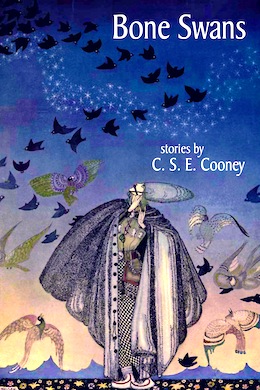

Bone Swans by C. S. E. Cooney is the most recent publication from Mythic Delirium Books—run by Mike and Anita Allen, of the similarly named Mythic Delirium magazine—and joins a small slate of other works under their purview, such as the well-received Clockwork Phoenix anthologies. This original collection contains five stories, one of which is published here for the first time (“The Bone Swans of Amandale,” from which the book takes its title). Plus, it has an introduction by none other than Gene Wolfe.

Though in the past I’d say I’ve been most familiar with Cooney’s poetry, we also published a story of hers at Strange Horizons while I was editor that I (obviously) quite liked. So, I was pleased to see a collection of other pieces—none of which I’d had the chance to read before, which is actually fairly rare for me when picking up a single-author short story volume. It’s also interesting to see a book of mostly longer stories; as I said, there are only five here to fill the whole thing, two of which were initially published at Giganotosaurus and one as a chapbook.

Bone Swans is one of those rare breeds of collection that manages, though the stories aren’t connected or related, to have a fairly clear and resonant theme—or, at the least, an obvious shared thread throughout. That thread is Cooney’s particular approach to using the trappings and traditions of mythic narratives to structure her stories: each of these pieces has an obvious genetic tie to the world of myth, a place where structured magic is as real as the dirt people stand on and there is a specific and often grave logic to the consequences of our actions. However, Cooney’s approach also brings in a sort of cavalier, witty, and approachable contemporary story-telling, perhaps more closely related to adventure yarns than anything.

The result tends to be a fascinating mashup between the tropes and resonances of the mythic tale with the sensibilities of contemporary action-oriented fantasy: simultaneously lighthearted and serious, full of consequences but also ubiquitous happy endings. And these stories also treat the logic of myth, which tends to be the logic of sacrifice and ritual, as a true narrative logic. That can be refreshing and weird, considering that a great deal of the time the logic of religious or mythic plot is not the same thing as the logic of short story plot. It feels, often, like Cooney has decided to quite intentionally treat as real a form of thinking and believing that most folks have written off as made-up; fairy-tales, if you will, instead of the constitutional logic of a genuine world. Except here, it’s the real deal and it’s the thing that’s going to drive the whole story.

So, that’s fun, even if it can occasionally be dislocating. (And I can certainly see why, of all the small presses to pick up this book, it was Mythic Delirium; has a nice confluence.)

As for the stories themselves, “The Bone Swans of Amandale” was perhaps my personal favorite. It’s a riff on the Pied Piper story, told by a shapeshifting rat who’s in love with a shapeshifting Swan Princess. This one has that mythic logic, too: it’s all about sacrifices made at the right time for the right reasons, getting back things that aren’t quite what you wanted, and the very hard reality of ritual magic. The tone is irreverent and offbeat, almost too much so at points, but it works; without the protagonist’s rattishness, the story might come across as far too stuffy or overblown. Instead, the odd mix of tones makes for a fairly compelling story of magic people and magic places.

However, “Life on the Sun” is perhaps the best illustration of what I mean about the tone and construction of these stories. In it, a young woman of an oppressed people is fighting part of a guerilla revolution; however, a mysterious sorcerous army comes to the city and wipes out their captors—with the demand that she and her mother come to the king of the people. Turns out, that’s her dad; also turns out, she was quite literally marked by god as a sacrifice to bring life to the land when she was born, except her mother stole her away. This is where the story turns onto a different track than you might expect, because this is actually the truth. Her father isn’t evil or mad; her mother still loves him, and he loves them both; he’s also responsible for the lives of his people, and knows that the sacrifice has to be made willingly. He even left them alone for twenty years, until it became too much of a problem.

So, she decides to do it—she makes the sacrifice of herself. And then, through the magic and logic of sacrifice, she does not truly die but becomes the god of her people to bring rain; she also, eventually, dons her human form again to see her friends and lovers, good as new. She’s changed the mythic cycle by becoming old enough to take up the mantle of the god more knowledgably than a child could, and now, no more deaths to make rain.

It’s not a short-story-plot sort of logic; it’s a mythic logic, and it works. The balancing of that against a far more typical second-world-fantasy story of oppressed people winning back their kingdom is what makes the story read as something fresh, even if its constituent parts separately are fairly obvious. And that trend holds with other pieces as well, such as “Martyr’s Gem,” where oaths, magic, and storytelling all play a significant role in the marriage and life of our protagonist. “How the Milkmaid Struck a Bargain with the Crooked One” is a take on Rumpelstiltskin, except with a bit more romance—but the same fairytale air.

The last story, “The Big Bah-Ha,” is the one Wolfe mentions directly in his introduction; it’s an odd piece, the least directly connected to the rest in terms of its tone, but still with a touch of that old-school structure of sacrifice and magic. It was actually the one I found least compelling, though; something about the post-apocalyptic children’s world thing doesn’t work for me—pretty much ever, actually—though the idea of the Tall Ones and the reality of the afterlife kingdoms were interesting.

However, overall, this is an intriguing and readable collection—one that is, certainly, doing something rather specific and unique. I appreciated the whole mashup aesthetic of the mythic and the contemporary in terms of storytelling style, and I also just liked the pleasantness of the pieces themselves, with all of their happy endings and costs paid well for worthwhile things. Of course, a lot of mythic narratives don’t end so nicely—so perhaps that’s something I missed, on the other side of the coin—but these ones serve perfectly well.

Bone Swans is available July 7th from Mythic Delirium.

Lee Mandelo is a writer, critic, and editor whose primary fields of interest are speculative fiction and queer literature, especially when the two coincide. She can be found on Twitter or her website.