Roger Zelazny’s biographer and friend, Ted Krulik, is sharing insights and anecdotes from the author.

Roger was open to ANYTHING. Those friends who saw him in role-playing games could tell you that he was a master at improvising fresh characters out of the air. If someone he trusted made a suggestion that appealed to him, Roger would run with it.

When I hosted a one-on-one interview with Roger in front of a packed room at Lunacon in 1989, I made my introduction in this way: “We’re here to speak to a person who purports to be a late twentieth-century American science fiction writer on the shadow Earth. Who are you really?”

Roger picked up the microphone and told the audience: “Seymour Jist, a retired croupier from Akron, Ohio. Roger Zelazny hired me to stand in for him in cases such as these because he’s a very reclusive individual. I met him in Cleveland about ten years ago. I lost a bet to him and I’ve been paying him back ever since.”

His response was completely off-the-cuff; but with that handful of sentences, Roger created a person who lived in the audience’s mind with a job and a history and a reason for being.

I wanted to hear more about Seymour Jist and his connection to Roger Zelazny. As far as I know, this was his only mention of the character anywhere. Unless one of you, out there, had heard Roger speak further of Seymour Jist…

The Emergence of Lord of Light

The source of one of Roger’s greatest single works of fiction came about in the most mundane way. A very minor incident enabled him to open up his imagination to possibilities and, with that, he developed a fascinating other world and a singular character named Mahasamatman, who preferred to be called Sam.

Let Roger explain:

I got the idea for my novel Lord of Light when I cut myself shaving just before I was to go on a panel at a convention. I had to go out there with this big gash in my face. I remember that I thought: I wish I could change bodies. That started a train of thought: If one could change bodies, what sort of cultural background would that fit into? Something like transmigration or reincarnation—that would fit into religion. Seemed like Buddhist. What kind of story would I get out of that?

The idea stuck while I was sitting on the panel. I did a quick mental search: It seemed a lot of fantasy novels I’ve seen used Norse mythology and Irish and Greek but I hadn’t seen anything using Hindu mythology. And there was an interesting conflict there in that Buddha himself used his religion in an attempt to reform the older religions that came before him. In that sense, it was a political thing.

I read Herman Hesse’s Siddhartha while I was writing Lord of Light along with many other things. It seemed a good time to read it so I could see what he had to say about Buddha. In my first chapter I was thinking in terms of the big battle scene in the Mahabarata. It helped me in visualizing the battle in my novel.

Each of the chapters in the novel is almost an independent story. In fact, several were sold as novelettes. Ed Ferman bought one for Fantasy & Science Fiction called “Death and the Executioner.” That story got this whole thing going.

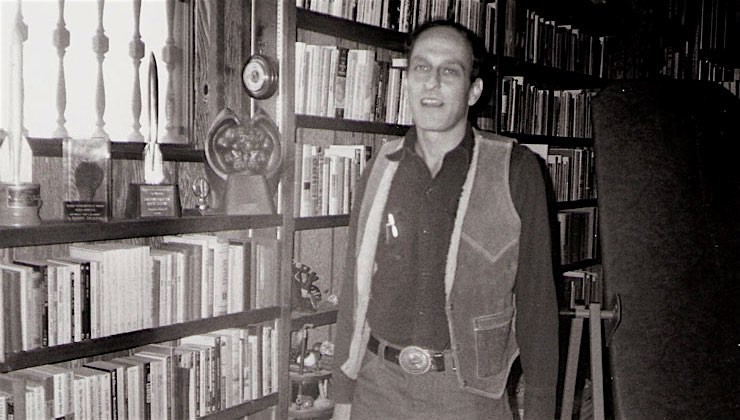

This, and the following observations by Roger, took place during the first week of November, 1982, when he invited me to interview him in his home in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

Where the Immortal Figure Comes From

I asked Roger about the continuing fascination he had for revisiting an immortal protagonist in so many of his works. Where did that concept come from? It was a simple question, one that anyone would have asked.

He jumped to his feet with a loud exclamation. “I can tell you where the immortal figure comes from,” he said.

He walked away from my cassette tape recorder and began hunting through his bookshelves. He found what he was looking for, excitement in his eyes, and handed me an old hard-covered book. Avidly pointing to the book, he explained:

Are you familiar with the trilogy of books by George Sylvester Viereck and Paul Eldridge? Possibly the first books I’ve ever read about an immortal character.

That book you have in your hand was the first one, My First Two Thousand Years: The Autobiography of the Wandering Jew. It was published in 1928. The Wandering Jew tells his story during World War One. He is with a group of people trapped on Mount Athos for six months. There is a psychoanalyst there and one man—the protagonist—agrees to go under psychoanalysis in an experiment. That man turns out to be the one man in the world with a memory that goes back two thousand years. He tells his life throughout history from the time of Jesus through the Middle Ages and into the twentieth century.

Viereck died some time ago, but Eldredge died on July 26 of this year [1982] at the age of ninety-four.

The following books that Viereck and Eldredge wrote tell the same story from the points of view of two other immortals that the Wandering Jew had met in the first book. In his telling, the Wandering Jew continues to meet this strange woman throughout history. She turns out to be Salome who received a curse from John the Baptist when she caused him to lose his head. The authors tell her story in the second book, Salome: The Wandering Jewess: My First Two Thousand Years of Love.

The third and final book, The Invincible Adam, is told from the point-of-view of a very strange servant the Wandering Jew had met in Africa. Although the servant speaks fluently to other people in the book, he only says one word to the Wandering Jew—‘Catafa’—God. The Wandering Jew is baffled by this servant who won’t speak anything more to him.

This servant is also immortal and tremendously strong. In this last book, we learn his story as he goes through the same historical times as the Wandering Jew.

You may recognize some of the characteristics of these people in my novel This Immortal, in the form of Conrad Nomikos and Hasan the Assassin.

By the way, Ted, that’s an extra copy of My First Two Thousand Years. If you like, you may keep it.

The Source for Eileen Shallot in “He Who Shapes”

In his novella “He Who Shapes,” Roger created a darkly passionate antagonist to stand against his main character, Dr. Charles Render. Eileen Shallot was equal to Render in spite of a severe handicap. That distinction in her character made her all the more intriguing to readers. It seemed natural to me to ask how he had come up with Eileen. When he addressed the question, his brows drew together in concentration. It was a unique moment, a moment when Roger’s eyes lit up with self-discovery. He was moved to say, “No one ever asked me that before.” This is what he told me:

Up until 1964, “He Who Shapes” was the longest piece I had written. I had this background in psychology [from Case Western in Cleveland] so I figured I might as well use it. The story itself deals with a figure reminiscent of a classical tragedy. My actual use of Jungian archetypes is not a conscious thing. That’s just something that emerges. The only place where I consciously use psychological theories in Dream Master [the extended novel version of “He Who Shapes”] overtly is in the psychological discussions between characters.

I can tell you where the character of Eileen Shallot came from. No one ever asked me that before. I was writing “He Who Shapes” when I was working for the Social Security Administration in Baltimore. I received a telephone call concerning a disability claim. I had not taken the application but it was supposed to be my case because we used an alphabetical breakdown to be given assignments. I talked to a woman on the telephone at the time that I was working on the story. I had already started it and had not yet come up with Eileen Shallot.

Talking to this woman on the phone about the case—I couldn’t tell anything was wrong with her. There was nothing in her conversation to indicate that there was anything wrong. We were coming to the end of our conversation and I said, “Hope we’ll get a chance to see each other.” That’s when she told me she was blind. After I hung up, I thought: That’s it. The character of Eileen has to be blind!

All sorts of things about that character’s motives started falling into place. That helped me shape the major plot point that Eileen was obsessed with controlling her environment. The tragic aspect at the end depended on her obsession with Render and her need to manipulate him.

The Hemingway Device

Roger was known for experimenting in various writing techniques. It was ingrained in him to practice the literary styles that the great writers in the mainstream used. He was integral to the movement of a newer generation of writers coming out of the 1960s, a period dubbed “The New Wave,” who deliberately attempted to include the literary devices that had historically belonged to mainstream literature.

In our 1982 interview, Roger expressed his fondness for Hemingway’s writing and a willingness to emulate him:

Ernest Hemingway would write and see the whole story, and then he would intentionally remove something, rewriting the story without it. In his mind, that thing would still be there. Even though the reader doesn’t know what it is, it would influence everything else in the story. The reader would feel there was something there even though he couldn’t put his finger on it.

I do that in what I write. In any novel I write, I have in my mind several things which happened in the protagonist’s past which I never mention in the book. In “A Rose for Ecclesiastes,” I didn’t tell the reader that Gallinger’s first name is Michael. I saw him as a whole person so I had no reason for using his first name. As I told his story, I only showed a part of him; that part that was necessary to the action. I knew the cause of his antagonism for Emory, the father figure in the story, but I saw no reason to go into it. By not stating everything I knew about Gallinger, it made him more real.

In the spring of 1982, I went to the University of Syracuse to study the letters, original manuscripts, and other documents in their library’s Zelazny collection. I accidentally discovered that Roger had hidden in his papers a secret about his writing that he kept from all of us. It’s there in the university library even now—and you can find it if you know where to look. I’ll tell you.

I was reading the text of the short story “Party Set,” the original title of Roger’s “The Graveyard Heart.” Turning the manuscript pages, I came across something totally unexpected. On the back of page 38 of the manuscript was a bold statement, typed all in capital letters, that Roger had copied from another famous author—and I have come to believe Roger strove to follow this as a personal credo all of his writing life:

THERE IS NO USE WRITING ANYTHING

THAT HAS BEEN WRITTEN BEFORE

UNLESS YOU CAN BEAT IT.

WHAT A WRITER IN OUR TIME HAS TO

DO IS WRITE WHAT HASN’T BEEN

WRITTEN BEFORE OR BEAT DEAD MEN

AT WHAT THEY HAVE DONE.

—ERNEST HEMINGWAY, 1936

Theodore Krulik’s encyclopedia of Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels, The Complete Amber Sourcebook, published in 1996 by Avon Books, is still the most exhaustive reference book on that revered series. Through his literary biography Roger Zelazny, published by Frederick Ungar Inc. in 1986, Krulik made accessible to the enthusiast the famed author’s personal concerns. For the first time, aficionados discovered the sources in Zelazny’s own life that inspired his writing. Other literary work includes essays on Richard Matheson in Critical Encounters II for Ungar, edited by Tom Staicar, and on James Gunn’s The Immortals in Death and the Serpent for Greenwood Press, edited by Carl Yoke and Donald Hassler. As a member of the Science Fiction Research Association, Krulik wrote a regular column for their newsletter in the 1980s and 90s entitled “The Shape of Films To Come.” Currently, he is writing a novel about a science fiction writer who gains remarkable powers to see into the minds of others. Krulik hopes to complete World Shaper by the end of 2017.

Theodore Krulik’s encyclopedia of Roger Zelazny’s Amber novels, The Complete Amber Sourcebook, published in 1996 by Avon Books, is still the most exhaustive reference book on that revered series. Through his literary biography Roger Zelazny, published by Frederick Ungar Inc. in 1986, Krulik made accessible to the enthusiast the famed author’s personal concerns. For the first time, aficionados discovered the sources in Zelazny’s own life that inspired his writing. Other literary work includes essays on Richard Matheson in Critical Encounters II for Ungar, edited by Tom Staicar, and on James Gunn’s The Immortals in Death and the Serpent for Greenwood Press, edited by Carl Yoke and Donald Hassler. As a member of the Science Fiction Research Association, Krulik wrote a regular column for their newsletter in the 1980s and 90s entitled “The Shape of Films To Come.” Currently, he is writing a novel about a science fiction writer who gains remarkable powers to see into the minds of others. Krulik hopes to complete World Shaper by the end of 2017.