There is nothing so powerful as one’s imagination. We’re readers, we know that. We get it. And yet, sometimes imagination can be offset or complemented by something else. This is, after all, the age of multimedia.

With greed-fueled war on the horizon, and with Smaug, Chiefest and Greatest of Calamities and arguably literature’s most famous dragon, once again on the rampage in the first trailer for The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies, it’s time to talk about The Hobbits—their juxtaposed film and literary incarnations alike, and why together J.R.R. Tolkien’s and Peter Jackson’s respective legacies are like chocolate and peanut butter combined.

You could consider me a Jackson apologist of sorts. I will always love the books first, if it must be said, and I can nitpick with the rest of you about the changes large and small that the upstart Kiwi filmmaker exacted in his Hobbit prequel trilogy, just as I could for the full Rings trilogy. But I’d also like to make a case for him in light of the many and scathing criticisms I’ve heard about the newer films.

Now I, too, was wistful when I heard that Guillermo del Toro wasn’t going to direct as originally intended. But unlike many, I was actually quite thrilled when I heard The Hobbit would be three films, not two, and not just because I want maximum cinematic indulgence in Middle-earth (though that is true, too). I thoroughly enjoyed An Expected Journey even though it wasn’t as satisfying as The Lord of the Rings. I, too, cringed at some of the over-the-top moments in The Desolation of Smaug (I’m looking at you, “Barrels Out of Bond”). I will likely do so again in The Battle of Five Armies, but holy fell-cows am I still excited for it! In the end I think the world is better for Jackson’s meddling.

Like many hardcore readers (and writers) of fantasy, I grew up with a substantial amount of Middle-earth bric-a-brac in my headspace. From various places, too: The Disney and Rankin/Bass cartoons, the unfinished Bakshi tale, and finally the books themselves. The sheer popularity of J.R.R. Tolkien’s work, its unparalleled staying power, and its straight-up linguistic beauty compels me to say that The Lord of the Rings is the finest slice of fantasy literature ever bound. There, I said it. If one could ever objectively say that something else has surpassed it, it would be nigh impossible to convince me because you can’t really compete with nostalgia. Mine or anyone’s. And it’s downright difficult to compete with the writing itself anyway.

If the Tolkien Estate one day stumbled onto an old trunk with an envelope in it upon which old J.R.R. had scribbled “a couple more songs I meant to add to the ‘Tom Bombadil’ chapter” and then decided to insert said lyrics into the trilogy after the fact, I’d be into that. Tolkien’s ghost could show up and add whole pages of additional travel description of Frodo’s and Sam’s journey through the Dead Marshes or the Three Hunters’ trek across Rohan—you know, all those walky bits that impatient modern readers like to groan about—and I’d eat it up. His narrative is that good.

But here’s the thing: I love the books twice as much now because Peter Jackson’s films happened. Seeing another’s thorough vision—and let’s be clear, it’s not Jackson’s alone, there were thousands of people involved in the making—makes me appreciate the depths of old John Ronald Reuel’s work. When you discover someone likes the same thing you like, it’s exciting, isn’t it? This is like that, but tenfold.

So why is this a big deal? Because what if it didn’t happen? The books would endure quite well, of course, but far fewer people would know about them. Likewise, many of the nuances in Tolkien’s epic would remain just that—discussed, maybe, in some classrooms, book clubs, or scattered conversations. But now? Millions more who would never have encountered the books will benefit from that Oxford don’s sagacious words. Or better still, seek its source! One specific line often comes to mind. In Chapter 2 of The Fellowship of the Ring, after Gandalf relates the story of the One Ring to Frodo, he says, “All we have to decide is what to do with the time that is given us.”

It’s a single statement, a diamond in a rough of diamonds, but I’ve overlooked it before. In the film version, Gandalf rephrases the same line specifically for Frodo in the dark halls of Moria, and it is echoed again later in the final scene. The significance of one’s own choice is woven into the movie’s central theme in a way that makes the wisdom resonate all the clearer. And so the line—universal truth that it is—has become more memorable. Plucked from the book like a pull quote and given greater emphasis in a shorter medium.

Have you ever heard someone read aloud a story you already knew and had it come alive? Someone else’s accent or inflections, or the simple emphasis they place on already familiar words changes it, makes it more than it was. Because here is another person with a different point of view appreciating it in their own way. Sometimes things change in the telling.

Take the famous Venus de Milo sculpture. Admired for her beauty—and the mystery of her missing arms—she’s already a beloved icon of ancient Greece. Now suppose someone finally unearths her limbs, partially intact, along with clues as to how she’d lost them. With this new evidence, there’s talk of a theft, a betrayal, a voyage, and a storm. Intriguing! The Venus de Milo just got more interesting! Now she can be considered in a new light. Or not; that’s up to the beholder. Art enthusiasts can keep on admiring her just as she was in all her elegance and ancient allure, while fans of mystery chase the clues and form little clubs to talk about it. And some of the latter go on to become legitimate art enthusiasts who enjoy both the original and the “retelling.” Win-win!

Yes, I just compared Tolkien’s and Jackson’s works to a dismembered, half-naked statue. A little weird, but here we are.

When the first Fellowship of the Ring teaser aired almost a year before the movie itself, I pulled an unplanned all-nighter. After watching it repeatedly, I could do nothing but privately geek out and lie awake, thinking about this literary epic I loved so much and wondering how on earth it could all be contained in even three movies (even all the extended versions linked together make for a seriously abridged version of the story).

Peter Jackson’s films have been ingrained in pop culture long enough now that we can easily take them—and all they’ve paved the way for—for granted. No way would HBO have been able to offer its enduring and bloody vision of Westeros without Jackson’s bold move. His success made the otherwise niche film genre of fantasy perceived as financially viable. Before Jackson, there were some excellent fantasy films—The Neverending Story, Willow, Ladyhawke, Labyrinth, The Princess Bride—but none quite hit the mainstream nor loosened the purse strings of movie studios like his.

Except for the angriest of Tolkien purists, I don’t think too many people would disagree that Jackson’s first trilogy was largely excellent. Not as many, however, are won over by The Hobbit prequels. Though still profitable for their makers, these movies haven’t had as staggering a box office impact as their Rings counterparts. And I am quick to admit, while much of the charm has returned to the cinematic Middle-earth and the casting is solid, they’re also not as meritorious. Where the changes Jackson made to Rings have elicited plenty of reader complaints, his Hobbit changes are far more extraneous. At times, they feel more like fan fiction than mere fleshing out.

And yet I can understand why such changes are made, in ways that book fans don’t wish to acknowledge. In his excellent talk “Tolkien Book to Jackson Script,” Tom Shippey, Tolkien scholar and literary consultant to Peter Jackson, tells us that the target audience for The Lord of the Rings was teenagers. Had been from the start. Hence Legolas skating on a shield down a flight of steps at Helm’s Deep. It’s one of those moments when adults shake their heads or roll their eyes but it’s also one of those moments which allowed the movies to happen in the first place. Is compromise a realistic part of life? Yes. Could New Line Cinema produce fantasy films at no cost? No. Tolkien wrote his books for fun with no promise of great wealth, but for Jackson and a host of film industry folks it was a job—albeit a labor of love—with money backing it and exceedingly high expectations all around.

I could happily discuss the pros and cons of each and every change made from book to film, especially in An Unexpected Journey and The Desolation of Smaug since they’re more recent. But there are really two points I wish to make.

First, about that target audience, it’s more inclusive than people think. One of the outcries among film naysayers concerns its violence, action, and sheer ferocity against the assumption that Tolkien originally intended The Hobbit as a simple children’s book. Aren’t the films betraying the simplicity and fairy tale nature of the story as written? Well, maybe, but deliberately. The fantasy world itself as viewed peripherally in The Hobbit is a nascent Middle-earth, not fully formed by a long shot because Tolkien himself hadn’t yet envisioned the larger setting. Not until he was asked by his publisher—much to his surprise—to come up with more stories about hobbits. When he finally got around to it, Middle-earth was becoming a different and many-layered place.

We can agree that The Lord of the Rings most certainly wasn’t for children. It was a more expansive, mature, and logical realm that Tolkien developed to house both his bucolic hobbits and evil immortal spirits bent on enslaving the world. When Tolkien name-dropped the Necromancer in The Hobbit, he did not then know of Sauron. When he wrote of the fallen Maia named Sauron years later, he most certainly assigned the Necromancer to him. The Mirkwood “attercops” were just giant spiders, but when Shelob was invented, it is suggested they were of her brood. The Lord of the Rings looks back, but The Hobbit does not look forward.

Jackson’s films look both ways for greater continuity. His first trilogy was the financially successful model the Hobbit prequels would follow; it only makes sense that they would cater to Rings moviegoers (teenagers + everyone else who happened to enjoy them), not newcomers to The Hobbit. It shows in the many—and I would suggest too many and too obvious—parallels that the films make. Gandalf’s incarceration in Dol Goldur, the summoning of Eagles via moth, the return of the Nazgûl, and so on.

Then there’s the fact that Tolkien himself didn’t truly consider The Hobbit a children’s book or least regretted the association, even the “talking down to children” style of his own narration in the early chapters of the book. That narrative evolves so that by “The Clouds Burst” (the chapter with the Battle of the Five Armies), it’s a different sort of voice altogether with a more serious tone. Referring to his own kids, Tolkien wrote:

Anything that was in any way marked out in The Hobbit as for children, instead of just for people, they disliked—instinctively. I did, too, now that I think about it.

Although kids love it and many of us count it among our childhood favorites, The Hobbit was never especially kid-friendly straight through. Literary critic and poet Seth Abramson explained one such point quite well in an interview for The Philadelphia Review of Books:

Imagine a child, or even a pre-teen, in the 1930s or any decade, being confronted with (and confounded by) the following words or coinages (among others) in just the first chapter of a so-called “children’s book”: depredations, flummoxed, larder, porter, abreast, fender (the indoors kind), hearth, laburnums, tassel, confusticate, bebother, viol, audacious, conspirator, estimable, remuneration, obstinately, reverence, discretion, “market value.” (Not to mention words far more familiar to children now than would have been the case in the 1930s, given our national obsession with the Tolkienesque: for instance, runes, parchment, wards, expeditions, sorcery, and many others.)

The second point I wish to make is about what Jackson’s newest trilogy is actually portraying versus what people assume it is portraying by its title.

Here is the crux: Jackson’s three Hobbit films are not merely an overblown adaptation of the singular book. Rather, they are an adaptation of seminal events that transpired in Middle-earth prior to the War of the Ring, and these events do notably contain the full adventures of Bilbo Baggins as depicted in The Hobbit. Yes, it is misleading that they’re using that title—money, branding, and name recognition at work—but the movies represent a great deal more. We know from various appendices that other events were transpiring but were not explored in Tolkien’s original book, were not part of Bilbo’s experience. Because, again, Tolkien hadn’t gone that far at the time. It was only retroactively that he connected the dots while writing The Lord of the Rings.

In the book, the dwarves are captured by “the Elvenking.” Only in the Rings trilogy does Tolkien name him Thranduil and establish Legolas as his messenger and son. I hope book purists wouldn’t rather he have stayed “the Elvenking” and named no others among the Wood-elves. I find both Legolas and Tauriel to be acceptable additions to the story, though the prominence of their roles is debatable. And as for Tauriel herself, as most know, no such character existed in the books. But female Elves exist, it’s more than all right to show them as more than blurry extras in the background. Now, suggesting a brief, ill-fated romantic connection between an Elf and a dwarf….yes, that’s a little bit of Jackson fanfic added for specific storytelling reasons that many of us shrug at. I’m guessing it’s in part to heighten Legolas’s grudge against dwarves. Unnecessary, but whatever.

Several other elements in the films did feel stretched or fabricated at first, but were in fact referenced in the books and, I think, were rightly expanded. One such connector to The Lord of the Rings is the idea that Sauron would have utilized Smaug “to terrible effect” in the War of the Ring had Gandalf not helped orchestrate the dragon’s downfall. This is straight out of the “Durin’s Folk” section of Appendix A in The Lord of the Rings. Meanwhile, from Appendix B we know that shortly after Gollum was released from Mordor, Sauron’s forces attack Thranduil’s realm and that the invasion was long and hard-won. How differently might have the Wood-elves faired if Sauron had a dragon at his disposal?

Likewise, when Gandalf parted company with Bilbo and the dwarves in The Hobbit, he went to “a great council of the white wizards” (later identified as the White Council) and that they “had at last driven the Necromancer from his dark hold in the south of Mirkwood” (i.e. Dol Goldur). Of course, in the book, Gandalf had known for years that the Necromancer was the very enemy he was sent to Middle-earth specifically to oppose. Jackson altered the timeline and made this revelation part of The Desolation of Smaug’s narrative—a stronger plot point for non-reading moviegoers, perhaps, but iffy for us book fans who wish he didn’t meddle this much. Then there’s Radagast, who was considered part of the White Council in Tolkien’s story later, was in fact mentioned in The Hobbit both as a wizard and “cousin” of Gandalf’s.

Finally, the orc Bolg is referenced five times in The Hobbit, and he is the only named villain in the Battle of the Five Armies, so I find it proper that he is given greater screen time in the films. Strangely, we meet him only after we meet his father, Azog the Defiler, who in the books was slain long before. While Bolg and Azog did not track Thorin as they do in the films, there is an implied grudge between the orcs of Moria and Thorin’s people to make the conflict more personal.

Lest anyone think that I fully embrace the Hobbit films just as they are, I will say that my chief complaint is the constant upstaging of Bilbo. Martin Freeman as the “burglar” Baggins is absolutely perfect, but some of his potential has been overshadowed. Bilbo’s moments of heroism are too few and far between in this retelling, in both Mirkwood and the Lonely Mountain. I always felt that even though Jackson’s version of the Rings trilogy was truncated (understandably) and sometimes sadly reworked (Faramir especially), he absolutely captured the spirit of Tolkien’s work. Yet I feel that in showing off with his CGI sequences and the increased prowess of secondary characters, he’s demoted Bilbo to a tag-along, sometimes hero instead of the repeated savior of Thorin’s quest and by extension, the fate of Middle-earth.

On the flipside, the dwarves in Tolkien’s book are given very little personality beyond the color of their hoods and the state of their beards. Thorin is characterized the most, and we get some vague impressions of a few others like Balin (he’s the eldest and most reliable) and Bombur (he’s fat). Beyond that, sadly, even Walt Disney’s dwarfs have more distinction. But An Unexpected Journey alone seemed to introduce me for the first time to the characters of Bofur (he’s the blue-collar everydwarf you could have a malt beer with) and Dori (he’s refined, polite, and likes chamomile). And holy Durin’s Day, Jackson’s version of Balin is the best!

This first look at The Battle of the Five Armies is gripping. Perhaps Peter Jackson, Fran Walsh, and Philippa Boyens will make up for some of the rushing-through-the-good-parts (alas, Mirkwood and the spiders should have been a longer and more terrifying ordeal), their plot-stretching (Tauriel and Kili), and history-rearranging (so did Gandalf not acquire the map and key to the Lonely Mountain in the dungeons of Dol Guldur from Thorin’s dying, deranged father?). I have been promised some goblin-hewing action at the claws of Beorn-in-bear-form. And I’m particularly keen on seeing the White Council push out from their chairs, smooth out their robes, and forcibly evict Dol Guldur’s worst squatter ever. Galadriel, in battle? Yes, please.

Will it be like The Hobbit as I envisioned it when I read it the first few times? I daresay it better not, nor anyone else’s. Nostalgia is powerful but I want to see other visions of this beloved classic. Peter Jackson may not be the final word on Tolkien, but he needs to finish what he started, to bring us “there and back again.” Let’s let him with open minds.

Lucky me, I’m still holding onto a bit of that wonder from that surreal first Fellowship trailer of long ago. I still sometimes marvel: OMG, do millions of people who barely knew the books existed actually know who Legolas is now? Or Samwise. Or Saruman-the-freaking-White?! Is Sauron really a household name now? Yes, he is! I’m still reeling, because I remember a time when only fantasy readers or the fantasy-curious even knew the name Gandalf.

And now, because of Jackson’s films, more people have turned to the literature, grasped the enormity of what Tolkien had created, and then, like the dwarves of Moria, delved deeper. Newborn Tolkien fans can discover just what it means to be one of the Istari, know who Eru Ilúvatar is, and respect the Maiar.

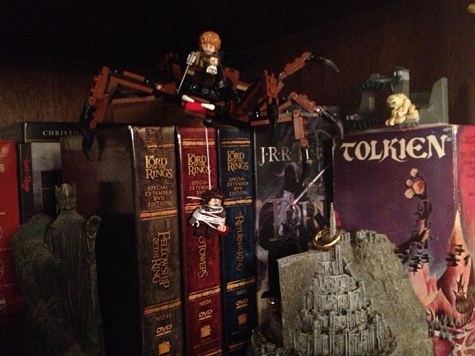

That’s right! With Tolkien’s story flowing fully into the mainstream, I can create something like this and more and more people will get it.

Thanks, Peter! (And the zillion other folks who brought it to greater life.)

Jeff LaSala gave his firstborn a Quenya middle name and isn’t sorry about it. He wrote the Silmarillion Primer, has too many Lord of the Rings toys, regularly plays Dungeons & Dragons, and frankly, refuses to grow up. He wrote a couple of SFF novels.