Sometimes you come across stories that are so beautiful and unsettling and weird and wonderful, stories that defy description and explanation, that you wonder why you’ve never read Kuzhali Manickavel before. A writer of short fiction (so far), who is based in Bangalore, Manickavel seems to excel at balancing strange, bizarre scenarios with turbulent, fraught emotion.

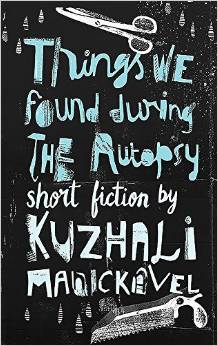

Her most recent collection of shorts, Things We Found During the Autopsy, has been published by Chennai indie press Blaft, and it’s just really, really intriguing in the best possible way.

The stories each contain a combination of anger, humour and bitterness—some more than others. Manickavel’s informal and often irreverent prose is perfectly attuned to this sort of weird fiction, often defying explanation even as it invites interpretations. She’s perfectly at ease using Hindi words and phrases alongside English, and her syntax is very often more similar to the subcontinent’s particular dialect (if I can use that word) of English. There are rules for writing in ‘proper’ English but Manickavel is not bound by them. I spoke to her over email about her writing and about how it was sometimes necessary to break the rules, especially given our colonial hangovers. ‘This language comes a lot more easily for me’, she wrote back, ‘it’s more interesting to play around with and I feel it gives me the ability to express things that I can’t say in conventional English. I think at some point I made a conscious decision to write stories that I wanted to read and I couldn’t do that until I changed the language I used.’

To give you an idea about what sort of weird fiction this is, let me tell you the six things they found during the autopsy of this nameless girl, an autopsy conducted by her friends: a Playboy magazine hidden behind her jaw, black ants floating through her skin, angels nested behind her heart that had to be pulled out with tweezers, St. Sebastian tied to her spine, typhoid in her liver, and a copy of Playgirl magazine, spread across her ribs. The friends decide this means that she must have been conflicted about her sexuality and they ‘could have been the awesome friends who held her hand while [they] dragged her out of the closet.’

The stories are different lengths, but none more than a dozen pages at most. Many are the size of flash fiction—a paragraph or maybe a page. The brevity of course is part of the attraction—each little short is a condensed pill that has a strong long-lasting effect, none are fragments. It’s quite a feat to say a lot in a few words and Manickavel agreed that it was indeed much harder to write, too: ‘I feel like I can get away with a bad sentence in a longer piece but with shorter pieces, the entire narrative is tighter and more focused so I really have to think about the story I want to tell and be honest about what elements are contributing to the story and what’s in there just because I think it’s clever. I also like to explore the words themselves, try to open them up and see the shades and layers they have and how they can change the way the story is being told.’

There really is a lot to unpack in each of these stories. It’s not just in the words, but in what’s been left unsaid. The characters resonate, humming with taut fragile humanity, each person’s neurosis close to the surface; all the things we keep hidden placed on display; each emotion, each paranoia, each insecurity brought to the surface and left floating there, often unnamed but always sharp. The writing is lyrical and always funny, with a bitter dry humour that reveals sadness lurking in corners: spiritual entitles trapped inside a young girl long to be away from the dead trapped there with them; a lonely young woman awaits roommates and imagines what she might say to them, how they may connect; two people keep a dragon in a box in their kitchen until it simply fades away; a girl throws a rock at a child from a slum, ‘like throwing rocks at dogs.’

It’s easy enough to pick up on common themes through the stories: colonialism, alienation, feminism, sexuality, economic disparity, relationships, growing up and not fitting in—but ask Kuzhali Manickavel about them and she often deflects the question. How does one ask her about all this in reference to her work and not have her avoid answering? So instead I asked her, what’s up with that? ‘I think I deflect those questions because I don’t have any answers’, she said. ‘People often ask really smart questions about these things and it seems unfair not to have a good answer for them because they are important things to me and I certainly think about them a lot. I guess there’s just a lot to say and lots of feelings and it’s hard to be coherent about all that.’ But coherency is something she achieves with her fiction. You don’t always need to spell things out—you can have a moulting angel trapped in a glass jar and a paint-peeling god in the basement and still say a great deal.

Some of the stories of course stand out more than others. One such story is the fascinating ‘The Twins’, in which a pair of twin babies feature as a sort of family heirloom, passed down between generations, ‘because we couldn’t get rid of them’. Kept in a broken wooden box filled with newspapers clippings of Ian Botham, no one knows much about them, other than their permanence and that sometimes plants grow from them, leaves curling up around their little ears.

‘I was thinking about some of the things that get passed down from generation to generation- they aren’t precious, nobody knows where they came from or why they are being passed on.’ says Manickavel, ‘and yet there’s a sort of protectiveness about these things, like it’s a secret no one else will understand. So I thought, yeah that’s interesting. Then I thought, you know what else is interesting? Baby-type things in a box that have trees growing out of them.’ That’s what’s great about these stories—they are clever and smart and funny and then suddenly, they are very surreal. Manickavel explains, ‘I think that’s how a lot of my stories come together- there is a somewhat coherent thought and then penguins stealing bicycles happens. And sometimes it’s just the penguins stealing bicycles.’

Yes, there are bicycle stealing penguins in this book too. And shape shifters and a ‘whore-raft’ made out of the floating bodies of prostitutes, immense economic disparity and fear and loneliness. Things We Found During the Autopsy is beautiful and bizarre, and always dark and deep and easy to lose yourself in. It is also, of course, hard to pin down. I’ve heard Kuzhali Manickavel be called a ’South Indian Experimental Feminist Writer’, so I asked her what that meant and her reply was what I’ve now understood to be perfectly Kuzhali: ‘I have no idea. Someone told me it’s a special kind of white dude and I was like, you’re lucky I don’t blog anymore because if I did I would blog so hard about how that’s such a racist thing to say and like, three people would retweet that shit. That shut them up pretty fast. By golly.’

By golly, indeed.

Mahvesh loves dystopian fiction & appropriately lives in Karachi, Pakistan. She reviews books & interviews writers on her weekly radio show and wastes much too much time on Twitter.