, lugging their electromag carbines. Four months here, and Chu knew this was what they would all remember. The Sisyphean grind of climbing these old towers, the saturating miasma of sewage rising off the canals below. New York was a ruin of shit and stairs.

My point is, Chu said as they climbed, those old religions were on to something. I like sin. I like the idea of it. They’d passed a street preacher outside the building, his little boat moored to the top of a light pole protruding a few inches above the canal’s brown surface. In it he’d stood, bearded and wild. He’d gleamed with a wrath verging on joy, and ranted at them about Jesus. Jesus and salvation and Hell—his mind had reached out, briefly connecting, flashing images of crucifixion and fire. It had gotten Chu and her XO, Lieutenant Holder, talking.

Some of that God stuff’s alright. Holder’s mind leaned against Chu’s, a perpetual offering, sharp as a blade and poised, awaiting her command. He was small, but solid, dedicated, the only one of her troops not raised in a Gov soldier collective. It was why Chu had chosen him. The others, their empathy had been groomed out of them—but not Holder. And empathy, Chu figured, was a useful compass, even if sometimes it got in the way. It was their mission to save people, after all…

Holder’s words came as a shuffle of memory and thought as he followed her silently up the stairs. There was a worship group up in the woods not far from my collective growing up. Mostly Amish, I think, but they’d thrown together pieces of the Koran and the Gita, too, and some of the other old books. Nice people. Weird, no doubt, tapped in to each other nonstop, feeding each other verses. No conversation even, just pure scripture. You’d run into them on the road or someplace and it’d be this biblical feedback loop. Crazy. Good folks, though, real decent, all about service and compassion, shit like that. Always helped us pull in our wheat. He reflected for a moment. Made great cheese.

I don’t mean the stories, Chu told him, Jesus and Allah and God. I don’t care about God.

A-fucking-men, chorused several of her troops, and dry chuckling broke their silence. Four months their minds had been connected. They’d begun to share the same sense of humor.

I’m talking about sin, Chu said. Sin I get. Sin and repentance. Sin and salvation. Right and wrong. Consequences. Punishment. Her mind opened to Holder and her troops. She let them feel her certainty, wrapped them into her personal memory of the street preacher—railing at them from the far side of a madness built of brimstone and visions of angels, but righteous, brimming with his cause, fierce.

Chu related to the man.

We are standing at the edge of the end of the world, she said.

She knew her reputation within the Gov collective. Captain Ahab Chu. She’d brought down whole collectives, and many of her superiors thought she was too quick on the trigger—especially after Latitude. When Latitude had come down, it had hit everyone where it hurt: in their balance sheets.

Obsessive. Precipitous decision making. These were the assessments made by functionaries higher up the food chain. After Latitude, Chu had presented her superiors a real problem. The abrupt extermination of six thousand people had struck them as… an overreaction. Yet no one could argue she wasn’t effective.

They’d solved it by promoting her. After Latitude, they’d given her carte blanche to pursue the Light wherever it turned up—but with only a single squad: eleven washouts and Holder.

For her troops it was exile, far from the upriver promised land of cush overwatch postings in bloated finance and trade collectives, where the pay was good and the bribes were better. Exile, and her troops knew it. But Chu had won them over, cajoled them, harangued them, overpowered them with mission focus. She had personally stared into the Burning Light—and the Light had stared back. She knew it was coming. As they climbed the stairs, Chu let her troops feel it:

I have seen the Light! And the Light was no white whale. It was a shark, a marauder. In her bones Chu knew this. And her troops, they were not outcasts. No, they were righteous. They were her crusaders. They gave her Amens!

Why’s the Light got to chew on all these stankass junkies down here in New York? Solaas lamented. Chu felt his fatigue, heard his ragged breath echoing in the stairwell.

Moron, came Goggins, it doesn’t pick them because they’re junkies. It makes them junkies.

Yeah, well, it’d do my esprit de corps a shitload of good if it showed up once in a while in some posh Montreal whore collective.

Amen!

Goddamn.

I’d fight that fight.

If the Light showed up in a whorehouse, Solaas, Holder said, we’d have to reassign you on ethical grounds.

Why’s that, Chief?

Gov doctrine specifically prohibits interfamilial combatants.

I don’t get it.

Couldn’t very well have you fighting your mother, now, could we.

You know my mother, Chief? A sly flicker played across Solaas’s mind. Are you my father?

Fucking A right. and I’m gonna whup your ass, son, you don’t get up those stairs. Like sunlight off water, the joke reverberated among them, laughter playing across their minds, pushing the incessant churn and turn of the stairs to the background. Then it faded, the joke, the laughter, replaced again and always by the stink, by the grind, by the eternal climb.

That mean I get to call you Daddy?

Chu let herself smile.

* * *

They found the vector on the thirty-first floor. By some miracle the level hadn’t been stripped by scavenger gangs. It was a maze of glass, steel, stained drywall, and rotted industrial carpet—a moment two centuries old frozen in time, unpeopled, caught in perpetual nightshift.

It was what passed as a security team that gave up the vector’s position.

Goggins, on point, extended the spy eye, a black glass marble on his flat palm, beyond a blind corner. Its vision of the hallway beyond filled the minds of Chu and all her troops.

Well this is something new.

Through the spy eye, they all saw: four young bangers crouched around a lantern before an empty doorway. They were shirtless, tatted up with ink—not junkies themselves, just hired hands, hustlers getting paid for a night’s work, AKs slung over shoulders or propped against the wall. Two played dice, the other two passed a joint back and forth. The apotheosis of readiness and discipline. Chu almost felt sorry for them.

We got the drop, Holder figured, no problemo.

Chu unbelted a flash disc, the size of an old silver dollar her father had shown her once. Her mind touched her troops, calm, emphatic.

Goggins. Solaas. High, low. Go on the flash. Professional groupings, nice and tight.

Chu rolled the disc down the hallway. Lightning flashed. Thunder pounded the air. Goggins and Solaas stepped around the corner, Goggins high, Solaas low. The pock!-pock!-pock!-pock! of hypersonic ceramic rounds scorching the air lasted less than a second.

Clear!

Chu stepped around the corner. Through a curl of white smoke she saw the bangers, all four of them shredded, utterly still.

Good work. Her mind leaned against Goggins and Solaas, laying on the positive vibes, like scratching two cats behind the ear.

The room beyond had once been a bathroom—robbed now of all its porcelain and stalls, just a hollow square with holes in the floors and walls where piping had been stripped. The vector sat there on the floor.

It isn’t Zola, Chu observed. Holder gave her a look and she immediately regretted showing her disappointment.

No, Colonel Ahab, that is not your girl from Latitude. But a vector’s a vector, correct?

Chu swallowed bitterness. You are correct.

Just a kid. Goggins knelt beside the vector as the troops gathered up. Can’t be older than nine.

Goggins wasn’t joking. The boy was barefoot, starved-looking in a stained T-shirt so big it reached his knees. Like the junkie they’d encountered below, he sat lotus, unaware of the troops standing over him, his mind deep in the Light. He was the anchor, the physical center around which the other junkies had arranged themselves in a sphere throughout the building. A halo, they called it. Through the vector, this kid, they connected to the Light.

Just a kid… , Goggins repeated, distantly this time, and Chu realized he was reaching out to the boy, testing his limits even as the boy was touching the Light.

Goggins! Filter up! Chu ordered. We take no chances in this unit.

Yeah, dipshit. Solaas slapped Goggins’s shoulder, hard. Don’t get any on you, man.

It was true. Chu knew from experience. The Light had touched her once. The memory wrapped her psyche like enflamed scar tissue. A memory she’d shared with her troops so they’d understand what they were fighting, and why.

Joy had been a kid too, like this boy. And like this boy she’d sat at the center, within a little paper-walled classroom. A spontaneous halo, they’d called it. Bodies lay all around her. Chu’s teachers, friends, her parents. Gov troops who had come to the scene. Bodies, fallen over one another like fish dropped from a net. Dozens of them.

Her sister had surveyed the death, and her eyes had belonged to someone else, empty except for curiosity. When she’d seen Chu, standing stunned at the doorway, she’d smiled beatifically and lifted her hand, beckoning for Chu to come closer. And then the Light had reached out—

Chu drew the pistol from her hip.

Colonel! Holder reached out a hand to stay her, but not quick enough. Chu pressed the barrel against the kid’s forehead as the memory washed over her. Moments ticked past. Her troops watched her. Her hand trembled.

The kid opened his eyes. He gazed up at Chu, the same empty-but-clear expression worn by ancient Buddhist statues. The same expression Chu’s sister had worn. He smiled.

“I remember,” he said. “I remember you.” Chu felt it: the lighthouse strobe at the edge of her consciousness. It pulled her, grew brighter, tickling those places where she was most vulnerable, those places torn by loss.

A warm sensation rose up within her. The Light reached out, full of promise—

Chu raised the pistol and clubbed downward, hard and fast, clocking the kid across the temple. He went instantly limp. Chu holstered the pistol, then turned and walked away, her troops parting before her storm. For the first time in days, she spoke aloud.

“Bag the little fucker.”

* * *

When Chu and her troops returned to canal level, junkies were still fleeing. They clambered into homemade canoes and kayaks, gondolas, old rowboats into which they’d jerry-rigged sails. They cast looks over their shoulders at the Gov troops; the fear in their eyes made Chu laugh.

Her troops ignored the junkies. Their boat, a sleek katana-class interceptor, was tied to an old flagpole protruding from the building’s side. With its black diamond-plate decks and miniguns and electric props, it was like a barracuda here in the old city, a thing of startling wealth and ingenuity, of predatory speed. Goggins and Solaas hauled the vector aboard, stuffed into a black canvas bag, inside which he’d begun kicking.

Take him below, Chu told them. Give him another injection. Make sure he’s out. In a day, maybe two, they’d give him to their contact a half-day up the Hudson, who in turn would pack him in a Gov transport and send him west, for Grandma and the scientists she kept in her employ.

The street preacher still stood in his little boat. He yelled at the sudden exodus of junkies, yelled at the emerging troops. He lived for moments like this, Chu was pretty sure, the transient illusion of a flock to shepherd.

You know what scares me? she asked Holder. They stood side by side against the katana’s deck rail. Every time I catch a glimpse, every time I feel the Light, it’s just like when I was a girl, seeing it for the first time. I want to go in. I want to let it take me, just like it takes these fried-ass junkies. Even after everything we’ve seen, I still want it. How do you fight something that makes people want like that? How did you fight sin?

For once, it had begun to rain. A wall of cool mist had boiled up out of the Atlantic and now it swept north, swallowing Manhattan’s old square monoliths in a blanket of white.

I hate this city, Holder said finally, beads of mist clinging like mercury to his crewcut. He gazed up the canal, a canyon of vine-wrapped ruins. Chu followed his eyes to where larger, faster boats—boats with multiple sails and rows of oars—had appeared from around a corner a few blocks up. They’d begun to close on the fleeing junkies.

Labor traders.

They’d gather up the junkies and sell them off to the scavenger gangs, to whore shops, to black-market ship captains. The ones too weak for work, they’d dump overboard. Groups of these traders had begun tailing the katana: where Chu and her troops went, junkies fled like rats.

It’s no wonder the Light shows up here, Holder said. A single patrol for the whole city… how many halos you think are going on right now?

The source says nine. But we won’t reach any of them in time.

Exactly. We pop one, three more spring up in its place. We’re rowing against the current here. Holder sucked his teeth. Maybe Grandma can pull a string or two, get us some more troops?

Grandma burned her bridges keeping me out of the stasis tanks after Latitude. She doesn’t have any strings left to pull.

The oversight committee then?

They’d have to believe there’s a credible threat. Chu gave Holder a look. They haven’t seen the Light.

Up the block, grappling hooks flew. The Labor boats began reeling in the smaller junkie boats. There was yelling. There were harpoons. There were guns. An idea occurred to Chu.

You say we need more patrols. You are definitely not wrong. She let the thought dangle like a rope between them, let Holder grab hold, pull it in. And the Gov won’t give them to us…

Holder eyed her, skeptical at first, then nodding as he tasted the idea. His gaze went back to the Labor boats, and now he smiled. We buy them.

Chu nodded. We buy them.

Grandma’s got chavos?

The one thing she does have.

Gentle precip scoured the shit smell from the air. It dimpled the canal with tiny silver rings. The street preacher, still railing, leveled a finger at Chu. She nodded to him, and smiled. His hand mimed a gun, aimed at her, and he winked: bang!, a moment of connection, as though this ruined city had just offered up in totem its strangest and most beautiful creature.

His sermon didn’t miss a beat.

Chu turned her face up into the rain, and let herself be cleansed.

Two

I Never Regret You

Zola, baby!

The call rang at the center of Zola’s mind. Marco’s touch, urgent, full of need, too long out of the Light. He had the itch. His presence in Zola’s mind drew her forward, her gondola making slow progress up the canal. East 17th Street, a narrow canyon of concrete, dangling vines, the rusty press of anchored scavenger barges. Scrap vendors cried their wares, those last bits of sellable flesh picked from the bones of the old city. “Copper wire, yo! Hammered clean, real pure, no zinc! Take a look, mama!” “Porcelain, porcelain! Granite and marble! Whole tons, ya, barato real! Make me an offer!” Late summer humidity hung thick in the air; everything shimmered.

Zola!

Zola pressed her mind to Marco’s: Be there righteous fast, baby. We need food, ya. Then I’m home. Home. Nowhere, everywhere. Wherever she was together with Marco. Wherever the Light called them.

She leaned hard on the oar, sweating, angling her gondola through a school of two-seater junks—a pack of Moby Jah boys whose faces turned and in unison showed Zola teeth filed into rows of incisors, sharklike and predatory. Their minds reached out for Zola’s—a whisper, a collective unified by mad beats and fierce love for Moby Jah. They sailed around Zola’s gondola, circles and figure eights, each rainbow-painted boat quick and moving in eerie coordination with the others, like the schools of mackerel skimming the concrete foundations below. They were synced. They turned their teeth at Zola and as they slid past, their minds couldn’t quite touch hers and so they spoke aloud.

“Hot hot day, girl, ya. Be hot like you.” Their words hung, an affront to the physical space between them and Zola. “Why your mind so far away, huh? You a junkie, girl? You are, ya. Junkie girl.” Their laughter was the laughter of one, spilling from many, Moby Jah’s laughter. “We take care of you, sweet junkie girl. Take care of you right.” Out loud, their voices cut the air, made Zola’s isolation burn, made her mind feel like a stone cast from a cliff, disconnected, alone. She bared her teeth and hissed at the men, and as she did a tremble worked itself out from somewhere deep in her body. The need to connect. Her hands shook. She fought the urge to vomit.

She had the itch, too.

“Junkie girl, all burned up.” The Moby Jah boys corralled her. She regretted now coming at Stuy Town from the south. But Midtown was rife with thug cops hired by the Gov bitch whose sleek boat had prowled the city for months now, busting up halos. These cops, their sole focus was bagging junkies like Zola. She made to push through the Moby Jah boys, who’d cut her off now, their incisor smiles aimed her way. They toyed with her, steering their little boats at hers then veering away at the last instant—letting her know that if they wanted her, she was theirs. Zola reached into the chest pocket of her overalls, touched the tiny pearl-handled two-shot pistol she kept there. As she did, all the Moby Jah boys, every single one, snapped their heads to an electric barge up the way, crewed by three men and two women.

Cops.

Cops, with their little steel shields pinned to the chests of old Kevlar vests, pinned to the shoulders of torn T-shirts, pinned anywhere they couldn’t be missed, as though the law had come down and baptized them of their sins and justified their natures. They’d all been slavers and thugs before the Gov bitch had come and bestowed badges. Now they were slavers and thugs who believed themselves legit.

Casually, the cops regarded the Moby Jah boys. They all held weapons—an old AK, pistols, a sawed-off. One old man held a simple fishing spear, a panting white bull terrier parked in his lap. The Moby Jah boys scattered, bobbing their heads twice to each stroke of the oar, and disappeared up an alley clogged with floating plastic.

It was just Zola then. She stood there in her gondola. The cops zeroed on her, all five of them. One of the men, a muscled blond who wore his badge pinned to a frayed straw hat, looked her up and down as the cop barge drew close. Zola braced herself to fight.

Zola, baby! Marco’s mind, touching hers. Need you here, girl. Soon, ya.

Busy, baby. Hush.

“Ma’am,” the blond cop said aloud, and touched the brim of his hat like some cowboy of yore as the two boats squeezed past each other in the narrow row between vendor barges. Zola forced herself to smile as gunwales nearly touched. She trembled, as much from fear now as from the itch. One of the cop women, big and scarred—she cocked her head back in contempt and said to the big blond:

“You ain’t no super suave, Benji, you a lawman now. Act it, ya.”

“Just being polite, Captain,” and the blond smiled broadly at Zola. The woman called Captain, who wore old surplus camouflage with brass on the epaulets, and whose shoulders carried the exaggerated swagger of street authority—she pegged Zola with a narrow look.

“You look like someone maybe I know, girl. What’s your name?” The boats, almost past each other now. Zola, still smiling, working the oar, trying to slip away—

The cop captain grabbed the gondola’s gunwale. The woman’s mind reached out, a probing flicker inside Zola’s skull. Zola tried to project her own mind like a shield, press her thoughts to the captain’s, the most natural of connections, a casual sharing of memory, the whispered merger of experience. She was Zola—once the star navigator at Latitude. She’d steered fleets of ships across the globe with her mind, easy as a smile, shared the simultaneous thoughts of ten thousand since her earliest memories. Connection had once been as natural as breathing. She pressed her thoughts forward, desperate now to connect with just one person.

There was nothing. The Light had burned her clean, and the captain knew it. Predatory recognition lit the woman’s eyes.

“Junkie.” She grinned horribly—brown wooden dentures, street-carved by some Rican whittler. “What’s your name, junkie? Your name Zola? Got a friend wants to meet you. You’re all she ever talks about.” Zola, leaning hard on the oar, going nowhere. The captain held the gondola fast. The other cops scrambled, reaching for Zola, reaching for her boat. “Benji, get her,” the captain ordered. Benji stepped across, ungainly, reaching.

Zola reacted—pure muscle memory, a fighting fitness class, part of her Latitude girlhood. Her foot snapped out, a straight kick that caught the big blond cop in the chest. His arms flailed. His eyes went wide. He fell back against the captain, then slid cursing between the two boats and into the canal. Zola brought her heel down on the captain’s hand. The woman recoiled, hatred twisting her face. She lunged, but Zola was already on the gondola’s oar, sliding slo-mo down the canal, just beyond reach, the vendors quiet now, old Carib mamas and Rican ’crete hawkers staring at the junkie girl heaving at the oar and the cops cursing in her wake and trying to get their barge turned around. It was too wide. It wedged itself across the canal. In the water, the blond cop sputtered, holding his hat high where it wouldn’t get wet. The captain shook pain from her hand.

Zola, oaring away, faster now, the cop boat receding. She aimed her middle finger at the cop boat. “Chinga tu madre!”

The captain bared brown wooden teeth. She pulled a big pistol from a holster and brought it level.

“No!” The old man in the back of the cop barge stood, holding his fishing spear in one hand and the little white terrier in the other. “She’s worth more alive.”

“Still worth something dead.”

“We know her now. We’ll find her again.”

Zola felt that pistol aiming for her head, but the shot never came. The captain didn’t pull the trigger. Zola angled the gondola around a corner, a narrow alley, looked back, a last glimpse. The captain, sucking those teeth, her gun dangling at her side. The old man and the dog both looking Zola’s way—the old man smiled at her.

* * *

Zola, baby! Marco, insistent now, full of possession and love and heat and fear. His thoughts reaching out like fingertips to touch Zola. For an instant they connected, a fluid rush of union, the way Zola used to do before the Light had burned the ability out of her. Now it only ever happened with Marco, a few days each time after they’d touched the Light together. You good? Are you good?

Ya. She wasn’t caught, but maybe good was saying too much. There had been a time, before the Light, before Marco, when her life had been easy. Those memories, days in Latitude when she’d done what she’d been born to do—navigator, lover, collector of far-flung artifacts—it was as though that life had belonged to someone else. Now, with cops not far behind and Zola winding the gondola through random streets, trying to lose herself down alleys and blend into the press of boat traffic, she couldn’t remember what it felt like to be something other than hunted. She worked the oar back and forth, let the air breathe against her sweat. I’m good, she told Marco, and then: Baby, they know my name.

Just a matter of time. But you’re safe?

Safe.

Marco’s relief flooded Zola. His mind braided through hers. Zola peered through his eyes—down the face of the Stuy tower from whose ruin he leaned, dangling from the dark cavity of an empty window, a vine clenched in one fist. Sunlight blazed off the East River far below, searing white light around which the city seemed insubstantial, a bardo of gray Stuy Town monoliths rising out of the spiraling foam of tidal vortices. Concrete and brine, a world of physical truths from which Zola felt Marco’s mind recoil, the confines of what Jacirai called the mortal cage. Marco’s thoughts bent wildly away from the moment, wrapped themselves instead around Zola’s mind, zeroing playfully on the things he wanted to do to her—half fantasy, half memory. His lips on her neck, the gentle tug of his teeth on her nipples, the places his tongue would tease. But beneath those urges was a different, more desperate desire, a wish to be back among the folds of the Light, enveloped in a sea of thoughts so deep they’d never find the limits.

Into the Light… The whisper of a thought, unbidden, and Marco leaned far out the window, into blinding sun. Zola felt his fear, his urge to let go. Don’t make me wait, girl.

He had the itch, bad.

Be easy, baby. Cops filling the day thick as mosquitoes. But I’m coming, ya. Soon now. Zola’s shoulders flexed against the oar; she fought the shake in her hands. Real soon, baby.

She worked the gondola through the boat traffic—the scavenger barges loaded down with rebar, ’crete dust, and steel girders stripped from uptown scrapers and towed by Rican men in longboats, oars like centipede legs sculling the canal; the schools of rainbow junks, men shirtless in the heat, on the prowl for a hustle, their shaved heads dark and nodding in unison to the beats of Moby Jah; black market banker types who rode in the posh leather seats of gleaming polymer-hulled boats, their collars buttoned priest-high and bound by silk cravats, faces vacant, meditative: their minds riding the ebb and flow of currency from one black account to another.

Through the traffic, back onto East 17th now, a wide deep pool at the intersection of First Ave. Old Rican mommas had set up shop there, rafting square garden barges together in the afternoon sun. They sat, wrapped in the personal shade of thin shawls, behind tables stacked with jars of herbs and spice seeds. From behind giant aviator shades, they watched as East Siders browsed their garden rows.

Zola scanned the avenue for cops, and saw none. She felt exposed: this was a place where normal people shopped—as normal as people in this city got. These new cops, they gave rewards for junkies. But junkies had needs too. Marco had needs.

Zola steeled herself, thrust her chin defiantly forward, and threw a line. She stepped out into a bed of root vegetables. This she wandered slowly, probing bare toes into black topsoil disturbed by a thousand shoppers before her—skinny carrots, onions whose impressive stalks belied bulbs no bigger than her thumb. The tomatoes, however, were real beauties. They hung pendulous, oxhearts nearly too heavy for their vines, on the yellow side, not quite ripe. Perfect. Bending low, Zola reached out to touch one. In the corner of her mind, she felt the pressure of Marco’s need, his itch. It made her hand shake.

“¿Puedo ayudarte, hija?” A Rican woman stepped toward her. In her insectoid shades, the distorted reflection of Zola’s gaunt face. Zola picked two tomatoes and held them up.

“This. Saw palmetto, too. And mullein. I need it dry, madre. Dry enough to burn, ya.”

The Rican woman said nothing. With a finger she pushed the shades up over her brow—her black eyes fixed on the tomatoes, clocked the tremor in Zola’s hand. A stillness came over her and she stood like that, poised, hand raised in mid-gesture, occupied by the sort of silence that meant her mind had merged with others from her collective. For a beat, it was like time stopping, then the madre’s eyes refocused on Zola. Her expression was hard.

“East Side Growers don’t want no junkies in our gardens. You got to go, honey.” She glanced pointedly down the row, where a young, East Side mother leaned over, inspecting a patch of leeks. A clean skirt and hair pulled back and rings on her fingers, the moneyed ease of someone who had never seen bad shit—or, Zola figured, the Burning Light of Truth. Beside the woman sat a toddler in denim overalls, the miniature, clean version of what Zola wore. Desirable customers. The Rican woman waved a hand as though Zola were a fly to be shooed. “You got to go!”

“Junkies got to eat, too, madre.” Zola held up the tomatoes. “Already picked them, ya. Got to buy them now.”

The madre eyed Zola for another hard beat. Then, sucking her lip, she jerked her head forward, dropping the shades to her nose. She aimed a finger at the ground, as though some immutable principle lay etched there in the garden’s topsoil.

“Chavos,” she stated.

“Si, si.” Zola clutched the front of her overalls and shook them. Coins jingled in the bib pocket.

“No. Chavos real.” The madre raised an index finger to her temple. She went still again, and this time Zola felt the whisper of the woman’s mind reaching out, to Zola this time, trying to connect, the way the cop woman’s had—but in Zola’s lobes, atrophied by the breadths and depths to which the Light had taken her, it was almost intangible, as impossible to touch as smoke. When she’d come to the old city from Latitude, Zola had still been able to connect. She could’ve reached out and joined the madre, traded real currency. The Light, though, took its tithe. After three trips with Marco and the others, it was hard to connect. After ten, Zola could only connect in the calm days that followed each trip. After twenty, her hands had begun to shake and her dreams had turned to white fire, and now she couldn’t join anyone anymore, except for Marco. Jacirai said it might come back if she stopped, but Zola doubted it. It was a sacrifice they all made, those who wanted to touch the Light. Sometimes it seemed too much.

“Real is real, ya.” Zola shook the coins again. “I pay, madre, you sell.”

The shakes set in again, deep in Zola’s chest, emanating out to her limbs. The itch, the need to connect.

Out on the canal, the cop boat appeared, sailing east now. Under her breath, Zola cursed. She turned away from the cops, held a hand to her brow to obscure her face. The Rican woman watched, her gaze switching from Zola to the cops and back, clocking the whole thing. She pursed her lips, considering.

“Please, madre,” Zola pleaded. “I see it in your face you think I got no life worth living, ya. But I got love, and someone to live for, someone who loves me. Those puto slave cops take me,” a glance toward the cop boat, “and that’s all gone. I’ll be gone. Please.” The madre frowned, not without sympathy.

“You take them.” Indicating the tomatoes. “You take them and you go.”

Heat worked its way up Zola’s spine. Marco’s mind, itching bad.

Zola, baby… Leaning far out into the light, yearning to let go. Zola stepped closer to the Rican woman.

“And saw palmetto,” she insisted. “Mullein, too. I need it real dry, ya. Dry enough to burn.” Her whole body afire with the itch, her reflection twisting in the woman’s shades. “Thank you, madre.”

* * *

“You got to be careful, baby.” Marco, framed in pale light at the open edge of the thirty-fifth floor, where once had been floor-to-ceiling windows and now hung a thick screen of vines. He sat naked, arms wrapped around his knees, the immediacy of his voice a source of grounding warmth in the building’s gutted solitude. “That defiance of yours get you killed, ya.” He meant the cops. He’d been there with Zola, watching through her eyes, listening through her ears. He’d seen the woman cop raise her pistol.

“It’s okay,” Zola told him. She’d built a small driftwood fire on bare concrete near the edge where its smoke would leak out into the day, and now cut tomatoes into palm-thick slices with the same folding knife she used for cleaning fish. It was an old residential building. Rican and Carib scavs had stripped it long ago, like most of the old city core, mined it for raw materials for the new cities up north along the Hudson. Nothing remained now but concrete struts, spines of rebar—Stuy Town a Venetian ruin rising from the river far below.

Marco had tried to make good on his promises, had come on determined and rough, kissing, groping. But he had the itch bad and couldn’t get it up. After, they had lain there in cavernous isolation, wrapped in the coarse folds of an ancient army surplus blanket. Zola had tried to hold him.

“Lo siento, baby,” he’d said, and turned away.

She’d run her fingertips over the tattoos on his shoulders and along his arms, images he’d designed himself, a narrative tapestry of his short life, all the places he’d ever been, inked into his skin. A painted kabuki mask on his shoulder, emblemizing his time in a Tokyo farming arcology. A spiraling, fanged snake he’d had done in a Sao Paolo art collective. An AK over his heart, from Mexico City. The two of them had connected in the Light, gone deep into each other’s memories. He was rough and uneducated, at least in the ways Zola was educated, but the breadth of his experience made her feel small, and she liked that. He’d been everywhere. He’d sought vivid experiences, his true north the ardent belief in a life wholly lived, equating meaning to the most raw sensations. He hungered to find the limits of his being. It was only natural he would come to the Burning Light.

During the cool nights between the ritual halos when the itch kept them from sleeping, Zola would lay an index finger against his skin, and in the low firelight whatever image she touched, Marco would tell that story—not like people did now, but with words, spinning a tale like people used to do. Zola would recall his memory, a memory now her own. She loved these stories, these memories he’d given her—always exotic, far-flung, full of fighting and broken, drunken hearts. With each one a piece of Marco would fall into place, some historical marker helping to map him; his smile, his dark moods, each shared memory a stepping stone, bringing him closer to Zola.

There in the cavernous twilight of the empty Stuy tower, they lay together in strained silence. His failure frightened them. It marked his decline.

“We should go somewhere,” Zola’d said into the growing darkness. “Make a new tattoo.”

For a long while, they both simply breathed, relishing that sweet lie.

“All times are now, ya,” Marco said finally, maybe to Zola or maybe only to himself, and then he’d slipped from under the blanket and away from her. All times are now. It was a meaningless phrase to Zola, the sort of thing Jacirai would declare in one of his mad sermons between rituals, the Burning Lighters stationed in a sphere around him in whatever vacant tower they squatted. His eyes would roll back so only the whites were visible and he would growl and spit and give utterance like some feral demon—from on high, ya, the echoes of things they’d all touched in the Light. His sermons, sometimes they spoke straight to the heart of truth—that in the Light they all became something more, godlike in the depth of their union—and sometimes it seemed all nonsense, just noise to keep everyone going, feeling connected until the next ritual, the next sweet burn.

As Zola covered the tomato slices in an herb mixture—thyme, basil, sea salt, and white pepper, which she took in pinches from a small leather pouch—she watched Marco. He looked small, boyish. Ribs etched his back, and he trembled. It was as though the Light had hollowed him, as though he were receding in stages from his own flesh so that others might touch the truth. Thus was his lot, a medium for the Light. Zola strained to touch her mind to his, and for a moment they reveled in closeness.

You give so much.

She set the tomatoes to fry in a small pan on the fire, turning them every so often with the tip of her knife. The sun had half set and turned the water below the color of blood. Zola figured there was something natural in this space, in moments like this, something primitive and true. Wrapped in the blanket, she imagined herself like the Anasazi, staring out at the desert from the high safety of their hollow cliffs. She’d had a collection of Anasazi relics once, in a special plexi case in her Latitude abode. Pot shards with zigzag designs, a stone grinding tool. Prizes in her collection of souvenirs from all over the globe, talismans to the idea of a world growing smaller, coming together, like it had been when the old cities had been filled with people instead of water—but now that was all gone. The sun turned red over the canals and flooded brownstones, a different sort of desert. Down there, the cops hunted junkies. And those cops knew Zola’s name.

“Baby. Eat.” She held the pan and beckoned Marco to the fire. He smiled weakly.

“Lo siento, baby, I just got no appetite. Looks mad tasty, ya, but…” He dropped his face into his hands and squeezed his forehead. “My head, killing me fucking bad.”

The Rican madre had given Zola the mullein and saw palmetto wrapped in two big banana leaves, and these Zola pulled from the pocket of her discarded overalls. She mixed the herbs together with some local rooftop dirt weed and tobacco from a stale cigarette, both of which she’d kept hidden in a little wooden box in her day bag. She rolled it all together in a tear of notebook paper and licked it shut.

“You ever regret it?” Marco asked, his face still cradled in his palms. Zola leaned close into the fire to light the joint. Marco looked at her. “Do you?” His face hollow, an apparition of who he’d once been. A stab of fear shot through Zola: Marco was fading, and they both knew it. Zola understood exactly what he was asking. Did she regret losing that other life? Was the Light worth the sacrifice? Was he worth it?

That other life. Even the memory of it felt somehow false, a life so wholly different it might never have been.

* * *

Her navigator’s abode. A slice of sky wrapped in photosensitive plexi, the sunlight pouring in. This was what Zola remembered. Resting in the deep folds of an African leather sofa, bathing in sunlight as she did the work for which she was born. Navigating. Reaching out to her ships, their eager minds meeting hers as they cut across some far-flung stretch of globe. Around Zola, her collection of artifacts. Zulu spears and Siberian oak tables, pottery shards and computer keyboards, ornamental wristwatches and Amazonian fertility totems, all arranged geographically, a ritual layout of lost histories. Curled up at her feet, two great and friendly wolfhounds.

Her ships, sunlight in the mornings. Latitude filling her mind, that easy hive hum. Six thousand people living their lives, their minds shared with hers. The sensate minutiae of their mornings, breakfast smells and first-light trysts, people doing Latitude’s work. The hum, a greater metabolism in which Zola had always been immersed, whose unifying thread was a collective will bent on the flow of goods, the accumulation and reinvestment of boggling amounts of currency. Connection. This was what she remembered.

And Byron. His dense physicality, the gentle way his mind braided through hers. Her primary, her mate. Born the same day, the two of them. Brought forth from the laboratory wombs deep in the Latitude vaults. Connection—this was what they were designed for. Brought forth together, the two of them, already immersed in the buzz of Latitude’s collective ebb and flow. The cinnamon and musk smell of him, his eyes lighting up when it was impossible to tell whose thought belonged to whom, his thick arm splayed possessively across her in sleep. Born together, born for each other.

She knew now that the Light had touched her first in dreams. Now she could recognize it. Half-remembered images, how she’d start awake, and the aftereffects, a manic residue she carried through her days. In sleep, the Light came to her as quick, stabbing visions. The ocean’s slate horizon—out there, beyond the globe’s long curve, a flash, brighter than the sun. Pure white light.

She’d wake next to Byron in a sweating tangle of Milanese silk, the morning sun slashing horizontally across the apartment, the dream already fading. Beside her, Byron would sleep on, the bulk of him rising and falling with meaty breaths, gentle and oblivious, his dreams the dreams of Latitude. A flash. That was all it had been, just a dream.

But then the Light came to her when she was awake.

Her abode was on the thirteenth floor of Latitude’s North River Tower, a diamond of steel and plexi that rose like a rapier tip from the bank of the Hudson. A monument to the rebirth of global trade. Latitude, reaching out, touching every part of the world, making it smaller every year. One day, it would be the way it had been centuries before, cheap goods from across the world filling everyone’s life. This was Latitude’s directive, and it was therefore Zola’s. Deep in the nest of an African leather sofa, she worked with her face turned up to the morning sun.

Four thousand miles away, a fleet of ten catties sailed in formation, parallel to a thin white ribbon of sand just visible against the eastern horizon. These were her ships, a day out of Ivory Coast, loaded up with industrial diamonds, copper, manganese, gunning for the North Atlantic. Their sails dug hard into wind blown from a storm to the south. Their minds pressed Zola’s, full of the joy of their sprint.

She ran them north, and as she did Byron emerged naked from sleep and came to her, rubbing sleep from his soft moon face. Zola pulled him down and straddled him, and rode him in the sofa’s smooth leather as the sun warmed them both. She let the ships feel him, let him feel the ships and salt air and motion. Together they watched the prows slice long swells into rainbows of silver spray. They felt the waves, their endless roll perfectly in tune with Zola’s movements. In the freedom of it he laughed and bit Zola’s neck, and through it all Latitude was there, in the background, encouraging, other minds reaching out, joining them in the moment. Light filled the abode and the white orb of the sun seemed to grow around them, and somehow inside Zola, too, a hot coin at the top of her spine, spreading, like she was falling into it—

I AM.

The statement blotted out everything. It wasn’t a voice, or even thought. It was simply knowledge.

I AM.

Some axis tilted inside Zola, gravity changed direction. The dream returned to her. That lighthouse flash. Now there were people on a shoreline—they stared at the horizon. They had been there for a long time, she sensed, watching. All at once they turned. Fire filled their eyes.

I KNOW YOU.

It was her face. All of them, they were her.

YOU ARE.

White light seared the horizon. It grew, a star exploding, an infant taking its first breath. It enveloped the sea, the shoreline, the people. White fire, a magnesium flare, the hot spot in her head exploding, filling her, and everything else was gone.

When the Light receded, Zola didn’t know how much time had passed. There on the couch, blinking, still atop Byron; her heart hammered in her ears. Her mind reached out to her ships. They were disconcerted, still running north, but slow now, their formation faltering. Byron, one hand frozen against her breast, gaped at Zola.

“I am… ,” he said after a moment, “amazing.”

“Did you… ?” Zola, struggling to reel in her ships, didn’t know what to say. Did you see… ?

You shone like the SUN, girl.

No. The light. Come on, did you see it?

Byron, grinning… I saw.

* * *

High up in the dead Stuy tower, Zola stared into the fire and exhaled smoke. “Sometimes I regret, ya.” Honest, because she always was with Marco. “I miss my ships.”

The itch came on strong and for a moment it made Zola shudder under her blanket. Some days, like today, when it had been a long time between ceremonies, it felt as though her soul had been stretched between two far-away moments in time. It felt like it might snap. Her mind railed against its isolation.

“I regret it bad, sometimes. Wish I could unsee everything the Light shown me. Just wake up one morning back in Latitude, my people all around, and me linked with my fleet of big catties. Sailing down the North Sea, steering them home. I miss my people.” The white noise press of Latitude’s minds, gentle as low surf breaking. All of them dead now, all of it gone. She said, “Latitude collected our memories. I never knew anything but that, like time just washed through us and collected in a pool. Never lost. Now it’s like it never happened.” Outside, the city had gone red as the sun bled away. “I lose every moment, like I’m not even here, ya. The time’s just gone, no proof I ever witnessed it.”

“The Light reach out to you long before I ever met you,” Marco said. With his feet at the edge of the drop, he shivered. “You a medium, same as me. Why that Gov lady got such a thing for you—she knows it.” He looked at Zola. “When I’m gone, you got to step in, answer the call.”

“Don’t talk like that. You going nowhere.” Zola rose from the fire and moved to Marco. She sat behind him, wrapped herself and the blanket around him, meeting as much of his skin with hers as she could. He was cold. “This’ll help your head, baby.” Motherly, she wedged the joint between his lips.

He sucked deep. As he held the smoke in his lungs Zola could feel his heart stutter against her breast. His tremble eased then, and Zola pressed her lips to his back, to his neck, to his shoulder. Her mind reached out for his, but she didn’t have enough left, and neither did he. They both needed to touch the Light. From within the isolation of her own skull, she whispered in his ear:

“I never regret you.”

Excerpted from The Burning Light © Bradley Beaulieu and Rob Ziegler, 2016