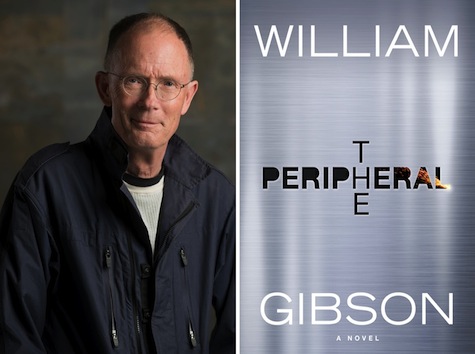

William Gibson is one of those great writers who is also a great talker; his collected interviews provide a brilliant director’s commentary on his work. In advance of the release of his new novel, The Peripheral, I talked to him by phone about London, the “raging dystopia” of rural America, urbanism and gentrification, the influences behind The Peripheral, his approach to writing science fiction, and why his own novel ended up giving him the creeps.

Spoilers for The Peripheral follow, at some length. Just so you know.

I was just recently in London and stayed at a flat right around the corner from Soho Square.

Ah, okay!

So I was amused to see it in The Peripheral, and I wanted to ask—London’s been a pretty significant location in your books recently and I was wondering if you could tell me a little more about that.

Well, London, for a number of reasons, has sort of been my other place for most of my adult life. One of the reasons is that I’m sadly monolingual. I can understand—can sort of make out the front page of a newspaper or eavesdrop on a conversation, provided it’s Mexican Spanish, but in Spain I’m totally lost. London is sort of the only place in Europe where I have the linguistic ability to sort of sync very deeply into the texture of the place. Actually all of England would, but London is—I’m lazy enough, I guess, that it’s the convenient place.

And when I began to be published, the English market, the British market was my most significant foreign market, and initially, much more enthusiastic and encouraging than the American market. So Gollancz would have me over every time I published. It became the foreign place that I most frequently visit. I always have—since I first saw it in, I think, 1971—thought it was for all the reasons an incredibly interesting place. And I think that’s why my imagination returns to it as easily as it does.

It’s become pretty interesting lately—when we were there we took a walk and ended up at the Leadenhall tower, which seems like it practically came out of your book.

Yeah. … There’s something going on, not just in London, but in a lot of cities in the world now, where it’s like they’re being—they’re being finished. And it’s like the project of urban capitalism is finally completing itself in certain cities. And it seems very easy to look at it and wonder whether this is an entirely good thing.

I’m inclined to think that … part of what we’ve traditionally valued in certain cities actually emerged from the extent to which their original function was broken, so that the heyday of a certain kind of bohemian party existence in Manhattan or London was predicated on each of those places being almost in ruins and uninhabitable by the more discerning. So that they could, in fact, fill up with talented young people, and become fantastic generators of innovation. And it looks to me that the problem is, when you finish them, if you gentrify every last bit, it kills it. It kills something, I suspect.

I remember when I first went to New York as an adult, really for the first time after I published my first story in Omni magazine. I immediately bought a plane ticket because I had to meet these people who had paid this handsome sum for 27 pages of double-spaced, and I would up staying down with friends down in Alphabet City. And I was sort of walking around looking at that and I was saying things like, “Wow, this could all be fixed up! This could be worth a fortune if somebody would just tidy it up.” And these New Yorkers were looking at me with total scorn because I didn’t get it, and they said, “No, that can’t happen! That can never happen here, this is what it is. It’s always going to be like this.” And I said, “Well, somebody could fix it. The Japanese could fix it, if you gave it to them!”

And you know, I was right! And it pretty much has all been fixed. They fixed the Bowery! It was all just waiting to be as valuable as it possibly could be. Which is great, but you don’t have the same conditions there that made it what it was. Maybe you’ve got them in Brooklyn … but I don’t know. Or maybe I’m just an old fogey. There’s a certain danger, always a certain danger in that.

I live in Austin … there’s a sense of that in some neighborhoods here, and I felt some of that in the East End of London as well.

Yeah, well, the East End—I think the East End, for most of my life, had been regarded as totally unfixable. It was just going to be that. They weren’t even going to think about trying to gentrify that. And if I were a developer, sort of rolling into a new town, the first thing I would ask is, “Okay, where is the neighborhoods that you’re absolutely positive can’t be gentrified? I’d like to see those first.”

On the other end of the spectrum, I wanted to ask about Flynne’s home town. Have you ever really used a southern small town setting in your work before? I know you have characters like Rydell [from those parts].

No, I haven’t, but I was really careful. … Initially I didn’t want it to be anywhere in particular. So it’s never named. The town’s never named, the state is imaginary insofar as all of the place names in it are made up. So you can’t tell from textual evidence what state it is except that it’s probably not Virginia, because they refer several times to “Northern Virginia”, and they wouldn’t if they were in Virginia. They’d say “up north”. And I was hoping that it would be possible to read it as they’re maybe in Pennsylvania, right across the Virginia line, which is pretty much like being in Virginia. Maybe they could be more Ozarks.

But inevitably, in spite of my wanting that, I think what happened was that my experience of my own childhood colored it all. And so it feels more like a southern small town than anything else. But it’s still there’s a way in which it’s—the landscape never fully gelled for me. I never decided [on] the countryside it’s set in, there’s a way in which it isn’t any place in particular. At least, it never was for me. If I had been consciously setting it in my home town, even if I’d called it something else, it would have been a lot more visually specific. You can’t tell really whether they live in flat land, or hills. There’s a kind of inadvertent generic quality to it that stems from that idea I had that I could make it kind of Everytown. But in the end I guess it’s not really.

For me, my mother is from deep south Alabama, and there was a sense in which that was the image I had in my mind, of that town, even if it wasn’t specifically what you were going for.

Well, that’s good, because that’s how I was hoping it would work. That people would take it to where they’re from, or where their parents are from.

[Here I got off to a bad start on a question and then, as if sensing my impending failure, the call dropped. After we got reconnected and sorted out, I tried again.]

At what point did you realize the story had to take place in that kind of a rural setting? I was also wondering—in one of your interviews you said something to the effect that SF is less about the future than the “unspeakable present”, and I guess I was wondering what about Flynne’s town, that whole middle/rural America setting, how that fits in with the present you’re writing about in The Peripheral?

Well, when I was just beginning I had this girl walking down a hill to go to see her brother who lived in a house trailer. I didn’t really have anything else at all, and I didn’t know when it was, and I was just trying to channel the feeling of this girl who was the character … and it was at the stage when I feel like the characters are kind of auditioning, and sometimes they get the role and sometimes they don’t. She definitely got the role, but the whole business of the world around her and how she lives, sort of grew out of that initial encounter. And it grew really quickly I think because it was very familiar territory in a lot of ways. It could be where Rydell from Virtual Light grew up. It’s like—it has a lot—if some of the characters from Virtual Light sort of teleported in there by accident, they wouldn’t be totally lost.

So it’s kind familiar territory that way, and since Virtual Light, there have been some really really great pop artifacts examining the rural american present as a kind of raging dystopia. The film Winter’s Bone which I think was actually—it’s been years since I’ve seen it—but I think it was a big influence on my sense of who Flynne is. The television series Justified, which goes, in a way, totally cyberpunk on that kind of social reality.

So it was kind of ready to go, and that was in real contrast with getting the further future up to speed, and that was really, really hard! Really hard work! I realized, to my chagrin, really, that I had never fully appreciated how much extra work it is, writing really high resolution SF … . The first words of fiction I wrote were trying to be high-resolution SF, so I had no idea how much more difficult it would be to be back in this part of the form where I have to make everything up, in a completely different way, and get the tone right, keep it coherent. It was kind of like [I was] privately embarrassed at how long it took me to get it to work.

It finally worked when … I gave myself permission to go into a kind of—it felt to me like almost a kind of fairytale mode, with some aspects of that far future. And once I started doing that, I started liking it. I wondered—a couple of times—I found myself thinking, as a kind of inspirational cue: what would it be like if Mervyn Peake had written future SF? What would the vibe be? … I never got up to the bar, let alone over it, but that became a good bar to shoot for. So a character like Ash emerges, completely from wondering what Peake would have written if he’d been writing SF.

Did you originally plan for it to be two separate futures?

Well, that’s actually a good—there’s definitely a story to that. I had Flynne going, but I didn’t know—I hadn’t committed to what the reality on the other side of the Milagros Coldiron supposed “game” was going to be. And at one point, early on, I thought that like, going to Atlanta for her might be strange enough.

But then we went to London for something gloriously non-business-related and we wound up spending the afternoon with Nick Harkaway and his lovely wife, and at some point during that afternoon, Nick started telling me in glorious, and possibly completely fictional detail—I’ve never had the heart to look it up—how the government of the city of London actually works, and how spookily non-democratic it manages in some ways to be, and how nobody ever really elects these people.

And it completely delighted me, and in the course of that conversation I decided that what was on the other side of the video game screen for Flynne was this relatively far-future London, run by those guys, which is really all I knew about it at that point. So when I came back I put that plan into action and it instantly worked.

… It has a very, very long setup, in some ways, but I just hope people will enjoy that as much as I did. I didn’t want to hurry it. It seemed really important that the little chapters can zip right along, but I wanted the reveal, as they say in Hollywood, to be kind of more like a strolling pace, if that makes any sense.

That’s actually how experienced it; I’m chugging along and reading and thinking “what’s going on here”, and little clues start to accrete, and little details start to pile up, bits that don’t quite fit. I think the whole thing clicked for me where Netherton is talking to Burton on the phone and there’s a line about “seventy-some odd years past”, and it all came into focus.

Well good! That’s what I wanted. … Going ahead and doing it was that scary. The other thing I wanted to do and which I did do was, I wanted to play it by my own possibly kind of perverse strict rules of golf in future SF … none of those—you understand—no expository lumps. Or if there are expository lumps, they’re kind of perverse lumps because they explain things that the reader doesn’t actually need to know. For better or for worse, I stuck with that, because I love science fiction that does that. It’s absolutely my favorite thing. Alternate histories that do that just—I just love them more than anything. The Alteration by Kingsley Amis is such an incredibly beautiful version of that. And he embedded The Man in the High Castle and a bunch of Keith Roberts books—they’re alternate worlds, book versions exist of alternate history. I love that stuff.

I also couldn’t help thinking of Borges and “The Garden of Forking Paths”.

Yeah, well, that’s definitely back in there somewhere. I’m very up front about this in the acknowledgements and thanks, but it’s not in the proof copy: the concept of third-worlding the past, because the past you contact can’t become the past where you live, is from “Mozart in Mirrorshades” by Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner, which is my favorite cyberpunk SF story.

In their story, physical time travel is possible, so you can go there and you can extract all of their valuable resources and pay them in electric guitars or whatever. Beads, right? It’s a brilliant story of colonialization. That’s in the glorious cyberpunk tradition of appropriation. I appropriated that, but what I realized almost before I appropriated it is the difference since 1984 when they wrote it, is that you don’t need to go there physically at all. It’s like, you don’t need to go there physically to totally go there, and suddenly that’s the 21st century. And I thought, okay, fair cop, this is the 21st century version of their model, if you can do it all virtually, and by telepresence.

It’s funny you bring that up, because this seemed sort of like what cyberpunk might be if it was invented in the 21st century rather than 1984.

Well that’s good! That’s actually very—that’s encouraging. I like that. I’m too modest to say it myself!

I know a lot people are going to say that you’re coming back to writing science fiction after the Blue Ant books. Do you ever feel like you’ve left?

No, but it’s complicated, as the young people put it, because I’m not entirely sure that I’ve ever been writing science fiction. It sounds absurd or Margaret Atwood or something, but for me it’s because I’m absolutely a native of science fiction. It was my native literary culture when I was fourteen years old—you couldn’t have found a more perfect example of the boy in those days that the publishers assumed they were selling the stuff to. And I just absorbed so much of it, and with huge delight, and it really was life-changing in all sorts of—I think—mostly good ways, but by the time I was eighteen, I’d consigned it to the toy box, or so I thought. And I didn’t really come back to try and write it until I was in my mid-20s and I already had an undergraduate degree in comparative literary critical methodology, and I knew a fair bit about the modern novel.

My idea of what SF was and how it worked was different than what the people at the local SF con. And I had really—I could tell, actually to my considerable delight—I held what were absolutely heretical views of science fiction and I didn’t really find anyone else who held them until I met Sterling and Shiner and people like that, and we found we had quite a bit of common ground. So even though I’m like a native sci-fi boy, when I started to write it, I did so with a peculiar attitude, kind of almost described as a love-hate relationship with the genre. … It’s like I love the genre, but I hate the people who tell me what should and shouldn’t be in the genre—or at least I hate hearing it. I can like them okay if they don’t bring that up.

So when I did three books that are pretty straightforward imaginary future stuff in their way, they’re certainly not ironic in any sense. And then I did three books—the Bridge books—in which I secretly gave myself permission to know that the characters I was casting those books with were contemporaries of the day in which I was writing the books. It was kind of odd—I’ve only started admitting to it recently. Actually it took me a while to realize that was what was going on. But Rydell is not a future guy. Rydell was a guy from the day in which I wrote.

Early 90s?

Yeah, he’s an early 90s man, and those are all early 90s characters, and—I haven’t gone back to those books for a while, but I imagine when people read them now, they read more like alternate history than an imagined future.

I did re-read them recently, and that is actually kind of how they felt.

I’m good with that, actually, I’m quite happy with that. But when I got to the end of those I realized that I had this really nagging feeling that my yardstick for the weirdness of the present moment was too short. That the bandwidth of weirdness had been steadily increasing outside the window while I’d been writing those six books. And somehow I thought that if I kept going, creating imaginary futures, I could wind up adrift. … How I navigate in writing this sort of thing is by having some confidence in my sense of just how weird the world is right now, so that I can make these sort of delicate increases in the bandwidth of weirdness in the book. It’s like I can calibrate the cognitive dissonance the reader is going to experience.

And I felt like I was losing that, but I thought that the way to fix it might be to call myself on the claim I’d been making all through the 90s, which was that if I wrote a book that described the present fairly realistically, that a lot of people wouldn’t even recognize that it wasn’t science fiction, and it work. So Pattern Recognition began as an attempt to do that, and the project continued with the two subsequent books. When I got to the end of those, I felt like I had the yardstick; that my yardstick was the right width, and I could do that increased bandwidth thing.

The Peripheral felt like a natural next stage of evolution from Zero History, as far as the sorts of things you were writing about, as you say, the weirdness in which we currently live. I saw something from Charles Stross, that he wasn’t going to be writing another Halting State book because the real world had caught up with him too fast.

Yeah. Well, there’s a certain point at which I realized without having really planned on it that I had a scenario in which the people from the Bridge books were interfacing with the people from the Sprawl books, sort of, and that was a sort of cheerful moment, and I thought, oh, we can do that. And they don’t even necessarily get along.

I know you’ve said of Neuromancer that you felt it was optimistic in that it posited a world where we hadn’t blown each other up, and I know from Distrust That Particular Flavor that you’re not into the Wellsian “you fools, I was right” kind of pronouncement. So what would you say to someone who wondered if The Peripheral was sort of your après moi, le déluge?

I don’t know. In some weird way it’s like the book itself is the answer, or it refuses to answer. Some critics have taken me to task for what they see as my kind of goofily happy endings. I’ve always thought that whether or not it’s a happy ending is entirely a matter of when you roll the credits. But with this one, I think there may be readers who get to the end and they go, “oh, well, that’s okay, everything worked out for them!”

And you know, bless them, those readers are nice, and bless them, because there are going to be other readers who get to the end and go “whoa, that’s the creepiest thing I’ve ever read.” Because it’s like, “Hey, don’t worry, it’s gonna be fine! Look how it worked out for these guys!” [Laughs] But these guys had an immensely powerful—if possibly dangerously crazy—fairy godmother who altered their continuum, who has for some reason decided that she’s going to rake all of their chestnuts out of the fire, so that the world can’t go the horrible it way it went in hers. And whatever else is going to happen, that’s not going to happen for us, you know? We’re going to have to find another way. We’re not going to luck into Lowbeer.

The world’s biggest cheat code.

Yeah. Well, also, how it’s set up for Flynne at the end—gave me the creeps! Really, its potential for not being good is really, really high. She’s lovely, and the whole family may be nice, but I’m not really sure of that. I mean, she’s lovely, but what are they building there? It’s got all kind of weird third-world bad possibilities. … I wasn’t expecting that actually, and it completely weirded me out, and I still haven’t really gotten my head around it. But I think with this one, there won’t be any sequels.

Really?

Yeah, because it’s got multiverse DNA and when you start doing sequels with multiverse DNA it’s—you’re just tempting fate. Like if you tacked two or three mediocre efforts onto this, it would ruin it. At least, it would ruin it for me. I’d rather do something completely different again, which is actually harder, and scarier, but, you know, more satisfying. You know, you can hold me to it. I don’t have a great record for sticking with that.

I did wonder where you could go from there, because it seemed very self-contained. And I’m glad I’m not wrong, that I had a Hitchcock refrigerator moment of thinking, “these things are really disturbing; this is creepy!”

It really is. Even though they’ve got their nice house and she’s gonna have a baby and everything, it’s like—what if they—they must have assassinated the vice president! It’s all kind of like one of those neo-fascist fantasies where the lovable good hero winds up ruling the world. It’s a little too close to that for comfort, but consciously so, and I’m sure a lot of people will get that.

Karin Kross transcribed the interview above and made some minor edits for clarity (and to clean up some of her own verbal flailing). She lives and writes in Austin, TX and can be found elsewhere on Twitter and at hangingfire.net.