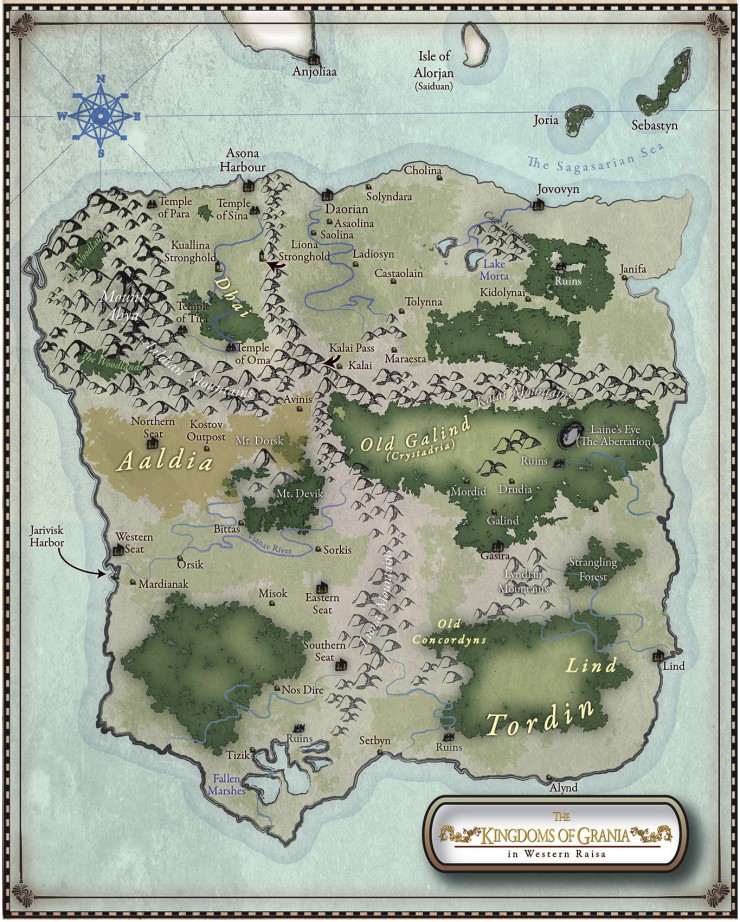

Every two thousand years, the dark star Oma appears in the sky, bringing with it a tide of death and destruction. And those who survive must contend with friends and enemies newly imbued with violent powers. The kingdom of Saiduan already lies in ruin, decimated by invaders from another world who share the faces of those they seek to destroy.

Now the nation of Dhai is under siege by the same force. Their only hope for survival lies in the hands of an illegitimate ruler and a scullery maid with a powerful – but unpredictable –magic. As the foreign Empire spreads across the world like a disease, one of their former allies takes up her Empress’s sword again to unseat them, and two enslaved scholars begin a treacherous journey home with a long-lost secret that they hope is the key to the Empire’s undoing.

But when the enemy shares your own face, who can be trusted?

In this devastating sequel to The Mirror Empire, Kameron Hurley transports us back to a land of blood mages and sentient plants, dark magic, and warfare on a scale that spans worlds. Read an excerpt from Empire Ascendant—available October 6th from Angry Robot.

PROLOGUE

“The body’s here.”

Kirana Javia, Empress of Dhai, Divine Kai of the Tai Mora, gazed across a field of corpses. She gnawed at a wizened apple, pausing only to pick a fat worm from its center and flick it over the railing of the thorny broken tower she stood upon. The sky was an amber-bronze wash; it always looked like it was on fire. The blackened husk that had once been the heavenly star Para glowed red-black. It turned the light of the double suns a malevolent orange, and the tiny third sun, Mora, was no longer visible. Below, her omajistas and their handlers went body to body, gutting the deceased and collecting their blood into massive clay urns. The first few years of the Great War, Kirana had commissioned glass jars, but they broke easily, and worse – seeing the blood carted off hurt her army’s morale. It reminded her people of what they were doing – bleeding out a sea of dead to save the living. You could measure the number of dead now by how many urns left the field. Carts stuffed with urns stretched across the muddy ground so far she lost sight of them in the woodlands beyond. If the infused mirror that could keep the way open between worlds had not been sabotaged, these people would still be alive, running after her army into a new world. But now she was back to killing and collecting. She told herself the deaths weren’t wasted, merely transformed. This close to the end, nothing could be wasted.

She popped the apple core into her mouth and turned.

Two soldiers in tattered coats stood at attention. The slashed violet circles on their lapels marked them as lower-level sinajistas, one of the more expendable jista castes, as their star wouldn’t be ascendant for another year, and this world would be dead by then. Their black hair was braided into intricate spirals and pinned in place. Hunger sharpened their faces into a grim severity. Kirana longed for the days when every face she saw was some jolly fat parody of itself. Even my own people look like corpses, she mused. How appropriate.

The soldiers carried a large brown sack between them, stained dark with blood and – from the smell – the remains of a voided bowel.

“What a lovely gift,” Kirana said. She trotted down the steps to join them. The turret room was a ruin, like most of the buildings they occupied in these final days of the routing of the world. Many knew they were coming, so they burned, broke, or poisoned anything of use before her people arrived. The furniture was smashed, and the resulting kindling burned. Kirana had found a shattered mirror near the door and used a fragment to dig out an arrow head that had pierced through a seam of her armor. The armor still bled where it’d been struck. It would take hours to repair itself. She rubbed at the sticky sap on her fingers.

The soldiers yanked at the cord that bound the body in the bag, spilling the contents.

Kirana leaned over for a better look. Tangled black curls, round face, straight nose.

“It’s not her,” Kirana said, and she could not keep the disappointment from her voice. “Not even close. Are you just picking up random bodies and carting them over?”

The taller soldier winced. “They all look alike.”

Kirana sneered. “The only face that looks like yours in that world is your double’s, and I can tell you now that you’ll never meet them as long as you’re living. If you can’t do this one thing I’ll–”

The body on the floor stirred.

A stab of pain splintered up Kirana’s leg. She hissed and jumped back. The formerly dead woman yanked a knife from Kirana’s thigh and leapt up, spitting green bile. She slashed at Kirana again and darted between the two startled sinajistas.

Kirana lunged after her, making a wild left hook. The woman dodged and bolted out the door – a shocking turn of events if she wanted Kirana dead. Who would send an assassin after Kirana that broke away so quickly? Unless Kirana wasn’t the target.

“She’s after the consort!” Kirana yelled, and sprinted after her.

The assassin was fast for a woman recently dead. Kirana saw the curve of her ass disappearing down the far corridor. Kirana went after her, sliding as she rounded the same corner. Her boots were losing their tread. The assassin huffed herself from the top of the stair down to the landing. Kirana jumped the curve of the banister after her, relying on her armor to cushion the fall. The assassin wasn’t running blind. She was making her way directly to the quarters of Kirana’s consort and children.

Some other world had found them. Someone was coming for them.

Kirana jumped over the next curve in the stair and collided with the rail below her. It took the breath from her. She gasped and heaved forward, reaching for the assassin’s bare ankle. She got a kick in the face instead. Kirana scrambled up and moved down the long hall. Now that they were clear of the stairs, she shook her wrist, and the twisted willowthorn branch nestled inside her arm snarled free, snapped out.

She slashed, searing the woman’s long tunic. The fabric fell away, hissing and smoking.

They were three doors from her consort’s rooms. Kirana put on a burst of speed. She jumped and lunged, thrusting her weapon ahead of her, as far as she could reach.

The willowthorn sword rammed into the assassin’s hip, drawing blood. Kirana hit the ground hard just as the assassin did. They came together in a snarl of arms and legs. Kirana climbed over her. Thrust again. The assassin caught her arm and bit her wrist. She flipped Kirana over neatly, as if she weighed nothing. Kirana headbutted her in the face. The assassin’s nose popped like a fruit, spraying blood. Kirana stabbed her twice in the torso and kicked her off.

The assassin hit the floor and continued trying to scramble forward, sliding in her own blood.

The sinajistas finally caught up with them. They grabbed for the assassin. Kirana knew restraint wasn’t going to work.

“Take her head off!” Kirana yelled. They were tangling with the assassin. She was a tireless ball of sinew and flesh brought back to life by Sina alone knew what.

Kirana pushed to her feet and took her weapon in both hands and swung. She caught the assassin in the jaw, ripping it free of the face. She hacked again, opening up the throat. The sinajistas dropped the body, and Kirana finished it, detaching the head from the neck while the widening pool of blood licked her boots. She bent over, trying to catch her breath. The body still twitched.

“Burn it,” Kirana said. She clutched at a pain in her side; she had overstretched or torn something. She winced and straightened as one of the sinajistas went back upstairs to collect the bag for the body. A handful of the house guards she had put in charge of the hold came up now too, full of questions. She’d deal with them later.

Kirana limped down to her consort’s door and knocked heavily.

“It’s the Kai,” she said. “Are you all right?”

The door opened. She must have been listening to the scuffle in the hall. Yisaoh stood just over the threshold. Her scarlet robe brushed the floor. She was medium height, broad, her dark hair twisted into a knot on top of her head. Her nose was crooked, broken twice during her very long apprenticeship in the army before Kirana signed her discharge papers.

Kirana leaned into her, spent. She pressed her face to Yisaoh’s neck and breathed in the scent of her.

“Are you safe?”

Yisaoh pressed her hands to Kirana’s hair. “This blood–”

“Not mine,” Kirana said. She raised her head and searched Yisaoh’s face. “You’re all right? Where are the children?” She moved past Yisaoh, heading toward the nursery.

“They’re fine, love,” Yisaoh said. “There’s a storm coming, the stargazers say. We need to close everything up.”

Kirana crossed the sitting room, stumbling over a heavy piece of furniture. The room was mostly in order, though a few things were still overturned. She had had these quarters meticulously searched and set up for her family the moment the siege ended.

She opened the door to the nursery, weapon up. The children slept together in a big bed at her right. The room had no windows, making it a safe refuge from the storms. Kirana counted their three perfect heads.

Yisaoh placed a hand on Kirana’s shoulder. She flinched.

“I gave them a draft,” Yisaoh said softly. “They were up all night in camp during the siege, worrying over you. They needed to sleep.”

The weapon in Kirana’s hand softened. She released it, and it snaked back into her wrist. She let out a breath.

A low, insistent bell clanged outside. The familiar three-by-two-by-three gong that warned of a dust storm.

“Stay here with us, you fool,” Yisaoh said. She shut the door behind them, sealing all of them into the quiet black of the children’s room. She rummaged around in the dark and took hold of some kind of rustling fabric.

Kirana watched her stuff it under the seam of the door, muffling the last of the light. The dull moan of the bell changed, muted by the change in air pressure.

Yisaoh grabbed Kirana’s hand and pulled her down beside her in the darkness. Pain stitched up Kirana’s leg, and she hissed. She had almost forgotten about the wound.

“Are you hurt?” Yisaoh asked. “Oma’s eye, Kirana, I’ve sewn your limbs back on and seen you with half your face torn away. Don’t hide an injury from me.”

They pressed against one another. Kirana’s breath sounded loud in her ears. She was still filled with adrenaline, ready to leap at shadows. The storm hit the hold. The stones trembled. Air hissed between the seams of the stones, and Kirana smelled the dry apricot breath of the black wind kicked up by their dying star. Getting caught exposed in storms like this could rip flesh from bone, and fill one’s lungs with rot.

“Kirana?” Yisaoh again.”I will sew your seat in place if you don’t tell me if –”

Kirana took a lock of Yisaoh’s hair in her fingers, and felt a pang of love and regret. Love for a woman she had conquered three countries to save from a fractious rival, and regret that she was so devoted to a single soul that she could not leave this dying world unless she had this woman by her side. The wind moaned through the hold.

“I’m fine,” Kirana said. “We’ll find her soon. You will all come with me to the new world.”

“This is the second person she’s sent to kill you,” Yisaoh said. “That other woman, that other me, she is ruthless. She will not stop.”

Kirana did not correct her, did not say the assassin had cared little for Kirana, and run straight here for Yisaoh. “We don’t know it’s her. There are half a hundred worlds with–”

“It’s her,” Yisaoh said, and the certainty in her voice chilled Kirana. “It’s what I would have done, if you had sent people to kill me.”

Kirana pressed her fingers to the wound in her leg where the assassin had stabbed her. The armor had already sealed itself with sticky sap. The sap had closed the wound inside, too, or at least stopped it from bleeding. She would need to see a doctor soon. Poison was a possibility.

“You tell me they have no armies there,” Yisaoh said, her voice barely audible now above the wind buffeting the hold. Kirana wondered when they would get the worst of it.

“No armies,” Kirana said, “but they aren’t complete fools. Not all of them. Little groups of people like the Dhai survive by being clever. I suspect she’s as clever as you, and that does make her dangerous.”

Yisaoh wrapped her arms around Kirana. It was awkward, with Kirana in full armor. Yisaoh’s robe was crushed velvet, soft, but beneath, Yisaoh was all knobby bones and cold flesh. “You remember when I was plump?” Yisaoh said. Yisaoh never did like it when Kirana reminded her about what it was that made her so effective in the army – her ruthlessness, her cleverness. Yisaoh had given all that up to rear their children. She was tired of torture and death. But the past followed them, relentless as the burning star in the sky.

“I remember,” Kirana said. She felt a stab of loss, as if she’d failed Yisaoh. Failed them all. Her stomach growled in answer. The apple was the first thing she’d eaten all day. “This isn’t over yet. If they hadn’t broken the mirror I’d have sent every one of my legions after her. They have wards on her, so I’ll send a ward-breaker this time, and take her head for good measure. Then you and I will cross over and–”

Yisaoh pressed her fingers to Kirana’s lips. Kirana remembered the day they had met. Yisaoh had emerged from the warm waters of the Shadow Sea, brown-gold and beaming at some shared joke between her and her companions. Kirana had stood on a low rise above the rocky beach, and had been struck dumb by the sight of her. Kirana was bleeding out from some wound inflicted in a minor skirmish over the next hill. Isolated on the little beach amid the pounding surf, Yisaoh and her companions had not heard the fighting. It was like stumbling into some forgotten world, like Kirana’s bright childhood, carefree, before the sky imploded. Before the world began to die.

The wind wailed. The children stirred. Kirana listened to the sound of her own heartbeat begin to tick down. Surely she would have felt the poison by now, if it was a poisoned blade? She had to admire the act – the forethought to hire a lookalike good with a weapon, one not afraid to feign death through drugs or some gifted trick, and hurl herself into some other world to murder Kirana’s family. It was a bold move for a supposed pacifist.

“I’m afraid,” Yisaoh said.

“I’ll take care of you.”

“No,” Yisaoh said. “I’m afraid of what we’ve had to become to survive this.”

“We can go back,” Kirana said. “When this is over–”

“I don’t think we can.”

Outside, the contaminated remnants of the dead star rained death and fire over the northern parts of the world. Kirana knew it would not be long now before it reached them here. Six months, a year, and the rest of the globe would be a fiery wasteland. The toxic storms blowing in the waste from the north were just the start of the end. If she had not murdered all the people she needed to fuel the winks between worlds, they would have died eventually. She was doing them a favor. Every last bloody one of them.

“Promise you’ll take the children,” Yisaoh said, “even if–”

“I won’t leave without you.”

“Promise.”

“I’ll save us all,” Kirana said. “I promise you that.”

Sitting there in the dark, holding Yisaoh while her children slept and her leg throbbed and the wind howled around them, she decided it was time to begin the invasion of Dhai in earnest. She had been waiting for the right time, waiting until they had enough blood, until they had rebuilt enough resources after the mirror’s destruction. But she was out of time. The days were no longer numbered. The days were over.

She held onto Yisaoh, and imagined walking into the great Dhai temple to Oma, Yisaoh at her arm, her children beside her, and her people spread out all across the plateau, cheering her name, calling her savior, already forgetting the atrocities they had had to commit to see that end. It was a vision she had nurtured now for almost a decade.

It was time to see it through.

1

Lilia did not believe in miracles outside of history books, but she was beginning to believe in her own power, and that was a more frightening thing to believe in. Now she sat on the edge of the Liona Stronghold’s parapet as an icy wind threatened to unseat her. She had spent over a week here in Liona, waiting on the Kai and his judgment. Would he throw her back into slavery in the east? She imagined what it would be like to topple from such a great height now and avoid that fate, and trembled with the memory of being pushed from such a distance just six months before, and broken on the ground below. The memory was so powerful it made her nauseous, and she crawled back down behind the parapet, head bowed, breathing deeply to keep from vomiting. Climbing was a slow business, as her clawed right hand still wouldn’t close properly, and her twisted left foot throbbed in the cold weather. Her awkward gait had only grown more cumbersome over the last year.

Dawn’s tremulous fingers embraced the sky. She squinted as the hourglass of the double suns moved above the jagged mountain range that made up the eastern horizon. The heat of the suns soothed her troubled thoughts. The satellite called Para already burned brilliant blue in the western sky, turning the horizon dark turquoise. Blue shadows purled across the jagged stone mountains that hugged Liona, festooning the trees and tickling at clumps of forgotten snow. She wasn’t ready for spring. With spring came the thawing of the harbor, and worse – the thawing of the harbors in Saiduan that held the Tai Mora, the invaders that would swallow the world country by country.

“Li?” Her friend Gian walked across the parapet toward Lilia, hugging herself for warmth. “Your Saiduan friend got into a fight, and said it was important for me to fetch you.”

Gian wore the same tattered jacket she had in the Dorinah slave camps. Most of the refugees who’d come over from Dorinah with Lilia’s ragtag band had been fed by the militia in Liona, but not clothed properly or seen by a doctor.

Lilia said, “Wasn’t it Taigan who insisted we stay out of trouble?”

“What do you expect from a Saiduan assassin, one of those sanisi? They are always fighting.”

Lilia thought she could say the same about Dorinahs like Gian, but refrained. She didn’t like reminding herself that Gian’s loyalties had first lain with Dorinah. Lilia held out a hand. Gian took it. Lilia sagged against her.

“Are you ill?” Gian asked.

Lilia gazed into Gian’s handsome, concerned face, then away. She still reminded Lilia too strongly of another Gian, one long dead for a cause Lilia didn’t believe in. Lilia wondered often if she’d made the wrong choice in not joining with the other Gian’s people. What difference would saving six hundred slaves make if the country was overwhelmed by some foreign people from another world? Very little.

“You should eat,” Gian said, “after we find Taigan. Let me help you.”

Lilia took Gian’s arm and descended into the teeming chaos of Liona. Red-skirted militia bustled through the halls, carrying bundles of linen, sacks of rice, and messages bound in leather cases. Dead sparrows littered the hallways, expired after delivering messages to and from the surrounding clans about the influx of refugees. Lilia had never seen so many sparrows. She wondered if the messages getting ferried around were about more than refugees. She’d been gone for nearly a year. A lot could have changed.

Milling among the militia were Lilia’s fellow refugees, often gathered in clusters outside storage rooms or shared privies. Lilia saw militia herding refugees back into their rooms like chattel, and bit back her annoyance. She wanted to send out a simmering wave of flame in their direction, boiling the offensive militia from the inside out. Her own skin warmed, briefly, and she saw a puff of red mist seep from her pores. The compulsion shocked and shamed her. Some days she felt more mad than gifted.

Omajista. The word still tasted bad. A word from a storybook. Someone with great power. Everything she felt she was not. But she could draw on Oma’s power now. Omajista was the only word that fit.

Lilia kept her arm hooked in Gian’s as she limped down the hall. Her hand hadn’t been the only thing twisted in her fall, and even before that, her gnarled left foot had made walking more difficult for her than others. She felt eyes on her even now. What did she look like to them? Some scarred, half-starved, misshapen lunatic, probably. And maybe she was. She opened her left fist, and saw a purl of red mist escape it. What did it feel like to go mad? They’d exiled gifted people for going mad with power, like the Kai’s aunt.

As they rounded the corner to the next stairwell, Lilia heard shouting.

A ragged figure loped up the stairs on all fours. Lilia thought it was an animal. She saw filthy skin, a tangle of long hair, a shredded hide of some kind that she only realized was a torn garment when the figure barreled into her. The thing thumped its head into her stomach, knocking Lilia back.

The creature snarled at her, tearing at her face and clothes. Lilia lashed out with her good hand. Hit it in the face. It squealed. The face was young, the mouth twisted. Where its eyes should have been were two pools of scarred flesh.

“What is it?” Gian shrieked. She cowered a few feet away, hands raised.

Lilia called Oma, pulling a long thread of breath and knotting it into a burst of fire. The breathy red mist pushed the thing off her. It tangled with the spell, growling and snarling as it tumbled down the steps.

Ghrasia Madah, leader of the militia in Liona, rushed up the steps just as the thing began to tumble. She caught it by the shoulders, shouting, “Off now!” as if the feral thing was a dog or a bear.

Lilia pressed her hand to her cheek where it had scratched her. The thing began to whine and tremble at Ghrasia’s feet, and it was only then that Lilia realized it was a real human being, not some beast.

Gian hurried to Lilia’s side and helped her up.

“I’m sorry,” Ghrasia said. She held the little feral girl close. “She hasn’t attacked anyone here before.” Ghrasia straightened. The girl crouched beside her, head hanging low, hair falling into her face. She nuzzled Ghrasia’s hand like a dog. “She was treated badly,” Ghrasia said. “She’s my responsibility.”

Lilia smoothed her dress. She was still wearing the white muslin dress and white hair ribbons she had put on to give her the appearance of the Dhai martyr Faith Ahya. In the shadow of the rising suns, her skin glowing through a gifted trick, and flying to the top of the wall with the aid of several air-calling parajistas bound to her cause, the ruse had worked to sway the Dhai of Liona to open the gate. But in the stark light of day, Lilia suspected she looked filthy, broken, and ridiculous.

“Why are you responsible?” Lilia said. “Surely you aren’t her mother. She doesn’t have a clan, does she? She is not Dhai at all.”

“Many would say the same of you,” Ghrasia said. “When I took up a sword, I accepted that there were some bad things I’d have to do. I wanted to temper them with good. It was up to me, now, to decide who was the monster, who the victim. That’s harder than you might think, and it’s a terrible power. One must use that power for something better, sometimes.” The feral girl nuzzled her hand.

Lilia could not bite back her retort. “That girl attacked me. It’s not as if I left thousands of people to die, crushed up against that wall, the way you did during the Pass War.”

Ghrasia said nothing, but her expression was stony. Lilia regretted what she’d said immediately. But before she could recant, Ghrasia called the girl back, and they walked down the long curving tongue of the stairs.

“Let’s find another stairway,” Gian said. “I want to find Taigan before she makes a mess. Her jokes don’t go over well here.”

But Lilia stayed rooted there, looking after Ghrasia. “She thinks she’s better,” Lilia said, “because she guards some monster. I’m protecting hundreds of people. Innocent, peaceful people.”

Lilia imagined all of Dhai burning, just the way the Tai Mora wanted. She needed to speak to Taigan more urgently than ever, because choosing sides was becoming more difficult.

“Let them make their own mistakes,” Gian said, pulling at her hand again. “They aren’t your people any more than they’re mine.”

But Lilia had lost track of who her people were supposed to be a long time ago.

They found Taigan tussling with a young man on the paving stones outside the dog and bear kennels. Lilia thought for a moment that Taigan had indeed started telling her morbid jokes, and gravely offended him.

“Tira’s tears,” Lilia said. “Who is this?”

Taigan gripped the man by the back of his tunic and flung him at Lilia’s feet. “Ask this man where he’s been,” Taigan said.

The man wasn’t much older than Lilia – maybe eighteen or nineteen. His face was smeared in mud and bear dung. She saw blood at the corner of his mouth.

For a moment, the sight of the blood repulsed her. Then she squared her shoulders and said, with a voice surer than she felt, “You should have known better than to provoke a Saiduan.”

“You’ll both be exiled for this abuse,” he said. “Violence against me. Touching without consent. These are crimes!”

“I caught him in your room,” Taigan said, gesturing behind her to the storage room off the kennels that they had been housed in by the militia.

“They say you’re Faith Ahya reborn,” the man said. “My grandmother is ill, and with Tira in decline, there’s no tirajista powerful enough to save her. But they say Faith Ahya could heal people, even when Tira was in decline. Can you?”

“He’s lying. He’s a spy,” Taigan said.

“Where is your grandmother?” Lilia asked. His plea reminded her of her own mother. She would have given anything to save her mother, but she had not been powerful enough, or clever enough.

“Clan Osono,” he said.

“Perhaps I will see her,” Lilia said, “when things have settled here. I have a responsibility to the Dhai as much as the dajians I’ve brought here.”

Taigan said something harsh in Saiduan, and whirled back toward their shared room.

“Forgive Taigan,” she said. “She has a very strange sense of things. It may be a few days before I can see your grandmother. There is much to sort out here, and the Kai may still condemn me to exile.”

“It won’t happen,” the man said. “We won’t let it.” He scrambled to his feet and ran off, clutching at his side. Lilia wondered if Taigan had broken his ribs. Violence would call even more attention to them than bad jokes.

“Can you help him, really?” Gian asked.

“Maybe,” Lilia said. She knew that helping the Dhai in the valley would go a long way toward the acceptance of the refugees. If she had turned him away, he would have brought back stories to his clan about some arrogant little no-nothing girl and her stinking refugees. She needed to create another story, or the refugees would find no welcome in Dhai.

Gian stroked her arm. Lilia pulled away, annoyed. She had gotten used to touching without consent in the camps – it wasn’t considered rude in Dorinah – but that didn’t make it easier to tolerate. In that moment she found it deeply offensive. Something about seeing Taigan’s brute rage at the young man had shaken her. It reminded her of who she could be.

Gian said she would get them food, though Lilia knew they needed none. Gian had become obsessed with food since they arrived in Liona, and had started secreting bits of it away in their sleeping quarters. Lilia once found an apple under her pillow.

Lilia walked back into the musty storage room they had called home for nearly a week. Taigan sat on a large barrel, muttering to herself in Saiduan. She ran a stone across her blade.

Lilia sat on the straw mattress on the floor. She saw a brown wrapper peeking out from under the mattress and pulled it out. It was a hunk of rye bread wrapped in brown paper.

Taigan grunted at it. “She’s going to start drawing vermin.”

Lilia tapped at the flame fly lantern, rousing the flies to give them some light. “You sit in the dark too much,” she said.

“This Gian girl is like your dog,” Taigan said. “Dogs hoard food and lick their masters’ feet. You trust a dog?”

“That’s unfair.”

“You know nothing of her.”

“I know less of you. But I put up with you too.” In truth, her feelings about Gian were confused. Did she like this Gian for who she was, or because she reminded her so strongly of the woman who died for her? She tucked the bread back under the mattress. She didn’t want to know what else was under there.

“Which is just as curious,” Taigan said. She balanced her blade on her thigh. Her mouth thinned. Lilia saw her arm flex. Then move.

Taigan’s blade flashed at Lilia’s face.

Lilia reflexively snatched at Oma. She caught the end of Taigan’s blade in red tangles of breath.

Taigan blew a puff of misty breath over Lilia’s tangles, disintegrating them. “Still so much to learn,” Taigan said. She began to sharpen the blade again.

Lilia pillowed her hands beneath her head. Taigan’s little tricks were growing tedious. Some days Lilia wanted to bundle Taigan up with some clever spell while she slept and leave her there. But most of what she knew of Oma now was self taught. There were hundreds, if not thousands, of songs and litanies to learn, and all she knew were those Taigan had taught her in the mountains and here during their long wait together.

“I don’t have a lot of friends,” Lilia said. “Don’t try and make Gian mean.”

“It’s a sorry day,” Taigan said, “when a young girl’s friends are an outcast sanisi and some politicking snake.”

Taigan jabbed the sword at the wall now, feinting at some unseen enemy. Lilia wondered what enemies she fought when she slept. Taigan cried out in Saiduan at night, wrestling with terrible dreams that made her curse and howl. Lilia had taken to sleeping with a pillow over her head.

“Not everyone is like you,” Lilia said, “some spy or assassin trying to use other people.”

“You and I disagree on many things, bird,” Taigan said. She sheathed her blade and stood to look out the tiny window at the back of the storage room. Motes of dust clotted the air. “But we must agree on what comes next. You cannot stay here mending people’s mad mothers.” A blooming red mist surrounded her.

Lilia countered with the Song of the Proud Wall, a defensive block, mouthing the words while calling another huff of breath to build a snarling counterattack.

Taigan’s spell crashed into her barrier. The meshes of breath wrangled for dominance.

Taigan deployed another offense. Always offensive, with Taigan. Lilia knotted up another defensive spell and let go.

“These are my people,” Lilia said. “We won’t let that other Kai win.”

“This country doesn’t know what to do with you,” Taigan said, and Lilia recognized the Song of the Cactus right before she spoke, and muttered her own counterattack. She released it before Taigan got out her next sentence. Ever since she had learned to draw on Oma, using the songs Taigan had taught her was easy. “I can take you away from here under the cover of dark. The Saiduan would welcome you. We know what you are, and how to…”

“How to use me?”

Lilia leaned forward, concentrating on the Song of the Mountain, trying to call it up and twist the strands she needed without mouthing the words and giving her move away while Taigan’s Song of the Cactus and her Song of the Water Spider warred in great clouds of seething, murderous power.

“So indelicate.” Taigan said. Six tendrils from the Song of the Cactus kicked free of the Water Spider defense and grabbed Lilia’s throat. She huffed out another defense. She was sweating now.

Taigan neatly deployed another offense, a roiling tide of red that spilled over their tangling spells and wafted over Lilia’s protective red bubble. Lilia had four active spells now. If she panicked, if she lost her focus, Taigan would overwhelm her. She did not like losing.

“And what will they do here without us?” she wheezed, calling another huff of Oma’s power beneath her skin for a fifth offensive spell. Taigan had no defenses. All Lilia had to do was switch tactics long enough to overwhelm her.

Taigan shrugged. But Lilia saw the movement of her lips, and the spell she was trying to hide with that shrug. Defensive barrier. It was coming.

Lilia released her offensive spell, six brilliant woven balls of Oma’s breath, hurtling at Taigan like moths to claw lilies.

“If I leave,” Lilia said, untangling the spell at her throat. “The Kai will throw my people back into Dorinah, and everyone left will be killed by the Tai Mora.”

Her red mist collided with an offensive spell, something Lilia hadn’t anticipated. But one of hers got through, curling back behind Taigan’s left shoulder, half of it slipping through before Taigan’s defensive Song of the Pearled Wall went up.

Taigan hissed, flicked her hand, and mitigated the worst of the damage. But Lilia felt a burst of satisfaction on seeing the shoulder of Taigan’s tunic smoking.

“I am a sanisi, not a seer,” Taigan said. “I cannot see all futures.” Taigan clapped her hands, and deployed some song Lilia didn’t know, neatly cutting Lilia off from calling on Oma.

Lilia’s warring spells dissipated, as did Taigan’s. The air smelled faintly of copper. Lilia sneezed.

“It’s unfair to use a trick you won’t teach me,” Lilia said.

“I’d be a fool to do that,” Taigan said. “The Song of Unmaking is all a teacher has to control a student. If I let you keep pulling, you’d burn yourself out.”

“I wouldn’t.”

“You would. You seek to win at all costs, even when the odds are against you. But drawing on Oma isn’t some strategy game.”

“That’s exactly what it is.”

“The stakes are higher.”

Gian pushed in with a tray of food – lemon and cilantro rice, steamed vegetables, a decadent platter of fruit spanning a surprisingly wide range of colors, considering the season. She pressed the tray at Lilia.

Seeing so much food made Lilia nauseous. “Where did you get this?”

“I said it was for you. More people here like you than you think.” Gian set the tray on the floor. She pulled two sticky rice balls from her pockets and crawled to the edge of the mattress. Lilia watched her a moment, wondering where she would think to put them, but Gian simply held them, contentedly, in her lap.

“What do you think about helping the Dhai fight?” Lilia asked.

“I don’t know,” Gian said. “What does it mean to be a god, Faith Ahya reborn?”

“Bearing babies,” Taigan said.

“Oh, be quiet,” Lilia said. “If there’s a war, I will win it. I’m not afraid anymore.”

“Heroes are honest cowards,” Taigan said, “who fight though they fear it. Only fools feel no fear.”

“I was afraid my whole life, and it got me nothing.”

Taigan muttered something in Saiduan. Then, “Fear tempers bad choices, bird.”

“I’ve made my decision,” Lilia said. “You can help me convince the Kai to let the refugees stay, and to help me get them accepted here so we can fight the Tai Mora, or you can go. Both of you.”

Gian said, “If you aren’t going to eat–”

“Take it,” Lilia said.

Gian picked up the tray. Taigan stood, muttering. “Bird, this choice changes everything. The whole landscape of your life. If you come to Saiduan…”

“I made my choice,” Lilia said.

She heard footsteps outside, and turned just as two of the militia stepped up to the door.

Taigan moved to block them as the smallest one drew herself up and said, “The Kai is on his way to pass judgment, and Ghrasia Madah wishes to see you immediately.”

Excerpted from Empire Ascendant © Kameron Hurley, 2015