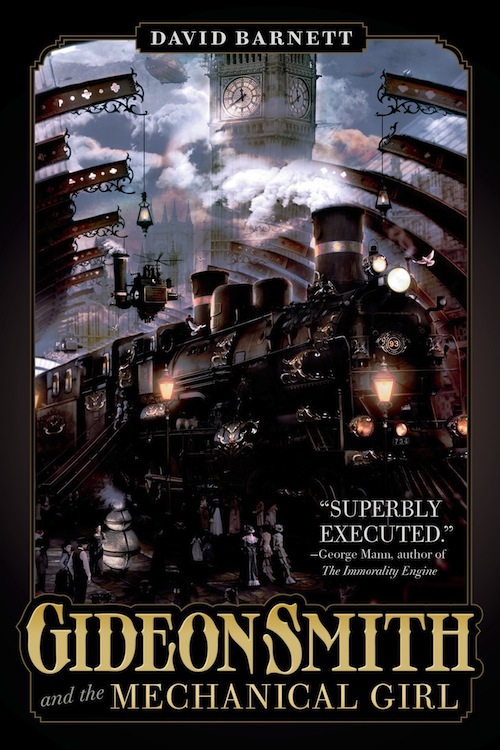

Check out David Barnett’s steampunk fable Gideon Smith and the Mechanical Girl, available September 10th!

Nineteenth century London is the center of a vast British Empire. Airships ply the skies and Queen Victoria presides over three-quarters of the known world—including the East Coast of America, following the failed revolution of 1775.

London might as well be a world away from Sandsend, a tiny village on the Yorkshire coast. Gideon Smith dreams of the adventure promised him by the lurid tales of Captain Lucian Trigger, the Hero of the Empire, told in Gideon’s favorite “penny dreadful.” When Gideon’s father is lost at sea in highly mysterious circumstances Gideon is convinced that supernatural forces are at work. Deciding only Captain Lucian Trigger himself can aid him, Gideon sets off for London. On the way he rescues the mysterious mechanical girl Maria from a tumbledown house of shadows and iniquities. Together they make for London, where Gideon finally meets Captain Trigger…

Two Years Earlier

Annie Crook never read newspapers. If she had, she might have known what was coming.

But she never read newspapers. She passed soot-grimed boys on the streets, shrill voices jostling to present the wares of the Argus, London News, Gazette, and a dozen others. France and Spain at each others’ throats. Skirmishes along the MasonDixon Wall. A dirigible crash in Birmingham. All a fog of hollered headlines to her. Annie Crook never read newspapers, because she was in love.

Not that it mattered whether she read the papers or not, because there were plenty of customers who came into the shop where she worked, eager to offer their opinions on the day’s events. Queen Victoria should take hold of the European problem and impose her will on France and Spain, they said, perhaps utilizing the German armies under her command. The Texan rebels in the southern regions of America should be thoroughly bombed out of existence by airships from the British enclaves in Boston and New York, they decided, as punishment for seceding from the Crown. The dirigible crash in Birmingham… well, that wasn’t anyone’s fault. At least it hadn’t been London.

Annie paused on Cleveland Street, where she had rooms. It was mid-June and quite a scorcher, though the sun had dipped over black-slate roofs. The flare of gaslight at Sickert’s window meant he was working. But it would not be Annie who posed for him tonight, glad as she was of the extra shillings. Tonight was for Annie and her man.

Cleveland Street was not far from the towering gothic spires and massive ziggurats of central London, from the Lady of Liberty flood barrier on the Thames, and Highgate Aerodrome. It was just off the Tottenham Court Road, where costermongers plied their trade and where Annie worked in a small tobacconist shop. The street was the haunt of the streetwalkers and cutpurses who lurked between its tall tenements. Every other window held an impecunious artist raging against the ever-present smog or a grizzled writer churning out some romance for Grub Street. But it was Annie’s home, and she was blind to its faults, because she was in love.

In her tiny bedroom, she considered herself in the cracked mirror. Her Irish brogue and mass of jet-black curls suggested a more pastoral life for Annie, but she had always lived in London. She would like a bath before he came, but a quick wash would do, and she would change into the scandalously close-fitting Chinese silk dress he had gifted her at Christmas. He would have to take her as he found her. He always did. She wasn’t, she had to admit, what you might call a good Irish Catholic.

Annie had barely fastened the last hook on the dress and arranged her hair into a bun with black wisps trailing to frame her angular, pale face, when there was a rap at the door. A flush rose on her cheeks, and she could barely contain a girlish squeal as she threw open the door.

He smiled broadly beneath the black bowler and silk scarf he always wore around his face when he visited, whatever the weather.

“Darling Annie!” He took her in his arms and kissed her. Annie wanted to shout it from the rooftops. She had a sweetheart, and he was a toff to boot.

To be young and in love in London in spring was very heaven. Not quite the words he’d read to her as they lounged in Hyde Park that sweltering July day the previous year, taking refuge from the merciless sun in the shadow of the platform of the stilt-train that criss-crossed Westminster, but close enough. They’d watched the first pinkish stones of the Taj Mahal that had been shipped over from India being relaid in honor of Queen Victoria’s golden jubilee. He told her it had first been built as a declaration of love.

“Is there nothing Victoria can’t do?” Annie had sighed.

A rare cloud had passed his brow. “No,” he’d said thoughtfully. “Nothing.”

Annie had met Eddy in that spring of 1887, while modeling for old Walter Sickert. Any given day could find Sickert drinking in the gin houses with bright-eyed villains or lunching in gentlemen’s clubs. Some of his acquaintances looked hungrily at the girls who posed. Eddy was different. The first time Annie met him, she was sitting astride a felt ottoman, aping the act of riding horseback. Eddy, curled into an easy chair, smoking cheroots and drinking brandy, never took his eyes off her.

“Is it true, Sickert,” he’d drawled nonchalantly, “that there’s what they used to call a molly house on Cleveland Street where the earnest young men go for solace?”

“I wouldn’t know,” rumbled the painter. Annie snorted to herself; Sickert knew full well of the brothel down the road. “Perhaps you should ask Annie; she is of the common classes.”

Eddy smiled mischievously. “I doubt it, miss, looking at your angelic beauty.”

“I could take you to the molly house,” she’d said, surprising herself. “If that’s your thing.”

Eddy had chuckled. “A raven-tressed colleen, and saucy with it. What say we go for a more intimate soiree, dark-eyed Annie Crook?”

“Don’t be a fool,” Sickert had hissed, his teeth clamped around the shaft of a paintbrush. “She works in a tobacconist, and she’s no stranger to coining it on street corners, if rumor be true.”

Annie pursed her lips. “I am here, Mr. Sickert,” she said. “I’d thank you not to talk as though I were some stray dog off the street.”

Sickert shrugged; evidently that was as high as his opinion of Annie rose. But Eddy continued to stare, and when the session was done he insisted on taking her for a drink.

“I’ll have a drink off you,” she conceded. “But nothing else. Despite what Mr. Sickert thinks, I’m not that sort of girl. What did you say your name was?”

“Eddy,” he’d said. “Just Eddy.”

Over the next year he courted her properly and chivalrously, and if Annie had, in the past, lain with someone for a few shillings as rent day approached, she foreswore such behavior for Eddy. She was his and his alone. They lay in a tangle of bedsheets in the darkness, listening to each other’s gradually slowing breathing. Night had fallen, and Annie stepped naked from the bed to light the gas lamp on the wall.

Eddy whistled. “You’re a fine figure of a woman, dark-eyed Annie Crook.”

She smiled thinly as she got back into bed. “That’s what you called me the first night we met.”

“A lot has changed since then,” he said, rooting in his trousers for his cheroots.

“Yet so much remains the same,” she said thoughtfully. Annie always fell into a funk after they made love. “I know nothing about you, not even your full name. You could have a wife and children, for all I know.”

She thought he’d laugh, but he said softly, “I’ve not treated you well, have I, Annie?”

She took his thin face in her hands and kissed his lips. “You have your reasons, I’m sure. You’re my sweetheart, Eddy, but you’re a toff. It wouldn’t be right, me hanging on your arm in polite society.”

He enclosed her hands in his. “But that’s what I want!” he whispered fiercely. “They’ve finished the Taj Mahal. We should go and see it. Tomorrow.”

“And will you be wrapped in your scarf, like last time?” she asked. “Even though it was July?”

Eddy looked broodingly at his cheroot. “No,” he said with finality. “That’s over. I’ve decided. We should be together.”

Annie’s heart skipped, but she kept her voice steady. “And we should also take a dirigible to New York and walk in the Albert Gardens on Manhattan Island. There are many things we should do, Eddy.”

“The Albert Gardens aren’t all that,” he muttered.

She stared. “You’ve seen them?”

“Many times.” He took her hands in his. “It’s a big world out there, and my… and Queen Victoria has most of it in the palm of her hand.” His eyes shone. “We could go to New York, you know, see the vast gothic towers. We could take a dirigible ride over the vast, untamed land that stretches right over to the Pacific, and the Japanese territories, or see the Mason-Dixon Wall they built to keep the Texans out. We can do all this together, if…”

She raised an eyebrow. “If?”

He dug into his pocket again and withdrew a small, dark box. “Annie,” he said seriously. “Look at me.”

She did. Something in his eyes made her heart take flight and stampede in her chest. He said, “I love you, Annie Crook. I want you to be my wife.”

She opened her mouth, but he quieted her with a finger on her lips and pressed the box into her hands. Fingers trembling, she opened it, and gasped. It was a gold ring, set with a huge, intricately cut stone glowing redly in the dim lighting. “Eddy,” she whispered. “It’s beautiful.”

“A mere gewgaw from my family’s coffers. We have thousands like it. Not one of them holds a candle to you for beauty, Annie.”

She placed the ring on her finger. “Thousands?” she said as she admired it. She looked at him. “Who exactly is your family, Eddy?”

He took a long drag of his cheroot, and the door to Annie’s rooms crashed inward with a shriek of splintering wood.

There were six of them. Four were tall, stocky, with bowlers pulled over their eyes, wearing black leather gloves that screamed danger at Annie. Of the other two, one was a short, fat man carrying a leather doctor’s bag, and the last was tall and thin, dressed in dapper tails and carrying a cane. He had a topper on his greased gray hair, and a thick mustache dangled beneath his hawkish nose.

Annie screamed and pulled the sheet around her nakedness, while Eddy gawped at the intruders.

“Do quiet the woman down, sir,” said the tall man mildly. It took Annie a moment to realize he was talking to Eddy.

“Walsingham! What is the meaning of this?” demanded Eddy, shuffling into his trousers. “What are you doing here with those… those gorillas? And Gull! You bloody bone saw!”

“I’m afraid this has gone quite far enough,” said the man whom Eddy had called Walsingham. “It would be best if you came with us now, sir.”

“I won’t!” said Eddy stoutly. “You have no right!”

At last, Annie found her voice. “Eddy, who are they? Do you owe them money?”

Walsingham laughed. “My dear…” He paused, frowning. “Do you not know?”

Annie felt her cheeks burn. “It’s Eddy,” she said quietly. “We are to be married.”

The short man, Gull, barked a laugh, then stared at her. He said, “I don’t think she does.”

“It’s true!” said Eddy, standing. “Annie Crook is to be my wife.”

Walsingham shook his head sadly. “I think not, sir. Gentlemen.”

Two of the bull-necked men shouldered their way into the room, and in a swift movement clambered over Annie’s screaming form and took each of Eddy’s arms. The one called Gull laid down his bag and took from it a dark bottle and a handkerchief.

“This is an outrage!” cried Eddy. “When Grandmama finds out…”

Gull tipped liquid from the bottle into the handkerchief and clamped it over Eddy’s surprised face. In seconds, he slumped, and the men began to drag him to the parlor.

Walsingham lit a cigarette and looked pityingly at Annie, cowering in the bed.

“I am truly sorry for the trouble you have been put to,” he said almost tenderly. “Things should not have gotten this far.”

“Where are you taking Eddy?” she wailed.

He exhaled a plume of blue smoke. “Do you not know who he is, really? Do you not read the newspapers?”

Annie shook her head. Walsingham told her. Annie’s eyes widened and her jaw dropped. She was about to tell him she was not falling for his sick joke, when she noticed Gull withdrawing a brace of cruel-looking metal instruments from his bag.

“What are those?” she asked in horror. “What are you going to do to him?”

Walsingham looked down at Gull, who waited by the bed. “He will spend some time in a private sanatorium, perhaps in Switzerland. He will recover. He will get over you. We have a match planned for him with a German girl.” He stepped forward and took a lock of Annie’s hair in his thin fingers. “Not a patch on you in the beauty stakes, but more his social equal.”

“Then… ,” said Annie, unable to tear her eyes away from the devices in Gull’s hands.

“Those are for you,” said Walsingham, as the other two men entered the room and roughly took hold of Annie’s shoulders. “We can’t have you running around London talking about this. It shouldn’t hurt.…”

“Much,” said Gull, grinning.

Walsingham waved his cigarette. “Much,” he agreed. Then he took his leave as Annie began to scream, “Eddy! Eddy! Save me!”

1

The Smiths of Sandsend

The night before, Gideon Smith had dreamed a dragon ate the sun. But there was no dragon in the blue sky, only a gull hovering on the hot air rising from the dry sand, seemingly screaming, save me, save me. And the sun had risen as usual, just ahead of Gideon, emerging from the iron-gray sea and traversing the cloudless blue until it began its descent toward the Yorkshire moors far from where he now stood. Save me, save me, cried the gull, its black face to the sea.

“And me,” whispered Gideon as he leaned on the tarnished railings, watching the men drag the day’s meager catch from their trawlers moored alongside the ancient wooden jetty to the tarpaulins laid out on the fine golden sand. Gideon’s day had been as unremarkable as the sun’s, and as he observed the men standing and shaking their heads at the small piles of haddock and cod glittering in the dying day, he idly prayed a dragon really would come and devour them all, if only to give them some respite from the unending boredom that was life in Sandsend. But the only things that came were the hovering gulls, their minds on eating only fish.

As the fishermen shooed the gulls away, one of the men detached himself from the muttering trawlermen and walked wearily up the beach to the stone jetty, as though the heavy oilskins and thick leather boots made each step a chore. He paused to light his pipe, then climbed the stone steps and rested his thick arms, clad in a cable-weave woolen sweater despite the summer heat, on the railing.

“How’s the leg?” he grunted, not turning his weathered face away from the knot of fishermen.

Gideon rubbed the thigh of his serge trousers. “Shooting pains when I woke this morning,” he said, the lie stabbing him sharper than his imaginary ailment. “It isn’t so bad now.”

Arthur Smith nodded and puffed on his pipe. “That’s why I didn’t wake you when we went out. Thought we’d give it another day. You’ll be fit for tomorrow?”

A week before, a hook had gashed Gideon’s leg while he’d been out on the trawler. There’d been a lot of blood from the fleshy part of his thigh, but it had looked worse than it felt. He looked at the paltry pile of fish, which the trawlermen were now loading up into barrows ready for delivery to Whitby to the south and the villages to the north and inland. He couldn’t with an honest heart delay any longer.

“Aye, Dad. I’ll be fit for tomorrow.”

Arthur Smith put out a hand as big as a spade to ruffle the black hair hanging over Gideon’s frayed collar in loose curls. “Good lad.”

Like a protective arm, the rocky promontory of Lythe Bank at the top of the village reached out to sea, as though pointing with silent accusation at the long, dark shapes of the factory farms on the distant horizon. The farms belched columns of black smoke into a deep blue sky broken only by the high, stately passage of a dirigible. Gideon had read in the Whitby Gazette there was talk in London of making a special dirigible with some kind of unheard-of engine, so they could plant the Union Flag on the very moon. He wished he could be on it when they built it.

“We should complain,” said Gideon, shaking the collar of his white cotton shirt to allow some of the sea breeze to circulate around his chest. “Write to our Member of Parliament.”

His father sighed heavily. “What’s the point?”

Gideon suddenly felt angry. “Look at that haul! It’s a tenth of what we were doing five years ago. The Newcastle & Gateshead shouldn’t be so far south, not at this time of year!”

His father shook his head sadly. “Remember the Wheeler?”

Everyone remembered the Wheeler. Three days before it sank with the loss of its fourteen crewmembers, its skipper had gotten an order from the assizes preventing the Newcastle & Gateshead factory fisheries from entering within a ten-mile boundary of Sandsend. Nobody could prove anything, but tough old trawlers like the Wheeler didn’t just sink without a little help.

“How old are you next birthday, Gideon? Twenty-four?” asked his father, spitting on the stone promenade.

Gideon nodded. His father said, “We’ve been trawlermen for four generations. When I was a lad, I thought we’d do four generations more. Five or six, even. I thought fishing was a job for life.… But now, I wonder, Gideon. When I’m gone…”

“Dad,” protested Gideon.

His father laid a hand on his arm. “When I’m gone… it’s no life for a young man, Gideon. Not anymore. I thought you’d be settled down by now, maybe have young’uns yourself, ready to take charge of the Cold Drake and let me retire. But the world’s changing quicker than I can keep up with it.” His eyes stared into the middle distance. “I’m just glad your mother’s not here to see the state we’re in.”

She had died fourteen years ago, in childbirth with his brother, who had lasted only a day. In another world, Gideon would have been the middle boy of a family of fishermen. But six years ago, his older brother Josiah had fallen victim to the influenza. Now there was just Gideon and his dad.

“What did you get up to today?” asked his father.

“I walked along the sand to Whitby,” said Gideon, glad to speak of other things. “Picked up some bread and vegetables from the market.”

His father gave a crooked smile. “And did you buy anything else?”

Gideon flushed, then nodded. “The latest issue of World Marvels & Wonders had just come in on the steam pantechnicon.… I had a penny spare.…”

His father laughed and ruffled Gideon’s hair again. “Why don’t you put us something on for supper, and maybe you can read me a couple of chapters before we turn in? The carriages are here for the catch.”

Three horse-drawn carts and one steam-truck, the latter in the black-and-white livery of the Magpie Café. How long before these faithful few finally succumbed to the cheaper supplies from the Newcastle & Gateshead was anyone’s guess, but for now there was work to be done. Gideon watched his father stride back down the beach, and he was just turning to go when he caught sight of a smaller figure, a little way along the shoreline, struggling to push a rowing boat three times longer than himself into the shallows. Gideon shielded his eyes against the sun. It looked like little Tommy, the son of Peek, who skippered the Blackbird. What was he up to?

Gideon walked along the sand and stood to watch the boy—only seven or so—loading a leather bag into the rowing boat. Gideon hailed him and waved.

“Where are you off to, Tommy?”

“America,” said the boy stoutly.

“Ah,” said Gideon, squatting down beside him. “Does your daddy know?”

“I’ll send him a letter when I get there,” said Tommy, heaving against the stern of the rowing boat. “Can you give me a hand with this?”

Gideon nodded, then scratched his chin. “Have you got enough for the journey, though? It’s an awfully long way to America.”

Tommy dug enthusiastically into his leather bag. “I have a loaf and a jar of pickle. Two apples.” He looked at Gideon. “Will that be enough?”

“I don’t know, Tommy. I’ve never been to America. Which part are you heading for?”

Tommy reached into the bag again and pulled out a magazine, then bit his lip. “Oh. This is yours.” It was an old edition of World Marvels & Wonders that Gideon had lent Tommy. The boy had a skill for drawing and liked to copy the illustrations of Captain Trigger’s adventures.

“That’s all right. It’s the one with the Bowie Steamcrawlers, isn’t it?”

Tommy nodded enthusiastically. “Captain Trigger teams up with Louis Cockayne, the American adventurer, and they defeat the Texan rebel Jim Bowie and his steam-powered armored desert-wagons. I thought I’d go there, see the MasonDixon Wall they built to keep the Texans from attacking the pioneering families.”

Tommy separated another sheet from the magazine, a map he’d clipped from an old book. “Do you know where that would be? It isn’t on this map.”

Gideon took it from him. “Let me see… here on the East Coast is British territory, Boston and New York. Over here on the West Coast, that’s ruled by the Japanese, or the son of the old emperor, at any rate. Nyu Edo.”

“That’s New Spain,” said Tommy, pointing to the south. “And Ciudad Cortes. I learned that at school.”

Gideon jabbed his finger in the middle of the map. “Then this must be where the adventure took place, north of the Texan strongholds, where they keep slaves and make them dig for coal.”

Tommy frowned. “Would they make me dig for coal?”

“Possibly. If they caught you. Might be best to go somewhere else first, maybe New York? They have tall buildings there called skyscrapers.”

“Taller than the ones in London?”

“So they say,” said Gideon.

Tommy put the map and magazine back into his bag. “I’ll go to New York, then.”

Gideon stood up, then put a hand on Tommy’s shoulder. “One more thing,” he said, pointing out to sea. “That’s east. America is west. You need to be on the other side of the country if you’re going to sail there.”

Tommy’s shoulder slumped under his hand. “Really?”

Gideon nodded. “Sorry.”

Tommy looked out to sea, then shrugged. “I don’t really like pickle, anyway. Maybe I should go home.”

Gideon nodded. “Me, too.”

“Is it cold for July, or is it these old bones?” asked Gideon’s father. Gideon grunted noncommittally as he cleared away the dishes from their supper and lit half a dozen candles and small oil burners.

Gideon retrieved the July 1890 issue of World Marvels & Wonders, its cover depicting a fearsome ape-beast menacing a lithe, heroic figure with brilliantined hair and an impeccable mustache, framed within a Union Flag border. He kept his penny dreadfuls stacked in piles in his bedroom, where he could, in summer, get the rays of the sinking sun to light his bedtime reading. World Marvels & Wonders was always his first choice, if only for the adventures of Captain Lucian Trigger.

This adventure was called The Man-Monsters of the FortyNinth Parallel, sandwiched between a lurid account of the latest victims of Jack the Ripper, who was slicing up streetwalkers in the capital, and a slew of advertisements for labor-saving kitchen devices and telescopes that could see the craters on the moon. Gideon read breathlessly aloud to his father in the flickering flames how Trigger had been dispatched by Queen Victoria herself to investigate reports of Frenchie bandits running amok on the border between Britain’s interests in the New World and Canada. His father’s eyelids began to droop after half an hour, so Gideon retired to bed to complete the story, reading with wide-eyed amazement how Captain Trigger had uncovered a conspiracy going back to Paris, but had been betrayed and abandoned in the frozen wastes. Near death, he had been discovered by a pack of grotesque, haircovered demihumans, known to the local Red Indian aboriginals as sasquatch. Despite their horrific appearance they had proved benign, and with their help Trigger foiled the French plot to assassinate the British Governor of Michigan.

It was a chilly tale for a summer edition but a thrilling one. And like all the Trigger stories, it was prefaced with: This adventure, as always, is utterly true, and faithfully retold by my good friend, Doctor John Reed, followed by the flourish of the good Captain’s signature.

One day he would leave Sandsend, Gideon promised himself for the hundred-thousandth time. One day he would seek adventure, just like Captain Trigger. Gideon Smith would be the Hero of the Empire, and he would meet his one true love, and he would truly live in a world of wonders and marvels. One day, but not today. Maybe tomorrow, thought Gideon, as he drifted into sleep.

Arthur Smith awoke before dawn from the disturbed sleep that sometimes troubles those who live their lives in tune with the sea. While not given over to whimsy as much as his son Gideon, Arthur had learned over the years not to ignore the insistent little voices speaking at the back of his mind. When he drew back the drapes in his bedroom and saw the thick sea mist rolling up the cliffs and making black islands of the ramshackle roofs of the fishermen’s cottages, he felt a slight shiver. He would have given anything to close the curtains and return to his bed, but there was a living to be made.

In the darkness, he creaked open the door to Gideon’s bedroom and for a long moment observed his son, snoring gently with the bedsheets wrapped around him, the pale square of a penny dreadful on the rug by his bed. Arthur felt a sudden wave of love for his only remaining flesh and blood. He’d told Gideon to be fit for work this morning, but his troubled sleep still bothered him, and he didn’t like that sea mist rolling in off the bay. Arthur fingered the polished piece of jet hanging around his neck on a leather thong. Gideon had found it on the beach fifteen or sixteen years ago and fashioned it into a good luck charm for his daddy. Arthur Smith never put out to sea without it, and he had a feeling he’d need it on this early morning more than any other. Let the boy sleep, he decided. Another day of dreaming wouldn’t kill anyone.

The Cold Drake, like all the Sandsend trawlers, was a gearship, built seventy-odd years previously on the Clyde. Arthur remembered the first time he had skippered her, taking her out beyond the bay just three hours after they had buried his father in St. Oswald’s churchyard on the top of windblown Lythe Bank. As his boots slapped along the wet stones, he could hear Milton’s heavy breathing as the old first mate cranked the paddle-gear, but couldn’t see him for the fog.

“Ho,” called Arthur.

“Skipper,” grunted Milton, his lined face framed by his oilskin hat emerging from the mist. “She’s cranked up and ready to go, the old girl.” He paused and chewed his ever-present tobacco. “We’re the only ones out, you know.”

Arthur grunted. “More for us, then, and more fool them. We got a full crew?”

“Aye.” Milton nodded, then squinted over Arthur’s shoulder. “Except… no Gideon?”

Arthur said nothing. Milton, like him, would have had that feeling in his bones that today was not going to be a good day. He muttered, “Shall we get moving? Those fish won’t catch themselves.”

The pace of a gearship was slow, and it was two hours before they reached the deep waters where they could drop the nets for cod. The sun was rising somewhere ahead of them, but the fog stubbornly refused to lift, so they were little better off. Arthur applied the shaft-brake, and the Cold Drake drifted in a silence that unnerved him. There weren’t even any gulls crying overhead.

The nets down, Arthur settled into the wooden chair he kept on deck and lit his pipe. The sea was millpond calm, and all there was to do was wait for the cod to flock into their nets. He puffed on his pipe and wondered what Gideon was doing.

At first, he thought the knocking was a gear slipping, or one of the springs wearing. He sat up in the chair, suddenly alert, and peered around. “Anybody else hear that?”

Arthur frowned. There it went again. He stood and walked to the port side. Probably a piece of driftwood or rubbish hauled over the side from one of the factory farms. He leaned over and looked at the black, oily water.

The first one came at him so quickly he didn’t have time to yell. He stepped backward in surprise, slipping on the damp deck. His first thought was that it was a seal, such as could be seen sporting out at sea on balmy days. Seals, though, rarely clambered up the side of a trawler, as far as he recalled. As the shape sat itself, hunched over, on the steel balustrade around the deck, he heard the other men find their voices, and he looked madly around to see panic on the deck. His hand went instinctively to the jet charm at his throat, and with his other he fumbled at his belt for his gutting knife, but it was too late. The Cold Drake was overwhelmed.

Gideon Smith and the Mechanical Girl © David Barnett