An invisible monster is what you can’t see coming. It has unknown qualities. With an invisible monster you don’t know when you’re in danger and when you’re safe —even if you retreat to your fortress you can’t be sure you haven’t locked the monster in with you. No one is an expert on the invisible monster, but everyone has the same relationship to it. It could just as well be peering over your shoulder as mine. We throw our spilt salt over our shoulders just in case it’s there.

But the things the invisible monster represents are things we don’t want to acknowledge. Like our fear. Like our paltry measures to make ourselves safe. That desire we have to make others responsible for any decisions that might lead to calamity. And there’s our suicidal aloofness, our soldiering-on. There’s our tribal love of holding our lives lightly in the eyes of others, all the “no worries” stuff. Nothing is any trouble. And we don’t have enough words for our troubles—all those nameless invisible monsters.

We’ve made our monsters invisible. Misery is always exceptional. No one ever feels like this, we think, since we never really hear about it. Or all we hear is the checklist that turns our sorrows into an illness. So we lose our job, and our income shrinks so much we have trouble putting petrol in the car. Then we can’t get out of bed, except to go to the doctor, check all the boxes, and take the pills (when we should take to the streets instead). Or else we don’t succumb to the siren song of symptoms. We don’t go to the doctor. Even when we feel next-to-nothing. Even when all we feel is numbness, neuropathy, as if, as soon as we become this miserable we also become lepers—numb-fingered, clumsy-footed, frozen-faced, and alone. Invisible, and monstrous.

We don’t go to the doctor; we start writing a book, and that book is a cascade of darkness, and it’s too maddening to live with, so we start another book, and finish it, because although it has the same darkness, it also has a seed of light, a zone of clarity. And that is where the invisible monster is standing, untouched and observant. The invisible monster has been with us the whole time, and has grown to understand our troubles. There it is: still in the turbulence, silent in the noise, clear in the murk, bright in the blackness.

There are invisible monsters from my childhood I vividly remember. There are the Dufflepuds that come thumping and whispering after Lucy Penvensie in The Voyage of the Dawn Treader. My older sister Mary read the book to me, after having read it herself. She performed it, relishing the suspenseful episodes. I can still see the giant footprints appearing in the frost of the lawn of the magician’s house. (Just as I can see the print of this episode of Lewis’s book in Mortal Fire—a novel with an enchanted house, a self-enchanting magician, and an invisible monster.)

Another indelible invisible monster of my childhood is the “monster from the id” in Forbidden Planet, a film I saw when I was ten on a black and white TV. When I watched it again in order to write this I was thrilled by its modernist pastel green, and gold, and soft pink interiors, and art objects. And the floating ceiling and architraves of Doctor Morbius’s house. And the planet’s puce smoke-bushes and celadon skies.

When I saw the film as a kid I wasn’t noticing the decor. I was listening for the monster’s cues. It always arrived accompanied by a warbling heartbeat on the sound track (like a heartbeat heard by the brain without the aid of the ears). It came, caving in the ground, and bending the steps of the spaceship as it climbed inside. It could only ever be seen outlined in energy, caught in the explorer’s puny force field and the slow drip of post-production laser fire.

My dad loved science fiction—he had a huge library of purple and yellow-jacketed Gollancz hardbacks. He was a permissive parent, and would encourage us to watch any science fiction that came on TV. My younger sister and I were often left shaky, sleepless, and over-stimulated by the likes of Forbidden Planet’s monster.

Dad admired the film (though not nearly as much as he admired The Day the Earth Stood Still). He liked its positive, co-operative view of our human future. He liked the massive remnants of the advanced alien civilisation destroyed by its own aspirational overreach. What he didn’t like was the Freudian explanation of the destructive power of the human subconscious. Dad was an iconoclastic atheist, and he thought Freudian psychoanalysis was just another religion, where the work of God and the devil were conveniently split into a new trinity between the superego, ego, and id. (Dad was a former Catholic.)

So, when we were watching the film—Sara and I clutching pillows—we got the final third with Dad’s commentary. The plot was a copout, Dad said. No man would be so threatened by encroachments into his territory, and abandonment by his daughter, to create an invisible monster. I wasn’t buying that. I was pretty sure that the adults I knew—disorderly, dictatorial, flighty, depressed, court-holding, hung-over adults—would be entirely capable of unknowingly making monsters, if, like Doctor Morbius, they were backed up by Krell machines.

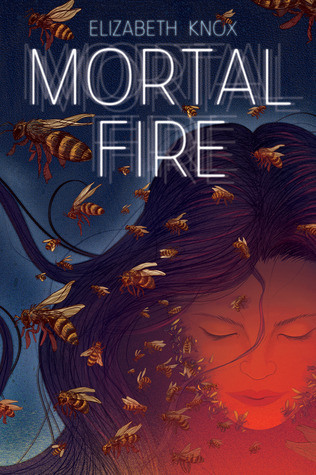

opens in a new window My two books this year— Mortal Fire and Wake— both have invisible monsters in them. Wake has an invisible monster that always returns, and won’t ever leave till there’s nothing left to spoil. Mortal Fire has a wild one, who learns, and adjusts its appetite, and is always there, holding everything in place—in thrall—till it has itself changed.

My two books this year— Mortal Fire and Wake— both have invisible monsters in them. Wake has an invisible monster that always returns, and won’t ever leave till there’s nothing left to spoil. Mortal Fire has a wild one, who learns, and adjusts its appetite, and is always there, holding everything in place—in thrall—till it has itself changed.

Do we change how we see the world when we suffer? Or does the world change? I think the world changes. Everyone who feels the green avalanche of their ancestors—of the dead—changes the balance of the self-consciousness of something, the something that knows when we know we’re launching ourselves out of the world with as little as possible still tangled with ourselves, bravely, mindfully, peacefully. Then we are doing something like what Canny does in Mortal Fire to the crumbling edge of the road in Lazuli Gorge—she knits it together. We go, and we push every particle of our lives back into the world of the living. It’s a kind of conservation. There is something rare we have, and we have to leave it behind us. We can’t put out in a boat we make ourselves. Any boat we make ourselves must stay on the shore.

Elizabeth Knox has been a full time writer since 1997. She has published ten novels, three autobiographical novellas, and a collection of essays. Her best known books are The Vintner’s Luck, and The Dreamhunter Duet (Dreamhunter and Dreamquake). Her eleventh novel, Mortal Fire, is available in June 2013.