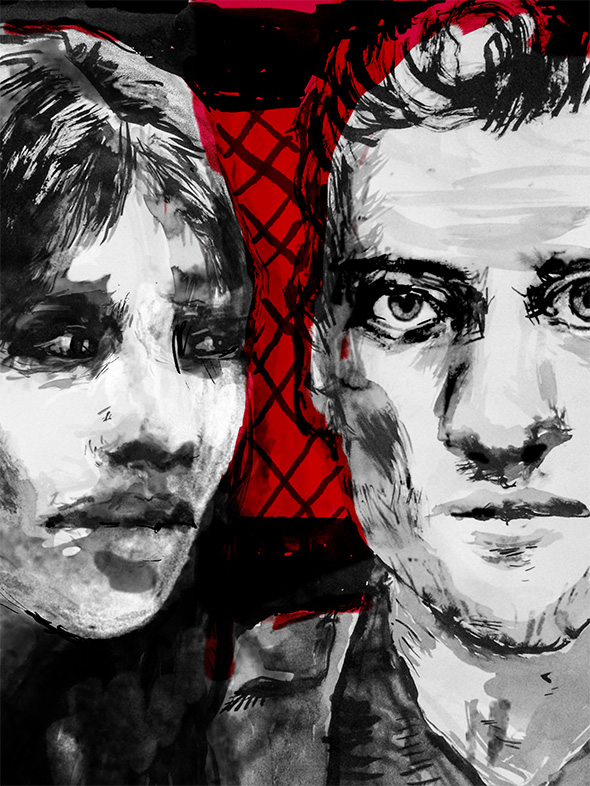

It sounds like a joke: An SFF/speculative fiction author and a robotics law expert come together to talk about a killer sex robot. But it’s actually part of Future Tense, a partnership of Slate, New America, and Arizona State University to explore how emerging technologies are changing our lives. While past Future Tense installments have included screenings of The Terminator with robotic experts and panels on genetic engineering or nuclear energy and environmentalism, this week takes a different approach: The Water Knife author Paolo Bacigalupi has written “Mika Model,” a short story about a sex robot who murders her owner (or does she?); and Ryan Calo, a law professor with a specialization in robotics, has penned a response.

In this noir-y tale set on a drizzly Bay Area night, Detective Rivera finds himself faced with a conundrum: A Mika Model—the faux-innocent sexbot advertising her better-than-human services all over TV and his browser history—has showed up at the police station carrying a severed head and asking for a lawyer. But is her crime murder, or an unfortunate product liability? And even though she looks and sounds and feels human, does Mika even have the right to due process?

Bacigalupi’s exploration into this thorny intersection of hard law and software immediately brings to mind Alex Garland’s Ex Machina: Both center on a stunning woman who has crossed the Uncanny Valley with ease, who can not only ace a Turing test but charm the tester as well. If Ava’s and Mika’s creators can program them to act truly human, doesn’t part of that involve the capacity for manipulation? As Rivera uncomfortably reflects:

She stirred, seemed to gather herself. “Does that mean you won’t charge me with murder?”

Her demeanor had changed again. She was more solemn. And she seemed smarter, somehow. Instantly. Christ, I could almost feel the decision software in her brain adapting to my responses. It was trying another tactic to forge a connection with me. And it was working. Now that she wasn’t giggly and playing the tease, I felt more comfortable. I liked her better, despite myself.

“That’s not up to me,” I said.

“I killed him, though,” she said, softly. “I did murder him.”

Calo picks up this dilemma in his response, examining the mens rea, or intent to kill, that accompanies a murder charge. If Mika is capable of experiencing pleasure, pain, and a whole litany of emotions, does that create enough of a case for intent? Further, she possesses social valence, i.e., a pull that causes humans to anthropomorphize her; it seems almost inevitable that she would be treated like a human. But where does her manufacturer, Executive Pleasures, come into this? Is there a clause in their terms of service that extends to deaths caused by a Mika Model?

Most interesting, however, was Calo’s explanation of not just the rights of people involved in crimes, but the responsibilities:

Fueling this intuition was not merely that Mika imitated life but that she claimed responsibility. Rights entail obligations. If I have a right, then someone else has a responsibility to respect that right. I in turn have a responsibility to respect the rights of others. Responsibility in this sense is a very human notion. We wouldn’t say of a driverless car that it possesses a responsibility to keep its passengers safe, only that it is designed to do so. But somehow, we feel comfortable saying that a driverless car is responsible for an accident.

To talk of a machine as truly responsible for wrongdoing, however, instead of merely the cause of the harm, is to already side with Mika. For if a machine is a candidate for responsibility in this thick way, then it is also a candidate for the reciprocal responsibility that underpins a right. The question of whether Mika intends to kill her owner and the question of whether she isentitled to a lawyer is, in many ways, indistinguishable. I see that now; I had not before.

You should read both “Mika Model” and its accompanying response, and check out more of the thought-provoking conversations Future Tense.

Natalie Zutter is fascinated by whether (sex) robots have rights or not. Chat with her about it on Twitter!