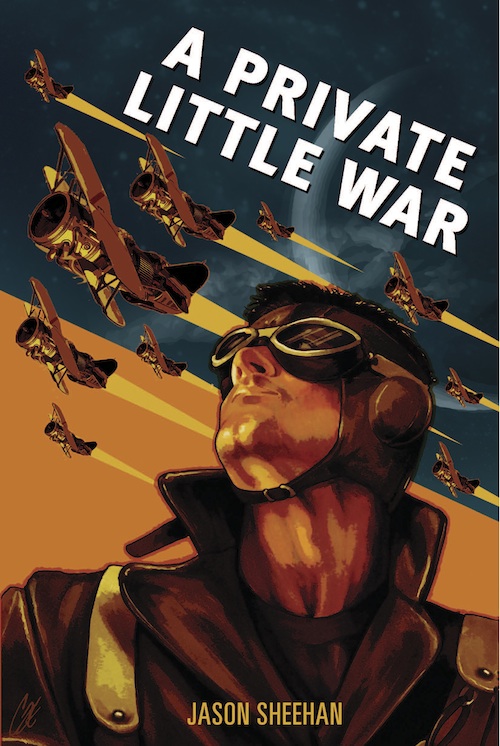

Check out Jason Sheehan’s A Private Little War, out on June 11 from 47North:

Private “security” firm Flyboy, Inc., landed on the alien planet of Iaxo with a mission: In one year, they must quash an insurrection; exploit the ancient enmities of an indigenous, tribal society; and kill the hell out of one group of natives to facilitate negotiations with the surviving group—all over 110 million acres of mixed terrain.

At first, the double-hush, back-burner project seemed to be going well. With all the advantages they had going for them—a ten-century technological lead on the locals, the logistical support of a shadowy and powerful private military company, and aid from similar outfits already on the ground—a quick combat victory seemed reasonable. An easy-in, easy-out mission that would make them very, very rich.

But the ancient tribal natives of Iaxo refuse to roll over and give up their planet. What was once a strategic coup has become a quagmire of cost over-runs and blown deadlines, leaving the pilots of Flyboy, Inc., on an embattled distant planet, waiting for support and a ride home that may never come….

One

It was a bad time. Everything was cold and sometimes everything was wet. When the wet and cold came together, everything would freeze and tent canvas would become like boards and breath would fog the air, laddering upward from mouths like curses given corporeal form. The ammunition, if not carefully kept, would green and foul and jam up the guns so that the men started stealing hammers from the machine shop, passing them around hand to hand until, one day, there were no more hammers in the machine shop and Ted had to order everyone to give them back.

“All of them,” he said. “Now.”

And so the men came up with the hammers—from their flight bags, from their pockets, or tucked beneath the seats of their machines. Every other man or so had stolen a hammer, and every other man or so gave his hammer back.

Kevin Carter did not give his hammer back. He stood with the other men as half slunk away to fetch back the hammers that they’d used to bang the shit out of their guns’ breeches when the shitty, greened ammo fouled their smooth operation. He stared after those who had to walk the flight line looking for their machines and watched those who rummaged through their kits for the tools, and when Ted looked him in the eyes, Kevin folded his arms across his chest and met Ted’s gaze with guiltless, frozen calm.

Of course he’d stolen a hammer. He’d been one of the first. But he’d be damned if he was going to give it back just because Ted had asked. Besides, it was in his machine in the longhouse and, at the moment, it’d seemed like a long way to walk.

Danny Diaz was dead. Mikke Solvay had drank himself useless and been sent home. Rog Gottlieb had gotten sick and was extracted in a coma that was next door to death. John Williams had been crippled with both legs shattered below the knee. None of the trip alarms worked. They were electronic—tiny little screamers, no bigger than a baby’s fist—and the cold and the wet fucked with their internal whatevers so that they failed as fast as they were deployed to the perimeters of the field. Also, they were all supposed to be connected together by lengths of hair-fine wire, but the indigs—the friendly indigs—knew about the wire and so stole every yard of it the minute it was laid. No one could figure what they did with it, but that didn’t stop them from stealing it. No one could figure what they did with dead batteries either, or buttons clipped off uniforms or shell casings, but they stole those, too.

The contact fuses in the bombs corroded. The cords that held the tents up would grow a white fur that looked like frost but wasn’t. Shortly after, they’d snap, and a tent would come down or sag like a drunk punched in the stomach and, for ten minutes or an hour, the men would all have something to laugh about. Especially if it happened in the middle of the night or in the rain. And even though no one was dying (or anyway, no one that mattered), it was a bad time for the war. Everyone thought so. And it made a lot of the men sick just thinking about it. They were fighting the weather as much as they were fighting the enemy and, slowly, they were losing. They all knew that something was going to have to change, and soon. There was just that kind of feeling in the air.

Two nights ago, the company had gotten word that Connelly’s 4th had moved into position across the river. They’d been turned back at the bridge, again near Riverbend, but had finally made their crossing at a heretofore undiscovered ford two miles downriver and were digging in by dawn. They were exhausted, but nearly at full strength due, in large part, to the overwhelming cowardice of Connelly himself. He was afraid of the dark, was the word. Doubly afraid of fighting in it. Triply afraid of dying in it. It was rumored that the downriver ford was found accidentally by some of his pikemen who’d stumbled onto it while retreating.

It was dark so, obviously, the company’s planes couldn’t fly.

The next night, Durba’s riflemen were put in place to secure the ford. On paper, they were the First Indigenous Rifle Company—the First IRC, attached as the fifth company, supernumerary to Connelly’s four-company native battalion of foot-sloggers and local militia—but called themselves just Durba’s Rifles or, sometimes, the Left Hand of God because Antoinne Durba (who’d claimed on many raving, red-faced occasions as a drunken guest at the Flyboy encampment, to once have been a missionary before finding another calling more suited to his disposition) was a man of vociferous, if rather selective, Christian faith. He seemed only to like those bits of scripture where God, in his infinite wisdom, was smiting something or someone, and had a disturbing tendency to insert his own name into these verses in place of the Almighty, referring to himself always in the third person—Durba smasheth this, Durba fucketh that all up and back again.

As a stand-in for the Lord Jesus was Durba’s only daughter, Marie, who’d once been his first sergeant and second-in-command. What made this proxy arrangement disconcerting (even more so than Durba’s own self-promotion within the spiritual hierarchy), was the fact that Marie had been killed more than six months ago—pierced through by a cavalryman’s lance on the Sispetain moors during a disastrous attempt by Connelly’s indigs to hold the last of the region’s high ground against an onslaught by overwhelming numbers of someone else’s. Marie’d been in the dirt now for some time, but that never stopped Durba from speaking of her as though she’d just gone ’round the other side of some tree for a piss. It got to a point where it began to bother some of the pilots and, one night, Carter asked him if he, Durba, still thought Marie sang the Lord’s praises so prettily with half a foot of native hardwood through her lungs.

“All souls live eternally in the light of God’s righteous fury,” said Durba.

“That count for the monkeys, too?” Carter asked.

“The natives here are abominations in his eyes,” said Durba. “Heathens who worship trees and clouds.”

“Well, if Marie loved Jesus and is dead and the monkeys pray to sticks and dirt but are still alive, whose fucking god does the math say is winning?”

At that point, the theological discussion devolved into punching, and the two of them had to be pulled apart and hustled out opposite doors. It was Fennimore Teague, Carter’s friend, who’d dragged him outside, shoved him backward, and held him off with one hand flat on Carter’s chest while Carter spit part of a broken tooth into the dirt.

“Baby, that was somewhat less than hospitable,” Fenn said, smiling while watching Carter close. “What do we say? No talking about politics, sex, or religion at the dinner table.”

Carter said that Durba had started it. That all he’d done was ask a question. That everyone was just as tired of hearing about Durba’s dead cunt of a daughter as he was and that no amount of talking was going to bring her back.

“Talking is what the man has left, Kev,” Fenn said. “To keep her close. Though I grant you, at this point, odds on her resurrection are running very long indeed.”

They laughed. What else was there to do? Everyone knew Durba was too sensitive. Eventually, Carter apologized and showed Durba the tooth he’d broken and showed him how he could spit whiskey through the hole like a sniper. The war went on and on.

Durba took position across the ford without firing a shot, though it was again rumored that Connelly, in a panic, had nearly ordered his 4th company to retreat once more when he’d heard the riflemen moving up in the night behind him.

The men—the pilots—laughed about this. “Connelly . . . ,” said Tommy Hill. “Fought every battle he ever saw walking backward.” They shook their heads, rattled their drinks, and said Connelly’s name over and over again the way one might speak of a younger brother or favorite pet, forever mixed up in something complicated beyond their years or wit.

“Connelly . . . Going to outlive us all.”

“Connelly . . . Fucking Connelly.”

“Connelly . . . ,” said Albert Wolfe. “That man is going to chickenshit himself right through this war. Afraid of the dark. Whoever heard of such a thing?”

Again, it was dark, so the planes couldn’t fly.

A Private Little War © Jason Sheehan 2013