Raymond Electromatic—the world’s last robot—is good at his job, as good as he ever was at being a true Private Investigator, the lone employee of the Electromatic Detective Agency—except for Ada, office gal and super-computer, the constant voice in Ray’s inner ear. Ray might have taken up a new line of work, but money is money, after all, and he was programmed to make a profit. Besides, with his twenty-four-hour memory-tape limits, he sure can keep a secret.

When a familiar-looking woman arrives at the agency wanting to hire Ray to find a missing movie star, he’s inclined to tell her to take a hike. But she had the cold hard cash, a demand for total anonymity, and tendency to vanish on her own. Plunged into a glittering world of fame, fortune, and secrecy, Ray uncovers a sinister plot that goes much deeper than the silver screen—and this robot is at the wrong place, at the wrong time.

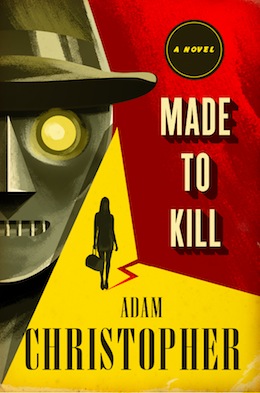

Made to Kill is the first book in a new trilogy, a thrilling new speculative noir from novelist and comic writer Adam Christopher—available November 3rd from Tor Books!

1

Tuesday. Just another beautiful morning in Hollywood, California. The sun came in through the window behind me. It was always sunny. It had been sunny for as long as I could remember.

Which currently was about two hours, ten minutes, and a handful of seconds not worth mentioning.

I sat at the table in the computer room. I was reading the Daily News. Around me Ada clicked and her lights flashed and her tapes spun. We were killing time while we waited for a job to come in. It was August 10, 1965. I knew that was the date because it was printed across the top of the newspaper in a very convenient manner.

There was a headline splashed all the way across the front page and the article that went with it was all about a film called Red Lucky. That got my attention. Movies, even in this town, rarely merited such prime newspaper real estate. I was obliged, I felt, to keep reading just to see what all the hoopla was.

“Listen to this,” I said.

Ada made a sound like she was putting out a cigarette in an ashtray that was in need of emptying, and then the sound was gone. If it had ever been there in the first place.

“If it’s about President Kennedy and his trip to Cuba, I’m not interested,” she said. Her voice came from somewhere near the ceiling. I wasn’t quite sure where exactly. I was sitting right inside of her.

I frowned, or at least it felt like I did. I scanned the front page again and saw what she was talking about: a piece—relegated to the bottom half—that was a lot of hot puff about Kennedy’s weeklong visit to Havana and how well the negotiations were going to put some good old American-made nuclear missiles down there. Just in case. After reading it I wasn’t quite sure whether I was supposed to hang a Stars and Stripes out of the office window or not.

Huh. Ada was right. When all was said and done, world affairs were a little beyond my interests, too.

“So,” I said, “do you want to hear about this cinematic marvel of the modern age or not?”

“Sure, why not?”

I found my place and I started reading. It was pretty interesting, actually. This was no ordinary movie—Red Lucky not only had an A-list cast assembled from across different studios, which I figured was quite something given most studios seemed to be at each other’s throats most of the time with their actors tied up in exclusive contracts as tight as Ada’s purse strings, but was going to be the first national film premiere, the picture beamed into theaters all over the country thanks to some new development in cinematic magic. The red-carpet premiere was due to be held at Grauman’s Chinese Theatre this coming Friday, but regular folk could grab a ticket and popcorn and take up space in theaters in twenty cities stretching from here to New York.

Seemed like a neat idea. I wondered if Ada could maybe give me the night off and I could go take a look. There were three other theaters in LA alone hosting the opening night beam-in. Couldn’t hurt to ask so that’s what I did.

“It’s been quiet, Ada,” I said, then I stopped as I wondered if it really had been quiet or whether that was just me not remembering being busy, but I’d started my query so I decided to finish it. “And if it’s quiet I think I should be allowed to go to the movies. It’s not like I need to be on call. We don’t get much in the way of lastminute assassination requests.”

At this Ada laughed and for a moment I saw an older woman with big hair leaning back in a leather chair with her stockinged feet up on a wooden desk and a cigarette burning toward the fingers of her right hand.

And then it was gone and I was back in the office, surrounded by a computer and miles of spinning magnetic tape.

The image was just an echo. Something ephemeral inherited from Thornton, most like.

“It has been quiet, that’s true,” said Ada. “Call it a lull. But I’ve got my ear to the ground, don’t you worry your pretty little tin head.”

My head was steel and titanium and I was about to point that out when Ada laughed again like a twenty-a-day smoker and said something about lightening up. Except I wasn’t listening. Something else had my attention.

There was someone in the outer office.

“There’s someone in the office,” I said, and Ada stopped laughing. On my left a tape stopped and then spun back in the opposite direction. I knew what that meant. Ada was thinking.

I turned up my ears and had a listen. I heard a pair of feet stepping lightly on the rug out in the other room, and I heard the creak of leather, like someone was squeezing a big bag. And then there was a thunk, dull and heavy, like someone was putting something dull and heavy down on the floor.

“Hello?” asked the someone. Her voice was quiet and uncertain and breathy.

I looked up at the ceiling. I wasn’t sure where Ada’s eyes were, exactly, but that seemed like a good enough bet.

“Well?”

Ada’s tapes spun. “Well, go see what she wants and then get rid of her.”

“Okay.”

“And by ‘get rid of her,’ I mean show her the door rather than the Pearly Gates, okay?”

I stood up and put the paper down on the table. “Hey, I only kill for money, remember?”

Ada laughed. “Oh, I sure do, honey.”

I walked across the computer room and reached for the door to the office and opened it and stepped through and then closed the door after me.

2

The girl was maybe twenty and perhaps not even that, and when she saw me she took a few steps backward and her eyes crinkled at the corners, like she realized this was a bad idea and that she’d come to the wrong place and things were not about to go in her favor.

Which is the reaction I get, much of the time. Most folk know about robots. Some folk over a certain age even remember them, the way we directed traffic and collected bus tickets and took out the trash. But most folk, whether from personal experience or not, don’t much like the idea of robots.

See, ten years ago, maybe more, the big rollout of robots—a joint effort between the federal government, local authorities, and private enterprise—was heralded as the dawn of a new scientific age. And this new scientific age was a really great idea for a while. People liked it.

And then they stopped liking it.

There were two reasons. One, that the jobs we—well, they—started taking, even the jobs that were menial or unpleasant or were attached to a certain kind of risk that was liable to send a man to his grave earlier than hoped for, those were jobs that people actually really did want to do. The machine men built to ease the burden of labor of those built out of flesh and blood were not welcomed but resented. Or maybe it wasn’t the robots that were resented, but the men who designed and built them.

Whatever the case, the resentment turned into something altogether nastier. Dangerous, even. That new golden dawn got a little cloudy, and quick.

And two, it turned out robots that looked almost but not quite like people were actually a little creepy. People just didn’t like them, and some people went so far as to say they’d rather have a conversation with their toaster oven than one of us. From my own experience it seemed to be about fifty-fifty: I was viewed with either a quiet and cautious curiosity, or with a healthy dose of fear and disgust. Then again, being the last robot in the world, maybe I had it a little easier than my electromatic ancestors.

But put the two unexpected attitudes together and what you got wasn’t quite robophobia, but it was close enough. The United States Department of Robot Labor canceled the program. All robots in public and private employ were immediately recalled and junked.

The grand experiment was over.

And then along came me.

I was planned as a new class of machine, a grand experiment myself. More human, on the inside anyway, with a personality based on a real human template. I was created by a guy called Professor C. Thornton, Doctor of Philosophy. He used himself as the template because I figure maybe nobody else felt like volunteering. It worked, too, but it was too late. The day I was activated in Thornton’s government lab was the day the DORL shut down. I was the last robot in the world, in more ways than one.

How Thornton managed to keep the Feds away from my off switch, I don’t know. Maybe I was a lab experiment worth watching. Maybe Thornton had spent way too much money that wasn’t his on me and the computer I was paired with. He called the computer Ada and she had a personality template of her own. I never found out whose and I didn’t care to know. She and I were a team and we were part of this new electronic world Thornton was dreaming of, one that was different from the last attempt. He gave me a program and he gave Ada instructions and he gave the both of us an office in Hollywood.

The Electromatic Detective Agency was born.

Little did Thornton know what his final creations were capable of.

The girl standing in the office took another step backward. And she was just that, a girl, and the way she reacted I could see she knew what a robot was but she’d never actually seen one. But if that was her intention, she’d come to the right place, because I was the last one there was and I didn’t even charge admission.

“Can I help you, ma’am?” I asked. It felt stiff. I was out of practice a little. Ada got the jobs. I was just the hired help.

The girl took yet another step back and the bag, which she had picked up again after dropping it the first time, dropped a second time with the same heavy sound. It was a sports bag, an arch of warm brown leather that curved up nearly to her knees, the kind of expensive but well-made bag that you’d take to a fancy athletics club where the sweat you got on was from the sauna and rather than play squash you’d sit in easy chairs as soft as warm butter and blow bubbles and talk about exotic sports that had accents over the letters.

The girl was dressed in a red dress that ended well above her knees and she had a matching red knit top. She was a dark brunette with assistance and her hair was cut into a bob, all big business at the top and back and with short bangs at the front straight enough to cut bread. There were gold bangles on both arms. Her shoes were gold-colored leather and her legs, the majority of which were on proud display, were on the inside of pitch-black tights.

I thought I knew her from somewhere, but I couldn’t place it.

This was not an uncommon feeling.

The girl didn’t say anything, she just stood there and looked at me with big eyes ringed with enough black to make her look like Cleopatra—if Cleopatra shopped at the finer boutiques of Beverly Hills.

But she didn’t answer my question so I moved to the desk and made a thing of brushing the dust off of it, and then I pulled the chair out from behind it and wondered if I should sit down or not.

I decided to keep standing and thought awhile on the best way to break the ice when she finally opened her own mouth and said the following:

“I want to hire you.”

I frowned. Or at least it felt like I frowned. My face was bronzed steel and didn’t have any parts that could move. The girl clutched her hands in front of her and had her eyes on my optics. Behind her the outer office door was closed, but on the back of the frosted glass I could still see my name and former business as clear as day, rendered in gold stencil.

RAYMOND ELECTROMATIC

LICENSED PRIVATE DETECTIVE

Now, thing was, the sign was technically correct. I was still a licensed private detective. Hell, the license was welded to my chest under my shirt. Given the intricacies of trying to show that when the job required it, I had a smaller one sewn into a leather wallet that I kept in my right inside jacket pocket. It was still sitting in there too, even though I didn’t take it out much in my current line of work, unless it was as a useful piece of cover.

Because while I might have been a private detective once, I wasn’t anymore. Only trouble was that I couldn’t much tell her what my new job was. You know how it goes, the whole “if I tell you I’ll have to kill you” bit.

Only in my case, that pithy little one-liner was right on the money. Because I wasn’t a private detective anymore.

I was a hit man. Well, hit robot, but I thought that particular hair was best left unsplit.

And the reason I was a hit man and not a private detective was a pretty simple one: killing people paid better. That’s what Ada was programmed to do. She was, at the heart of it, a business computer, one designed to run the Electromatic Detective Agency at a profit. That profit was needed because that was part of Thornton’s grand experiment—this was a robot and his control computer, going out there into a big wide world on their own, independent of any aid, federal or otherwise.

Which boils down to this: a robot has to make a living, right?

And then one day, Ada came up with a new business plan, all on her own. I tell you, Professor Thornton—rest his soul—would have been proud. Because Thornton was good. A genius. He programmed us well. The Electromatic Detective Agency was a success and even the shadow of robophobia proved to be useful. Word got around that I was good at my job—good enough that even those wary of hiring a machine were won over. And when I was actually out on the job, the tendency of half the population to instinctively look the other way just because I was a robot meant I could get on with detecting without drawing too much attention.

Maybe that was what gave Ada the idea in the first place. I don’t know. I’ve never asked her about it.

That thing about a robot having to make a living? I didn’t say it had to be an honest one, now did I?

I looked at the door and then back at the girl and I think she noticed and she shuffled and looked down at the bag at her feet. Now she was the one waiting for a response.

“Look, lady, I’m not available,” I said, not referring to either profession in particular. “You should have called for an appointment.” Ada handled the telephone and I knew she would have told the girl to come back in six months if she still needed us. That was usually enough to put people who were looking for a private detective off and if it wasn’t then Ada just gave the spiel when they called again. It was even the exact same recording.

“There’s a famous movie star. His name is Charles David,” said the girl, and then she stopped like that explained everything. I paused and looked back at the chair as I stood beside it. I pushed it a little on its swivel.

I had my instructions. “Lady, this is Hollywood, California. Movie stars tend to accumulate in this town, whether they have two first names or not.”

“I want you to find him,” said the girl.

I held up a hand to tell her I didn’t want to hear any more. My hand was made of bronzed steel and compared to the normal kind of hand made of flesh and blood I guess it was a little big. Her blackringed eyes fell on it when I lifted it up and they stayed on it when I put it down. Her lips parted a little like she was nervous.

In the other room, Ada’s computer banks clattered and beeped and the tapes spun and spun. The girl’s eyes wandered in that direction, but it didn’t matter. From out here Ada sounded like a secretary typing up a letter.

“Look—” I said as the start of a perfectly good sentence that was going to involve a polite request to go jump in a lake. But what she said next stopped me in my tracks.

“And then I want you to kill him,” she said and she said it calmly like she was ordering a roast beef sandwich from the deli down the road.

I stood there and felt my circuits fizz.

On my desk were a big leather-edged blotter and an inkwell with no ink and a telephone. I moved my hand toward the last item about a second and a half before it began to ring. The girl watched me as I picked up the handset.

“Excuse me,” I said to her, and then I said “Hello?” into the mouthpiece even though I knew exactly who it was. The phone clicked and hissed. The line was dead, of course.

“Get rid of her, Ray.”

Ada.

I tucked my chin into my chest. I almost wished I had my hat on because then I could have pulled it down. Instead I cupped one hand around the mouthpiece and spoke low and kept one optical on the girl.

“Ah, hi there. Look, about that—”

“This is not how we get jobs, Ray!”

“Yeah, I know that.”

“I get the jobs. I give them to you. That’s how it works.”

“Yeah, I know that, too.”

“Our business is a private one, Ray. People don’t just walk in off the street to take out a contract on someone. I have contacts. I have a chain. I have methods, Ray, that keep us and what we do secret to Mr. Joe Q. Public. Whoever she is, she knows what we do. She knows you’re not a detective. She knows where the office is. All of this adds up to trouble.”

“I agree.”

“So get rid of her.”

“Wait,” I said. “Do you mean—?”

“Self-preservation, Ray. Self-preservation.”

The girl was still looking at me. I zoomed in a little on the pulse in her neck and I started counting. It was fast. Too fast. I checked her pupils. They were a little small but seemed to be working. She was nervous, that was all. I didn’t blame her. She’d made a mistake, and maybe now she knew that.

Because I couldn’t let her leave the office. Not while she was still breathing, anyway.

Then she lifted herself up on her toes, like she was waiting for a long-lost love to step off a train. “I can pay,” she said.

Ada went quiet. I didn’t say anything either.

The girl bent over and picked up the leather athletic bag. She did it with both hands, and even then the bag stretched what muscles she had in her arms to their limit. She swung the bag low to the ground, like it was filled with solid gold bars. Then she puffed her cheeks out and brought it up onto the desk in one single movement.

Ada ticked in my ear like the second hand of a fast watch. “Ray…”

I held the phone away from my mouth and I looked at the girl. She was standing back from the desk, hands clasped in front of her.

“Ray!”

I brought the phone up again. “Okay, okay,” I said. Then I moved it back down and nodded at the girl. “Look, lady, this isn’t how it works—”

The girl didn’t speak. What she did was step back up to the desk and reach forward to unzip the bag. Then she pulled back the edges so I could get a good look at the contents.

I looked. As I looked there was a pause in the clattering sound from the computer room.

Inside the bag were solid gold bars. Maybe two dozen of them. They weren’t the usual kind, the kind of long, fat gold bricks that sat happily in the vaults of Fort Knox. These were about the size and shape of playing cards—if playing cards were half an inch thick and made of gold. Easier to move around than normal bars, but a bag full of them still had to weigh a hundred pounds, if not more. The girl was small, too. How she had even gotten the bag up the stairs I didn’t know, but it must have been slowly.

The clattering from the computer room started up again.

“I said I can pay,” said the girl.

I said nothing.

“I’m listening,” said Ada inside my head.

3

We sat opposite each other, me behind the desk in the chair that was specially reinforced, her in the chair on the other side. She sat perched on the edge and she kept her knees together and her hands clasped on her knees.

Whoever she was, she had some kind of training. Finishing school at least. Something else, too. Her clothes were not flashy but they were expensive. Designer. Likewise the hair. Likewise the makeup. I figured the Egyptian princess look was part of it. Nothing about her was accidental.

I wondered who she was, because she hadn’t said. In fact, she’d refused to say an awful lot, so far anyway.

I considered again. Neither of us had spoken in four minutes and fifty seconds and those seconds just keep ticking on.

I hadn’t said yes to the job yet, either. Just getting information out of her felt like a case in itself. She was fighting me and she wasn’t even trying to hide it.

“So how do I get hold of you?” I asked.

“You don’t,” she said, nothing moving except her lips. Then she blinked and she adjusted her fingers. “I’ll call every day until you have something to tell me.”

I shook my head. She just blinked at me again.

“I’m going to need a name,” I said.

Her mouth twitched. “You have it already.”

I simulated a sigh, on the inside. Ada was listening in from the computer room. I wondered what she made of it all.

“The name I’m looking for is yours.”

She shook her head. It was just two moves, one left, one right, and her hair swung in the same direction.

“You don’t need my name,” she said. “I’ve paid up front. I’ll call every day. You just need to find Charles David and eliminate him.”

Eliminate. Interesting choice of word. It made Charles David sound less like a person, more like a problem. Which was exactly why she’d chosen to use it now we were talking business talk.

Charles David. Movie star. Big time, apparently. If I’d known who he was once, I didn’t know now. Being a robot had certain limitations, chief among them being one simple yet important fact.

I couldn’t remember a damn thing.

Inside my chest was a memory tape. It was a work of art, an act of miniaturization that would count as a scientific miracle if only it were used in more than just me. Still, it was something my creator was proud of inventing. But squeezing so much portable storage into such a small space was difficult and while Professor Thornton managed to do it, it came with a cost: the tape could only hold twenty-four hours of data before it came to the end of the spool and needed switching out for a new one. The old memory tapes—years’ worth of the things—were stored in a room hidden behind a concealed door on the other side of the office. That room was pretty big. Or I thought it would be pretty big.

I didn’t remember.

So every day I needed a new, blank tape. I was still me—my electromatic brain ran off of a template of Professor Thornton’s mind that was hardwired into my circuits, and there were plenty of basics I had on permanent silicon storage: I knew how to speak English, who Ada was, that I lived in Hollywood, California, and that the capital of Australia was Canberra.

Actually, I wasn’t sure about Canberra, and now that I thought about it my knowledge of Australia was fuzzy at best.

Otherwise? Poof. All gone. A pain in the ass for detective work, let me tell you. At least I had Ada to keep track of everything that I couldn’t.

But for my new job? Actually, not remembering things was a nice little safety net. One we’d never had to test, of course, but still. As Ada said, ours was a private business.

So when I looked at the photo that the girl had produced not from the leather bag but a pocket on the front of her dress, I wouldn’t have been able to tell you that it was of the famous star of the silver screen, Charles David.

The photo was color and the party on it was a sturdy-looking fellow with red-blond hair that was starting to thin on top but was still ample enough to make an effort with. He had a red beard with flecks of gray in it that were nicely symmetrical. The beard was well groomed but it was bigger than typical. The bottom of the thing touched at least the second button of his shirt below the neck.

Charles David was looking somewhere out of shot with an expression best described as wistful and that was rarely seen, so I imagined, outside of the confines of a movie star publicity shot.

As I took in the view of the target my mysterious client spoke.

“Do you want this job or not?”

I sighed on the inside. Ada kept on typing in the other room.

“I’m going to need more than a photograph,” I said. “Maybe you don’t know how this works, and I’d say that’s a good thing. Nobody should, not really. I’m just providing a service that sometimes people decide they require. That’s none of my business. But if I’m going to carry out this job to the satisfaction of the both of us, I need information. Data. Remember, you’re talking to a walking computer bank. You need to feed me the right kind of information if you want the right kind of result.”

The girl’s pulse was racing. She looked unsteady on the edge of the chair. I wanted to tell her to plant herself on it properly and was about ready to get up and help her off the floor when she seemed to snap out of it.

“Look,” I said. “You said Charles David is missing. Why is he missing?”

“I… I don’t know. He just is.”

I shook my head. “He just is.”

“I can give you an address.”

“That’s a start.”

“That’s all I can give you.”

I ground something inside my workings. It sounded like a car trying to start on a cold winter’s morning.

“That and the payment,” she said. She stood up and reached over the desk. From the same pocket the photo had come from she pulled a mechanical pencil and she used it to write something on the blotter in front of me. I watched her write it. Then I watched her stand up and put the pencil away.

I looked at the address. It didn’t mean anything to me.

“Where did you get the gold from?” I asked.

Instead of giving me an answer, she said, “I’ll call tomorrow.” And then she was gone and I was left steering the desk.

The telephone rang. I picked it up.

“I guess our quiet patch has come to a conclusion,” said Ada.

I rubbed my chin. The sound of steel rubbing steel was irritating, even to me, so I stopped. Another of Thornton’s mannerisms, no doubt.

Huh. Thornton. It was a shame about him, and that was a fact.

“Ray?”

I snapped out of it and dropped my hand to the desk. “I don’t like it,” I said.

“She paid up.”

I looked at the athletic bag. It was still on the desk. It was still open. I reached forward and peeled the edge back like I expected the bag to be full of snakes. It was still full of gold. Lots of it. I reached in and picked up a bar.

The ingot was perfect. I turned it over in my hands, recognizing the dull yellow sheen that the twenty-four-carat stuff had and that didn’t look quite real. I turned the ingot over and over again. It wasn’t marked. No stamp, no etching, no hallmark. I didn’t think that was right. It might even have been illegal. The small thin bar was gold and nothing but. I squeezed it a little between two fingers and made a little dent, like the thing was butter fresh out of a very cold refrigerator.

“Where did she get it from?” I asked.

Ada hissed like a middle-aged woman rocking back in an office chair with the late afternoon sun coming in through the blinds behind her might hiss.

“Doesn’t matter. She’s paid up. This looks like our most profitable job yet.”

I wasn’t so sure and I said so.

“Raymondo, you worry too much.”

“And you don’t worry enough, Ada.”

“What was that I said about lightening up, Ray?”

“Part of what worries me,” I said, “is that you’re not worried.”

“Gold is clever, Ray.”

I put the ingot down on the desk and eyed it and then I sat back in the chair. It creaked. “I get it,” I said. “Unmarked, untraceable. Gold is gold is gold.”

“Could be a bag full of melted pocket watches, all we know.”

I sniffed. It sounded like a Lincoln Continental with a dead battery. “That’s a lot of pockets.”

“The only thing we know for sure, Chief,” said Ada, “is that she’s paid us for a job, which means we’d better get to it.”

I had a vision of Ada relaxing and taking a long drag on a long cigarette, not a care in the world.

I looked at the gold. I looked at the bag. I wondered how much it was all worth. It bothered me quite a lot and I said so.

“Easy, Ray.”

“Someone might want it back,” I said.

There was a pause and a ticking sound.

“Go on,” said Ada.

I levered the chair back to the upright and kept going, reaching for the gold ingot and holding it up between an articulated forefinger and thumb. I turned around in the chair. There was a window behind me, a big one, and it was full of sunlight. So I held the bar up to that sunlight. I wasn’t sure what that was going to tell me but I was looking for options. The bar glinted a little, but not a lot.

“The gold isn’t hers,” I said. “I mean, not personally. It can’t be. Nobody keeps gold like this.”

“Lots of people keep gold,” said Ada. “Governments, for example.”

“And big banks and Fort Knox,” I said. “Yes, I get it. But not like this. And not regular people.”

“So she isn’t regular people.”

I considered. Maybe Ada had a point. The girl had been young and pretty, dressed casually but in expensive gear and she had expensive hair. The bag itself, even without the gold stretching the seams, was top drawer. She wasn’t short of funds.

She had also been strange. No name. No conversation. She was afraid but calm at the same time. If it was an act, it was a good one. She’d kept her cool.

But it still didn’t fit. People didn’t have gold. Which meant she got it from somewhere. And the way she acted, I figured she didn’t want anyone to know she’d come calling.

Which meant the gold not only wasn’t hers, she’d taken it without permission.

Our mystery girl was a thief and that’s what I said to Ada.

“She’s also our client now, Ray,” said Ada. “And she’s paid in advance.”

“Someone might want it back,” I said again, making sure Ada hadn’t conveniently wiped over that part of the conversation on her great big magnetic memory tapes in the other room.

“Ray, don’t tell me Thornton programmed you with a conscience?”

I laughed. I’d been practicing. It sounded like two rocks going for a joyride in a clothes washer.

“Maybe he did,” I said. “You know I think about him, sometimes.”

For a moment it felt like Ada took a drag on a cigarette, and then the image was gone.

“Yeah,” she said. “That was a terrible accident he had.”

“It was.”

“Very sad.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Don’t worry. We sent flowers.”

“Good.”

“And you should keep your mind on the job, Chief. She gave an address. You should go take a look.”

“Okay,” I said. I lifted the hat from my desk and I stood up. I kept a firm grip on the telephone because something was bothering me.

“The girl…” I said.

“What about her?”

“She knew about me. She knew where to come.”

“These are true facts.”

“I’m going to have to find her and kill her, too, aren’t I?”

“At least she paid in advance.”

“Seems a shame.”

“She made the choice to come here, Chief. We are obliged to take precautions.”

Ada was right and I knew she was right but I still thought about it for a few seconds as I stood by the desk.

“First things first,” said Ada. “You’ve got work to do.”

I frowned. Then I hung up the phone and put on my hat and made sure it was straight. And then I headed out the door and locked it behind me.

Excerpted from Made to Kill © Adam Christopher