Eight, sir; seven, sir;

Six, sir; five, sir;

Four, sir; three, sir;

Two, sir; one!

Tenser, said the Tensor.

Tenser, said the Tensor.

Tension, apprehension,

And dissension have begun.

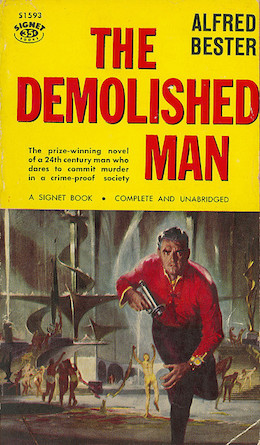

With the Hugo winners recently announced for 2016, it’s the perfect time to look back to the novel that was awarded the first ever Hugo Award. That novel was The Demolished Man, a book that stands with The Stars My Destination as one of the two masterpieces of SF author Alfred Bester.

The past, as the saying goes, is a foreign country, and visiting it again often leads to unpleasant surprises. Though the novel was awarded the then-highest honor in Science Fiction, how does The Demolished Man hold up for readers today? Can it still be read and enjoyed by people who aren’t seeking a deep dive into the history of the field, but want to enjoy an early and important work? Is it even readable by contemporary audiences? Should you read it?

The Demolished Man presents us with a science fictional future world that is quintessentially a product of its 1950s origins. There are computers, powerful even by the standards of today—although their punchcard format might incite giggles in readers rather than awe. It is a world of Mad Men or North by Northwest-like captains of industry: technicolor, confident characters that are, yes, primarily white male Americans, striding forward into the future. It is a rapacious extrapolation of trends of that Mad Men world in many of the same ways that C.L Kornbluth and Frederik Pohl’s The Space Merchants is, although that novel takes that trend even further than The Demolished Man does. Discussion of that novel merits its own space and time.

What drives the story of The Demolished Man, however, beyond its world reminiscent of Mad Men or the massive and powerful punchcard computers, are telepaths. Telepaths and their psionic abilities are not new in science fiction now and they weren’t when Bester wrote The Demolished Man, either. Such powers and abilities date back to at least A.E. van Vogt, E.E. “Doc” Smith, and John W. Campbell more than a decade before the novel, if not earlier. The innovation and the invention that Bester brings to the concept, however, is to broaden and explore the sociological elements and implications. We don’t just have a superior human psionic running for his life like Jommy Cross of Slan. Here we have telepaths existing as an integral part of society, with a society interior to themselves and exterior to the world. How would the world work if a stratum of society could read minds? What are the implications of that? Bester gives us the answers.

The plotting of the novel itself starts us off with the story of Ben Reich, the aforementioned captain of industry, seemingly on top of the world—a New Yorker at home in New York, the center of this world. Alfred Bester was a native New Yorker, and I, as an expat of New York City, note and approve how much of a New York-centric world that the book has. We have scenes outside of the city, even in space, but they all feel secondary and not important, echoing the spirit of that famous New Yorker magazine cover. New York is the center, and it’s the center that is important and our protagonist knows it. But all is not well in Reich’s world, and he knows that too. Trouble is approaching, his position and power are under threat. But what to do? And how to do it? The unthinkable must be considered: Murder. And in contemplating the crime, complicated methods must be constructed to assure that he can get away with that crime. But how does one outwit Justice computers and the ever-present telepaths? The first half of the novel, in introducing this world, builds up Reich’s plan like a carefully composed painting, the pieces coming together as we move toward the actual incident. The pace is whip fast by modern standards (although a reader of, say, van Vogt, might consider the pacing sedate), bringing us toward the fulcrum of the novel before a reader even knows it.

The Demolished Man then shifts, after the murder, primarily to Lincoln Powell, an Esper detective. Although we’ve met Espers earlier in the novel, in this second half, we get to see the Espers from the inside, in the context of trying to solve the mystery and prove that Reich was indeed responsible. The cat and mouse game switches in terms of the crime itself, as we watch Powell trying to tease out the puzzle. The symmetry between the buildup to the crime, and then the process of solving the crime after it takes place is now a standard fusion form. This science fiction/mystery fusion works extremely well, and it may surprise readers to know that The Demolished Man is actually one of the early examples of that fusion of genres. Many science fiction authors who seek to mix mystery into their science fiction could profit by observing how Bester does it in this novel. Characters as contemporary as the Expanse Series’ detective Joe Miller owe some of their DNA to this book.

But in the breathless, rapid-fire plotting of the novel, we get so much more than just a mystery and all of it is lean, mean, and compactly written. Bester gives us a real sense of the telepaths and what they are about—a guild of people with honor and responsibilities, whose exiled members keenly feel the loss of being cut off from that former union. And yet, the telepaths are a secret society, willing to try and breed ever more powerful and numerous telepaths, toward the goal of populating the world entirely with telepaths. They see themselves as the future, and are playing a long game to make that happen.

One interesting aspect of the novel is its distinctive typography, which is best experienced in print rather than (or in addition to) listening to it as an audiobook or even an ebook. The use of fonts, and spacing, in the text, and even the depiction of some character names are a reflection of the characters and ideas as they are shortened and altered through the clever use of type. This is meant to help convey the shorthand of the telepaths in depicting how they think of people and people’s names: “Weyg&” for Weygand, “@kins” for Atkins, and so forth. A defrocked telepath whom Reich engages for his murder scheme has his title and rank listed as “Esper 2“. A denial of wanting snow in a mental conversation between telepaths is rendered as “s n o w“. This is all rendered poorly in ebook form, and is completely lost in audiobook, of course, which dilutes the impact of what Bester was trying to achieve in demonstrating how Espers think differently by showing it on the page. He does accomplish this in more conventional ways, of course, but it’s in the typography that this difference is most directly conveyed.

Fans of the science fiction series Babylon 5 will know that the show features telepaths as part of its future setting, and delves in the the details of how telepaths would interact with the rest of society as well as their internal dynamics. The series makes sense of what it means to have telepaths as a known entity in the world, very much in the tradition of The Demolished Man. And it is clear that the creator of the series, J. Michael Straczynski, deliberately took more than a few cues from the novel: one of the recurring minor characters in the series is an enforcement officer of the telepaths, a Psi Cop, played by Walter Koenig. He is powerful, intelligent, ruthless, and devoted to telepaths and their goals. The name of that cop? Alfred Bester. It is a deliberate and fine tribute to the author, and to this book.

There is much more to be found in the book, from its exploration of Freudian psychology to some extremely strange, but hauntingly irresistible, character dynamics at play. The novel is one of those that bears repeat reading to catch the subtleties of character and nuance, relationships and worldbuilding, that cannot be picked up on the first run-through. And there are surprises, especially in the denouement, that I hesitate to spoil for first time readers…instead, I’ll simply state my contention that The Demolished Man remains as relevant and interesting to readers and writers today as it was in the 1950s.

An ex-pat New Yorker living in Minnesota, Paul Weimer has been reading sci-fi and fantasy for over 30 years. An avid and enthusiastic amateur photographer, blogger and podcaster, Paul primarily contributes to the Skiffy and Fanty Show as blogger and podcaster, and the SFF Audio podcast. If you’ve spent any time reading about SFF online, you’ve probably read one of his blog comments or tweets (he’s @PrinceJvstin).