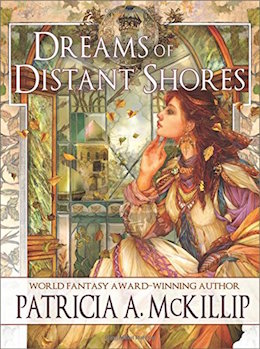

Bestselling author Patricia A. McKillip (The Riddle-Master of Hed, Harpist in the Wind, and The Sorceress and the Cygnet, among others) is one of the most lyrical writers gracing the fantasy genre. Her latest short fiction collection, Dreams of Distant Shores, is a true ode to her many talents. Within these pages you will find a youthful artist possessed by both his painting and his muse, and seductive travelers from the sea enrapturing distant lovers; the statue of a mermaid comes suddenly to life, and two friends are transfixed by a haunted estate.

Fans of McKillip’s ethereal fiction will find much to delight them; those lucky enough to be discovering her work will find much to enchant them. Featuring three brand-new stories and an original introduction by Peter S. Beagle, McKillip’s Dreams of Distant Shores is available June 14th from Tachyon Publications. Below, read an excerpt from “Mer,” one of the new stories in the collection.

Mer

The witch had hitched a ride in some gorse plants that Lord Beale of County Cork, homesick for them, had shipped to himself in far Port Dido around the turn of the century, after he founded the town. The witch, napping amid the thorny prickles through the months of the sea journey to the Pacific Northwest, had lost track of her name when the vessel finally docked and she woke. Something to do with battles? Graculus or suchlike? Something about ravens? Never mind, it wouldn’t be the first name she had mislaid. Leaving the gorse, she caught sight of letters on the door sign of a small, sturdy building overlooking the dock. Harbormaster, they said. Port Dido.

Dido, she thought. That might do.

A cormorant nesting in a tree greeted her with a gentle, woeful croak. She grunted back at it, then climbed gratefully into the heart of its nesting tree, a sturdy spruce, and, still feeling the slightest bit seasick, she went back to sleep for a time.

When she finally emerged, the birds had gone, the tree had died of their guano, and there was considerably more of Port Dido than there had been before.

She half-saw, half-sensed that. She could see in the dark; she could understand the gist of the language of leaves. She could hear laughter within the tavern on an island up the estuary a mile away, and she understood the gist of that as well. Most around her were asleep, lulled by the distant roar of tide at the mouth of the bay. But not everyone.

Spring, she thought, smelling it. And then she saw the face of the moon.

It was full and luminous, a great wide eye above the high forests and the silent waters of the estuary. It was staring straight at her. So, she realized suddenly, was someone—something?—else.

A goddess, she thought, startled, and she heard herself bleat like one of the dark, snake-necked birds she had last spoken to. She was still invisible to humans, but beyond that boundaries got nebulous. This goddess she recognized as one that took her power from the moon, but she had no idea what name that power claimed in this ancient place.

Nor, she remembered, did she know her own.

“I need a body,” the goddess said inside the witch’s head. “It’s that time of the century. The one I have now is tired and needs a break.” Her sacred voice sounded taut, restless, barely constrained; the witch felt her own bones smolder and shine, becoming illuminated with the intense, radiant scrutiny. “You recognized me. You know me—”

“I did once,” the witch agreed, “but in a place very far away, and by a different name. Which,” she sighed, “I have completely forgotten, along with my own.”

“Perfect,” the goddess said briskly. “Listen. Do you hear me?”

The witch did indeed: the roaring, growling turmoil along the edges of the earth, the rear and smack, the long, long roll, the break and thunder, the slow hiss, the whisper and pop of clams dancing in the tidal foam.

“Yes, Mistress,” she said. She was fearless, adventurous—why else was she there?—and she had, as yet, no other place in the vast new world. Why not this?

“It’s only for a hundred years,” the goddess assured her. “And then you’ll find someone to take your place. You will be feared, loved, cursed, praised, studied; you will be the flow of life; you will be bitter death; you will serve the moon, the sea, and all those your foamy fingertips can reach. Oh, and you will be worshipped. They’re an odd lot, the worshippers, but very dedicated. You will be visible to them only once, near morning: the new face of my power.” The goddess’s voice was getting fainter, or the tide was getting louder, roiling into the witch’s heart, into her blood. Her foamy fingers seemed everywhere, all around and very far away, following the path of the moonlight down the long pull of water. “Look this borrowed body up,” she heard, “when you’re yourself again. It’ll be around.”

She had no time to answer, learning names, shapes for everything she touched: every scale, worm, new thin shell, tiny unblinking eye, every floating strand of grass, transparent thread of jelly, everything new, just being born, all at once it seemed and already as moonstruck as she.

In the darkest hours she had reached the far edges of her realm, exploring every winding channel, every narrowing stream, every churning edge where the tide sculpted the world to its shape.

That’s when she saw their fires and heard her name.

She appeared to them in the goddess’s shape: a being made of spindrift, eyes of iridescent purple-black nacre, hair white and wild as spume, a voice like the most tender lilt and break of foam. She greeted them. The figures around the fires, all human, all women, all went as still as the great trees above them, boughs lifted as though to receive the descending moon.

Then they leaped to their bare feet, laughing, clapping, calling to the goddess, the same word again and again, which, the witch/goddess realized sometime later, as she busily withdrew herself across the mudflats and back into the sea, must have been her name. Her final coherent thought for a century was that, once again, she had forgotten it.

A hundred years later, give or take the time the moon took returning to the full, the witch, exhausted and desperate for a change of shape, poured all the powers of the tidal goddess into the first likely body that gave permission. The body, half-human and half-local spirits, seemed surprised at the forces, but on the whole quite curious, and responded with alacrity to her changed state.

The witch, herself again, crept with great relief into the heart of a wooden female shape nearby and went back to sleep.

* * *

Jake Harrow and Scott Cowell were trying to load the seven-foot wooden mermaid with her scallop-shell bra and her long blue tail with the cormorant perched in its curve off one end of the Port Dido bridge into the back of Markham Cowell’s pickup truck when all hell broke loose.

It was after midnight and the town was asleep. Then it was dawn, or some lurid, colorless version of light, by which the two young men could suddenly see one another’s pallid, surprised faces beneath the mermaid’s cheery red smile. In the same nanosecond the bell in the tower at Our Lady of the Cormorants pealed like someone had whacked it with a tire iron, and a cannon blew off next to them. They leaped. The mermaid slid out of their hands and toppled toward the back of the pickup, which is what they had wanted her to do in the first place. But the pickup was no longer there, Markham having stomped the accelerator at the sound of the blast, sending the truck careening halfway across the bridge.

The mermaid fell on her back and slid down the embankment into the bay.

For one stark moment, by the light of the streetlamp in the middle of the bridge, they saw her smile under the shallow wash of the tide. Then she sank a little deeper into darker water. Markham and Jake stared at where she had been, and then at each other. Lights were flicking on all around them in houses on the cliffs and along the water, in the Marine Institute’s dorms, in the harbor where those who lived on their boats were scrambling onto the docks. There was a squeal of tires, a rattle of muffler as Markham backed wildly; Jake and Scott leaped to meet the truck, flung themselves inside.

“What the hell—” Markham breathed, shifting gears.

“Go,” Jake said tersely.

“Where’s the mer—”

“Go!”

They ventured back near dawn, on the off chance that the mermaid herself hadn’t gone anywhere, and they might winch her out of the water before anyone else noticed her. But the slowly awakening sky revealed nothing, except that, where mermaid had been, there was now none. Most, Jake guessed, were so used to seeing her they didn’t much notice her anyway, there or not. They would notice, maybe even remember, the three standing where she usually stood, looking down the bank for something in the water.

“Must have sunk like a stone,” Markham murmured bemusedly.

“Most logs don’t,” Scott argued. “They float.”

“Then she floated away.”

“Let’s take a walk on the docks,” Jake suggested. “Look for her there. The bridge is going up, and people idling here are going to notice our faces instead of hers.”

Fishing boats on the landward side of the harbor were heading out to sea. Two slabs of tarmac rose to sandwich air so they could get by, and traffic had begun to line up along the road. The three crossed between idling cars to where they had left the truck behind Sylvia’s Bait and Tackle. When the bridge folded itself down again, they drove across, and turned onto Port Dido’s single busiest street, where you could rent crab rings, buy groceries, find a beer and a barstool, or, at the far end of it, an education in marine biology. From there they took a side street, passed the fish-processing plant, several ancient restaurants, and the Landlubber, Port Dido’s only motel. The street ended in the parking lot beside the harbor.

The three walked down a ramp and separated on the docks to search between trawlers, sailboats, cruisers, motorboats, and scows for the mermaid that might have gotten washed between them and wedged there by the tide. Everyone Jake passed, crabbers with their rings in the water, boat people gathered for coffee on one another’s decks, talked about the same thing: the ferocious flash of light, the wild jangle of church bell like a call to judgment, the instantaneous detonation of thunder. Hell, he thought, even the harbor seals clustered on their favorite dock were probably barking it over.

Nobody mentioned the missing mermaid.

Yet.

She finally surfaced in the Foghorn Café where the three slid wearily into a booth for breakfast. The Foghorn cook, driving early to work, had marked the mermaid among the missing after that tumultuous night. Word spread quickly among the staff and passed to the diners along with every breakfast order. From what Jake could catch of the excited gabble, nobody was certain of anything, though nobody could get enough of it. The lightning, as sudden and vivid as a dead eye opening, the horrendous blast, the scarred, blackened bell tower, the vanished mermaid were puzzled over separately and together; nothing seemed to fit.

“That tall ship that comes to visit every year—the Lady Ysabelle—did she sail in last night? Maybe somebody shot off her cannon and hit the Cormorants’ bell? Maybe it took out the mermaid along the way?” Jake, who had his back to her, recognized the lilting ebb and wash of Carey O’Farrell, who owned Sea Treasures, in which tourists could buy wind chimes made of jingle shells, local art and jewelry, and Port Dido tea towels.

“The Lady Ysabelle’s not due until late summer,” Parker Yeong, one of the Institute’s professors, reminded her. “Besides, they only fire off gunpowder in their fake battles, not real cannonballs. I like your theory, though,” he added cheerfully. “It’s better than the single-bolt-of-lightning theory. That might explain the bell tower, but not the missing mermaid; she wouldn’t have been in its trajectory.”

“Yes, and what have those Cormorants been up to?” Emma Cadogan demanded darkly from the table on the other side of Carey. Her portentous, fluting voice caused Shirley Watson, of Watson Fishing and Whale Watching Excursions, to stiffen on her stool at the counter. “I always knew they are an evil bird. Blasphemous to think that the Mother of God would consort with cormorants.”

Shirley spun on the stool, her whacked-out, sideways grin flashing her gold eyetooth. “So the Lord flung a lightning bolt, missed the birds, but got the church tower instead?”

Markham loosed a snort of laughter over his coffee. Scott, red-eyed, rattled, punched his brother’s arm, but it was too late. Emma, loftily ignoring Shirley, trained her sights at the three young men in the booth. She was a massive, formidable woman who spent her hours at the Port Dido Visitors’ Center, telling tourists where to go and showing them the quickest way to get there.

“What do you boys know about all this?” she asked, riveting them in an instant, like that snake-haired Greek with the snarky eyes who lingered in Jake’s memory long after her name. “You must have been out late last night after graduation.”

Jake heard Markham’s breath again, freed from the stone he had almost become. “Graduated three years ago, ma’am,” he said with a genuine edge of indignation. “Last thing on my mind back then would have been a woman made of wood with a fish tail instead of legs.”

Emma’s eyes didn’t flicker, Jake saw; she might have pursued the matter for no other reason than to listen to her own voice. But Sally Goshen edged between table and booth wielding a tray full of breakfasts.

“Did you all hear what happened last night?” she asked them breathlessly. “I just heard—I started my shift late. I was home all the way over in Greengage when that bolt woke me and my son Jeremy and the dogs. Louise in the kitchen said her boyfriend was out with the Coast Guard late last night in a cutter, and they saw the entire bay bright as day when the lightning flashed. He knew it got the Cormorants because they’re the only church in the county with a real bell in the tower.”

Dr. Yeong swiveled from his breakfast burrito to look at her. “Did he know anything about the mermaid?”

“What? No.” She stared at him, giving Jake Markham’s mile-high stack with bacon and extra butter. “He didn’t say. Somebody found a mermaid?”

“No,” Carey explained. “The mermaid on the bridge? She went missing last night.”

“You’re kidding!”

“Vanished,” Markham said, gazing raptly at Sally’s face, with its skin like a ripe, golden, finely freckled apricot. Scott joggled his elbow; he looked vaguely around, then focused on his plate. “Heck’s this?”

“My Greek omelet,” Jake said. “Spinach and feta and capers.”

“Capers.” Markham speared one on a fork prong. “Looks like bait to me.”

“Oop—sorry,” Sally said, putting Scott’s salmon scramble in front of Markham instead. “Oh, yeah, that mermaid. Well? What happened to her?”

Jake shook his head, drawing in a deep breath of syrup and melting butter as he passed the pancakes to Markham, who handed his brother the scramble. “We have absolutely no idea.”

They parted company after breakfast, Markham to work catching and baiting fish with huge hooks to catch the cormorants who swallowed the fish, Scott to the community college over in Myrtlewood to study Spanish and welding, and Jake to the South Coast Culinary Institute to learn the difference between hollandaise, béarnaise, and mayonnaise, and which belonged on what.

* * *

The witch opened her eyes and found herself floating on her back with a cormorant sitting on her front holding its wings out to dry.

Her whole being, whatever it was at the moment, protested the wakening. It was far too soon after a hundred restless years; she needed most of a year to sleep, not half a night—and why was she back in the tide?

The bird opened its long beak soundlessly, seeming to sense the witch’s ire at the world through its great, flat feet. Then it levitated with a powerful, graceful thrust of its wings. The witch caught its eyes, its vision; for a dizzying moment, she looked down at herself, the wooden mermaid in the water, with her scallop shells and her bright yellow hair curved along her cheek and one side of her smile, her long tail curved upward, fin spread like a fan, the arc broad enough to hold something, the cormorant maybe, that might have perched there.

Oh, why not, the witch thought with exasperation. At least human, I could have a bed.

She guided the wood figure carefully away from fishing boats in the bay, from boat ramps and docks crowded with crabbers. Passing gulls took note of the mermaid’s glowering eyes and changed their minds about landing there. After a century, the witch knew the waters—estuary, harbor and bay, every stone, barnacle, and bit of wrack—like she knew her own mind. She brought the stiff, heavy statue easily and unobtrusively to the sandy shore inside a half-hidden cove. There she let her powers flow everywhere into the wood, just as she had for the last century. Eyes blinked, hair shifted in the wash of water, the tree heart thumped, sap moved along its secret ways. The witch swallowed, spoke, making a hollow blat at first. When she tried to stand, she remembered what she had forgotten. Fin morphed into feet bigger than any she had ever had. She stumbled over them at first, and nearly bumped her head on the rocky ceiling. She touched her hair, examined her toenails, gazed with bemusement at the two scallop shells on her chest, no longer wood but real, and at the short, wetly gleaming, scale-patterned blue skirt that barely reached halfway down her thighs. She possessed nothing else: no shoes, no money, not even, she realized irritably, a name.

“Maybe,” she said aloud, then, remembering, and her smile appeared, a living thing as responsive to her thoughts as language. “Maybe in this body I’m Dido.”

She vanished for a while to climb up the cliff above the cave, a simple matter for her great, splayed feet and her long, hard arms; then she walked a back road down into Port Dido.

She let her oddly tall, ungainly but comely shape appear gradually on the sidewalks: a barefoot, very tired, very hungry young woman wearing only seashells and fish scales. People had changed, she noted with interest, during the hundred years she’d been in the water. Like the mermaid, they exposed anything at all of themselves, and much of what they exposed had colorful artwork on it, as though they kept their histories in living canvases on their skin. They let their hair do whatever it wanted; they put extraordinary things on their feet. Even so, some still gave her startled glances. Others grinned at her, or extended a thumb, which meant something, she guessed: maybe it warded away witches.

She was dawdling outside a cluster of shop windows in a little square, intrigued equally by the clothes in one, the bottles of wine in another, the little tarts and buns in a third. Her mouth watered; her chilly fingers and feet tried to warm each other. Money, she remembered distantly, was the difference between having nothing and having something. At least it was for mortals, but not necessarily for witches inhabiting the shape of a wooden mermaid turned temporarily human. She was debating in the mermaid’s head the merits of pickpocketing, begging, scaring the change out of the next passerby, or enchanting a few dried leaves into coins, when a shop door flew open.

“There you are! I’ve been keeping an eye out.” The witch, surprised by the young, brown, dark-browed face peering out, recognized under the thick curly hair and the flawless skin of someone not long in the world the force that had been the tidal goddess’s previous body. She was part cormorant, the witch sensed, and part human, with some very old regional powers tossed into the mix. Like the witch herself, she’d been around a long time, and had many connections, not all of them innocent or unambiguous. “Come out of the cold. Port Dido blows in a fog bank every afternoon and calls it spring. I’m Portia. Did you remember your name?”

“Not yet,” the witch answered, crossing the threshold. “But I’ve decided the mermaid is Dido. It’s easy to remember.” She smelled all good things then: meat, fruit, chocolate, fungi, grains, spices, and her knees shook. She sat suddenly; a chair caught her midway down.

“You poor thing.”

“Something woke me before I had even begun to dream. I’m not sure what it was, but I found myself in this—this—”

“Yes.” A dimple deepened in one firm cheek; in her smile a bit of ancient mischief sparked. “You did. I can give you a place to sleep for a hundred nights. Or I can give you dinner, a bed for the night, and a job in the morning. Not too early,” she added quickly. “Pub hours. Your choice. Here. Eat this.”

The witch, biting into strawberries, thick, heavy cream, dark chocolate, and golden pastry that crumbled and floated in air, decided in that moment, that mouthful, to stay awake and human for a while. There were benefits.

“But what do you get out of it?” she wondered. Even the most noble of witches had her own best interests at heart.

Portia dropped the lid over an eye dark as the backside of the moon.

“You’ll see.”

* * *

By the week’s end, opinion seemed pretty evenly divided between blaming the mermaid’s disappearance on the congregation of Our Lady of the Cormorants, whose passion for the demonic bird must have led them into unimaginable wickedness, or the Port Dido High School’s graduating class, which was known for its pranks, or any of the rich tourists who might have driven off with the mermaid as a souvenir of the quaint little town where they had hired a boat for a day to haul salmon and tuna out of the sea. A reward donated by the Chamber of Commerce was posted for information leading to her whereabouts. Merchants set out donation jars to add to the reward. The local paper published a photo of the missing mermaid, the history of her life on the bridge welcoming visitors, and a plea from the chainsaw artist who had created her to return his master work, no questions asked.

Jake’s girlfriend, Blaine, pretty much said the same thing, wailing into his cellphone as he sat with Markham and Scott in a shadowy corner of the Trickle Down Brewery and Pub, “Jake, how could you lose a seven-foot mermaid? You have to find her. I promised Haley! I promised her! That’s the focal point of the whole color scheme of her wedding. My best friend is getting married and I want her day to be perfect. I don’t care where she went, you have to get her back by Saturday.”

“I know, baby,” Jake said softly. “I will. Ah—where are you?”

“Here at Haley’s with the girls, making the wedding favors. Oh, don’t worry, nobody’s here who doesn’t know you’re involved. Everything—the favors, the cake, our heels and dresses, the bouquets, the corsages and decorations—they’re all her colors! Red and that dark, gleaming blue with yellow trim for her hair. Nothing will make any sense without her. You were just supposed to borrow her for a few days then put her back, not drop her into the bay.”

“It just happened,” he answered helplessly.

“I know, I know: the lightning whacking the church bell, the thunderclap—I understand that. But why did it have to happen to Haley?”

“We still have until Saturday. We’ll find her.”

“What can I get you guys?” the waitress asked.

Blaine’s voice grew small and far away as Jake stared. She wasn’t covered in blue scales; she had two legs under a short black skirt and black tights. But that red mouth, that generous smile, the curve of golden hair along one side of the smile, all that and the fact that she was taller than anyone in the room made his thoughts tangle to an abrupt halt, like an engine seizing up. He ended the call absently, forgetting Blaine. Beside him, Markham and Scott were absolutely still.

“Guys?” She twiddled the pencil between her fingers against the order pad. “Drinks?”

“You—” Jake breathed. “You.”

“Oh, for—” She gazed at them with pity, one hand on her hip, and shook her head. “No. I am not the Port Dido mermaid come to life. What is it with everyone? I was the chainsaw sculptor’s model. That’s all.”

“Lived here all my life,” Markham managed. “Never saw you before.”

“I’ve never lived here before.” She raised the pencil. “Let’s try again. What can I get you?”

She took their orders. They watched her return to the bar; then their heads swiveled slowly; their eyes met.

“No,” Jake said flatly, to his own and everyone else’s unspoken suggestions.

“But the timing—it’s got to be more than coincidence,” Markham said weakly.

“So? What?” Scott demanded. “So she really was a wooden mermaid a couple of days ago and the fall into the water turned her human?” He batted the back of his brother’s head lightly. “Get real.”

They were silent, watching her again. Markham mused, “She could come to the wedding anyway. Couldn’t she? Don’t suppose Haley would—”

“No. I don’t suppose Haley would accept a human substitute dressed up as the Port Dido mermaid. Especially not one who looks like that.” Jake drew a sudden breath. “Did I really hang up on Blaine? I’d better call her back.”

The mermaid returned with their drinks. Their expressions transformed her enchanting smile into a broad grin. “Don’t worry,” she said briskly. “You’ll get used to me.”

* * *

On Sunday, the witch went to church.

Our Lady of the Cormorants was a modest chapel framed by a stand of old fir trees, its altar windows overlooking the blue-green estuary. Though its bell tower, tall and rounded like a tree trunk, had been scorched by the lightning, the bell still called the congregation to gather with a sweet, mellow toll. The congregation, the witch who called herself Dido noted, seemed to be all women. In fact, they were all witches with some level of power, though not all of them knew it. They simply felt comfortable, the witch guessed, among the eccentrically skewed worshippers dedicated to the smiling statue generically clothed in a long white robe and a blue mantle, her open hands outstretched over the dark pair of wiry-necked, long-billed, waddle-footed birds gazing up at her.

Seated on a pew smelling of cedar and candlewax, the witch napped through most of the service, waking only when the pastor, Reverend Becky, unsheathed an edge in her gentle, soothing voice.

“It’s that time again, Ladies. Those of you with cormorant heritage will need to find and waken those powers to protect the nestlings from predators. Especially from Niall Parker at Davy Jones’ Liquor Locker, who harpoons nests at night when he’s drunk, and Markham Cowell, who gets paid to stuff freshly dead fish with hooks and run them fast underwater to attract the parent birds. Those who can will circle the nestling trees and grounds with your darkest powers so that humans can’t pass among them. Those with other powers: get creative. Invent noises to scare the predators, swamp their boats if you catch them shooting the birds from the water, put whatever charms and distractions you dream up in places where they’ll do the most good. Keep eyes and ears open for trouble, and stop it if you can before it starts. We are the faithful of our Lady of the Cormorants. It is our belief that we are all—even idiots like Niall and Markham—part of Holy Mother Nature, that we all belong to this earth, that cormorants are of an ancient and wild power that should be protected, and that the sea will provide for us all, human and bird, if we take care of one another and the sea. Amen, Ladies.”

“Amen.”

“Please stand for the closing hymn.”

The witch yawned a great yawn, sent her body sprawling along the suddenly empty pew and went back to sleep.

She woke up in a tree.

It was night. She was surrounded by dreams of a fishy, feathery, egg-nesty kind, fraught with swift flights over water, sudden, deep dives, the struggles to stretch and shape a long throat and neck around the body struggling equally to wriggle out of them. She had to shield her human nose from the acrid smell of guano on the tree limbs, which seemed to cover them like perpetual moonlight. Parents, half-waking in their twiggy nests, made little blats and moans around her, disturbed without knowing why. The witch woke up a bit more, spread her rangy self more comfortably along the boughs, and got around finally to wondering why she was up a tree.

She heard voices.

The patch of forest, between the shops at one end of the street and the Institute at the other, overlooked the bay and a small beach over which the low tide gently sighed and slid, sounding like a contented dreamer. The only lights were distant: from the dorms, from vessels in the marina, from the occasional streetlamp. The half-dozen men gathering under the nesting tree had no reason to be quiet; the wakening parents above, some nervously croaking, weren’t going anywhere. The men, the witch observed dourly, weren’t much more articulate.

“Whaugh, this place stinks. Who’s got the bottle?”

“Here.”

“That one there, Niall. That big nest, higher up. Harpoon that one and it’ll pull the others down along the way.”

The witch heard a gulp, a spit, a sudden, sharp laugh. “Last time you’ll snarf our fish, you up there. Look at them. All they do is eat and breed, make more mouths to take the fish out of ours. Do it, Niall.”

A light went on; it searched the tree, falling short of where the witch sat. She could see a reddened, raspy face or two, the hands of the harpooner adjusting his line, raising the long weapon with its sharp, glinting dart, taking aim.

Get out, Portia’s voice in the witch’s brain said very clearly. Fast. Now.

There was a grunt, a whip of line, and a strangely solid thud. The witch, balanced precariously on the very tip of the tree, once again invisible, heard branches cracking, something heavy careening through them, men shouting in warning, the bottle breaking.

The thing finished its fall with a massive thud in the middle of the road.

There was utter silence. The witch, all her senses galvanized, powers she had forgotten she possessed, crouched, alert, waiting to attack, finally heard a dry swallow below.

“Damn, Niall. You harpooned the Port Dido mermaid.”

Selection from “Mer” excerpted from Dreams of Distant Shores © Patricia McKillip, 2016