Writers know that most stories can easily be split into one of two categories—“a child leaves home” or “a stranger comes to town.” The western is practically always the latter; someone enters a ramshackle settlement and changes how things are done, how frontier society functions.

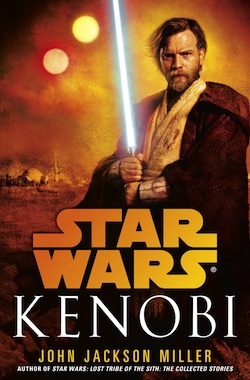

So what happens when a noble Jedi Knight finds himself amongst the moisture farmers, disgruntled Sand People and barren wastelands of Tatooine? If your thought was that it sounds just like a good old “enter the lawman” tale, you’d be right about that. John Jackson Miller’s Kenobi makes Tatooine stand in for the Wild West and sets up Ben (he’s not old enough to be Old Ben yet) as the only man capable of bringing justice to the frontier. Or something like that. Really, he just wants everyone to get along and forget he was ever there.

What’s great about the tale are the most important parts—Obi-Wan’s voice really shines through every time he’s on the page. Because Star Wars characters are so beloved, making sure that they sound like themselves is paramount, and “Ben” certainly does when he’s in the limelight. It’s particularly exciting because I think most of us can agree that Obi-Wan deserved a lot more than he got in the prequel trilogy, and getting some time with him to observe his immediate response to the events of Revenge of the Sith is both rewarding and heartbreaking.

The book contains his frequent meditations to Qui-Gon, and that’s equally heartbreaking; at this period in his life, Ben is so very alone that it makes sense for him to direct his meditations toward his old master. That he never receives an answer just hurts all the more. We see how his persona is perceived by the Tatooine population, how he takes steps toward those labels of “wizard,” “crazy old man,” and “hermit.” We find out why people know his name, and where his reputation comes from. It’s an important in-between story for those who wonder exactly how Obi-Wan occupied his time while keeping a watchful eye on Luke. There are more stories to be told, but this is where we find out how Obi-Wan dealt with his first days of exile, how he built a life on Tatooine after years of being used to the battlefield and acting as a Jedi.

In fact, the story goes to great lengths to show how being a Jedi makes it entirely impossible to live in the universe as a passive force: Obi-Wan constantly finds himself at the center of conflict no matter how hard he tries to hide. The fact that he manages to stay hidden enough to keep the Empire off his back until Luke grows up is a credit to his own abilities and a point against the Emperor’s hubris.

The secondary cast in the book are an interesting group of farmers, including a woman named Annileen, who really deserves better than she’s got. The camaraderie that she instantly forms with Ben (despite all his best efforts not to foster it) is probably the most interesting dynamic of the book, and though there is a romantic underpinning there, it bears out into a relationship built on mutual need and understanding. Which is great because Obi-Wan is always a more interesting guy when he is not acting opposite his superiors. Though Dexter Jettster and his Saturday Night Special Diner didn’t really make the point to us, we all know that Obi-Wan would be the best buddy to have around for gossip and a helping hand.

Star Wars novels in the past decade or so have made a point of fitting into subgenera outside of sci-fi and fantasy. There have been forays into horror and heists and thrillers, and so a trek into the western was only a matter of time. What this leads to is a pretty clear allocation of roles under the twins suns of Tatooine; the farmers are western settlers and the Tusken Raiders are obviously meant to be stand-ins for American Indians. Which makes sense logically, but does come off incredibly awkward in terms of ‘othering’ the Sand People. While the author makes every effort to show them as complex, feeling beings, and makes it clear how their actions are logical from their perspective, the Raiders spend part of the novel firmly under the “mysterious noble savages who believe in special sun gods” umbrella. The fact that they seem to internally refer to themselves as “Tuskens” (which is the settler name for them that they took on after a raid on Fort Tusken) only furthers that awkwardness; why don’t we know what they call themselves? Other similar details sprinkled throughout make the Sand People sections cringe-worthy, especially in the first half of the book before one the best twists is revealed.

It definitely doesn’t help that to start the central Tusken Raider of the story seems to think of Jedi as the “magical white man savior” deal we got from Dances With Wolves and Avatar. This is partly a result of the fact that the way of life for Sand People has changed drastically due to all the species that have come from off-world—humans aren’t entirely to blame in this case and Jedi are something of a novelty to everyone, after all.

The settlers themselves are predictably racist, which is certainly accurate to Tatooine and the Star Wars galaxy in general, and sheds a perturbing light on what Luke’s upbringing must have been like surrounded by similar folk. Every human settler on the desert planet seems to have low and nasty opinions about practically every other species. (And cultural misunderstandings abound as well; for example, we find out that the traditional Raider weapon is not actually a “gaffi stick”—the settlers just call it that due to mispronunciation.) There are community drunks and plenty of lowlifes to worry about, and no one is particularly happy. It is nice to get some background on the settlers themselves—why does anyone decide that moving to Tatooine is their best bet? How do families end up there and why do they stay?

It’s true that taking up other genres is a really fun idea for Star Wars novels, but the western genre is a fraught one. It’s probably best to leave it alone. Nevertheless, getting a chance to spend more time with Obi-Wan is one I’ll usually take up. It’s that wry sense of humor he’s got.

Emmet Asher-Perrin really just wishes Obi-Wan had a talk show where he made sarcastic comments at all his guests. She has written essays for Doctor Who and Race and Queers Dig Time Lords. You can bug her on Twitter and read more of her work here and elsewhere.