If publishing a book takes one year, then why do George R. R. Martin’s publishers only need three months? Learn how blockbuster novels can change the book production process.

Update: In early 2017, Martin said that he thinks that The Winds of Winter “will be out this year.”

George R. R. Martin’s New Year’s update on the progress of The Winds of Winter, while noting that the novel currently has no projected completion date, contained an interesting detail regarding production of the book:

[My publishers] already had contingencies in place. They had made plans to speed up production. If I could deliver WINDS OF WINTER by the end of the year, they told me, they could still get it out before the end of March.

Book production, from the delivery of the manuscript to the book arriving on shelves, typically takes nine months to one year, so how is it that Bantam and Martin’s non-U.S. publishers could turn around an undoubtedly massive work like The Winds of Winter in less than three months? Learn about the typical book production process below, along with how unique marquee titles like The Winds of Winter can circumvent, compress, and alter that process.

Book production processes differ depending on the type of content featured in a book. Full-color art, for example, adds time to a book’s production process by requiring additional outlay for printing, extra time to clear the usage of images, and/or extra time to prepare and create additional images. An image-heavy non-fiction book can add even more time to a production process by requiring rigorous fact-checking in addition to content editing. In comparison, the production process for a text-only fiction title like The Winds of Winter is straightforward.

Market forces also affect the production process of a title. While a novel begins as a work of personal expression by its author, it will eventually be seen by a bookseller as primarily a product. The task of a publisher is to balance the artistic expression of the author with the demands of the marketplace on the product. For a debut author, the publisher and bookseller must work together to generate initial demand for that author and their story. In George R. R. Martin’s case, booksellers want the product as quickly as possible, so a publisher’s task becomes maintaining the integrity of the writing while satisfying the intense demand for the product.

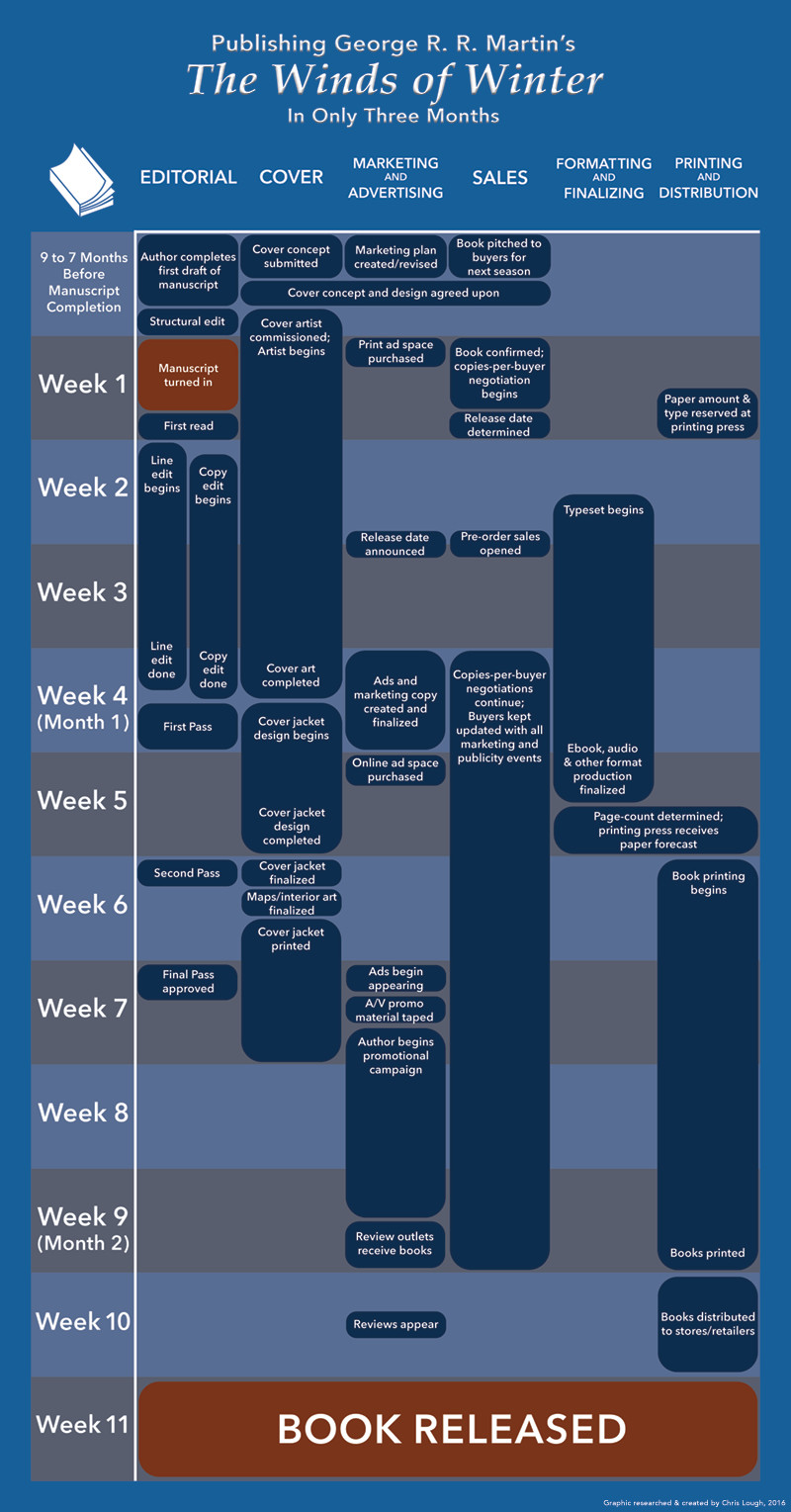

The production process is broken into six steps below, with an overall explanation of how the process typically works, coupled with speculation on how that process could be condensed into a span of three months. It should be noted that some of the terminology used may be publisher-specific, even though the terminology describes a universal process within the industry.

Skip to:

- Editing

- Cover Art

- Marketing and Advertising

- Sales

- Formatting and Finalizing

- Printing and Distribution

- How Much Time Could The Winds of Winter Take? (infographic)

- Why Isn’t Every Book Published This Quickly?

Book Production, Step One: Editing

The production process for a novel like The Winds of Winter officially begins in earnest once the author turns in their completed manuscript, and editing occurs throughout and even before this process. When a fantasy series is initially sold to a publisher, this often includes a rough outline for the entire series, book by book, so that the publisher has some idea of the investment it is making. This outline will change, sometimes drastically. Martin’s original plan for A Song of Ice and Fire was only three books long, and was markedly different than the books readers actually received. Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time famously grew from a trilogy into fourteen books.

Editors are aware of the changes that occur organically to these outlines over the course of a series’ publication, and periodically conference with authors in regards to future plans for the plot structure and length of a series. Martin is again notable in this regard, having famously split A Dance With Dragons into two books after consulting with his editor Anne Groell at his publisher Bantam in 2005. A complex series like A Song of Ice and Fire is always undergoing a big-picture, structural editing process, and The Winds of Winter is no different. In fact, structural editing on The Winds of Winter stretches all the way back to the final edits on A Dance With Dragons, where it was decided to push certain completed chapters and events to the forthcoming sixth volume of A Song of Ice and Fire.

For many book series, editing begins before the manuscript is completed, and this is often necessary for fantasy series in particular. “Editing a series with continuing characters or an ongoing narrative is so much more complicated than editing a standalone,” notes Marco Palmieri, an editor at Tor Books who oversees Brian Staveley’s Chronicles of the Unhewn Throne fantasy series, as well as Max Gladstone’s fantasy/urban hybrid Craft Sequence series. “In part this is because of the importance of maintaining continuity across books. The details of events, characters, places, etc. need to track from one novel to the next, or you risk pulling the reader out of the story with a contradiction.”

Once a completed manuscript is turned in, the detailed editing process begins. An editor gives the manuscript a “first read,” often making notes along the way. The length of time taken up by the first read is subject to the editor’s work and life schedule. Are edits on their other books more pressing? Is this being read during conference season, when the editor is often traveling a lot? Is there a major life event, good or bad, that the editor is dealing with? Are there substantial administrative tasks that the editor must clear off their schedule first? Administrative work actually takes up a substantial amount of an editor’s office hours, often shifting a first read into what would be known as personal hours in a 9-to-5 industry. Since a first read needs to be focused, an editor usually must schedule out several continuous, uninterrupted hours to accomplish it. This can be a marathon reading over the course of two days, or it can be split into portions of time throughout a two to three week span.

Once a first read has been completed, the editor then sends the author their notes on “structural” edits. Structural edits are BIG requested changes to a manuscript: Combine these two characters, change the setting of that second act so that it doesn’t take place entirely on a boat, don’t kill Arthur Weasley, and so on. Palmieri elaborates on one of the unique editing challenges for fantasy series: “There’s also the risk that a later book in a series will rely too heavily on the reader’s knowledge of the previous books. Ideally each novel should be able to work as a standalone while avoiding the trap of info-dumping—which is to say, including awkward chunks of exposition—to remind the reader about what has gone before. Those books need to somehow strike a balance between serving the larger metastory they’re part of and working independently of that metastory—without compromising the pacing and flow of either the novel or the series.”

An author needs time to make these large-scale changes, as they often involve writing entirely new chapters or passages for the book, so an editor usually sets a deadline for the structural edits at one to three months after the edits are requested. (When an author states on social media that they’re going radio silent because they need to work on edits, this is sometimes what they’re referring to.) The time taken up by a first read and structural edits varies significantly, and can stretch from a rapid three weeks to a “languid” four months. Two to three months is usually the norm for this process.

Once the structural edits are approved by the editor, the manuscript is “accepted” by the publisher and a laser-focused line edit process begins. Line edits are just what they sound like, a line by line editing of an entire manuscript. The editor typically champions this task, keeping the author in the loop in regards to questions or significant changes that the editor wants to make to a line. This can be something as simple as correcting a homophone or deleting a repeated reference (such as Davos clutching his finger bones). Or the edit can be something significant, like changing the tone of dialogue to make a chapter read differently in comparison to the chapters before and after. Sometimes the simple and complex line edits are the same thing, like when a singular word choice abruptly reveals the answer to a series-long mystery. Line edits take a variable amount of time depending on the size and complexity of the manuscript and the series it takes place within, but they typically do not stretch beyond two months.

After line edits, the manuscript is sent out for copy edits. These can be handled by the author’s editor or by a separate editor specifically tasked with copy edits for multiple titles. Copy edits correct lingering grammar and spelling errors, and are focused on technical corrections and continuity rather than content and tone corrections. This process usually does not take more than a month, but is subject to the length of the manuscript and the availability of the copy editor. (Many authors, especially in the fantasy genre, work with a preferred copy editor who is familiar with the world’s terminology and the author’s voice, rather than a copy editor who must learn these from scratch. Having a consistent copy editor for a series also makes continuity errors easier to catch.)

Once these edits are completed, the publisher and author now have a working draft of the manuscript that is very close to its final form. (For our purposes we’ll call it the First Pass, but the terminology differs from publisher to publisher.) This pass is close enough to the final version of the book that Advanced Reading Copies (ARCs) can be made from it to be sent to reviewers and booksellers.

Taken altogether, the editing process from first read to First Pass usually takes six months.

How the editing process could be shortened for The Winds of Winter:

George R. R. Martin is an editor himself, and has stated multiple times on his Not A Blog online journal that he incorporates and executes both structural and line edits while writing the initial draft of any given A Song of Ice and Fire manuscript. From his Winds of Winter update:

Chapters still to write, of course… but also rewriting. I always do a lot of rewriting, sometimes just polishing, sometimes pretty major restructures. […] I worked on the book a couple of days ago, revising a Theon chapter and adding some new material, and I will be writing on it again tomorrow.

For A Song of Ice and Fire book, the first read and structural edits are already completed by the time the manuscript is turned in. This compression of the structural editing process is generally not ideal for crafting a story, as it eliminates months that are necessary for feedback from sources outside of the author, and makes large structural changes gathered from that feedback nearly impossible to implement. Books always benefit from a six-month window of editorial feedback, whether they are fiction or non-fiction, but A Song of Ice and Fire presents a unique situation in that its author has editorial skills he can bring to bear during writing.

Martin’s perspective on editors is complex, but a speech he gave at Coastcon II in 1979 offers some insight as to how he prefers the relationship between editor and author. Although the text vacillates between serious criticism and tongue-in-cheek frivolity, the following passage seems relevant to Martin’s current work:

What is a good editor like? A good editor offers you decent advances, and goes to bat with his publisher to make sure your book gets promoted, and returns your phone calls, and answers your letters. A good editor does work with his writers on their books. But only if the books need work. A good editor tries to figure out what the writer was trying to do, and helps him or her do it better, rather than trying to change the book into something else entirely. A good editor doesn’t insist, or make changes without permission. Ultimately a writer lives or dies by his words, and he must always have the last word if his work is to retain its integrity.

This statement gives some insight into the structural editing that Martin undertakes while writing A Song of Ice and Fire book, explaining why that lengthy step can be skipped when considering the production process for The Winds of Winter. Adam Whitehead goes into further detail here in regards to how structural edits are incorporated into the writing of A Song of Ice and Fire. Martin’s work process is quite fascinating.

The subsequent line editing and copy editing processes can not be skipped in the same manner. However, for a title as hotly anticipated as The Winds of Winter, external market forces, a publisher’s annual profit quota*, and the intensity of consumer demand for the book would ensure that once a manuscript was completed, George R. R. Martin and his editors would be working on nothing but that book, hour by hour, day by day. So while the intensity of demand wouldn’t necessarily shorten the editing process, it would guarantee an immediate and uninterrupted editing process.

*Note: While not the sole driver of a book’s publication, a publisher’s profit for the year is an oft-overlooked motivator for the quick publication of an anticipated bestselling book. Publishers are businesses, and must generate profit. No business would ever delay releasing its highest-selling product unless that product—in this case a book—was not completed.

Time can be saved on line and copy edits by staggering both editing processes in relation to each other, so that line edits and copy edits can take place at nearly the same time. For example, if a single chapter is line edited in one day, it can then be sent for copy editing the next day. That chapter then gets copy edited while the ensuing chapter is line edited, ensuring that the completed copy edit is only one day behind the completed line edit. This is a common staggering for many highly-anticipated bestselling books to undergo, so while it is a lot of focused and intense work, it isn’t entirely unexpected by the editors involved.

Pre-editing a book structurally and staggering line and copy edits can shorten the time between first read and First Pass from six or more months to around one to two months, with the bulk of that taken up by the line and copy edits. The most recent Song of Ice and Fire books, A Dance With Dragons, underwent this very process, going from manuscript to completion in only two and a half months.

Book Production, Step Two: The Cover

Calling the cover “step two” is a bit misleading, as a book’s cover is usually commissioned before a manuscript is turned in.

For most books in the science fiction and fantasy genre, the cover is often the first aspect of a book to be finished, as covers can take just as much time as a manuscript to finalize, but need to be done well before the manuscript in order to be used for marketing and sales purposes. (More on this in steps three and four.)

In order to begin work on a book’s cover before the story itself is finished, the author and editor put together a cover concept that can be given to their publisher’s art director or otherwise used to commission a cover directly from an artist. Sometimes this can be scene that, while still in rough form, both the editor and author know will remain central to the book. (For A Memory of Light, the final Wheel of Time volume, artist Michael Whelan was shown the rough draft of a short passage from what would eventually become the end of Chapter 23, “At the Edge of Time.”) For many books, the artist has a complete manuscript to work from, so they’re able to include contextual imagery. (For Brandon Sanderson’s The Way of Kings, Whelan had access to the entire manuscript, which resulted in a cover that captured various visual elements drawn from the book.) For more icon-centric covers, sometimes all an author needs to provide is an idea for an icon or color that evokes the book’s overall theme.

With the cover idea firmly in hand, the editor or art director confers with the marketing, advertising, and sales departments in order to get a sense of what kind of audience the author and publisher want the cover to appeal to. Once a clear direction is determined, artists are contacted whose style matches that visual direction.

Artists work with a variety of different methods. They sculpt, paint by hand, photograph, manipulate, illustrate through Adobe or Maya, and much, much more. Regardless of the artist’s chosen method of creation, it is best to commission a cover from an artist two to three months before the point where it is needed for the book’s overall production process. Irene Gallo, Art Director for Tor Books, explains, “Artists aren’t actively working on a cover that long, but the more well-known artists will be booked up months ahead of time. Typically it takes an artist about two weeks to create a cover once things get rolling, but they spend the time before that thinking the concept through, reading the manuscript, scheduling models, procuring props for photo shoots, and so on.”

Cover art goes back and forth between the artist, director, and editor for tweaks. While the art is being finalized, the design of the book’s cover begins. The design process is what takes all the disparate elements that will appear on a book cover—the cover art, the title, author name, publisher logo, additional text, etc—and brings them together into a complete book jacket that will call out to readers from bookstore shelves. For new books, almost all of these elements need to be designed from scratch, which involves type, color, and layout manipulation or creation. “Design takes another couple weeks,” Gallo adds. “It could be shorter but you need to factor in the designer working on many books at once and any extra time needed to work out more difficult designs.”

The cover creation process for most books typically takes between two to four months and is done parallel to the editing of the manuscript. Once a cover is completed, it is then shown to booksellers during the sales process. Large booksellers (like Target, Barnes & Noble, or Amazon) will ask for additional cover tweaks based on how they want to position the book in their stores. The art and sales departments will negotiate these tweaks and settle on a final cover.* This final cover will be included in marketing and advertising materials that the publisher uses in the lead up to the book’s actual release. This is also around the time that the cover is revealed to the reading public.

*In some extreme instances, booksellers will reject a cover entirely, necessitating the design of a new one. Knowing what a retailer will reject and accept beforehand is considered when the cover concept is initially created.

In total, the cover creation process can take about four months, and the approval process can take another three, depending on when in a bookseller’s purchasing season the cover is completed. This process can be even longer if a cover is rejected in the late stage.

How the cover creation process could be shortened for The Winds of Winter:

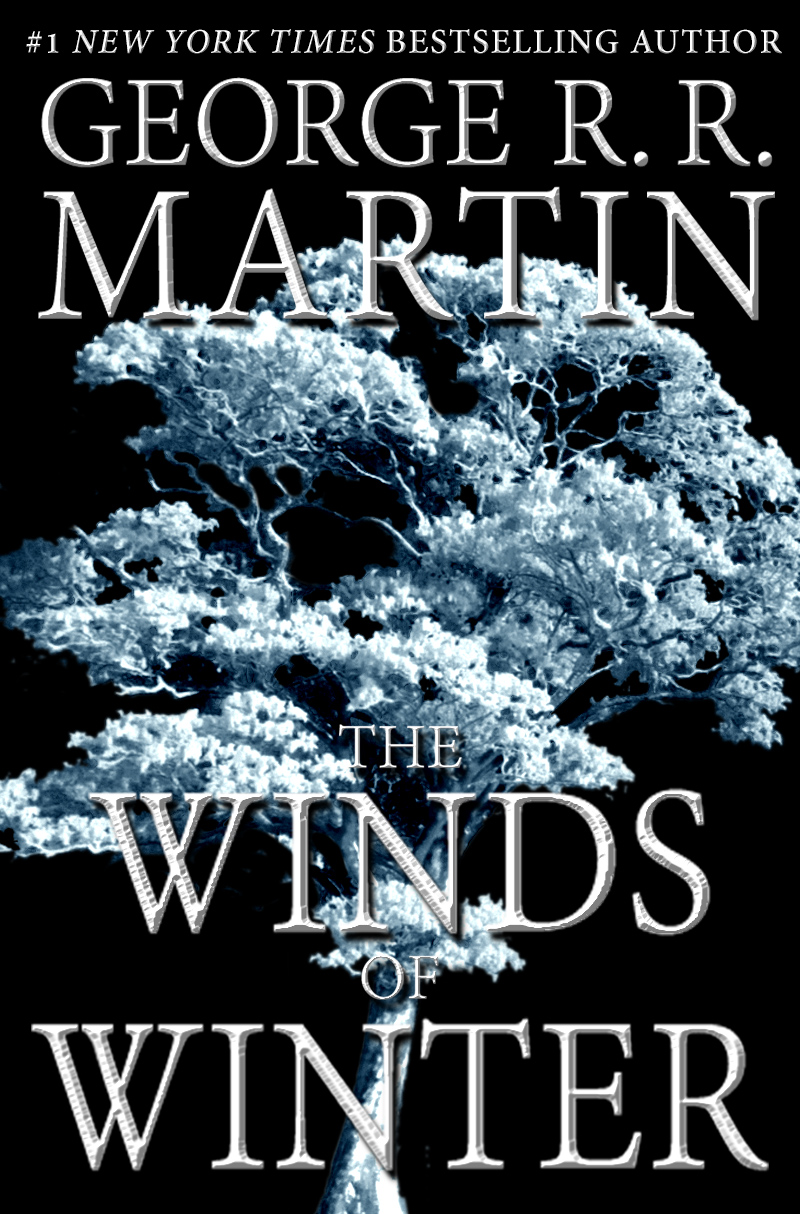

The Winds of Winter has a number of shortcuts available to its cover creation process. Upon the release of A Dance With Dragons, the covers for every book in the series were reconfigured into a unified series design, with each book now featuring the same type font, along with a particular color and series-evoking icon. A Game of Thrones is blue and features a sword; A Clash of Kings is gold and features a crown; A Storm of Swords is green and features a helmet, and so on. Although we don’t yet know what the final cover for The Winds of Winter will be, George R. R. Martin has confirmed in his January 2nd, 2016 update on the progress of the book that the mock-up cover pictured here is the current working cover. (Note: This article previously stated that the cover pictured here is a fan mock-up. The original paragraph can be found in Corrections at the end of the article.)

The Winds of Winter has a number of shortcuts available to its cover creation process. Upon the release of A Dance With Dragons, the covers for every book in the series were reconfigured into a unified series design, with each book now featuring the same type font, along with a particular color and series-evoking icon. A Game of Thrones is blue and features a sword; A Clash of Kings is gold and features a crown; A Storm of Swords is green and features a helmet, and so on. Although we don’t yet know what the final cover for The Winds of Winter will be, George R. R. Martin has confirmed in his January 2nd, 2016 update on the progress of the book that the mock-up cover pictured here is the current working cover. (Note: This article previously stated that the cover pictured here is a fan mock-up. The original paragraph can be found in Corrections at the end of the article.)

Since the Song of Ice and Fire books already have a bookseller-approved template, typeface, and design convention, all that Martin’s publisher really needs to do is commission a new cover from the series’ usual cover artist, Larry Rostant.

If you’ve gone anywhere near the science fiction, historical, romance, or fantasy novel sections of a bookstore in the past ten years, then you’ve seen Rostant’s work. The artist produces eye-catching, vibrantly-colored, sharply-lined covers that work for a variety of genres and as such, Rostant is usually in high demand as a cover artist.

Would Bantam have to wait two to three months for Rostant to produce a cover for The Winds of Winter? Not necessarily. Publishers can pay extra for a rush job, although that’s not an ideal situation for a book which will be iconic unto itself, and which the author and publishers know will be seen everywhere. Still, Rostant could most likely produce a finalized cover two to three weeks after The Winds of Winter manuscript comes in.

Considering the design template of the Song of Ice and Fire book covers, though, it’s quite possible that George R. R. Martin’s publisher has commissioned a cover months before the manuscript’s deadline, and that the book jacket is already designed and completed. To accomplish this, all Martin would have to do is tell his publisher that The Winds of Winter should feature a raven, a wolf, an icicle, etc. on the cover and the artist would be able to take it from there.

Additionally, a cover would not be necessary for the marketing, advertising, and sales efforts being undertaken for The Winds of Winter, due to the already-high demand for the book and the established brand recognition of the series’ name, the author’s name, and the book titles. Ads that utilized the series’ title in its established typeface could suffice as visual material.

The cover for The Winds of Winter presents very few barriers for quick publication of the book. As we can see, a draft version has already been created and only needs design finalization to be ready for publication.

Book Production, Step Three: Marketing and Advertising

Marketing is a vital step in the overall book production process, but since the work involved is so wide-ranged it can be difficult to realize its importance. To make the concept even hazier, marketing sometimes works best when you don’t even know it’s there!

In the very simplest of terms, marketing is the process of making audiences aware of a product, then successfully getting them to purchase that product. Book publishers often have internal marketing departments responsible for raising awareness of that publisher’s output, but there are also independent marketing and advertising firms that a publisher can contract this work out to for specific product campaigns. Authors usually work through the publisher’s marketing department (or marketing contractors) but are also free to contract marketing firms, and are especially encouraged by a publisher to undertake marketing work on their own.

Marketing work is comprised of numerous tasks, ranging from the broad to the granular in scope. One minute a marketer will be sending an ARC to a book blogger, the next minute they’ll be finalizing the art for a five-figure book advertisement in a nationwide outlet. Then the minute after that they’ll join forces with the Sales department to convince an unorthodox retail outlet (Victoria’s Secret) to package a specific book (A book I’m making up called “Epic Fantasy Lovemaking*,” let’s say.) that would pair well with that store’s product (lingerie) and appeal to a segment of that store’s captured audience (women buying products that are predominantly for male appeasement). Then the minute after that they’ll be conducting detailed market research for another potential audience outside of their usual readership. As you can see, the various tasks of book marketing can get complex, and the more complex those tasks are, the more fluid the deadlines for those tasks needs to be. Marketing is a surprisingly high-pressure job, and compressing this work into only three months can, understandably, increase that pressure.

*I would actually read this book. But I wouldn’t dare to Google it.

Marketers have established channels and audiences that they know a fiction title can be promoted through, such as a Barnes & Noble newsletter, or an ad through Audible, or a review in the New York Times Book Review, so competition for the attention of book readers and larger entertainment-consuming audiences is fierce. A marketer not only needs to figure out how to make a book stand out from other books, they must also situate a book so that it (hopefully) doesn’t get ignored by a consumer in favor of other media, like television shows, movies, and more. Marketers have many audiences to consider and appeal to, all at once.

Marketing departments in publishing houses also have many authors to engage with, all at once, and the type of marketing that can be done for these authors varies greatly. This process can be the most difficult for debut authors, as they face not only a steep learning curve in regards to marketing practices, but also an uphill battle in becoming a known quantity to the world at large. Marketers are often starting from scratch in regards to promoting a debut fiction author, and creating a public persona for not only the author, but their work, takes a lot of focus, imagination, and persistent effort.

Former Tor.com staff writer Ryan Britt went through the struggle of being a debut author firsthand during the run-up to his first non-fiction book Luke Skywalker Can’t Read, which came out in November 2015, shortly before the debut of Star Wars: The Force Awakens. “What I really needed to focus on was persistence. I’ve worked in the publishing industry and I’ve worked on the floor in book retail before, so I’ve seen marketing from many sides, where it begins, how it’s executed, and how successful it is. And to create an awareness of a new author really takes persistence in all of these areas. A marketing person at a book publisher deals with lots of authors and is probably overworked, so you have to remind them that you’re there, but in a helpful way. Which means updating them on what progress you have made, and suggesting work that you can do to help with their marketing ideas. Your own persistence makes you an ongoing presence to your publisher and the marketing department, which may open up a larger number of venues for you to be presented within. And this all starts way before your book is even out.”

Getting a marketing department or a potential reader to pay attention to a debut author in the first place requires a lot of initial conceptual work, as well. Britt continues, “Making people aware of my book took a lot of imagining on our part, not only because we had to put me in front of an audience, but because we also had to figure who that audience was before we found them. It’s not as simple as just giving a copy of my book to every person in the 501st Stormtrooper Legion. They’re obviously a part of the audience for my book, but there’s also the millions outside of dedicated fandom who will go to see The Force Awakens and that will be the extent of their exposure to Star Wars. Where do you find them? What appeals to them?”

Marketing efforts are all about rapid, if not downright instant, communication to a consumer, and this shapes the message and format of the marketing for a debut fiction author’s work. When conceptualizing the audience for a new book, it’s important to focus on the concept and tone of the story, as potential readers will more rapidly trust a story that feels familiar, even if they don’t already know the author. So how can an advertisement immediately communicate a complex novel’s tone to its potential audience?

The differences in marketing that successfully communicates with its uncaptured audience can be ridiculously minute. For example, which of the below mock advertisements for Brian Staveley’s debut fantasy novel The Emperor’s Blades communicates the quickest, to the most receptive audience?

Not this one. This ad is too specific to people already familiar with Brian Staveley and his series. All the elements of the story and its tone are here, but they’re presented without context, so the ad ultimately says nothing.

This ad is too broad, attempting to appeal to too wide and generic an audience. In doing so it also loses the specific tone of Staveley’s work.

This ad is not ideal, but it’s the best of this purposefully-crummy lot. Although the slogan is passive and descriptive, not a direct call-to-action like “Come get a taste,” that passivity is nonetheless engaging and welcoming, which encourages a consumer to interpret it through their own reading preferences. If ninjas riding giant eagles is a concept that appeals to a consumer, then they may purchase the book to satisfy their curiosity. If ninjas riding giant eagles is a concept that sounds too silly to a consumer, the ad nonetheless makes an impression. Even though the ad hasn’t captured a new reader, that consumer will now be aware of the debut author if they see his name elsewhere.

While an author’s marketing efforts never really end, a publisher’s marketing efforts typically become focused in a six to nine-month window before the publication of a book. This allows the marketing team to determine what concept or message they will primarily promote about a book or author, then gives them time to procure reviews, ad space, retailer table space, and more. (Reviews and ad space typically have a three to six month turnaround, as reviewers need time to receive, read, and write about a book, and many outlets sell their ad space three months out.)

If the author and the publisher’s marketing department do their job well, then a reader who is initially completely unaware that a debut author’s book exists, is now both aware of and excited for that book to finally arrive on shelves. And if marketers do their job supernaturally well, then a reader is aware and excited for that debut author’s book solely by word-of-mouth, without having seen a single ad or review for it.

In terms of a publisher’s timeline, marketing plans are created around the same time that the manuscript and cover comes in. That marketing plan is executed around nine months before the release of the book.

How the marketing and advertisement process could be shortened for The Winds of Winter:

As the latest novel in an ongoing series, the bulk of the marketing has already been accomplished for The Winds of Winter. Readers are already well aware of A Song of Ice and Fire and anxious for the next book. The author is beyond celebrity, he’s damn near a meme unto himself. In cases like these, the persistence that debut authors must accomplish in order to create attention is flipped by fame. The public will pay persistent attention to George R. R. Martin even if he doesn’t want them to (and arguably, he’d prefer that the public not be paying so much attention to his progress on The Winds of Winter). The marketing department recognizes this familiarity and bases its work off of this public perception.

Even a book as long awaited as The Winds of Winter can’t be released without any new marketing push, though. Audiences for the book who aren’t considered “captured”—in essence, people who aren’t keeping track of the book’s progress on their own—may not realize a new Song of Ice and Fire book is out (especially considering the wealth of spin-off titles published in the last few years) unless ads, reviews, and coverage in mainstream news outlets are procured. That quick 30-second snippet on a local news channel or that five-minute FM radio interview with Martin doesn’t happen on its own. The marketing and publicity team arranged and scheduled that radio interview. The marketing and publicity team created the raw b-roll footage and pre-recorded interview answers that the news channel cut together.

Tallying up the physical assets that must be assembled for marketing efforts can give a reader some idea of the time and complexity involved in marketing work. The publisher’s marketing team wrote interview questions, shot and produced a series of videos, and a news channel reformatted that material into a new video segment, all for a chance that an “uncaptured” casual reader will see the author or book during the 30-second window that it appears on television. Because media coverage for a single product is so widespread, it may seem homogenous (and it is, because it’s promoting an isolated concept instead of a multi-faceted issue), but getting coverage to such a widespread point isn’t easy, and it takes an unavoidable amount of time. This kind of production of marketing material can (and has) been accomplished in a three month window, but it takes a truly ceaseless amount of work, and this impacts work that marketers would otherwise be doing on other titles.

A three-month marketing window also negatively affects “captured” audiences. As Theresa DeLucci, Tor Books Associate Director of Ad Promo, points out, “Even with a dedicated readership, a book series’ sales typically go down as that series continues. The first book always sells the most. So when a new volume comes out, this changes the information that you need to communicate to that audience. It’s not so much about notifying them that the book exists—they’re already interested—it’s about communicating that it’s time to return to the world of the series, that the new book will expand that world. In some cases this means promoting the new book as a ‘return to form’.”

A reader familiar with a book series may feel comforted that a new book is a “return to form,” but that reader also knows that a publisher isn’t going to criticize its product, so marketers anticipate the reader’s need for a genuine appraisal of the book by giving independent book reviewers time to read the book and offer their external, unbiased opinion. A favorable review from a major outlet like Time or The New York Times is extremely valuable to a publisher’s marketing efforts in this regard. The Winds of Winter‘s short turnaround time makes receiving these reviews difficult to procure. The book can only be sent to a handful of outlets, for one, due to the secrecy surrounding the plot, and the security needed for that kind of secrecy slows down the review process. A slowed-down review process means the publisher’s marketing efforts may go without favorable third-party claims, which severely limits what it can say to established readers and fans of A Song of Ice and Fire.

Marketing for a legacy series like A Song of Ice and Fire can still be accomplished in three months, for the most part, it just means a more extreme and more vague promotional process. What can’t be accomplished through reviews and word-of-mouth can be compensated for by basic blanket coverage of the book’s existence. Marketing The Winds of Winter in only three months wouldn’t be informative, but it would definitely be possible.

Book Production, Step Four: Selling the Book to Booksellers

A little-known fact among readers is that bookstores do not automatically carry every new book published. Every month, booksellers carefully choose the new releases that they believe they can sell, even amongst the offerings of the largest book publisher (Random House, the parent company of George R. R. Martin’s U.S. publisher Bantam). Book publishers present their forthcoming books during a Sales process in which upcoming books are pitched with covers, marketing plans, and projected sales numbers to booksellers and distributors. The more books that sellers choose to stock from a publisher, the larger that publisher’s market share gets, the more their profits increase, and the more debut authors they can take a chance on.

Although a sales pitch brings together a wealth of information and work accomplished by the editorial, art, and marketing departments, the pitch is only the beginning of the sales process. The ensuing sales process bridges the gap between the editing and marketing of a book and the eventual printing of that book. This work is mathematical, analytical, and personal. This is where real number-crunching and negotiating skills come into the book production process.

The sales process begins around seven months before a season (book publishing splits the year into two or three seasons of roughly equal-length) when a publisher’s sales representative pitches the next season’s books to each retailer and distributor’s “buyer.” The job of the buyer is just what it sounds like: they are the person or department that buys books to stock in their company’s stores. (Barnes & Noble’s science fiction and fantasy buyer is a man by the name of Jim Killen. Disclosure: He also curates a list of particularly notable monthly releases in those genres which Tor.com features on its website in conjunction with the B&N blog.) The constant fine-tuning that occurs during the sales process means that rep and buyer keep in constant contact.

Using materials created by the marketing and publicity departments (which are themselves building off the editorial and cover art processes), the publisher sales rep pitches the next season of books to the buyer, along with preliminary sales estimates for those books based on analysis of the current market, the author’s public status, and previous sales history. A buyer then comes back with an order for the books that specifies how many copies the buyer thinks they can sell of each book. This is an important initial number, as it is combined with the initial orders from all the other buyers and used as a baseline for how many books the publisher will have to spend money printing in the next season.

The rep and buyer will go back and forth to finalize the number of books ordered. The rep may point out that an estimate for a debut author is too low, as the publisher has signed them up to a major 5-book deal (which means that the publisher is going to spend significant resources marketing the books to see a return on the investment). Or the rep may point out that an author is about to be featured on new hit reality show Stranded on Cannibal Island, so the buyer should make a big initial order on that author’s book. The buyer may counter that if the reality show is a hit then it will want the publisher to add a sticker or blazon to the cover which mentions the reality show, otherwise they won’t increase their buy estimate. Once the sales rep and buyer are satisfied that all details regarding an upcoming book are being taken into account, the order is finalized, price points and discount periods are set, the book can now go on sale for pre-orders, and a firm release date* can be announced!

*A note on release dates: It is standard for a book’s release date to change several times. A publisher first assigns a season it expects the book to be out in, then once the book is turned in, or close to being turned in, a hoped-for release date is assigned. This is what gets used during the sales process and is often what you see initially in a retailer’s online listing. That release date then shifts around depending on the status of a book’s production (as we’ve seen repeatedly with The Winds of Winter) as well as to avoid potential competitors among other book releases (You probably don’t want to release a Joe Hill novel on the same day that his father, Stephen King, has a book coming out, for example.)

The buyer’s estimate changes constantly in the months leading up to printing, distribution, and release of a book. This is based off of the retailer’s own internal information and analysis (“This book has been coming up a lot in info desk database queries.”) as well as updates from a publisher’s rep. (“The author got eaten on Cannibal Island so we’re going to switch back to the regular cover. You should minimize your buy estimate accordingly.”) Pre-order numbers are also used to adjust a buyer’s numbers. If pre-orders are weak, a buyer may lower their estimate, if the pre-orders are stronger than expected, a buyer may raise their estimate. (So if you have a friend putting out their first novel soon, pre-ordering actually does help them quite a bit.) A publisher’s sales rep may or may not fight this adjustment based on pre-order numbers, as publishers have a unique incentive to get as close as possible to the exact number of books that will sell: any book a vendor like Amazon, your local bookstore, or Barnes & Noble doesn’t sell is returnable to the publisher for credit on future purchases. This is a cost that publishers shoulder entirely, so their desire is to minimize the number of books that get returned.

How the sales process could be shortened for The Winds of Winter:

The sales process is started seven to nine months before a book’s hoped-for release, but it doesn’t necessarily take that long. The Winds of Winter doesn’t need to be pitched to a buyer—just confirmed. It also doesn’t need to be tied to a particular publishing season; its anticipated popularity is such that it will do well regardless of its release window or competition. Every buyer’s order will essentially boil down to “A LOT,” so a sales rep’s job on The Winds of Winter will consist mostly of working out which vendors get how many copies, and how much Bantam will initially spend printing the massive stock of the U.S. version of the book.

It is also very likely that the buyer estimates are already worked out, since Martin mentions in his update that his U.S. and overseas publishers had set a Halloween and New Year’s deadline. That they were able to shift the deadline to New Year’s at all implies that a lot of the preparatory work, like the sales process, had already begun.

There’s an interesting wrinkle that a popular book like The Winds of Winter adds to the sales process, though. When requesting series books that are guaranteed bestsellers, buyers will often ask for very high numbers of copies in their buying estimates; higher than the sales of the previous book in the series, even though sales actually go down in a series over time. Overstocking a popular book in this manner benefits the retailers and vendors because it allows them to offer a deeper release-day discount than other vendors. For example, if a bookstore chain knows it will sell 100,000 copies of the $35 edition of The Winds of Winter, then they know they will safely make 3.5 million off of the book at cover price. If they want to offer the book at an initial 30% discount, though, then they’ll shift their buy estimate up to 142,858 copies so that they still bring in 3.5 million. Both approaches bring in the same amount of money, but the approach that buys 142,858 copies has an added benefit in that the bookseller gets to offer a deep discount on the release day that no one else may be able to match. Since so many outlets will be selling The Winds of Winter, it is small advantages like this that could make a retailer the preferred business for consumers to buy the book from, and since unsold books are returnable to the publisher for future credit, manipulating a buy estimate in this manner poses no risk to the buyer.

Buy estimate manipulation can lead to some interesting consequences for publishers. Amazon.com’s discounts are so famously deep that independent bookstores sometimes find it cheaper to buy stock from Amazon.com at their discounted retail price rather than buy stock at the publisher’s wholesale price. Publisher sales reps can try and avert inflated buyer estimates by keeping with a series author’s previous sales performance to avoid this kind of overstocking, as well as to prevent a product from being flooded into the market and becoming quickly devalued. The Winds of Winter is in a unique position when compared to the circumstances surrounding the release of A Dance With Dragons, though. While Winter will benefit from Game of Thrones‘ established presence and massive popularity, it will also be competing with the show in regards to story revelations and fan backlash over the delay of the book. Even though series get less popular over time, the initial sales numbers for Winter may very well be higher than Dance, which may make preventing overstocking somewhat difficult.

Book Production, Step Five: Formatting and Finalizing

Let’s make a book.

Once a book is edited and sold, it now must be crafted into a format that a printing press can easily duplicate. The general term for this process is called typesetting and is handled by a publisher’s book production team, who may contract the job out to independent typesetting production houses depending on the volume of books they’re working on that season. Typesetting begins around the same time that copy editing begins on the manuscript and takes two to six weeks to accomplish.

Why so long? The typesetting process is extremely granular, well beyond the capabilities of word processing programs like Microsoft Word, as it involves placing and adjusting text-as-object on a page while ensuring continuity in design and content from page to page. Within that, the typography of the text itself must be gone over with precision in order to ensure uniform spacing between characters (known as kerning), uniform spacing between groupings of characters (known as letterspacing), and uniform spacing between lines of text (known as leading), while creating pages with text that are justified to the page’s blank margins without being stretched. Typographical adjustments such as this (and many MANY more, this description only scratches the surface) must be made throughout the entire book, letter by letter. Often there are design and typographical standards, house styles, and more already in place for novels and established series, but even with those in place the act of poring over a text so precisely still takes time.

There are also non-text design elements to incorporate while typesetting, such as text borders, chapter heading icons, introductory materials, and one of the most beloved fantasy novel elements: maps!

A typeset manuscript is a vital tool for all the departments involved in the creation of a book, from the author to sales, but while most departments can still proceed with their work without a typeset manuscript, a printing press requires a typeset manuscript, not only so there’s a file to print from, but because typesetting determines the page count of a book.

The page count determines how much paper a publisher will ask for in the forecast that the publisher will send to the printing press. Forecasts are made on a monthly basis, and since paper type varies from book to book these forecasts need to be precise in order to avoid spending extra money on paper the publisher may not be able to utilize on other books. When you’re publishing hundreds, if not thousands, of new titles per year, this wasted paper can pile up quickly.

A page count is also needed for determining the number of plates and sheets needed per book. Printing plates, and the sheets they print onto, can fit 16 book pages. Because of this, books are typeset to produce a page count as close as possible to a multiple of 16. A book that is precisely 800 pages long will fully fill 50 sheets. A book that is 812 pages long will fill 51 sheets, but since 812 is four pages less than the next multiple of 16, that means the final book will have four blank pages at the very end. Publishers try to minimize the number of these blanks as much as possible and more than three or four is considered unacceptable.

The typesetting period in book production is a flurry of finalizing activity. Copy edits get incorporated into the typeset, and a series of drafts are produced for the editor to review. For most books, a copy of the typeset is also sent to an independent reviewer, preferably one familiar with the world that the book is set within, as a safeguard against the tunnel vision that authors, editors, and publishers can develop when working and reworking a book. Independent reviewers often catch typos and small continuity errors and are a big help in further solidifying the text of a book. More corrections get made to the text in the typeset and a First Pass manuscript becomes a Second Pass. At this point, no large edits can be made to the manuscript, although exceptions have occurred. Jim Kapp, Senior Production Manager at Macmillan explains how the production process compensates for a substantial emergency edit: “If a half-page needs to be struck out, the author will be asked to provide another half a page of content in order to keep the pagination intact.”

Maps and chapter art are finalized at the same time that all edits are incorporated. Once the typeset manuscript is ready, the editor signs off on it and the Production Manager sends the files off to the press. This is the point of no return (at least until a book goes into a second printing) in regards to changing any of the book’s content.

The typesetting and finalization process is intense and fluid, and can take up a wide range of time depending on the book, from two weeks to several months.

How the formatting and finalization process could be shortened for The Winds of Winter:

A publisher can hasten the typesetting process for a book like The Winds of Winter by increasing its production budget temporarily. Typesetting, although detailed, is still comparing a manuscript to a single established standard, so the work can be split among a team of typesetters, or even an entire company. An outside reader can be skipped, or utilized for a second printing, if the author and editor feel they aren’t immediately vital. (It has been the trend in the past few decades for best-selling fantasy authors to not skip this step, however. In fact, established authors tend to put more effort into curating teams of beta readers as their work progresses. For more on the process, check out Alice Arneson’s article on her experience beta-reading Brandon Sanderson’s Words of Radiance.)

Since The Winds of Winter is part of an established series, there is already an established template to plug the manuscript into, and even though the manuscript isn’t completed, the publisher can provide a forecast for the amount of paper based both on minimum page counts from previous books in the series and via communication from George R. R. Martin on the standing word count. Winter will likely be similar in length to A Storm of Swords and A Dance With Dragons, which means that the publisher will want to order paper sheets that will produce between 960 (60 sheets) and 1088 pages (68 sheets) per book. 68 sheets is the maximum size a hardcover volume can achieve, as book printing presses aren’t built to print and bind thicker volumes. (Brandon Sanderson’s Words of Radiance took some fancy production footwork so it could be squeezed onto 68 sheets, as did Patrick Rothfuss’ The Wise Man’s Fear.) Since The Winds of Winter is printed on fairly standard hardcover paper stock, Martin’s publisher could specify 68 sheets per book, then use the leftover paper for other books it needs printed. Since Winter is guaranteed to have a high print run, making a forecast that overestimates the page count would leave a lot of leftover sheets. Since that paper can be re-used, purchasing more paper than needed for The Winds of Winter would mean that the publisher is essentially buying two books worth of printing paper for the price of one.

Since the typeset process can take place in parallel with the copy edit process (which can take place nearly in parallel with the line edit process), much of the formatting and finalization of The Winds of Winter book can be compressed into a very small time frame, adding only a week to the overall production process for the book.

Book Production, Step Six: Printing and Distribution

The economics of printing presses are similar in concept to airplanes: if they’re not moving then they’re not making money. This economic reality creates competition among presses to be the company that can produce a publisher’s order as quickly as possible. Thanks to decades of innovation in physical and digital printing techniques, presses in the 21st century are able to produce large quantities of books very quickly. A single black-and-white printer can produce 22 miles of 16-page sheets in one hour. This translates to over 300,000 book pages in an hour from only a single printer in the press, so a press with 50 printers could print 360,000 1000-page books in one 24-hour day! This is literally too fast for the paper-feeding, binding, quality assurance, and boxing processes that come before and after the printing itself, so these numbers do not represent the actual speed of printing press companies. They are just a demonstration of how drastically the potential speed of printing has been increased in recent years.

The entire process of printing a book the size of The Winds of Winter and in the amount that need to be shipped to booksellers still takes about two to three weeks. To find out about the entire process, take a look at this step-by-step rundown of the printing of another enormous fantasy blockbuster, Robert Jordan and Brandon Sanderson’s A Memory of Light.

(Note: Alongside the text, the cover jacket is also formatted and printed. This is a separate process that you can see chronicled here.)

The publisher has a “bound book” date that it gives to printing presses in regards to when they want all copies of the book printed. Many, if not all, printing press companies also handle the distribution of the boxed and completed copies of the book, so publishers also request a “release date” from the printing press company, so that they know when the printing press has shipped all copies to the publisher’s warehouse. The term “release date” can be misleading in this regard, as it doesn’t stand for the day that the book is put on shelves but rather the day that the printed books are “released” from the press to the publisher.

A publisher’s distribution network takes over from this point, trucking the books from the publisher’s warehouse to the various distribution warehouses of retailers like Barnes & Noble and Target. Those distributors then parcel their stock out to their individual stores.

A single bookstore receives several pallets of books to stock per day from its distribution warehouse. Huge releases like The Winds of Winter (or a Harry Potter book) come in specially marked boxes with the on-sale date stamped on them. For brick-and-mortar retailers, these boxes are considered embargoed, and aren’t even opened until the morning of the on-sale date, just before the store opens.

This multi-step distribution network may look as if it takes a lot of time, but it’s surprisingly short when you take weekends and 24-hour shipping timelines into account. Additionally, printing presses that handle non-color books, like novels, are mostly based in the U.S., which cuts down on time needed to ship printed copies of The Winds of Winter from overseas. Stock can be transferred from the printing press to the publisher warehouse in a day, and round-the-clock trucking routes and freight airlines don’t take more than two days to deliver the books from the publisher warehouse to the retailer warehouses. Tack on another day for stores to receive their allotment of The Winds of Winter and the complete time-frame for distribution becomes clear: three to four days. New books are always released on a Tuesday in the U.S. (or Monday at midnight for high profile releases like The Winds of Winter), so a printing press company can finish printing books the Thursday before to have a title in stores on time.

How the printing and distribution process could be shortened for The Winds of Winter:

Not much changes, here. Publishers would pay the printing press company a rush fee to prioritize the immediate printing of The Winds of Winter, but otherwise the time frame is largely the same. If they wanted to, they could split up the printing between several companies and shrink the total turnaround time to just seven days, but that’s one hell of an expense to shrink this process from 16 days to 7. At that point you’re only shaving off a single week.

How Much Time Could The Winds of Winter Take?

My speculation on the production of The Winds of Winter, mapped out into three months:

A larger version of the graphic can be viewed here.

Why Isn’t Every Book Published This Quickly?

If any novel, especially eagerly awaited novels in fantasy series, could be published only three months after the manuscript is turned in, then why aren’t new books always turned around this quickly?

What may not be apparent is that rushing a book out this quickly requires the attention of entire marketing and production teams, as well as the uninterrupted attention of the book’s editor. This means that these teams and editors cannot work on other books that, while they may not sell as massively, are undoubtedly just as worthy in the eyes of the authors, editors, and readers who champion them. A year-long production cycle gives editors, marketers, and formatters time to focus on several new titles at once, which ensures a wide variety of new books per year, whereas a three-month production cycle only ensures the publication of a single book every three months. Many can create one, or many can create many.

“Many creating many” is the model that best suits the ongoing creation of literature. This is how publishers and editors have the time to bring new authors to light. This is how it becomes possible for a reader to find that one book that reverberates thunderously within their soul. This is how we keep literature vibrant.

Sometimes it is absolutely worth it for many to create just one, like The Winds of Winter. While rushing a book out in a three-month time frame is incredibly expensive in terms of money and time spent, proven bestselling commodities like George R. R. Martin’s Song of Ice and Fire series are justified in this practice because they make it financially possible for publishers to take a chance on brand new authors. Those three months spent supporting only a single author make it possible for publishers to afterwards support many authors.

The important thing is, of course, balance between the two practices. When that balance is struck perfectly, everyone benefits and we all enjoy an ideal environment of good books, lots of them, as soon as possible.

Chris Lough is the Content Director of Tor.com and covers the epic fantasy genre for the site. You can find him on Twitter, or peruse his wilier works on his website.

“Manuscript” by Seth Sawyers, used under Creative Commons. Source.

“Dr. Robert H. Goddard at a blackboard at Clark University in Worcester, Massachusetts, in 1924.” Author: NASA. Public domain. Image modified for this piece.

Willi Heidelbach photo of metal movable type used and modified under Creative Commons. Source.

Images of Julie Bell and printing press by Irene Gallo, used with permission.

Correction 1/14: The paragraph referencing the Winds of Winter cover art originally read “Although we don’t know what the cover for The Winds of Winter will be, the fan mock-up cover pictured here follows the same template. While this mock-up is the work of a fan and was not designed by the publisher, it nevertheless follows the design template of the series and looks legitimate enough that Martin himself used it in his January 2, 2016 update about the book.” The author has clarified that the cover art in question is publisher-based. This article has been updated to reflect this.

Postscript: I created my own Winds of Winter cover mock-up for an earlier version of this article, but aside from the cropped image at the top of this article, there was no place for it. If you’re curious what it looks like, here’s the full version:

And here’s a less snowy version: