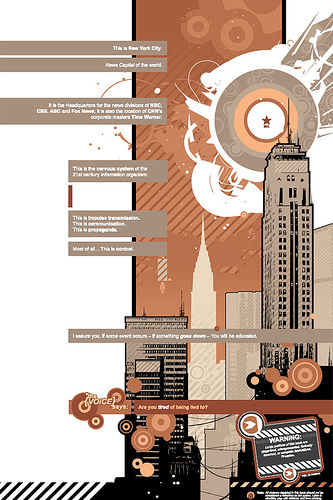

In the wake of the big “Marvel NOW!” relaunch, Marvel Comics’ resident mad genius Jonathan Hickman has taken over the reigns of Avengers—you remember, those guys from that movie?—and its sister (brother?) book, New Avengers. First exploding onto the comic book scene with The Nightly News in 2008 (which he both wrote and did the artwork for), Jonathan Hickman quickly established himself as a unique creative force, melding elements of infographics and epic poetry into his elaborate stories, with beautifully rendered charts and obsessively systematic plot complications. But there’s something about Hickman’s voice as a writer that stands out, an incredibly distinct pattern that I’ve noticed in his work that goes against many of the traditional rules of dramatic storytelling—or at least, the rules as I’ve learned them, according to Aristotle’s Poetics.

For those unfamiliar, Aristotle was a Greek philosopher, one of the leading minds on mathematics, physical science, ethics, biology, politics, and much, much more. Written around 385 BCE, his Poetics is generally considered to be the oldest extant piece of dramatic and literary theory. In it, he establishes a hierarchy of drama that has continued to serve as the basis of our entire concept of storytelling (at least in the Western world), by ranking the dramatic elements in order of importance:

- Plot

- Character

- Theme (or Thought)

- Diction (or Language)

- Music

- Spectacle

While this hierarchy was specifically created in reference to the Greek theatre of the time, it still holds true for most modern forms of dramatic storytelling (music, for example, is not particularly relevant for a graphic narrative). But in general, the works of Jonathan Hickman tend to focus primarily on Theme, Spectacle, and Plot, with Character and Diction bringing up the rear. That being said, this isn’t necessarily a bad thing; it’s in opposition to the standardly accepted rules of drama, but that doesn’t make it wrong (one could even argue that such innovation is necessary for progress in the modern age).

Consider Hickman’s first issue of Avengers (some spoilers here). The first four pages consist of a narration about creation and ideas, accompanied by beautiful images of exploding galaxies, transdimensional super beings, and marvelous technology courtesy of artist Jerome Opena:

There was nothing. Followed by everything. Swirling, burning specks of creation that circled life-giving suns. And then . . . [Insert Avengers logo] It was the spark that started the fire — a legend that grew in the telling. Some believe it began the moment Hyperion was rescued from a dying universe. Others said it was when The Guard were broken on the dead moon. Many more think it was when Ex Nihilo terraformed Mars, turning the red planet green. They were all wrong. As it happened before The Light. Before The War. And before The Fall. It started with two men. It started with an idea.

The language is vague, cryptic, and undeniably epic—but it doesn’t exactly reflect the content of the plot, or characters (and yes, it greatly foreshadows the issues yet to come, but still). As the story continues, we experience more philosophical discussions on similar themes about creation and ideas, first between Captain America and Iron Man, and then between our newly introduced antagonists. We’re quickly informed that there is a conflict, and the Avengers skyrocket to Mars while they catch us up to speed on this unseen conflict. There is a beautiful battle for several pages and the team is captured, leaving Captain America to return to Earth accompanied by more philosophical posturing in order to recruit a new team of Avengers.

This is the entire plot of the issue, and while such brevity is certainly welcome in today’s world of decompressed storytelling and reduced attention spans, it still takes a backseat to the larger themes and stunning visuals that carry the story. Hickman gets a few character moments in there as well, but that’s hardly his priority (although it is a testament to his ability as a writer that he’s able to communicate these characters to readers so swiftly). Captain America refuses to yield to the robot that beats him to a pulp, for example; Iron Man has lots of caffeine-inspired ideas. Thor speaks literally one line, which is “Pfft!”, but in context this still manages to express his bravery and bravado surprisingly well. On one hand, there is hardly any personal conflict or moments of life in these characters; on the other hand, that was still a pretty epic and exciting issue of a comic book, so it all kind of balances out.

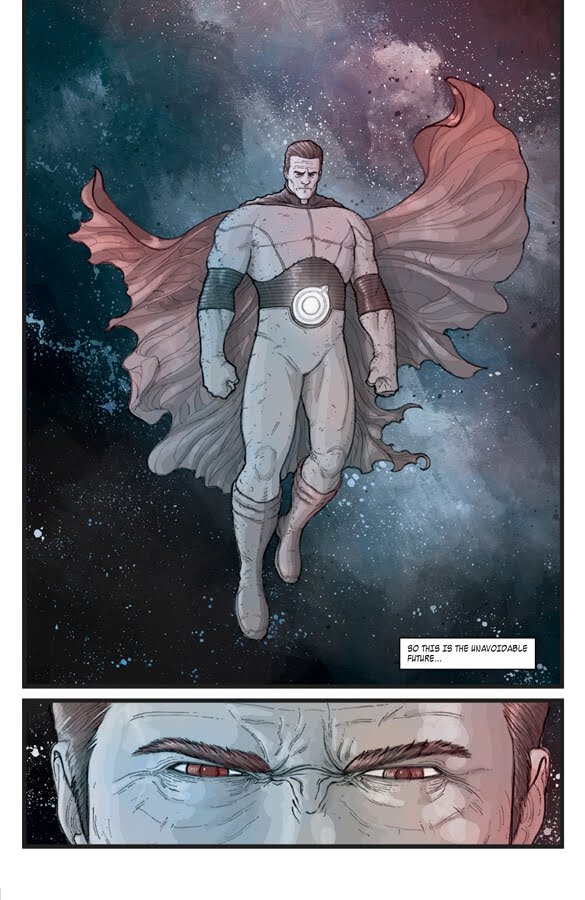

One could argue that it’s unfair to judge this story by a single issue, so let’s examine some of Hickman’s completed creator-owned work. Red Mass For Mars (art by Ryan Bodenheim) tells the story of an arrogant Superman-esque superhero named Mars who reluctantly returns from exile to save the Earth from an alien invasion. The cast is filled out by legions of visually compelling superheroes with interesting names, but we don’t really learn enough about any of them or their personalities to make them memorable (with the exception of the narrator). Through flashbacks, we learn the story of how Mars came to Earth as a child, and the circumstances surrounding his self-imposed exile—but these are plot points, rather than character moments. We’re given explicit details about the elaborate world of the story, and the action taking place; the people are just building blocks to serve those parts of the story. The narration that takes the lead and guides the story deals with brotherhood and the aspirations of a utopian civilization; the chapters are titled “Eternity,” “Liberty,” “Equality,” and “Fraternity,” respectively, which we are told is the “logical progression of perfect societal evolution.” But while these are interesting philosophical themes, they are not explicitly reflected in the plot or the characters. It’s almost as if we are being told a theme, which is then accompanied by dazzling, masterful worldbuilding, with everything else bringing up the rear. The main crux of the story seems to be Hickman’s grand philosophical treatise, along with Bodenheim’s incredible artwork; the plot and the characters are merely packing peanuts to help deliver this wondrous package to readers.

One could argue that it’s unfair to judge this story by a single issue, so let’s examine some of Hickman’s completed creator-owned work. Red Mass For Mars (art by Ryan Bodenheim) tells the story of an arrogant Superman-esque superhero named Mars who reluctantly returns from exile to save the Earth from an alien invasion. The cast is filled out by legions of visually compelling superheroes with interesting names, but we don’t really learn enough about any of them or their personalities to make them memorable (with the exception of the narrator). Through flashbacks, we learn the story of how Mars came to Earth as a child, and the circumstances surrounding his self-imposed exile—but these are plot points, rather than character moments. We’re given explicit details about the elaborate world of the story, and the action taking place; the people are just building blocks to serve those parts of the story. The narration that takes the lead and guides the story deals with brotherhood and the aspirations of a utopian civilization; the chapters are titled “Eternity,” “Liberty,” “Equality,” and “Fraternity,” respectively, which we are told is the “logical progression of perfect societal evolution.” But while these are interesting philosophical themes, they are not explicitly reflected in the plot or the characters. It’s almost as if we are being told a theme, which is then accompanied by dazzling, masterful worldbuilding, with everything else bringing up the rear. The main crux of the story seems to be Hickman’s grand philosophical treatise, along with Bodenheim’s incredible artwork; the plot and the characters are merely packing peanuts to help deliver this wondrous package to readers.

Jonathan Hickman’s debut book The Nightly News was a dizzying conspiracy story with layers upon layers of unreliable narrators, which made for an intoxicating read and established him as an inimitable literary voice. Even though his work sometimes tends to fly in the face of traditional storytelling values and clear, compelling dramatic arcs, this doesn’t necessarily mean that he is a problematic or poor storyteller. Rather, Jonathan Hickman takes a uniquely progressive approach to the art of narrative, and even though it may not be what we as readers are typically accustomed to, it’s challenging nature still deserves to be applauded.

Thom Dunn is a Boston-based writer, musician, homebrewer, and new media artist. He enjoys Oxford commas, metaphysics, and romantic clichés (especially when they involve robots). He firmly believes that Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believing” is the single worst atrocity committed against mankind. Find out more at thomdunn.net