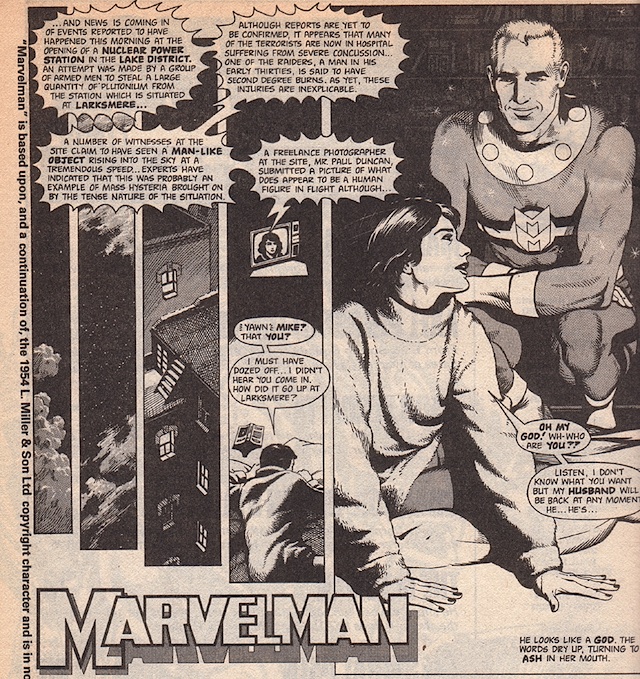

Before the comic book world had The Dark Knight and Watchmen, 1982 gave us a revolutionary, revamped Marvelman in the pages of Warrior #1—a character that a few years later achieved more fame and acclaim under his new name of Miracleman, courtesy of American publisher Eclipse Comics.

Before the rage of ultra-realism, sex, violence and rock ’n’ roll were in all mainstream superhero storytelling, writer Alan Moore and a group of committed artists did it first and better with Miracleman, a forerunner to the dramatic possibilities that an entire industry would attempt to force onto all their heroes. This uprising was the first time that an established superhero character was pushed to its fullest dramatic possibilities, and then some. Here was a costumed heroic comic character ready to give the entire world peace, a true utopia unlike any ever seen in the art form. Subsequently, a young Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham would pick up the torch and continue to beautifully explore the ramifications of said bliss.

Now that it appears Marvel Comics has settled the copyright nightmare that have kept these stories out-of-print for over a decade, a new generation is ready to discover perhaps the greatest superhero novella ever told.

The original Marvelman was a character invented not by divine inspiration, but by practical necessity. Back in the early 1950s, Len Miller and Son (an independent British publishing outfit in the ’50s and ’60s) produced all sorts of comics in a variety of genres, many of which were American reprints with some new filler content. The most popular of all Miller’s titles were the ones featuring the adventures of Captain Marvel, Captain Marvel Jr., Mary Marvel and The Marvel Family. All of this content and the characters therein were licensed from Fawcett Publications, U.S.A. But trouble was brewing back in the States; Fawcett was locked in a court battle with National Publications/ DC Comics, when the latter claimed copyright infringement in that Captain Marvel was too similar to their Superman property. By 1953, Fawcett agreed to terms retiring the entire Captain Marvel family, settling with DC Comics for $400,000.

Across the pond, Len Miller was perplexed with the scenario that the days of his most lucrative titles were seemingly coming to an end. In desperation, he made a phone call to Mick Anglo (an editorial packager of content for comics and magazines) for an answer to his dilemma.

All throughout the ’50s, Mick Anglo (born Michael Anglowitz) ran a small studio that gave employment to many hungry and lowly paid writers and artists (mostly ex-servicemen) in modest Gower Street, London. He was an independent operator who had provided cover art and content for Len Miller’s company, amongst other clients. Anglo’s solution to Miller’s problem was simply to not reinvent the wheel, but give the readers what they wanted under a different guise. As Anglo told me in 2001, “Yes, it was my creation except everything is based on somebody else: a bit of this and a bit of that. With Superman, he’s always wearing this fancy cloak with a big ’S’ on his chest, very intricate really. I thought that was too hard to emulate, so I tried to create something that was easy to draw and easy to market. I did away with the cloak so that I didn’t have to draw the cloak, which was awkward to draw, and played with a gravity belt, and they could do anything without all these little gimmicks.”

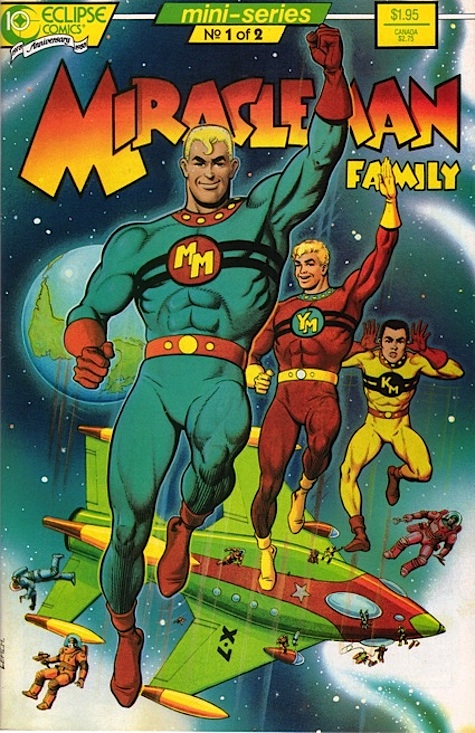

Without missing a beat (or a week), effective January 31st, 1954, the final British issues of Captain Marvel and Captain Marvel Jr., respectively, featured an editor’s letter announcing the retirement of the former heroes and the imminent arrival of the brand new Marvelman (a.k.a Mickey Moran) and Young Marvelman (a.k.a. Dicky Dauntless), in the very next issue—members of the Captain Marvel fan clubs were automatically rolled over to the brand new Marvelman fan clubs.

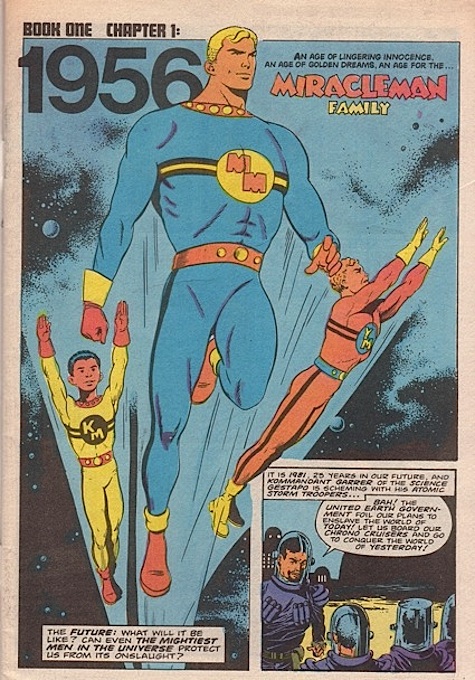

Let’s face it: Marvelman wasn’t at all unlike his predecessor. He was a young newsboy who could transform into an adult-sized superhero with a magic word; he was just as powerful as Captain Marvel; he basically had all his traits; he even had a new diminutive evil thorn named Gargunza, who could have easily been Dr. Sivana’s lost brother. Any differences were purely superficial. Unlike the darker features of Captains Marvel and Marvel Jr., the doppelganger and his junior counterpart were blond and blue-eyed. And instead of a Mary Marvel clone, a child hero named Kid Marvelman (a.k.a. Johnny Bates) was later introduced in the pages of Marvelman #102. Despite these minor changes, young British readers were apparently naïve enough to embrace the new characters, because Marvelman and his related titles would remain a constant for nine years!

The original Marvelman comics were produced hastily in a studio environment; the only goal was to get the books done rapidly and move on to the next paying assignment—most artists were paid only one pound for a full page of art. A lot of times the story, art and lettering suffered from the hectic time-crunch; many of the early Marvelman stories are fairly straightforward, derivative and workman-like in substance. The very best of the vintage Marvelman stories had a nice, whimsical feel that invited children to devour them; many of the finest tales were illustrated by an up-and-coming Don Lawrence (of Trigan Empire fame). With the rare exception of a few specials, these weekly British comics were black-and-white publications on very shabby paper that kids could buy for mere pennies, because essentially this work was strictly child’s fare material that never pretended to be high art or anything else.

What made Marvelman a remarkable phenomenon was the fact that he was England’s first truly successful superhero. Unlike us Americans (yesterday or today), post-World War II British comics readers have always enjoyed a bit more variety in their funny books. Basically, the superhero genre was left to America.

By 1960, Mick Anglo departed the title, the book’s sales were in a downfall, and there was no influx of new stories. Ultimately, Marvelman and Young Marvelman would uneventfully cease publication in 1963. It appeared that the characters would simply fade into obscurity… Then came the ’80s.

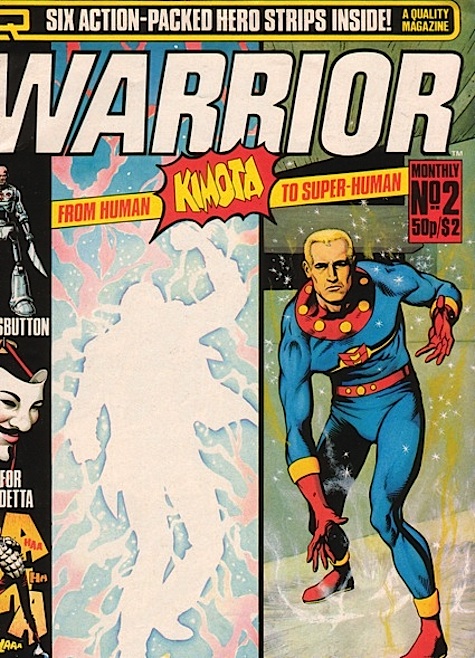

Back in 1981, fate played a major hand in the comeback of a dormant British comic book superhero character named Marvelman. Former Marvel UK editor Dez Skinn was tired of doing all the heavy editorial lifting for others when he decided to branch out and start a new company called Quality Communications. With his rolodex and publishing experience, he took a chance on himself and started Warrior, a comics anthology magazine that somewhat followed the content tempo of Marvel UK’s comic magazine format.

But, more importantly, Quality shared copyright ownership with its young pool of British creators. As Warrior was revving up, Skinn began to entertain the idea that it would be beneficial for the magazine to have a known character featured within. In his eyes, there was no better character than “the only British comic superhero,” rebuilt and modernized for an audience only vaguely familiar with the name from comics lore. The bigger question then became: Who would helm this revival?

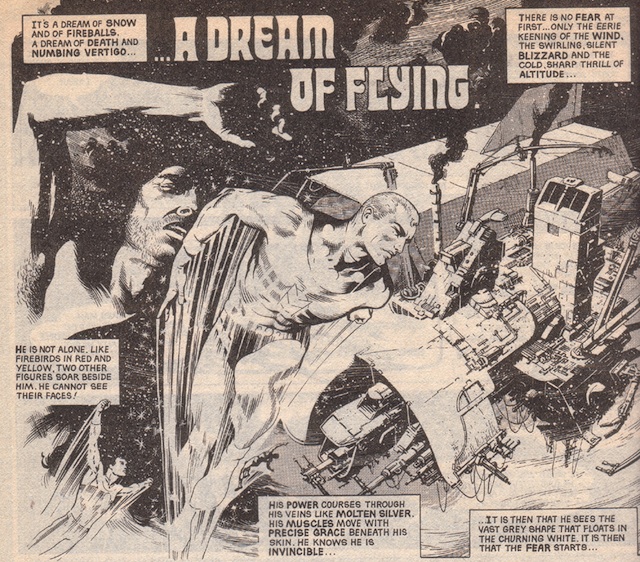

Around this time, an up and coming writer named Alan Moore was just beginning to make some waves on the UK comics scene with his short stories for 2000AD, the leading British comics anthology. But it was within their May 1981 newsletter that the Society of Strip Illustrators (a one-time organization for British comics creators) asked a group of writers about their comics goals and aspirations. Moore answered the questionnaire by expressing his wish for the maturation of comics storytelling, and with a call for more autonomy for its creators. But he cleverly closed his statement with the following thought, “My greatest personal hope is that someone will revive Marvelman and I’ll get to write it. KIMOTA!”

Whether it was via writer Steve Moore’s (a mutual acquaintance) recommendation, or Skinn reading that newsletter himself, Alan Moore was given the opportunity to pitch his spec for the character. Upon reading the story, Skinn was so impressed with the excellent substance, style and voice of that script that he knew immediately he had found his Marvelman writer. Moore’s vision was to modernize the character and ground him dramatically in reality. This would be his first long-form comics opus, a revisionist superheroic take that was bold and experimental.

About the genesis for his take on Marvelman, Moore explained to me that what sparked his treatment was the classic Mad strip titled “Superduperman” (in issue #4), written by the legendary Harvey Kurtzman and illustrated by the incomparable Wally Wood. Moore said, “The way that Harvey Kurtzman used to make his superhero parodies so funny was to take a superhero and then apply sort of real world logic to a kind of inherently absurd superhero situation, and that was what made his stuff so funny. It struck me that if you just turn the dial to the same degree in the other direction by applying real life logic to a superhero, you could make something that was very funny, but you could also, with a turn of the screw, make something that was quite startling, sort of dramatic and powerful… I could see possibilities there that didn’t seem as if they had been explored with any of the other superheroes around at that time.”

Even in 1981, the question of who actually owned the rights to the original Marvelman was a bit of pickle. Len Miller and Son (the original publisher of the Marvelman empire and apparent copyright holder) was no more. Publisher Dez Skinn got in touch with Marvelman creator Mick Anglo about his intentions to revive the character—because he intended to make the original 1950s material cannon to the revival, and even reprint some of the old Anglo Studio output. Anglo remembered, “He (Dez) contacted me and he wanted to revive it, and I said go ahead and do what you like as far as I was concerned.”

When Warrior made its debut in March of 1982, Marvelman’s return was just as an abstruse figure on the cover. Alongside Moore and David Lloyd’s “V For Vendetta” (another strip in the anthology), the readers responded enthusiastically to the realistic Marvelman revision and the artistic tour de force of Garry Leach, who redesigned the character and illustrated the initial chapters—subsequent stories would be illustrated by the talents of Alan Davis and John Ridgway. The superhero quickly became the magazine’s anchor. But the output of Marvelman stories ceased with issue #21, after a falling out between Moore and artist Alan Davis—the story came to a sudden halt midway into the second storyline, now known as “The Red King Syndrome.” For Alan Moore, his work for Warrior cemented his career and led to DC Comics offering him the keys to Swamp Thing, and the rest, as they say, is history.

Warrior, in the meantime, despite winning critical and fan acclaim—and despite the camaraderie and independent spirit amongst the book’s creators—came to an end. After twenty-six issues, the magazine could financially endure no more. Sales had never been such to make it a viable force, and despite being shareholders of the rights to their stories, the creators of these works could not survive on the low page rates that the magazine offered, said to be significantly lower than its competitors.

Another tougher obstacle that Warrior faced was an intimidating “cease and desist” letter from a British law firm on behalf of their client, Marvel Comics. Basically, Marvel felt that the name “Marvelman” infringed on their company’s trademark—never mind the fact that Marvelman first bore the name back in the Fifties, when Marvel Comics was called Atlas Comics. This last bit of revisionist history served to only thicken the plot for Marvelman’s fate in the UK. Luckily, Dez Skinn was already hard at work on bringing Marvelman and other Warrior strips to America, the land where everyone gets a second chance!

George Khoury is the author of Kimota!: The Miracleman Companion: The Definitive Edition.

The article originally appeared in two parts on Tor.com in July 2010.