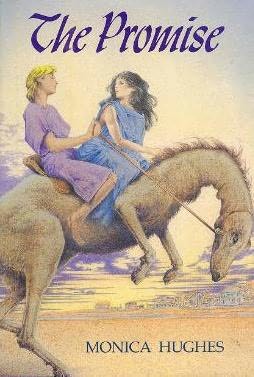

Sandwriter was enough of a success that four years later, Monica Hughes returned with a sequel, The Promise. Antia and Jodril have now escaped the desert (yay) and are living a privileged, luxurious life in the royal palace of Malan, ruling the twin continents of Kamalant and Komilant. So that’s nice.

Alas, their marriage is not going all that well, since in the intervening eleven years, Antia has discovered that when she and Jodril wrote their names in the sand at the end of the last book, they were not, as she had fondly thought, just engaging in some romantic sand art to seal their bond, but actually promising to send their first born daughter, Rania, to the Sandwriter, as soon as the girl turns ten—to live as a hermit in the desert for the rest of her life.

And Jodril is insisting they go along with this, because, they made a promise.

Wait. WHAT?

Let’s forget, for a moment, that pretty much all of the problems of the last book were caused by the decision to invite a young, spoiled princess of Kamalant and Komilant to the desert, a decision that ended up costing one person his life (granted, a manipulative, greedy, person, but still) and nearly betrayed all of Roshan’s secrets to the more powerful lands to the north. Let’s also forget asking, for the moment, what type of planetary security system makes itself dependent on parents willing to sacrifice their oldest kid, and ignore the not so small problem that absolutely nobody in the book thought it might be nice to warn Rania that this is coming. The closest thing she gets to a warning is a conversation she overhears between her parents a day before her tenth birthday—just three days before she’s sent off to the desert, like THANKS ANTIA for preparing your child.

And let’s forget that in the previous book, Antia was not only older, but also had some choice in the decision to go to Roshan.

Instead, let’s focus on what the text of the previous book specifically says about Antia’s part in this:

She looked at Sandwriter, saw the smile on the old woman’s lips. “I do not understand, but yes, I will write my name.” She knelt to write her full royal title in the sand of Roshan.

That’s it.

In other words, Sandwriter tricks Antia into giving up her first born child. At no point (I checked, and rechecked) does Sandwriter or anyone else inform Antia that she is signing away the life of her child until after Antia signs the sand, and even then, this is very vague, and phrased as if the kid will have some role in the decision making process. Antia even makes this clear: she doesn’t understand; she thinks she’s just signing her name.

In case we’re in any doubt here, Antia even reminds us of this in this book:

“A promise! What promise? I didn’t know what it meant. I would never—It doesn’t count. It can’t. It mustn’t.”

And yet, Jodril tells her that they made a promise and it must be kept because future of Rokam blah blah.

It doesn’t really help that although Antia and Jodril know full well that their daughter is Destined for Misery in the Desert, they pamper their kid for ten years, leaving her completely unsuited for the desert, though at least their wish to indulge their kid is understandable, and apart from her complete lack of desert survival and basic housekeeping skills, it doesn’t seem to have caused any long term injury—indeed, Rania proves to be far better at adjusting to different situations than her mother was in the previous book, and she comes across as a much nicer person overall. That in turn makes what happens to her all that much more painful. It also really doesn’t help that everyone who objects to this or displays disapproval just happens to be a woman. The men are all, “Well, of course. This is the way things are. Now go run along and be sacrificed.”

Hughes, of course, had made a near career of telling tales of children sent off to unfamiliar cultures, places and even planets largely against their will, in an echo of her own early life where she was shifted from country to country as her parents moved from place to place. And here, I can sympathize. I can also easily sympathize with parents—or any adults—finding themselves in over their heads, or signing a contract without being aware of the full implications of that contract. This happens all the time.

And the opening echoes endless fairy tales of parents who agreed to give up the first person to greet them at the gate if only—if only—the monster would let them go. Though, in stark contrast to those fairy tales, those parents at least knew they would be losing something—a dog, perhaps, or a servant. Antia didn’t even know that much.

But those fairy tales contain something that this story lacks: an explanation for why the parents have to keep their promise: if they don’t, they’ll get eaten. It’s a little less clear in this book. Sandwriter does, granted, have all kinds of powerful magical abilities—back on Roshan. Rania, Antia and Jodril now live in Komilant and Kamilant, several days of sailing away. It’s been established, more than once, in both books that Komilant and Kamilant are far wealthier and far more powerful. It’s also been established that Sandwriter’s main task in life is to prevent Komilant and Kamilant from gaining access to necessary resources beneath Roshan. In other words, agreeing to this isn’t even in the best interests of their kingdoms.

So, basically, a ten year old is getting sacrificed so that the people of Roshan can continue to live in poverty and deprivation and so the planet can continue to force a woman to live alone in the desert, watching a pool of water and a pool of oil, occasionally setting off sand storms.

This is not a promising start.

Anyway. Rania, determined to act like a princess, sails to Roshan in the company of Atbin, the young boy sent to fetch her. She spends three days with her grandparents before heading out to the desert—fitting in, I must say, much better than her mother did on a similar journey—and starting her apprenticeship. It’s fairly brutal: she has to give up everything, including her hair and her doll, and since the village that provides food to Sandwriter doesn’t actually increase the amount of food after she arrives, she’s also eating less. (Later, we get a fairly graphic description of the result of this: she’s underweight.) And she has endless lessons on seemingly everything: stars, plants, rocks, finding her way through dark and twisted passages. And the only person she gets to see is Sandwriter, who frequently is not the most talkative sort.

On the bright side, she starts to gain some psychic powers. So there’s that.

Her training continues for about four years, until she and Sandwriter catch a glimpse of a villager in trouble, near death. Said villager is the father of the same boy that escorted Rania to Roshan, and she begs Sandwriter to save him. This is done, but at the cost of creating some destructive weather and harming Sandwriter; there’s a lot of stuff about the consequences of actions and needing to think things through. And some unforeseen consequences: the incident encourages the villagers to finally send more food up to Sandwriter and Rania, allowing Rania to eat her fill at last, which is a good thing. It also encourages Atbin to finally send Rania a little wooden doll that he carved for the girl years back, which seems to be a less good thing: on the one hand, it’s the first thing she’s owned in four years. On the other hand, owning it seems to make her depressed and secretive, and it leads to Sandwriter deciding to exile her to a life as an ordinary girl, at least for a year, to finally give Rania a chance to choose her own life.

Only it seems that it’s already too late.

To be fair, the text is slightly unclear on this point, with page 178 offering this in the first paragraph:

“The rain gods had neatly removed every choice from her and she had only to do as they commanded.”

And in the fourth paragraph on the same page:

“When Sandwriter took off my robe and cut my hair I was reborn into my life as an apprentice. Then I had no choice. This time it is I who choose.”

I tend, however, to agree with the first paragraph, and that the second is just a comforting lie Rania is telling herself. If the last third of the book has made anything clear, it’s that Rania indeed has no choice. Her time in the desert and her training with Sandwriter has changed her so deeply that she can’t lead an ordinary life. Granted, part of this is because Rania doesn’t want to give bad news to people, and she does, indeed, choose to step back from that. But that’s only part.

This last third also gives me a touch—just a touch—more sympathy for Sandwriter’s position: as she explains, she is 76 years old when the book begins, terrified that she will die before she can train her successor—and terrified of what could happen if the planet and the Great Dune are left without a guardian. That said, I can kinda guess what would happen: Roshan would finally start using the pools of water and oil, possibly angering the rain gods, possibly not angering the rain gods, but at least not being left in a static, desert state. Based on the ordinary people we do meet, that might be a good thing, but I digress.

The Promise is not unlike Hughes’ other works, variations on the lemons/life motto: that is, when life gives you an all powerful government entity deeply oppressing you and denying you basic human rights and freedoms, create a utopia. Preferably one in primitive conditions relatively free from technology. Except that in this book, it’s not a distant, faceless government entity, but rather people who know Rania personally: her parents (however unwitting and unwilling her mother’s involvement), her grandparents, Sandwriter, and Albin. All, except for Sandwriter, at least claim to love her.

Which is what makes the book so terrifying.

In some ways, certainly, The Promise can be seen as an empowering work, where the most powerful person on the planet is an elderly woman (a nice touch) who is training a young girl to take her place. And I suppose it’s nice that the person sacrificed here starts out as a privileged princess, rather than one of the poor islanders. I also like that this shows the darker side of those fairy tales, the idea that keeping a promise made by your parents doesn’t always lead to a prince, but rather something else.

But rather than being a story about empowerment, The Promise turns out to be a story about giving in, not just to the parents that unwittingly made terrible choices on your behalf, but also to an oppressive system that demands austerity from everyone with the bad luck to be born on an island instead of a more privileged, wealthy location, and demands that a woman give up her life to maintain this system. Sure, sometimes this can happen. Sometimes accepting the bad can even be healing. But in this book, this comes marked with more than tinge of approval, that giving into this is a good thing, and that, I find harder to accept.

It seems to have been difficult for Hughes as well: her next book was to take a slightly different approach.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.