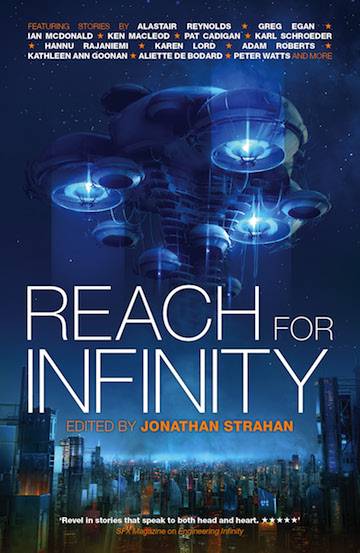

Tor.com is pleased to present Ian McDonald’s “The Fifth Dragon” to celebrate the forthcoming September publication of Luna: New Moon. “The Fifth Dragon” was originally published in Reach For Infinity, a 2014 anthology from Solaris Books, edited by Jonathan Strahan, of stories about humanity taking its first steps off of Earth.

From Niall Alexander’s review of Reach For Infinity: “The Fifth Dragon” is about a pair of new moon workers, Achi and Adriana, who find comfort in this alien place in one another’s company, only to learn that their time together is strictly limited. ‘The Fifth Dragon’ flies back and forth between their first days as a pair and their final moments as friends, underscoring that the end of everything is inevitable.

The scan was routine. Every moon worker has one every four lunes. Achi was called, she went into the scanner. The machine passed magnetic fields through her body and when she came out the medic said, you have four weeks left.

We met on the Vorontsov Trans-Orbital cycler but didn’t have sex. We talked instead about names.

“Corta. That’s not a Brazilian name,” Achi said. I didn’t know her well enough then, eight hours out from transfer orbit, to be my truculent self and insist that any name can be a Brazilian name, that we are a true rainbow nation. So I told her that my name had rolled through many peoples and languages like a bottle in a breaker until it was cast up sand-scoured and clouded on the beaches of Barra. And now I was taking it on again, up to the moon.

Achi Debasso. Another name rolled by tide of history. London born, London raised, M.I.T. educated but she never forgot – had never been let forget – that she was Syrian. Syriac. That one letter was a universe of difference. Her family had fled the civil war, she had been born in exile. Now she was headed into a deeper exile.

I didn’t mean to be in the centrifuge pod with Achi. There was a guy; he’d looked and I looked back and nodded yes, I will, yes even as the OTV made its distancing burn from the cycler. I took it. I’m no prude. I’ve got the New Year Barra beach bangles. I’m up for a party and more, and everyone’s heard about (here they move in close and mouth the words) freefall sex. I wanted to try it with this guy. And I couldn’t stop throwing up. I was not up for zero gee. It turned everything inside me upside down. Puke poured out of me. That’s not sexy. So I retreated to gravity and the only other person in the centrifuge arm was this caramel-eyed girl, slender hands and long fingers, her face flickering every few moments into an unconscious micro-frown. Inward-gazing, self-loathing, scattering geek references like anti-personnel mines. Up in the hub our co-workers fucked. Down in the centrifuge pod we talked and the stars and the moon arced across the window beneath our feet.

A Brazilian miner and a London-Syriac ecologist. The centrifuge filled as freefall sex palled but we kept talking. The next day the guy I had puked over caught my eye again but I sought out Achi, on her own in the same spot, looking out at the moon. And the whirling moon was a little bigger in the observation port and we knew each other a little better and by the end of the week the moon filled the whole of the window and we had moved from conversationalists into friends.

Achi: left Damascus as a cluster of cells tumbling in her mother’s womb. And that informed her every breath and touch. She felt guilty for escaping. Father was a software engineer, mother was a physiotherapist. London welcomed them.

Adriana: seven of us: seven Cortas. Little cuts. I was in the middle, loved and adored but told solemnly I was plain and thick in the thighs and would have be thankful for whatever life granted me.

Achi: a water girl. Her family home was near the Olympic pool – her mother had dropped her into water days out of the hospital. She had sunk, then she swam. Swimmer and surfer: long British summer evenings on the western beaches. Cold British water. She was small and quiet but feared no wave.

Adriana: born with the sound of the sea in her room but never learned to swim. I splash, I paddle, I wade. I come from beach people, not ocean people.

Achi: the atoner. She could not change the place or order of her birth, but she could apologise for it by being useful. Useful Achi. Make things right!

Adriana: the plain. Mãe and papai thought they were doing me a favour; allowing me no illusions or false hopes that could blight my life. Marry as well as you can; be happy: that will have to do. Not this Corta. I was the kid who shot her hand up at school. The girl who wouldn’t shut up when the boys were talking. Who never got picked for the futsal team – okay, I would find my own sport. I did Brasilian jujitsu. Sport for one. No one messed with plain Adriana.

Achi: grad at UCL, post-grad at M.I.T. Her need to be useful took her battling desertification, salinisation, eutrophication. She was an -ation warrior. In the end it took her to the moon. No way to be more useful than sheltering and feeding a whole world.

Adriana: university at São Paulo. And my salvation. Where I learned that plain didn’t matter as much as available, and I was sweet for sex with boys and girls. Fuckfriends. Sweet girls don’t have fuckfriends. And sweet girls don’t study mining engineering. Like jujitsu, like hooking up, that was a thing for me, me alone. Then the economy gave one final, apocalyptic crash at the bottom of a series of drops and hit the ground and broke so badly no one could see how to fix it. And the seaside, be-happy Cortas were in ruins, jobless, investments in ashes. It was plain Adriana who said, I can save you. I’ll go to the Moon.

All this we knew by the seventh day of the orbit out. On the eight day, we rendezvoused with the transfer tether and spun down to the new world.

The freefall sex? Grossly oversold. Everything moves in all the wrong ways. Things get away from you. You have to strap everything down to get purchase. It’s more like mutual bondage.

I was sintering ten kilometres ahead of Crucible when Achi’s call came. I had requested the transfer from Mackenzie Metals to Vorontsov Rail. The forewoman had been puzzled when I reported to Railhead. You’re a dustbunny not a track-queen. Surface work is surface work, I said and that convinced her. The work was good, easy and physical and satisfying. And it was on the surface. At the end of every up-shift you saw six new lengths of gleaming rail among the boot and track prints, and on the edge of the horizon, the blinding spark of Crucible, brighter than any star, advancing over yesterday’s rails, and you said, I made that. The work had real measure: the inexorable advance of Mackenzie Metals across the Mare Insularum, brighter than the brightest star. Brighter than sunrise, so bright it could burn a hole through your helmet sunscreen if you held it in your eye line too long. Thousands of concave mirrors focusing sunlight on the smelting crucibles. Three years from now the rail lines would circle the globe and the Crucible would follow the sun, bathed in perpetual noon. Me, building a railroad around the moon.

Then ting ching and it all came apart. Achi’s voice blocking out my work-mix music, Achi’s face superimposed on the dirty grey hills of Rimae Maestlin. Achi telling me her routine medical had given her four weeks.

I hitched a ride on the construction car back down the rails to Crucible. I waited two hours hunkered down in the hard-vacuum shadows, tons of molten metal and ten thousand Kelvin sunlight above my head, for an expensive ticket on a slow Mackenzie ore train to Meridian. Ten hours clinging onto a maintenance platform, not even room to turn around, let alone sit. Grey dust, black sky… I listened my way through my collection of historical bossanova, from the 1940 to the 1970s. I played Connecto on my helmet hud until every time I blinked I saw tumbling, spinning gold stars. I scanned my family’s social space entries and threw my thoughts and comments and good wishes at the big blue Earth. By the time I got to Meridian I was two degrees off hypothermic. My surface activity suit was rated for a shift and some scramble time, not twelve hours in the open. Should have claimed compensation. But I didn’t want my former employers paying too much attention to me. I couldn’t afford the time it would take to re-pressurise for the train, so I went dirty and fast, on the BALTRAN.

I knew I would vomit. I held it until the third and final jump. BALTRAN: Ballistic Transport system. The moon has no atmosphere – well, it does, a very thin one, which is getting thicker as human settlements leak air into it. Maybe in a few centuries this will become a problem for vacuum industries, but to all intents and purposes, it’s a vacuum. See what I did there? That’s the engineer in me. No atmosphere means ballistic trajectories can be calculated with great precision. Which means, throw something up and you know exactly where it will fall to moon again. Bring in positionable electromagnetic launchers and you have a mechanism for schlepping material quick and dirty around the moon. Launch it, catch it in a receiver, boost it on again. It’s like juggling. The BALTRAN is not always used for cargo. If you can take the gees it can as easily juggle people across the moon.

I held it until the final jump. You cannot imagine what it is like to throw up in your helmet. In free fall. People have died. The look on the BALTRAN attendant’s face when I came out of the capsule at Queen of the South was a thing to be seen. So I am told. I couldn’t see it. But if I could afford the capsule I could afford the shower to clean up. And there are people in Queen who will happily clean vomit out of a sasuit for the right number of bitsies. Say what you like about the Vorontsovs, they pay handsomely.

All this I did, the endless hours riding the train like a moon-hobo, the hypothermia and being sling-shotted in a can of my own barf, because I knew that if Achi had four weeks, I could not be far behind.

You don’t think about the bones. As a Jo Moonbeam, everything is so new and demanding, from working out how to stand and walk, to those four little digits in the bottom right corner of your field of vision that tell you how much you owe the Lunar Development Corporation for air, water, space and web. The first time you see those numbers change because demand or supply or market price has shifted, your breath catches in your throat. Nothing tells you that you are not on Earth any more than exhaling at one price and inhaling at another. Everything – everything – was new and hard.

Everything other than your bones. After two years on the moon human bone structure atrophies to a point where return to Earth gravity is almost certainly fatal. The medics drop it almost incidentally into your initial assessment. It can take days – weeks – for its ripples to touch your life. Then you feel your bones crumbling away, flake by flake, inside your body. And there’s not a thing you can do about it. What it means is that there is a calcium clock ticking inside your body, counting down to Moon Day. The day you decide: do I stay or do I go?

In those early days we were scared all the time, Achi and I. I looked after her – I don’t know how we fell into those roles, protector and defended, but I protected and she nurtured and we won respect. There were three moon men for every moon woman. It was a man’s world; a macho social meld of soldiers camped in enemy terrain and deep-diving submariners. The Jo Moonbeam barracks were exactly that; a grey, dusty warehouse of temporary accommodation cabins barely the safe legal minimum beneath the surface. We learned quickly the vertical hierarchy of moon society: the lower you live – the further from surface radiation and secondary cosmic rays – the higher your status. The air was chilly and stank of sewage, electricity, dust and unwashed bodies. The air still smells like that; I just got used to the funk in my lungs. Within hours the induction barracks self-sorted. The women gravitated together and affiliated with the astronomers on placement with the Farside observatory. Achi and I traded to get cabins beside each other. We visited, we decorated, we entertained, we opened our doors in solidarity and hospitality. We listened to the loud voices of the men, the real men, the worldbreakers, booming down the aisles of cabins, the over-loud laughter. We made cocktails from cheap industrial vodka.

Sexual violence, games of power were in the air we breathed, the water we drank, the narrow corridors through which we squeezed, pressing up against each other. The moon has never had criminal law, only contract law, and when Achi and I arrived the LDC was only beginning to set up the Court of Clavius to settle and enforce contracts. Queen of the South was a wild town. Fatalities among Jo Moonbeams ran at ten percent. In our first week, an extraction worker from Xinjiang was crushed in a pressure lock. The Moon knows a thousand ways to kill you. And I knew a thousand and one.

Cortas cut. That was our family legend. Hard sharp fast. I made the women’s Brazilian jujitsu team at university. It’s hard, sharp, fast: the perfect Corta fighting art. A couple of basic moves, together with lunar gravity, allowed me to put over the most intimidating of sex pests. But when Achi’s stalker wouldn’t take no, I reached for slower, subtler weapons. Stalkers don’t go away. That’s what makes them stalkers. I found which Surface Activity training squad he was on and made some adjustments to his suit thermostat. He didn’t die. He wasn’t meant to die. Death would have been easier than my revenge for Achi. He never suspected me; he never suspected anyone. I made it look like a perfect malfunction. I’m a good engineer. I count his frostbite thumb and three toes as my trophies. By the time he got out of the med centre, Achi and I were on our separate ways to our contracts.

That was another clock, ticking louder than the clock in our bones. I&A was four weeks. After that, we would go to work. Achi’s work in ecological habitats would take her to the underground agraria the Asamoah family were digging under Amundsen. My contract was with Mackenzie Metals; working out on the open seas. Working with dust. Dustbunny. We clung to the I&A barracks, we clung to our cabins, our friends. We clung to each other. We were scared. Truth: we were scared all the time, with every breath. Everyone on the moon is scared, all the time.

There was a party; moon mojitos. Vodka and mint are easy up here. But before the music and the drinking: a special gift for Achi. Her work with Aka would keep her underground; digging and scooping and sowing. She need never go on the surface. She could go her whole career – her whole life – in the caverns and lava tubes and agraria. She need never see the raw sky.

The suit hire was cosmologically expensive, even after negotiation. It was a GP surface activity shell; an armoured hulk to my lithe sasuit spiderwoman. Her face was nervous behind the faceplate; her breathing shallow. We held hands in the outlock as the pressure door slid up. Then her faceplate polarised in the sun and I could not see her any more. We walked up the ramp amongst a hundred thousand boot prints. We walked up the ramp and few metres out on to the surface, still holding hands. There, beyond the coms towers and the power relays and the charging points for the buses and rovers; beyond the grey line of the crater rim that curved on the close horizon and the shadows the sun had never touched; there perched above the edge of our tiny world we saw the full earth. Full and blue and white, mottled with greens and ochres. Full and impossible and beautiful beyond any words of mine. It was winter and the southern hemisphere was offered to us; the ocean half of the planet. I saw great Africa. I saw dear Brazil.

Then the air contract advisory warned me that we were nearing the expiry of our oxygen contract and we turned out backs on the blue earth and walked back down into the moon.

That night we drank to our jobs, our friends, our loves and our bones. In the morning we parted.

We met in a café on the twelfth level of the new Chandra Quadra. We hugged, we kissed, we cried a little. I smelled sweet by then. Below us excavators dug and sculpted, a new level every ten days. We held each other at arms’ length and looked at each other. Then we drank mint tea on the balcony.

I loathe mint tea.

Mint tea is a fistful of herbs jammed in a glass. Sloshed with boiling water. Served scalded yet still flavourless. Effete like herbal thés and tisanes. Held between thumb and forefinger: so. Mint leaves are coarse and hairy. Mint tea is medicinal. Add sugar and it becomes infantile. It is drinking for the sake of doing something with your fingers.

Coffee is a drink for grownups. No kid ever likes coffee. It’s psychoactive. Coffee is the drug of memory. I can remember the great cups of coffee of my life; the places, the faces, the words spoken. It never quite tastes the way it smells. If it did, we would – drink it until out heads exploded with memory,

But coffee is not an efficient crop in our ecology. And imported coffee is more expensive than gold. Gold is easy. Gold I can sift from lunar regolith. Gold is so easy its only value is decorative. It isn’t even worth the cost of shipment to Earth. Mint is rampant. Under lunar gravity, it forms plants up to three metres tall. So we are a nation of mint tea drinkers.

We didn’t talk about the bones at once. It was eight lunes since we last saw each other: we talk on the network daily, we share our lives but it takes face to face contact to ground all that; make it real.

I made Achi laugh. She laughed like soft rain. I told her about King Dong and she clapped her hands to her mouth in naughty glee but laughed with her eyes. King Dong started as a joke but shift by shift was becoming reality. Footprints last forever on the moon, a bored surface worker had said on a slow shift rotation back to Crucible. What if we stamped out a giant spunking cock, a hundred kilometres long? With hairy balls. Visible from Earth. It’s just a matter of co-ordination. Take a hundred male surface workers and an Australian extraction company and joke becomes temptation becomes reality. So wrong. So funny.

And Achi?

She was out of contract. The closer you are to your Moon Day, the shorter the contract, sometimes down to minutes of employment, but this was different. Aka did not want her ideas any more. They were recruiting direct from Accra and Kumasi. Ghanaians for a Ghanaian company. She was pitching ideas to the Lunar Development Corporation for their new port and capital at Meridian – quadras three kilometres deep; a sculpted city; like living in the walls of a titanic cathedral. The LDC was polite but it had been talking about development funding for two lunes now. Her savings were running low. She woke up looking at the tick of the Four Fundamentals on her lens. Oxygen water space coms: which do you cut down on first? She was considering moving to a smaller space.

“I can pay your per diems,” I said. “I have lots of money.”

And then the bones… Achi could not decide until I got my report. I never knew anyone suffered from guilt as acutely as her. She could not have borne it if her decision had influenced my decision to stay with the moon or go back to Earth,

“I’ll go now,” I said. I didn’t want to. I didn’t want to be here on this balcony drinking piss-tea. I didn’t want Achi to have forced a decision on me. I didn’t want there to be a decision for me to make. “I’ll get the tea.”

Then the wonder. In the corner of my vision, a flash of gold. A lens malfunction – no, something marvellous. A woman flying. A flying woman. Her arms were outspread, she hung in the sky it like a crucifix. Our Lady of Flight. Then I saw wings shimmer and run with rainbow colours; wings transparent and strong as a dragonfly’s. The woman hung a moment, then folded her gossamer wings around her, and fell. She tumbled, now diving heard-first, flicked her wrists, flexed her shoulders. A glimmer of wing slowed her; then she spread her full wing span and pulled up out of her dive into a soaring spiral, high into the artificial sky of Chandra Quadra.

“Oh,” I said. I had been holding my breath. I was shaking with wonder. I was chewed by jealousy.

“We always could fly” Achi said. “We just haven’t had the space. Until now.”

Did I hear irritation in Achi’s voice, that I was so bewitched by the flying woman? But if you could fly why would you ever do anything else?

I went to the Mackenzie Metals medical centre and the medic put me in the scanner. He passed magnetic fields through my body and the machine gave me my bone density analysis. I was eight days behind Achi. Five weeks, and then my residency on the moon would become citizenship.

Or I could fly back to Earth, to Brazil.

There are friends and there are friends you have sex with.

After I&A it was six lunes until I saw Achi again. Six lunes in the Sea of Fertility, sifting dust. The Mackenzie Metals Messier unit was old, cramped, creaking: cut-and-cover pods under bulldozed regolith berms. Too frequently I was evacuated to the new, lower levels by the radiation alarm. Cosmic rays kicked nasty secondary particles out of moon dust, energetic enough to penetrate the upper levels of the unit. Every time I saw the alarm flash its yellow trefoil in my lens I felt my ovaries tighten. Day and night the tunnels trembled to the vibration of the digging machines, deep beneath even those evacuation tunnels, eating rock. There were two hundred dustbunnies in Messier. After a month’s gentle and wary persistence and charm from a 3D print designer, I joined the end of a small amory: my Chu-yu, his homamor in Queen, his hetamor in Meridian, her hetamor also in Meridian. What had taken him so long, Chu-yu confessed, was my rep. Word about the sex pest on I&A with the unexplained suit malfunction. I wouldn’t do that to a co-worker, I said. Not unless severely provoked. Then I kissed him. The amory was warmth and sex, but it wasn’t Achi. Lovers are not friends

Sun Chu-yu understood that when I kissed him goodbye at Messier’s bus lock. Achi and I chatted on the network all the way to the railhead at Hypatia, then all the way down the line to the South. Even then, only moments since I had last spoken to her image on my eyeball, it was a physical shock to see her at the meeting point in Queen of the South station: her, physical her. Shorter than I remembered. Absence makes the heart grow taller.

Such fun she had planned for me! I wanted to dump my stuff at her place but no; she whirled me off into excitement. After the reek and claustrophobia of Messier Queen of the South was intense, loud, colourful, too too fast. In only six lunes it had changed beyond recognition. Every street was longer, every tunnel wider, every chamber loftier. When she took me in a glass elevator down the side of the recently completed Thoth Quadra I reeled from vertigo. Down on the floor of the massive cavern was a small copse of dwarf trees – full-size trees would reach the ceiling, Achi explained. There was a café. In that café I first tasted and immediately hated mint tea.

I built this, Achi said. These are my trees, this is my garden.

I was too busy looking up at the lights, all the lights, going up and up.

Such fun! Tea, then shops. I had had to find a party dress. We were going to a special party, that night. Exclusive. We browsed the catalogues in five different print shops before I found something I could wear: very retro, 1950s inspired, full and layered, it hid what I wanted hidden. Then, the shoes.

The special party was exclusive to Achi’s workgroup and their F&Fs’. A security-locked rail capsule took us through a dark tunnel into a space so huge, so blinding with mirrored light, that once again I reeled on my feet and almost threw up over my Balenciaga. An agrarium, Achi’s last project. I was at the bottom of a shaft a kilometretall, fifty metres wide. The horizon is close at eye level on the moon; everything curves. Underground, a different geometry applies. The agrarium was the straightest thing I had seen in months. And brilliant: a central core of mirrors ran the full height of the shaft, bouncing raw sunlight one to another to another towalls terraced with hydroponic racks. The base of the shaft was a mosaic of fish tanks, criss-crossed by walkways. The air was warm and dank and rank. I was woozy with CO2. In these conditions plants grew fast and tall; potato plants the size of bushes; tomato vines so tall I lost their heads in the tangle of leaves and fruit. Hyper-intensive agriculture: the agrarium was huge for a cave, small for an ecosystem. The tanks splashed with fish. Did I hear frogs? Were those ducks?

Achi’s team had built a new pond from waterproof sheeting and construction frame. A pool. A swimming pool. A sound system played G-pop. There were cocktails. Blue was the fashion. They matched my dress. Achi’s crew were friendly and expansive. They never failed to compliment me on my fashion. I shucked it and my shoes and everything else for the pool. I lolled, I luxuriated, I let the strange, chaotic eddies waft green, woozy air over me while over my head the mirrors moved. Achi swam up beside me and we trod water together, laughing and plashing. The agrarium crew had lowered a number of benches into the pool to make a shallow end. Achi and I wafted blood-warm water with our legs and drank Blue Moons.

I am always up for a party.

I woke up in bed beside her the next morning; shit-headed with moon vodka. I remembered mumbling, fumbling love. Shivering and stupid-whispering, skin to skin. Fingerworks. Achi lay curled on her right side, facing me. She had kicked the sheet off in the night. A tiny string of drool ran from the corner of her mouth to the pillow and trembled in time to her breathing.

I looked at her there, her breath rattling in the back of her throat in drunk sleep. We had made love. I had sex with my dearest friend. I had done a good thing, I had done a bad thing. I had done an irrevocable thing. Then I lay down and pressed myself in close to her and she mumble-grumbled and moved in close to me and her fingers found me and we began again.

I woke in the dark with the golden woman swooping through my head. Achi slept beside me. The same side, the same curl of the spine, the same light rattle-snore and open mouth as that first night. When I saw Achi’s new cabin, I booked us into a hostel. The bed was wide, the air was as fresh as Queen of the South could make and the taste of the water did not set your teeth on edge.

Golden woman, flying loops through my certainties.

Queen of the South never went fully dark – lunar society is 24-hour society. I pulled Achi’s unneeded sheet around me and went out on to the balcony. I leaned on the rail and looked out at the walls of lights. Apts, cabins, walkways and staircases. Lives and decisions behind every light. This was an ugly world. Hard and mean. It put a price on everything. It demanded a negotiation from everyone. Out at Railhead I had seen a new thing among some of the surface workers: a medallion, or a little votive tucked into a patch pocket. A woman in Virgin Mary robes, one half of her face a black angel, the other half a naked skull. Dona Luna: goddess of dust and radiation. Our Lady Liberty, our Britannia, our Marianne, our Mother Russia. One half of her face dead, but the other alive. The moon was not a dead satellite, it was a living world. Hands and hearts and hopes like mine shaped it. There was no mother nature, no Gaia to set against human will. Everything that lived, we made. Dona Luna was hard and unforgiving, but she was beautiful. She could be a woman, with dragonfly wings, flying.

I stayed on the hotel balcony until the roof reddened with sun-up. Then I went back to Achi. I wanted to make love with her again. My motives were all selfish. Things that are difficult with friends are easier with lovers.

My grandmother used to say that love was the easiest thing in the world. Love is what you see every day.

I did not see Achi for several lunes after the party in Queen. Mackenzie Metals sent me out into the field, prospecting new terrain in the Sea of Vapours. Away from Messier, it was plain to me and Sun Chu-yu that the amory didn’t work. You love what you see every day. All the amors were happy for me to leave. No blame, no claim. A simple automated contract, terminated.

I took a couple of weeks furlough back in Queen. I had called Achi about hooking up but she was at a new dig at Twe, where the Asamoahs were building a corporate headquarters. I was relieved. And then was guilty that I had felt relieved. Sex had made everything different. I drank, I partied, I had one night stands, I talked long hours of expensive bandwidth my loved ones back on Earth. They thanked me for the money, especially the tiny kids. They said I looked different. Longer. Drawn out. My bones eroding, I said. There they were, happy and safe. The money I sent them bought their education. Health, weddings, babies. And here I was, on the moon. Plain Adriana, who would never get a man, but who got the education, who got the degree, who got the job, sending them the money from the moon.

They were right. I was different. I never felt the same about that blue pearl of Earth in the sky. I never again hired a sasuit to go look at it, just look at it. Out on the surface, I disregarded it.

The Mackenzies sent me out next to the Lansberg extraction zone and I saw the thing that made everything different.

Five extractors were working Lansberg. They were ugly towers of Archimedes screws and grids and transport belts and wheels three times my height, all topped out by a spread of solar panels that made them look like robot trees. Slow-moving, cumbersome, inelegant. Lunar design tends to the utilitarian, the practical. The bones on show. But to me they were beautiful. Marvellous trees. I saw them one day, out on the regolith, and I almost fell flat from the revelation. Not what they made – separating rare earth metals from lunar regolith – but what they threw away. Launched in high, arching ballistic jets on either side of the big, slow machines.

It was the thing I saw every day. One day you look at the boy on the bus and he sets your heart alight. One day you look at the jets of industrial waste and you see riches beyond measure.

I had to dissociate myself from anything that might link me to regolith waste and beautiful rainbows of dust.

I quit Mackenzie and became a Vorontsov track queen.

I want to make a game of it, Achi said. That’s the only way I can bear it. We must clench our fists behind our backs, like Scissors Paper Stone, and we must count to three, and then we open our fists and in them there will be something, some small object, that will say beyond any doubt what we have decided. We must not speak, because if we say even a word, we will influence each other. That’s the only way I can bear it if it is quick and clean and we don’t speak. And a game.

We went back to the balcony table of the café to play the game. It was now on the 13th level. Two glasses of mint tea. No one was flying the great empty spaces of Chandra Quadra this day. The air smelled of rock dust over the usual electricity and sewage. Every fifth sky panel was blinking. An imperfect world.

Attempted small talk. Do you want some breakfast? No, but you have some. No I’m not hungry. I haven’t seen that top before. The colour is really good for you. Oh it’s just something I printed out of a catalogue… Horrible awful little words to stop us saying what we really had to stay.

“I think we should do this kind of quickly,” Achi said finally and in a breathtaking instant her right hand was behind her back. I slipped my small object out of my bag, clenched it in my hidden fist.

“One two three,” Achi said. We opened our fists.

A nazar: an Arabic charm: concentric teardrops of blue, white and black plastic. An eye.

A tiny icon of Dona Luna: black and white, living and dead.

Then I saw Achi again. I was up in Meridian renting a data crypt and hunting for the leanest, freshest, hungriest law firm to protect the thing I had realised out on Lansberg. She had been called back from Twe to solve a problem with microbiota in the Obuasi agrarium that had left it a tower of stinking black slime.

One city; two friends and amors. We went out to party. And found we couldn’t. The frocks were fabulous, the cocktails disgraceful, the company louche and the narcotics dazzling but in each bar, club, private party we ended up in a corner together, talking.

Partying was boring. Talk was lovely and bottomless and fascinating.

We ended up in bed again, of course. We couldn’t wait. Glorious, impractical 1950s Dior frocks lay crumpled on the floor, ready for the recycler.

“What do you want?” Achi asked. She lay on her bed, inhaling THC from a vaper. “Dream and don’t be afraid.”

“Really?”

“Moon dreams.”

“I want to be a dragon,” I said and Achi laughed and punched me on the thigh: get away. “No, seriously.”

In the year and a half we had been on the moon, our small world had changed. Things move fast on the moon. Energy and raw materials are cheap, human genius plentiful. Ambition boundless. Four companies had emerged as major economic forces: four families. The Australian Mackenzies were the longest established. They had been joined by the Asamoahs, whose company Aka monopolised food and living space. The Russian Vorontsovs finally moved their operations off Earth entirely and ran the cycler, the moonloop, the bus service and the emergent rail network. Most recent to amalgamate were the Suns, who had defied the representatives of the People’s Republic on the LDC board and ran the information infrastructure. Four companies: Four Dragons. That was what they called themselves. The Four Dragons of the Moon.

“I want to be the Fifth Dragon,” I said.

The last things were simple and swift. All farewells should be sudden, I think. I booked Achi on the cycler out. There was always space on the return orbit. She booked me into the LDC medical centre. A flash of light and the lens was bonded permanently to my eye. No hand shake, no congratulations, no welcome. All I had done was decide to continue doing what I was doing. The four counters ticked, charging me to live.

I cashed in the return part of the flight and invested the lump sum in convertible LDC bonds. Safe, solid. On this foundation would I build my dynasty.

The cycler would come round the Farside and rendezvous with the moonloop in three days. Good speed. Beautiful haste. It kept us busy, it kept us from crying too much.

I went with Achi on the train to Meridian. We had a whole row of seats to ourselves and we curled up like small burrowing animals.

I’m scared, she said. It’s going to hurt. The cycler spins you up to Earth gravity and then there’s the gees coming down. I could be months in a wheelchair. Swimming, they say that’s the closest to being on the moon. The water supports you while you build up muscle and bone mass again. I can do that. I love swimming. And then you can’t help thinking, what if they got it wrong? What if, I don’t know, they mixed me up with someone else and it’s already too late? Would they send me back here? I couldn’t live like that. No one can live here. Not really live. Everyone says about the moon being rock and dust and vacuum and radiation and that it knows a thousand ways to kill you, but that’s not the moon. The moon is other people. People all the way up, all the way down; everywhere, all the time. Nothing but people. Every breath, every drop of water, every atom of carbon has been passed through people. We eat each other. And that’s all it would ever be, people. The same faces looking into your face, forever. Wanting something from you. Wanting and wanting and wanting. I hated it from the first day out on the cycler. If you hadn’t talked to me, if we hadn’t met…

And I said: Do you remember, when we talked about what had brought us to the moon? You said that you owed your family for not being born in Syria – and I said I wanted to be a dragon? I saw it. Out in Lansberg. It was so simple. I just looked at something I saw every day in a different way. Helium 3. The key to the post oil economy. Mackenzie Metals throws away tons of helium 3 every day. And I thought, how could the Mackenzies not see it? Surely they must… I couldn’t be the only one… But family and companies, and family companies especially, they have strange fixations and blindesses. Mackenzies mine metal. Metal mining is what they do. They can’t imagine anything else and so they miss what’s right under their noses. I can make it work, Achi. I know how to do it. But not with the Mackenzies. They’d take it off me. If I tried to fight them, they’d just bury me. Or kill me. It’s cheaper. The Court of Clavius would make sure my family were compensated. That’s why I moved to Vorontsov rail. To get away from them while I put a business plan together. I will make it work for me, and I’ll build a dynasty. I’ll be the Fifth Dragon. House Corta. I like the sound of that. And then I’ll make an offer to my family – my final offer. Join me, or never get another cent from me. There’s the opportunity – take it or leave it. But you have to come to the moon for it. I’m going to do this, Achi.

No windows in moon trains but the seat-back screen showed the surface. On a screen, outside your helmet, it is always the same. It is grey and soft and ugly and covered in footprints. Inside the train were workers and engineers; lovers and partners and even a couple of small children. There was noise and colour and drinking and laughing, swearing and sex. And us curled up in the back against the bulkhead. And I thought, this is the moon.

Achi gave me a gift at the moonloop gate. It was the last thing she owned. Everything else had been sold, the last few things while we were on the train.

Eight passengers at the departure gate, with friends, family, amors. No one left the moon alone and I was glad of that. The air smelled of coconut, so different from the vomit, sweat, unwashed bodies, fear of the arrival gate. Mint tea was available from a dispensing machine. No one was drinking it.

“Open this when I’m gone,” Achi said. The gift was a document cylinder, crafted from bamboo. The departure was fast, the way I imagine executions must be. The VTO staff had everyone strapped into their seats and were sealing the capsule door before either I or Achi could respond. I saw her begin to mouth a goodbye, saw her wave fingers, then the locks sealed and the elevator took the capsule up to the tether platform.

The moonloop was virtually invisible: a spinning spoke of M5 fibre twenty centimetres wide and two hundred kilometres long. Up there the ascender was climbing towards the counterbalance mass, shifting the centre of gravity and sending the whole tether down into a surface-grazing orbit. Only in the final moments of approach would I see the white cable seeming to descend vertically from the star filled sky. The grapple connected and the capsule was lifted from the platform. Up there, one of those bright stars was the ascender, sliding down the tether, again shifting the centre of mass so that the whole ensemble moved into a higher orbit. At the top of the loop, the grapple would release and the cycler catch the capsule. I tried to put names on the stars: the cycler, the ascender, the counterweight; the capsule freighted with my amor, my love, my friend. The comfort of physics. I watched the images, the bamboo document tube slung over my back, until a new capsule was loaded into the gate. Already the next tether was wheeling up over the close horizon.

The price was outrageous. I dug into my bonds. For that sacrifice it had to be the real thing: imported, not spun up from an organic printer. I was sent from printer to dealer to private importer. She let me sniff it. Memories exploded like New Year fireworks and I cried. She sold me the paraphernalia as well. The equipment I needed simply didn’t exist on the moon.

I took it all back to my hotel. I ground to the specified grain. I boiled the water. I let it cool to the correct temperature. I poured it from a height, for maximum aeration. I stirred it.

While it brewed I opened Achi’s gift. Rolled paper: drawings. Concept art for the habitat the realities of the moon would never let her build. A lava tube, enlarged and sculpted with faces, like an inverted Mount Rushmore. The faces of the orixas, the Umbanda pantheon, each a hundred metres high, round and smooth and serene, overlooked terraces of gardens and pools. Waters cascaded from their eyes and open lips. Pavilions and belvederes were scattered across the floor of the vast cavern; vertical gardens ran from floor to artificial sky, like the hair of the gods. Balconies – she loved balconies – galleries and arcades, windows. Pools. You could swim from one end of this Orixa-world to the other. She had inscribed it: a habitation for a dynasty.

I thought of her, spinning away across the sky.

The grounds began to settle. I plunged, poured and savoured the aroma of the coffee. Santos Gold. Gold would have been cheaper. Gold was the dirt we threw away, together with the Helium 3.

When the importer had rubbed a pinch of ground coffee under my nose, memories of childhood, the sea, college, friends, family, celebrations flooded me.

When I smelled the coffee I had bought and ground and prepared, I experienced something different. I had a vision. I saw the sea, and I saw Achi, Achi-gone-back, on a board, in the sea. It was night and she was paddling the board out, through the waves and beyond the waves, sculling herself forward, along the silver track of the moon on the sea.

I drank my coffee.

It never tastes the way it smells.

My granddaughter adores that red dress. When it gets dirty and worn, we print her a new one. She wants never to wear anything else. Luna, running barefoot through the pools, splashing and scaring the fish, leaping from stepping stone, stepping in a complex pattern of stones that must be landed on left footed, right-footed, two footed or skipped over entirely. The Orixas watch her. The Orixas watch me, on my veranda, drinking tea.

I am old bones now. I haven’t thought of you for years, Achi. The last time was when I finally turned those drawings into reality. But these last lunes I find my thoughts folding back, not just to you, but to all the ones from those dangerous, daring days. There were more loves than you, Achi. You always knew that. I treated most of them as badly as I treated you. It’s the proper pursuit of elderly ladies, remembering and trying not to regret.

I never heard from you again. That was right, I think. You went back to your green and growing world, I stayed in the land in the sky. Hey! I built your palace and filled it with that dynasty I promised. Sons and daughters, amors, okos, madrinhas, retainers. Corta is not such a strange name to you now, or most of Earth’s population. Mackenzie, Sun, Vorontsov, Asamoah. Corta. We are Dragons now.

Here comes little Luna, running to her grandmother. I sip my tea. It’s mint. I still loathe mint tea. I always will. But there is only mint tea on the moon.

The Fifth Dragon copyright © 2014 Ian McDonald